Photo from the Nobel Foundation archive.

Photo from the Nobel Foundation archive. Where should we look for such a framework? We could turn to Aristotle since his empirical studies of plants and animals led him to be considered the founder of the science of biology. During his observations and classifications, Aristotle developed a framework known as the four causes. And he said, “we do not have knowledge of a thing until we have grasped its why, that is to say, its cause.” The four kinds of causes are described briefly as:

- The efficient cause. This is something outside of the thing that is under consideration, which is responsible for the origination of that thing. For a table, this is a carpenter.

- The material cause. This is the material “out of which” a thing is composed. For a table, this might be wood.

- The formal cause. This is the form or shape of a thing which makes up the general definition of that thing. For a table, this could be its blueprint.

- The final cause. This is the goal or the purpose (telos in Greek) for which a thing originated and at which it aims. For a table, this could be dining.

These causes—arguably better translated as “explanations”—weren’t considered to be separable and mutually exclusive things that all operated on their own. Rather, they are just different aspects that work together to explain something in its full context. This line of thinking about biological organisms remained successful for about 2000 years. It was developed and used by Neoplatonists in antiquity, Averroes and Aquinas in the Middle Ages, and right on through to the 19th century. An elderly Charles Darwin even famously said, “Linnaeus and Cuvier have been my two gods, though in very different ways, but they were mere school-boys to old Aristotle.”

Looking at these four causes now, however, we see that Darwin undermined them completely. The four causes are static, they lack any sense of evolutionary history, and the final telos cause has been flipped upside down by Darwin’s “strange inversion of reasoning.” As the world got to grips with that, Julian Huxley (who was the grandson of “Darwin’s Bulldog” Thomas Huxley) gave us an updated evolutionary framework in his 1942 book Evolution: The Modern Synthesis. That looked at three major aspects of biological facts: 1) mechanistic-physiological, 2) adaptive-functional, and 3) evolutionary or historical aspects.

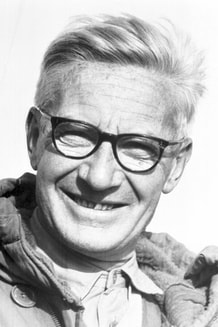

This is much better, but the final framework that evolutionary biologists still use today came a few decades later from Nicholaas Tinbergen. Tinbergen won a Nobel Prize in 1973 for his contributions as one of the founders of ethology (the study of animal behavior), and his 1963 paper “On aims and methods of Ethology” has “become a classic that gives evolutionary students of behavior a basic framework for their agenda. Tinbergen proposes, in what has subsequently become known as Tinbergen’s Four Questions, that to achieve a complex understanding of a particular phenomenon, we may ask different questions which are mutually non-transferable.”

What that phrase ‘mutually non-transferable’ really means in this case is your classic 2x2 matrix with 2 options for each of 2 different variables. In this case, Tinbergen considered static vs. dynamic views as well as proximate vs. ultimate views. The static view looks at the current form of an organism. The dynamic view looks at the historical sequence that led to it. The proximate view considers how an individual organism's structures function, whereas the ultimate view asks why a species evolved the structures that it has. Setting up this 2x2 matrix yields the following four areas for consideration:

- Mechanism (causation). This gives mechanistic explanations for how an organism's structures currently work. (Static + Proximate)

- Ontogeny (development). This considers developmental explanations for changes in individuals, from their original DNA to their current form. (Dynamic + Proximate)

- Function (adaptation). This looks at a species trait and how it solves a reproductive or survival problem in the current environment. (Static + Ultimate)

- Phylogeny (evolution). This examines the entire history of the evolution of sequential changes in a species over many generations. (Dynamic + Ultimate)

This framework adds the important consideration of ontogeny to Huxley’s three major aspects of biology. (How did he tell the story of a frog without the story of a tadpole?) The fact that Tinbergen arrived at four considerations is perhaps why “it has been repeatedly pointed out that this concept is derived from Aristotle’s Four Causes.” A paper called “Was Tinbergen an Aristotelian? Comparison of Tinbergen’s Four Whys and Aristotle’s Four Causes” thinks that “in general, they parallel very well” but honestly that feels a bit forced to me. (Try to match them up to see for yourself.) Tinbergen apparently never mentioned Huxley or Aristotle, but regardless of his inspiration, he now has the “standard framework in the behavioral sciences.”

If that’s the case, then why hasn’t consciousness already been considered using this framework? I was sure someone would have done this already, but I couldn’t find it. In fact, one of the top search results for “Tinbergen and Consciousness” was a paper called “The Mind-Evolution Problem: The Difficulty of Fitting Consciousness in an Evolutionary Framework” written by Yoram Gutfreund in 2018 in Frontiers in Psychology. I’ll say more about that later but let me quickly trace the history of this difficulty.

