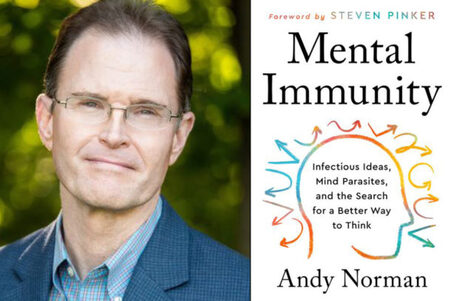

Back in January of 2022, I reviewed Andy’s book that introduced this idea — Mental Immunity: Infectious Ideas, Mind Parasites, and the Search for a Better Way to Think. I found it so interesting that I devoted two long blog posts to covering it. (See here and here.) I wasn’t alone in this interest either. Andy had many, many discussions about his book during the publicity tours he did for it, and he also organized a symposium in the online magazine This View of Life (now a part of ProSocial World) to gather thoughts about his book from a variety of philosophers and scientists. Andy and I agreed to invite all of these essay writers to discuss their thoughts with our Evolutionary Philosophy Circle, and that constituted our third generation of activity. After 14 weeks of deep readings and discussions, I put together a list of links and summaries for all of the essays we considered, which you can see below.

Please note that if you are interested in watching the recorded discussions that we had about these essays, you can find links for those by joining our Circle. Our fourth generation of activity will follow this format of organized essays and discussions around a general topic (this time featuring evolutionary ethics) so now’s a great time to join in for that! Anyway, on to the summaries for generation three:

Week 1

- Speaker — Andy Norman

- Article — The Science of Mental Immunity Has Arrived

- Summary — Minds have immune systems. Mounting evidence and novel arguments suggest this claim is quite literally true. Evolved systems have to defend themselves against internal and external threats. The body’s immune system is an evolved solution to this problem. Evolutionary theory predicts that comparable systems will be found at many different levels of selection. Look for such systems and you can find them at work protecting cells, organs, and bodies, nations, cultures, ideologies, religions, and minds. These entities have “immune systems” too. The mind’s immune system—its capacity to ward off problematic information—is implemented somehow in the brain. We can all benefit from “cognitive immunotherapies”: evidence-based interventions designed to boost and modulate mental immune response.

Week 2

- Speaker — David Sloan Wilson

- Article — Cultural Immune Systems as Parts of Cultural Superorganisms

- Summary — The concept of ‘organism’ must be expanded to include groups as organisms. When we do this, the concepts of both ‘mental’ and ‘immunity’ can be seen in a new light. Two key concepts for the purposes of this essay are multilevel selection (MLS) and major evolutionary transitions (MET). Today, every entity that biologists call an organism is regarded as a MET. From a multilevel perspective, the word “mental” cannot be restricted to individual cognition. Human moral systems make great sense from this perspective. Deviant behaviors are defined as cheating—a form of cancer—and punished. Foreign beliefs are tagged and removed, like infectious diseases. This does not distinguish fact from fiction. Instead, all beliefs and practices with fitness value (the survival and reproduction of the group) are distinguished from all beliefs and practices that pose a threat to fitness. Regardless of the past and present, there is an urgent need for a moral system that defines “us” as the whole earth, including the biosphere in addition to humans.

Week 3

- Speaker — David Samson

- Article — A Tribalism Vaccine

- Summary — In my book Our Tribal Future, I offer an operational definition of a tribe, which is: a meta-group – an intersubjective belief network – that uses symbols as tokens of identity signaling membership in a coalition. The ‘Tribe Drive’ leverages our species' capacity to create and transmit memes in a way that allows individuals, with no prior interaction, to see strangers as trustworthy. Religion, language, music, ritual, consumer behavior, clothing, and food can all emit such signals. Humanity had a new way to bootstrap cooperation, but the feature contained a bug. All humans today have inherited identity protective cognition — the tendency to unconsciously dismiss evidence that does not reflect the beliefs that predominate in our own groups. Tribalism is the belief that different identity-based coalitions possess distinct characteristics, abilities, or qualities, especially so as to distinguish them as inferior or superior to one another. To vaccinate the world from the tribalism virus, we need herd immunity of people who hold metabelief as their sacred value pegged to a single “community of inquiry” tribal identity. This is what I call a Metatribe. The syringe delivery system for the tribalism vaccine needs to leverage humanity's penchant for social norm creation and regulation to facilitate its spread. Historically, tribal creeds have served this purpose. What then, is an effective Metatribal creed for the long-awaited tribalism vaccine?

I am a member of Team Human.

Our creed is that beliefs can change in light of evidence.

We are a community of inquiry where beliefs are deemed reasonable if they can withstand reasonable challenges to their veracity.

We are the Metatribe.

