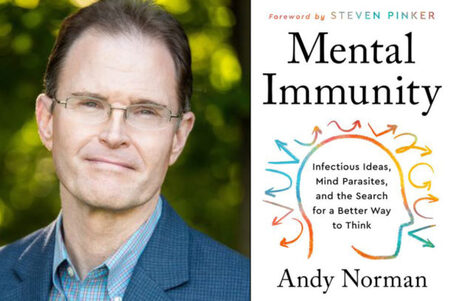

With all this in mind, I really need a few posts to cover Mental Immunity. There is already a ton of stuff out there for this book since Andy has done loads of publicity for it. The Media Appearances and Events page on his website lists almost 50 public discussions, including one with the granddaddy podcaster of them all, Joe Rogan! I haven’t listened to all of these discussions (sorry, Andy, I’m not a stalker), but from what I can tell by their summaries, they generally stay confined to roughly the first three-quarters of the book, since that covers what the title focuses on—cognitive immunology—and that is a new and important idea all on its own. Once that has been well and truly introduced, however, the final part of the book tries to solve some fundamental problems of epistemology by modifying a Socratic idea into something Andy calls a mind vaccine, which he proposes could improve the way we all think, and that would improve the lives of trillions of us and our descendants. Those are some big goals!

So, I’ll need another post to discuss that last part of Mental Immunity, but back in October, Andy was kind enough to fill in for a last-minute cancellation and give a talk to my North East Humanists group. That talk, like many of his other ones, stayed mostly confined to the cognitive immunology portion of the book, and I wrote a recap of that for our November bulletin. For this blog post, then, let me just repeat what I wrote there, lightly editing it for this outlet.

-------

As a fellow Humanist, Andy said we often think that a lack of ‘critical thinking’ is at the root of all the bad ideas out there today. Misinformation and disinformation are spreading like wildfire. An outlandish example is the QAnon conspiracy that the world is secretly being run by a cabal of paedophiles that can only be thwarted by Donald Trump. But bad information has serious consequences too. It has clearly impacted the 700,000 US and 140,000 UK Covid deaths, which could have been much fewer according to the performance of comparable countries.

There are many ideas for why this is happening—ignorance, gullibility, lack of critical thinking skills, polarisation, skilled disinformation, social media filter bubbles, and online search algorithms. What is missing from these explanations, however, is an empirical investigation of why some minds work well and don’t succumb to bad ideas. As Andy wrote in Psychology Today, Why Aren’t We All Conspiracy Theorists? Could we use this evidence to actually strengthen people’s minds? Such study has been called cognitive immunology, which can help us achieve mental immunity.

The formal history of this field began in the 1960’s with the psychologist William McGuire who studied the propaganda efforts of the Eastern Bloc’s military against the West. He noticed that minds act like immune systems. Weakened ideas can pre-inoculate a mind against stronger versions of harmful ideas. McGuire identified these ‘cognitive antibodies’ as part of what he developed into an ‘inoculation theory’. As is often the case with scientists trying to separate facts from values, this early work was quite amoral. McGuire simply studied how to guard against new ideas. But later researchers—e.g. John Cook, Sander van der Linden, Stephan Lewandowsky, and Josh Compton—have laid the groundwork for how to guard against bad ideas. And Andy Norman’s book Mental Immunity draws on his career in philosophy studying epistemology and ethics to expand on this greatly.

The way cognitive immunology describes it, bad ideas are a kind of mind parasite. Just like biological parasites, they require a host, they cause harm to that host, and they spread to other hosts. Minds also act like immune systems by spotting and removing these harmful ideas. And clearly, minds can function better or worse at the two tasks of filtering out bad ideas and letting in good ones. Minds cannot simply focus on one of those tasks; they must find the right balance between too much acceptance and too much rejection.

According to Andy, we can learn to enhance these cognitive immune functions. But the concept of ‘critical thinking’ isn’t enough. As an example, Andy told a joke about Fred the flat-Earther who dies and goes to heaven. (We’re all Humanists and don’t believe in any of this, but Andy said it’s just a joke so we can continue.) After his initial processing, Fred gets to stand in front of God and ask him one question. Fred asks whether the Earth is round or flat, to which God replies that it is indeed round. Fred’s response? “This conspiracy goes even higher than I thought!”

