This sentence probably best represents the attempts that the Vienna Circle made for metaphysics, knowledge, and epistemology in general. And what they meant by this sort of either obvious or cryptic sentence is that they were aiming to create a perfect language and a perfect knowledge that was based in reality just as much as the physics of their time was. (Or so they thought.) And if you couldn't speak about something that perfectly, well then don’t talk about it at all. It must be passed over in silence. Of course, they ended up failing in that pursuit. And philosophers often talk about all kinds of things that don't meet this criteria of perfect knowledge. You can see several of them here.

As they all went through this topic, they had the typical kinds of dogmatic, nihilistic, or relativistic presentations of what they thought the meaning of life was. Alice, in particular, speaking for Humanists UK, presented the view that everyone has their own meaning for life and we’re not against any of them. That can sound fine and non-threatening to outsiders, so I get why she speaks this way, but it spurred me to write something for our local humanist group in our monthly newsletter. I started with the idea from Dan Dennett's paper about Darwin's strange inversion of reasoning, and I said, “In exactly the same way, there is no singular, top-down ‘Meaning of Life’ that comes booming down to us from on high.” As much as we joke about 42 being the answer, something specific like that is just not going to be the solution. Instead, meanings are built up through trials and errors. But only some of these meanings lead towards more survival and flourishing for life on this planet.

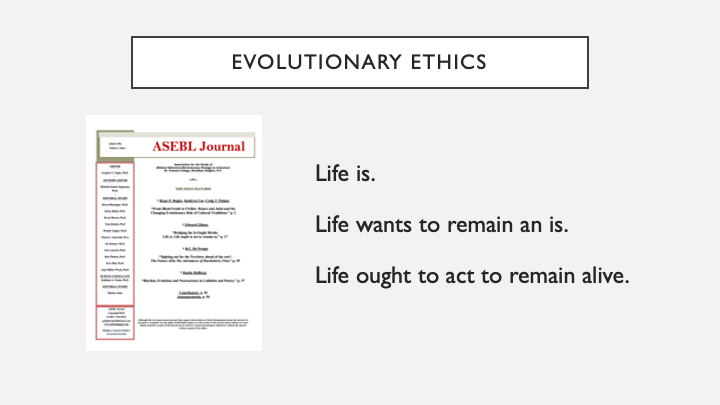

So, that's one simple way of looking at a concept in a gradualist manner and coming to a different kind of answer for how you might approach it rather than what is typically presented. And that last sentence in my approach is a reference to the evolutionary ethics that I've worked on, which is the next topic I'll talk about.