Week 4

- Speaker — Ian Robertson

- Article — Mental Immunity, The Group Mind, and Existential Fear

- Summary — As a highly social species, humans have an evolved tendency to favor the ‘in-group.’ This trait significantly impacts our immunity, or lack of it, to false or harmful information. The emerging science of cognitive immunology must take full account of this fact. 'Minimal groups' have no purpose, past, or future. Real groups have a purpose – family protection, soccer team victory, religious dominance, or national prestige — they have long histories, rationales that usually involve trying to get a competitive advantage over other groups, and they have a strong sense of continuity into the future. Even in ‘minimal groups’ people allocate rewards to their ingroup and impose sanctions on the outgroup, even when the overall costs and benefits of their group-favoring choices are to everyone’s detriment! There appears to be a primitive drive in the human mind to define oneself in a group instantly and then automatically favor that group at the expense of an outgroup. Feeling bad about oneself makes people more tribal. It’s as if in compensation, the collective ego of the ingroup offers some protection. The fear of our extinction seems especially potent. One theory to explain this goes by the rather forbidding name of Terror Management Theory. The core idea of terror management theory is that we work hard to gain self-esteem and support for our worldview so as to ward off existential anxiety and that work pays off. It can be hard for millions of people to feel part of a group, but one surefire way of making that happen is to remind them of their mortality through fear and threat.

Week 5

- Speaker — Barry Mauer

- Article — Bad Ideas Recruit the Mind’s Immune System to Protect Themselves

- Summary — Some bad ideas get past a mind’s defenses and then hijack the mind’s immune system. This process is similar to what happens with metastatic cancer, which spreads from one location in the body to a distant one. Metastatic cancer “flips” elements of the body’s immune system, recruiting them to defend tumors and attack the body. When bad ideas hijack the mind’s immune system, these bad ideas become resistant to correction and the mind becomes susceptible to more bad ideas. Bad ideas spread in the mind and can eventually take it over. A pathological belief is one that “is likely to be false, to produce unnecessary harm, and to be held with conviction and tenacity in the face of overwhelming evidence that it is likely false and will produce unnecessary harm.” A group with a hijacked mental immune system is a cult; in a cult, the group’s mental immune system is altered to protect the group’s bad ideas at the expense of the group’s wellbeing, the wellbeing of its members, and of those around it. Institutions such as schools and journalism play outsized roles in enhancing or corrupting the mental immune systems of individual people and of groups.

Week 6

- Speaker — Steije Hofhuis

- Article — Witch-Hunting: A Lethal Cultural “Virus”?

- Summary — Historians are traditionally dismissive of comparisons between the evolution of living nature and history. History is thought to be far too complex and capricious to be captured in general principles. But what if we take the aforementioned comparisons seriously? Viruses are known to be extremely well adapted to reproduce within their environment. They make people cough and sneeze, for example, which enables them to infect others through the air. It appears like an intelligent design, but in fact, it was only a blind Darwinian process that did the manufacturing: variants that were accidentally adapted were cumulatively preserved in repeated rounds of selection. Biologists call this “design without a designer.” “The implementation of witchcraft persecutions spread contagiously, but any politically coordinated effort with that direct intent was conspicuously lacking.” It was a cultural design without a designer. The question of what function ideas such as the witches’ sabbath, flying witches, or child witches had for the people involved, or for their communities, does not necessarily bring us any further. For them, it was often harmful. But when we look at it from the reproductive angle of the witch-hunting phenomenon itself, all of it makes perfect functional sense. These cultural variants were ingeniously adapted to make this cultural “virus” spread.

Week 7

- Speaker — Ed Gibney

- Article — Evolving My View on Mental Immunity

- Summary — The actions of the so-called mental immune system may just be part of a larger, more generalizable function of the brain. When our minds swarm with doubts, it may be easier to think of this as problem-solving for our predictive worldview, rather than the actions of some kind of neuronal version of white blood cells. That way, the swarming of reinforcements that I personally experienced can also be explained by the same mechanism. This seems more parsimonious. Inoculation theorists have shown that exposure to weakened information threats will tend to “inoculate” a mind against more formidable versions of those same threats. But perhaps this isn’t inoculating a mind against bad ideas so much as scaffolding a worldview in another rigid direction. If I’m right, then mind inoculation will only work if it is received from a trusted source. Even if the weakened idea is a “bad” one, whenever we perceive the inoculation as coming from “them” then the inoculation should not work as intended. In fact, don’t we see this all the time with the sharing, belief, and disbelief of ideas among friends, foes, and relatives? Andy’s definition of mental immunology is, “The mind’s wherewithal for warding off bad ideas.” That’s just a very broad description of a wide-ranging function. We could easily adopt this and still say that the brain can perform this function using general mechanisms, even if there isn’t a specifically evolved mental immune system, like there is for bodily immune systems. If so, how can we highlight this metaphor’s similarities without brushing over the differences and leading people astray? Perhaps making a clear list of the differences between bodily immunity and cognitive immunity may actually help with getting past some resistance to this project.