The point of this joke is that Fred the flat-Earther isn’t devoid of critical thinking skills. He’s actually thinking too critically. One of Andy’s friends, Lee McIntyre, has recently published a book titled How to Talk to a Science Denier in which he writes about going undercover to a flat-Earth convention. It turns out that the attendees there think we’re the ones who are gullible. They ask questions that we’ve never thought about. In many ways, they’re more critical than us. So simply saying “be more critical” can be bad advice. It can actually trigger a kind of autoimmune disorder which attacks perfectly good ideas. This is why mental immune health has become a much better concept to Andy than critical thinking skills, which he has taught for 20+ years.

It turns out that tens of millions of people are like Fred, warped by poor mental immune systems. They have been surrounded by bad cultural immune systems leaving them susceptible to bad ideas. How did this happen? One reason is that cultural sayings like “everyone is entitled to their own opinion” or “values are subjective” lead to poor mental immune functioning. These cultural ideas act as ‘disruptors’ to individual cognitive immune systems. And yet, they are extremely prevalent.

One question that often pops up for this subject is whether this is all just a metaphor. For Andy, the answer is a clear no. To him, this is real, and we are at the beginning of a scientific revolution that sees this. Andy has spent his career studying scientific revolutions and knows that they have signs, which we are beginning to see for cognitive immunology. The first microscopes allowed people to see microbes and that led to many scientific revolutions, including the understanding of our bodies’ immune systems, which saved millions and millions of lives. Cognitive immunology can do the same again and improve the lives of billions of people for generations to come.

As part of Andy’s work with his new research centre CIRCE (the Cognitive Immunology Research Collaborative), experts are coming together to develop this new science, learn how to map so-called infodemics, and then study how to disrupt them. CIRCE is trying to develop principles for cognitive hygiene that can help us all in the fight against bad ideas. Some early findings include the following:

- It’s easier to prevent poor thinking than to fix it. An ounce of ‘pre-bunking’ is worth pounds of cult deprogramming.

- Belonging to a ‘community of inquiry’ can help a lot. Typical communities include Humanists, scientists, or philosophers. Join in!

- Religions can often lead to closed minds since they encourage identifying with ideas that are set in stone and this triggers over-reactions of ‘identity protection’ whenever those ideas are questioned.

- It’s better to hitch your identity to the act of inquiry, rather than to any specific beliefs since those can always change with new information.

Andy finished his talk by asking us a question. As Humanists who are committed to thinking well and improving the well-being of others, what can we do to bring about the cognitive immunology revolution? How can we try to reduce the blight of bad ideas on all future generations?

(Editor’s note—sharing Andy’s talk or book is a good start!)

-------

There is a lot more worth reading in Mental Immunity, but that pretty much covers Parts I, II, and III. While I was preparing for this post, though, and listening to Andy’s appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience, something else occurred to me. So much of that discussion, just as it was for our North East Humanist discussion, was about how real mind-parasites and mental immunity are or whether these are just helpful analogies. It struck me that a Tinbergen analysis might actually prove helpful here. As a reminder, the pioneering ethologist Nicholaas Tinbergen said, “to achieve a complex understanding of a particular phenomenon, we may ask different questions which are mutually non-transferable. … What that phrase ‘mutually non-transferable’ really means in this case is your classic 2x2 matrix with 2 options for each of 2 different variables. … Setting up this 2x2 matrix yields the following four areas for consideration:

- Mechanism (causation). This gives mechanistic explanations for how an organism's structures currently work. (Static + Proximate)

- Ontogeny (development). This considers developmental explanations for changes in individuals, from their original DNA to their current form. (Dynamic + Proximate)

- Function (adaptation). This looks at a species trait and how it solves a reproductive or survival problem in the current environment. (Static + Ultimate)

- Phylogeny (evolution). This examines the entire history of the evolution of sequential changes in a species over many generations. (Dynamic + Ultimate)”

So, for mind parasites and mental immunity, I would say that Andy has three of these aspects covered. He can describe them from a functional perspective; he could trace the ontogeny of ideas within a single person’s life; and he could give the phylogenetic history of the ideas throughout our cultural history. But we simply don’t understand brains, neuroscience, or consciousness enough yet to (literally) flesh out the picture of mechanisms for these memes. This is a common problem for all studies of cultural evolution at the moment, however, and the rest of the picture is so compelling that it’s still worth using these evolutionary lenses to look at mind parasites and mental immunity as real things, rather than mere analogies.

What do you think? Is Andy on to something here? Does Mental Immunity help with the subtitle on its cover — the search for a better way to think? I think it definitely does and I’m looking forward to discussing that some more in my next post.