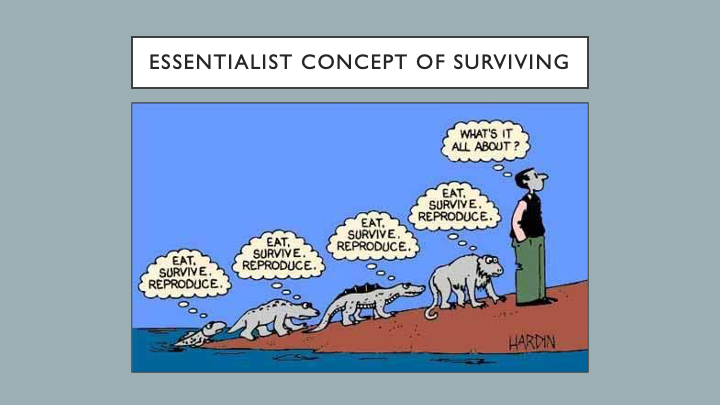

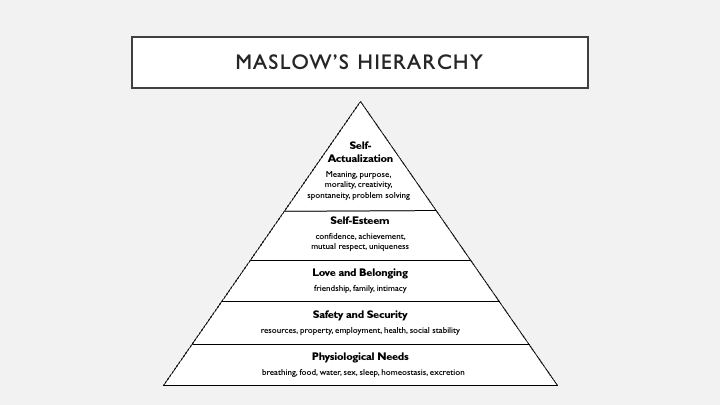

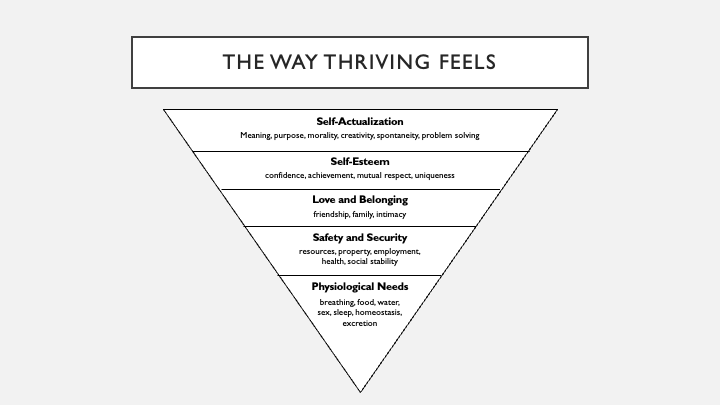

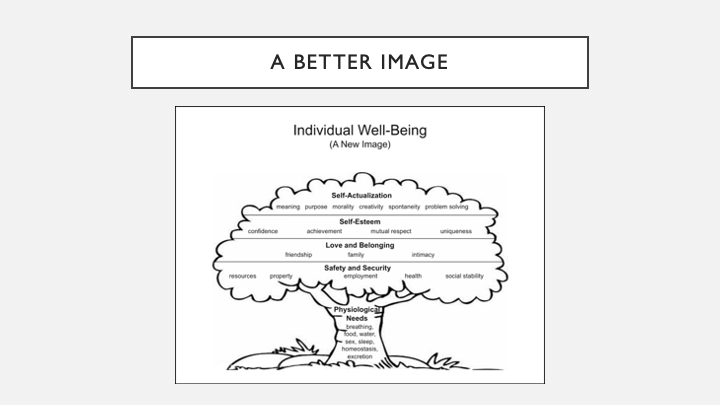

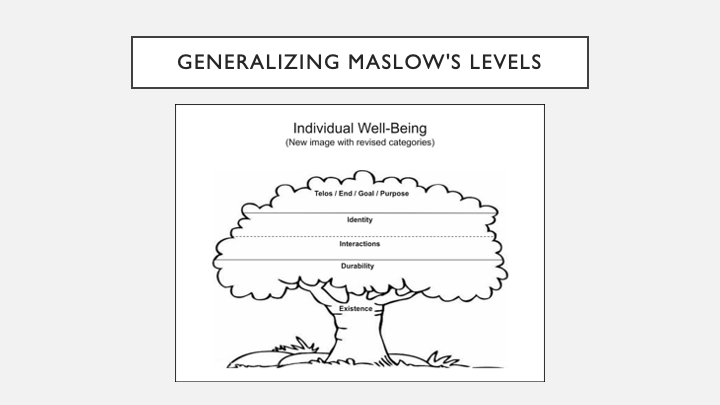

I got a lot of pushback on this article, as you would expect, but one of the common threads that is relevant for today was that a lot of people looked at this bottom line and said morals can't just be about remaining alive. That's too simple. It's got to be about much more than that. It's about well-being, and eudaimonia, and other highfalutin things. And to me, this was a classic example of having an essentialist concept of the word surviving.