Week 8

- Speaker — Steve Gilbert

- Article — Changing A Belief Means Changing How You Feel: The Role of Emotions in Cognitive Immunology

- Summary — Psychotherapists have long known, and science has now confirmed, that there is no thought without feeling. All thought is affect-laden and important personal beliefs very much so. Changing your mind does indeed mean changing how you feel, especially so for beliefs, which are more emotion-sensitive than knowledge. Thus, changing a salient belief, toxic or otherwise, is often too heavy a lift for reason alone. Feelings “may be experienced as internal evidence for beliefs which rivals the power of external evidence from the environment” and may be given more weight than reason and evidence. Feelings also guide attention. Donovan Schaefer discusses this in the context of cogency theory: “To say an argument is cogent doesn’t mean, exactly, that it’s true. It means it appeals, or it’s compelling.” So, what might this look like in practice? Client-centered therapy centers on active (i.e., reflective) listening, empathy, and clarification of content and affect. Cognitive therapy focuses on how thoughts and beliefs cause feelings and how modifying thoughts can change feeling-states. My subsequent career as a psychotherapist taught me that both approaches are more powerful when combined than either alone. This review of the role of emotion in belief suggests that debunking may be more effective if intervention begins with a relaxation exercise, followed by an empathic conversation centered on the person’s feelings about their beliefs, next an elicitation of commitment to the values of open-mindedness and evidentiary belief, and lastly a presentation of disconfirming evidence and reasoned argument. All too often, the cart is put before the horse.

Week 9

- Speaker — Melanie Trecek-King

- Article — Teach Skills, Not Facts

- Summary — Why are nearly all undergraduate students, regardless of major, required to take science? The obvious answer seemed to be to foster science literacy and critical thinking … but what does that mean? Science is so much more than a bunch of facts to memorize. It’s a process. It’s a way of learning about the world, of trying to get closer to the truth by subjecting explanations to testing and critically scrutinizing the evidence. It’s not just what we know; it’s how we know. Basically, science is good thinking. To equip students with the skills necessary to evaluate claims, I provide them with a toolkit, appropriately summarized by the acronym FLOATERS. This stands for Falsifiability, Logic, Objectivity, Alternative explanations, Tentative conclusions, Evidence, and Replicability. Another of the most important lessons for students is about the limits of perception and memory. We often fail to recognize that our perceptions are subjective and highly biased and that our memories are flawed and unreliable. After students have a better appreciation of how flawed their thinking can be and the importance of skepticism, we turn to information literacy. It’s important that students recognize the limits of their knowledge and learn how to be good consumers of information more broadly. Science literacy is about more than memorizing facts. Instead of teaching students what to think, a good science education teaches them how to think.

Week 10 — RESCHEDULED DUE TO ILLNESS

Week 11

- Speaker — Zafir Ivanov

- Article — Reframing Mental Immunity

- Summary — I think with a slight reframing of this idea we will have a more accurate diagnosis of susceptibility to infodemics, which can lead to better treatment outcomes. The immune system is a layered system of defence. The innate immune system includes physical barriers such as the skin and mucous membranes lining the digestive and respiratory tracts as well as an immediate nonspecific smothering response by defensive cells. Beyond the innate defences comes the adaptive or acquired immune system where antibodies are custom made to the invader. Mark Sheller proposed the behavioural immune system, in which aspects of our behaviour aids in the prevention of infection to the point where it makes sense to think of these behaviours as a first line of defence of the immune system. Karen Shanker and her colleagues realized that behaviours associated with avoiding and combating infection affects not just the individual but also the group. They suggested broadening the behavioural immune system to the inclusive behavioural immune system. I think this is what our response to threatening ideas is built on. I propose that we stop referring to the mind having an immune system of its own and instead reframe this as the mind's contribution to our overall immune system. With this slight reframing we can avoid talk of metaphor and focus on more accurately understanding our various responses to harmful information. I also have many concerns about inoculation theory and think this needs to be reframed as well. My main concern is that inoculation theory requires no modification to be weaponized. Instead, generalizable tools that work with almost all ideas are not custom-made vaccines to specific viral ideas, they are much more like broad-spectrum antivirals. I think our efforts are best focused on developing new and refining existing tools with reduced weaponizability as a design criterion. Tools that are simple with obvious benefits that are likely to gain wide acceptance. Tools such as the New Socratic Method, Reason’s Fulcrum, Scout Mindset, the Pro-Truth Pledge, and Intuitive Bayesian Reasoning all have an antiviral effect.

