—Bertrand Russell, in A History of Western Philosophy (1945)

When discussing how Berkeley's philosophy appeared to be self-evidently false, but impossible to refute, Dr. Johnson kicked out at a nearby stone, exclaiming "I refute it thus!"

------------------------------------------------------

George Berkeley (1685-1753 CE) was an Anglo-Irish philosopher whose primary achievement was the advancement of a theory he called "immaterialism," later referred to as "subjective idealism" by others.

Survives

Needs to Adapt

Gone Extinct

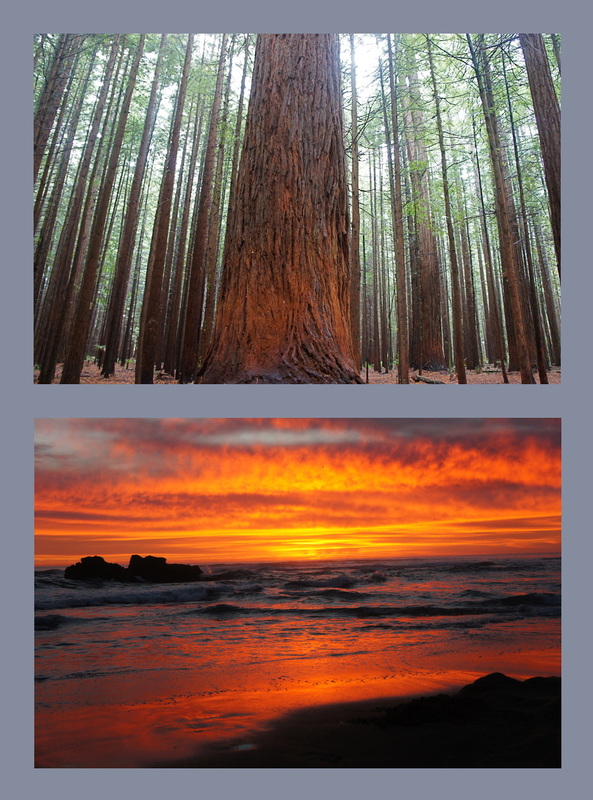

Berkeley’s theory of immaterialism contends that individuals can only know directly sensations and ideas of objects, not abstractions such as "matter.” The theory also contends that ideas are dependent upon being perceived by minds for their very existence, a belief that became immortalized in the dictum, Esse est percipi - to be is to be perceived. Over a century later Berkeley's thought experiment was summarized in a limerick by Ronald Knox and an anonymous reply: There was a young man who said "God / Must find it exceedingly odd / To think that the tree / Should continue to be / When there's no one about in the quad." // "Dear Sir: Your astonishment's odd; / I am always about in the quad. / And that's why the tree / Will continue to be / Since observed by, Yours faithfully, God.” Well that was fun. Abstractions such as matter are categories. They are definitions we can use to group actual objects together in order to study and understand them better. We created and defined the abstractions. They do not exist in the physical sense of the word, but we can know them for what they are. Also, the physical universe happily went on before us and wouldn’t care if we went extinct.

------------------------------------------------------