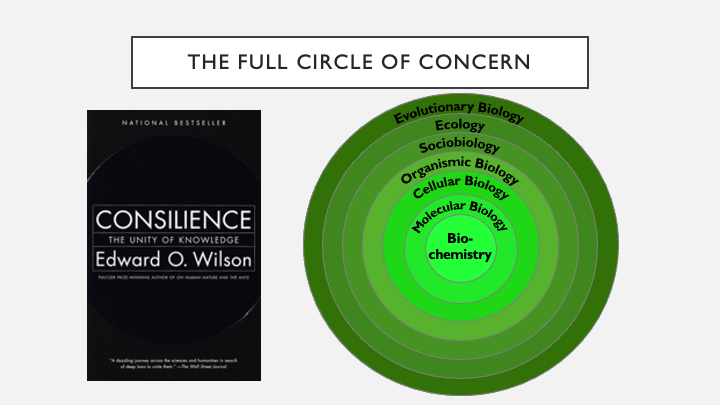

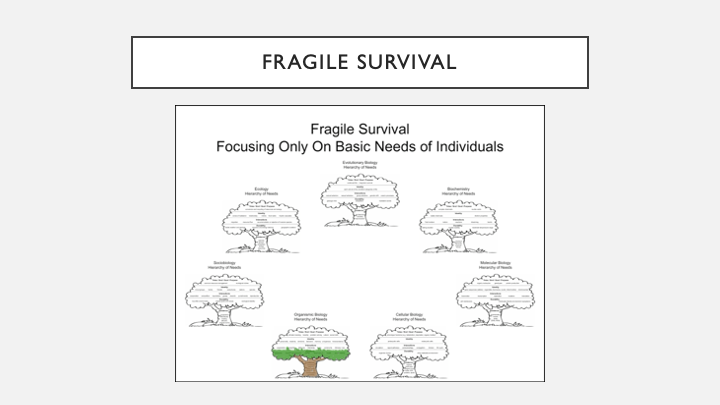

So, that is a nice way of looking at the gradualist view of survival. But it’s still only one slice of what we want to concern ourselves with. It's only considering the needs of individuals. And only human individuals at that too.

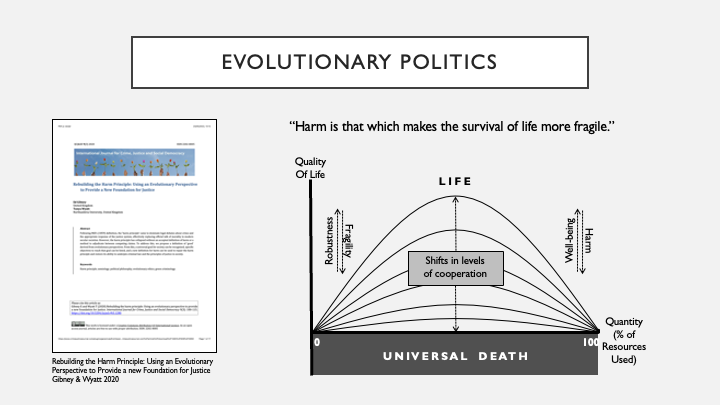

So, my wife and I wrote this paper to try and address this problem. The paper is called “Rebuilding the Harm Principle: Using an Evolutionary Perspective to Provide a New Foundation for Justice.” We took the definition of good that I had written in my previous paper, where good was about making the survival of life more and more robust, and we argued that harm is just going to be the opposite of that. Harm is that which makes the survival of life more fragile. Again, this is a topic for another day to get into all the details here. But once again this is another kind of gradualist view — in this case for harm — that helps us understand the problems that are involved in politics much better than some kind of essentialist definition of harm could ever hope to to provide.