Week 12

- Speaker — Luke Johnson

- Article — Paradigms in the Cognitive Sciences

- Summary — In his seminal work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn developed a philosophy of science that has since influenced many an intellectual through the idiomatization of the phrase “paradigm shift.” In Chapter 2 of Structure, Kuhn introduces the criteria for something to serve as a paradigm: it must be “sufficiently unprecedented to attract an enduring group of adherents away from competing modes of scientific activity… [and] sufficiently open-ended to leave all sorts of problems for the redefined group of practitioners to resolve.” Counterinstances to existing paradigms are viewed as anomalies until sufficient evidence and “extraordinary research” lead to paradigm shifts as a result of new theories that account for these “anomalies.” Essentially invented by Andy Norman, PhD, a philosopher of science, Cognitive Immunology is most extensively articulated in his book, Mental Immunity. But is Cognitive Immunology a distinct field of science, and if so, how? Or is it a pre-paradigm school of thought? What crisis is cognitive immunology addressing and what paradigm or paradigms it is challenging? Science communicators, public health officials, and educators have struggled to address the crisis of misinformation with the application of existing science. Cognitive Immunology seems to be addressing the failure of other cognitive sciences to provide solutions to the ideological polarization, extremism, and culture war of our time. Only time will tell if cognitive immunology spurs a scientific revolution, to what degree it influences human progress, and how it fits into the history of science.

Week 13

- Speaker — Maarten Boudry

- Article — Are Some False Beliefs Good For You?

- Summary — We all entertain some false beliefs about the world and about ourselves. Being totally deluded about reality is probably a bad idea, but who could object against some “little follies”, a few judicious falsehoods to sugar-coat the harshness of reality? To phrase the discussion in cognitive immunology terms, we have to look for misbeliefs that are mutualists – a relationship in which the host benefits from the “intruder” – rather than parasites, which only harm their host. Once you’ve done the hard work and weighed the costs and benefits of different follies, it’s time to embrace the most salubrious ones. But of course, it doesn’t work like that. You can’t just flip a switch in your brain and decide to believe something. In order to find out which misbeliefs are beneficial and which are harmful, you have to investigate the attendant benefits and downsides. But once you’ve done that, you are no longer in a position to embrace your favorite misbelief, which means that you’re also unable to reap its advantages. Is there any way out of this paradox? For my part, I’m not so sure. Even if you don’t have any objections against untruthfulness per se, how can you foresee all of the consequences and ramifications of your false belief? Reality, as the writer Philip K. Dick argued, is that which, after you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away. At the end of the day, would you not prefer to know the truth, warts and all?

Week 14

- Speaker — Andy Norman

- Article — Do Minds Have Immune Systems?

- Summary — Do minds have immune systems? In this paper, we remove several obstacles to deciding this question in a rigorously scientific way. First, we show why the scientific community needs to take up the question. Then, we give the hypothesis a name: the Mental Immune Systems Thesis (or MIST) is the claim that minds do in fact have immune systems. It’s tempting to dismiss this claim as “mere metaphor” – and many do – but that stance turns out to be indefensible. It is at best a well-intentioned stopgap: one that postpones a pivotal reckoning. So how to settle the question? Above all, we need clarity about the meaning of “immune system.” To that end, we examine candidate definitions, nominate one, and show why it makes sense to embrace that definition. We then consider an evolutionary argument for MIST: mental immune systems, so defined, didn’t just evolve, they had to evolve – to protect minded creatures from informational threats. We then detail some of MIST’s testable implications and summarize the extant empirical evidence. Finally, we discuss the prospects of cognitive immunology, a research program that (1) posits mental immune systems and (2) proceeds to examine and explain how they work. MIST, we conclude, is a hypothesis that deserves serious scientific development.

Other Essays in the Mental Immunity Series on This View of Life

- The Analogy of/and Inoculation Theory to Mental Immunity by Josh Compton and Sander van der Linden

- The Many Faces of Cognitive Immunology by Stephan Lewandowsky

- Building Mental Immunity by Nele Strynckx

Post-Generation Comments and Questions

- Questions for the MIST by Ed Gibney

- Do minds have immune systems? The title question from Andy’s latest paper cannot be answered without more clarification of the MIST. In particular, a definition of the general abstract label “immune systems” needs to be settled upon, a definition of the particular abstract label of a “mental immune system” needs to be agreed upon, and definitions of the component parts of this system such as “mental inoculation”, “mental parasite”, and “mental vaccines” all need to be developed and confirmed. Until the clarification of each of these terms occurs, the answer remains “no” for each and every one of them because new scientific theories remain guilty until proven innocent. Once this philosophical work of defining terms is complete, there are still two options going forward. The first may be to say yes, all of these philosophical definitions are logically consistent and by definition it is obvious or demonstrable that they all exist. This would create a philosophical argument for looking at the world in a particular way using a particular set of words. The second and more difficult option is to define all of these terms in such a way that they create falsifiable and empirically verifiable predictions. This would create a scientific argument that only remains to be tested in order to either be accepted into consensus, refined, or rejected.