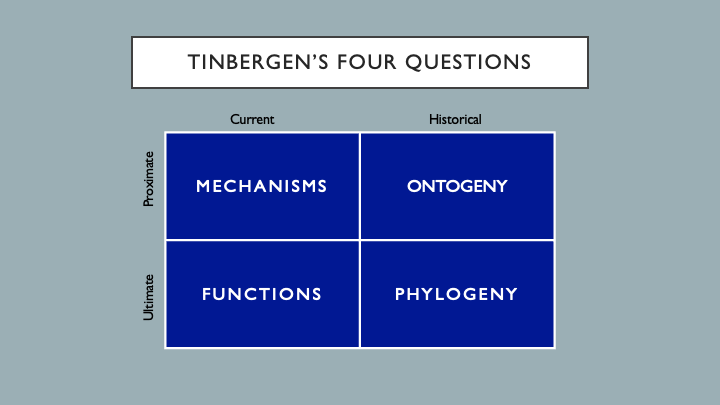

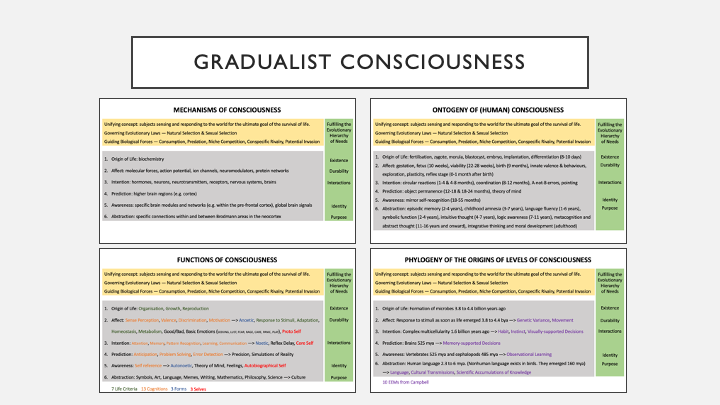

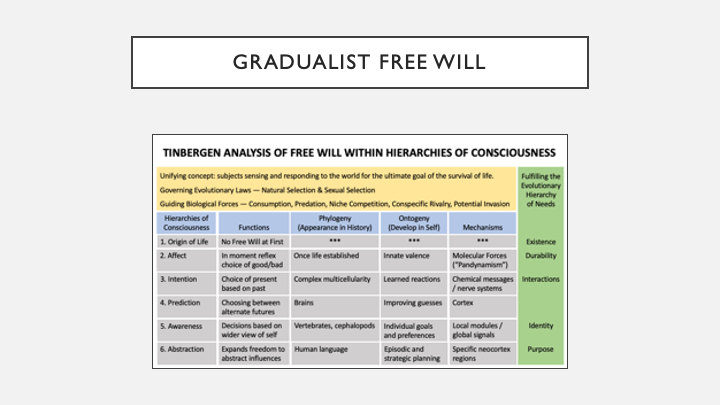

So, you end up with these four questions around ‘mechanisms’ (what are the underlying bits and bobs that are chugging away inside of the organism to cause something to happen); what is the evolutionary ‘function’ (what is the long-term purpose that will lead some things to happen); or you can look at the personal development of an entity (that's the ‘ontogeny’) so you know its singular life history; or you can look at the ‘phylogeny’, the evolutionary history that led up to that individual item. Again, to really understand anything in the biological world, you need to look at all four of these pieces. For any of you who have read or listened to David Sloan Wilson at length, this concept comes up pretty quickly. But there are very few philosophers that I've heard who ever talk about Tinbergen, even though philosophers talk about biological phenomena all the time!

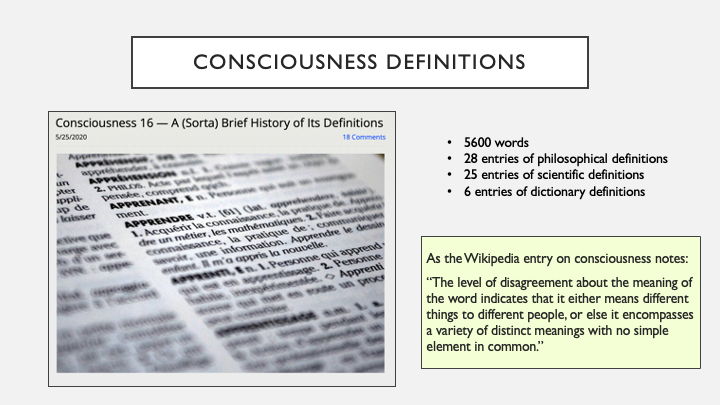

Almost all of these definitions were incompatible or disagreed with one another in some way. As the Wikipedia entry on consciousness notes, this level of disagreement about the meaning of the word indicates that it either means different things to different people, or else it encompasses a variety of distinct meanings with no simple element in common. Now, considering what we've been talking about today, it's clear that most of these definitions of consciousness have been looking for an essentialist, in-or-out box that just isn't going to be there. Consciousness is clearly another one of these complex phenomena in the biological world that is much better handled with a gradualist perspective on it (especially one that Tinbergen can give us).

And that's what I was able to do until all of these hierarchies aligned and ended up describing the emergence of all of the different properties that are generally considered within the various definitions of consciousness. Taken altogether, I believe they end up merging and presenting a multifaceted view of a gradualist approach to this extremely complex phenomenon.

Now, Dan holds his own very well against Gregg in my view. But he has never once referenced Tinbergen as far as I know. So, I used my review as an opportunity to introduce that concept into the discussion, which ended with that rhetorical question you can see at the end of this paragraph — is free will more like a geometry proof or a frog? To me, it's pretty obvious that it's more of a complex biological phenomenon like a frog, and it should therefore be treated as such like we've done with other Tinbergen analyses.

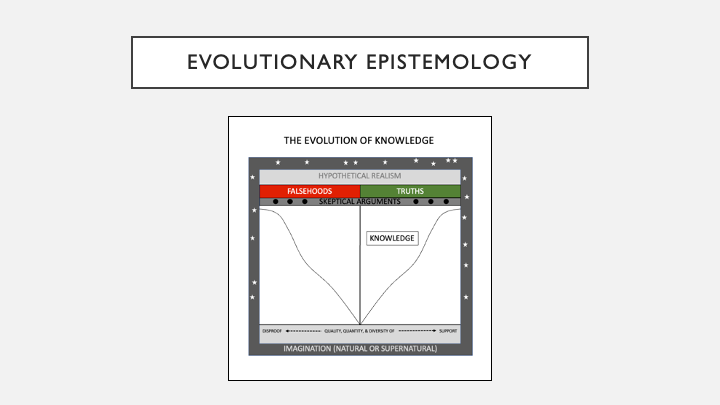

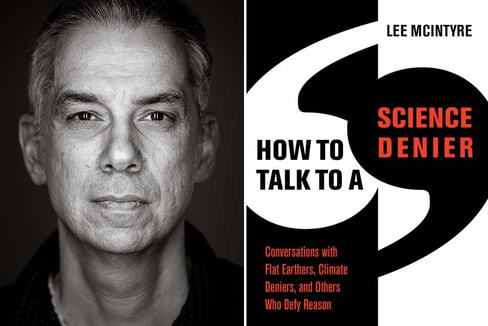

My contention in this paper will be that once again we need to start with Darwin’s strange inversion of reasoning and start at the bottom where we have absolute ignorance. Then, I’ll trace the evolutionary history of knowledge mechanisms as we have learned to learn, and developed new ways to learn, until we gradually built more and more robust knowledge. Even after all this evolution, we never quite reach the level of certain truths and falsehoods. We know this from some classic skeptical arguments, which show that we can't ever claim to know truth (so far) because we just can't know the future. Since we can't know what the future will bring, maybe the ideas we have today will some day be overturned. But that's okay! This sort of gradual, evolutionary understanding would give us a much clearer way to talk about knowledge and how strong it is or how fragile it is and why. And I think that conversation could do a lot to overturn all the nonsense we see about fake news and truthiness and the like. At least, that's my hope.