Firstly, Tinbergen wrote in the 1950’s and 1960’s at the height of the behaviorist movement in psychology which tried to get rid of cognitive studies. Perhaps because of this, Tinbergen himself thought his framework did not apply to consciousness. As he wrote, “Psychology does not come into contact with objective study of the lowest levels such as the reflex level, because introspection does not reach them. At the higher level, introspection brings us into contact with an aspect of behavior that is out of reach of objective study. … As scientists, we have to recognize the duality of our thinking and to accept it.” Duality?! Well I think I see a fatal flaw in his thinking about this.

Even Dan Dennett, however, apparently subscribed to this separation of consciousness from ethology. In his doctoral thesis “Content and Consciousness”, published in 1969, Dennett is described as saying that “in the intentional case the antecedent (intention) cannot be described or defined independently from the consequent (action), it [therefore] cannot be properly regarded in terms of cause and effect in the natural sciences’ sense; antecedent-consequent relationships in the behavioristic or ethological tradition (stimulus-response relationships) however can. These approaches are incompatible.” To untangle that jargon, Dennett meant that we couldn’t grasp our intentions as they arise and separate them into a standard model of cause and effect. I believe this is a problem we can solve now, but even the man who later called evolution a “universal acid” didn’t originally see how it could eat into this particular method of studying consciousness.

In fact, The Oxford Companion to Consciousness notes, “Conspicuously absent from [Tinbergen’s] ‘classical’ ethology were issues involving consciousness. Thus, in ethology as well as in behavioristic experimental and comparative psychology, questions of animal consciousness and related ones involving emotion and subjective experiences in general largely became taboo. To recognize a broadened view of ethology that encompassed cognitive, emotional, and conscious processes, Burghardt (1997) added a fifth aim, the study of private experience.”

When neuroscientists finally broke through these taboos in the 1980's and developed the field of Consciousness Studies, they kept some of this separation intact. As the founder of animal cognition studies Donald Griffin noted: “Crick and Koch (1998), leaders in the renewal of scientific studies of consciousness, take it for granted that monkeys are conscious. But they prefer to defer investigating nonhuman consciousness because they claim that ‘when one clearly understands, both in detail and in principle, what consciousness involves in humans, then will be the time to consider the problem of consciousness in much simpler animals.’” This might seem like prudent behavior, but I agree with Griffin who further said, “Restricting scientific investigation to the most complex of all known brains may be unwise, however, for insofar as consciousness can be identified and analyzed in a variety of animals, certain species might turn out to be especially suitable for investigating its basic attributes.”

Many neuroscientists have indeed studied the evolutionary origins of consciousness (see especially Feinberg and Mallat, and LeDoux), but not using Tinbergen as far as I can tell. In the paper I mentioned earlier about “The Difficulty of Fitting Consciousness in an Evolutionary Framework”, we can partly see why. The author Yoram Gutfreund noted that “the question of how the mind emerged in evolution (the mind-evolution problem) is tightly linked with the question of how the mind emerges from the brain (the mind-body problem). It seems that the evolution of consciousness cannot be resolved without first solving the ‘hard problem’. Until then, I argue that strong claims about the evolution of consciousness based on the evolution of cognition are premature and unfalsifiable.” But I already dismissed the worst of the hard problem in my post about it.

So, scientists remain unable, unwilling, or uninterested in tackling the philosophical problems of consciousness. They have also, in my view, drawn too small or too large a circle around the term to accurately describe it. What about philosophers? Can they attack these problems from their side?

In a lecture series from The Great Courses about Mind-Body Philosophy, the professor Patrick Grim of SUNY Stony Brook made a sketch of this in his final lecture titled “A Philosophical Science of Consciousness?” He proposed that we need an integration of philosophy, brain science, and AI in order to stand a better chance of grasping consciousness. He didn't have this new science worked out yet, but he offered: “a sketch of a speculative plan. First, figure out what consciousness is by figuring out what consciousness is for. What does it do that other cognitive processing could not? Second, analyze the process in abstract terms. What function is needed to produce the process we’ve identified as what consciousness is for? Then move to concrete specifics. How does the brain perform that function?” He finished by imagining that AI researchers could then build simulated brains using these discoveries and see where that got us in a kind of looped project with all sides informing one another for further progress. That iterative scientific process sounds great, but Grim entirely missed out on 2 of Tinbergen’s 4 questions. He only proposed we look at the 1st (mechanism) and 3rd (function) from my list above. He entirely ignored the 2nd (ontogeny) and 4th (phylogeny), which provides a striking example of the lack of evolutionary thinking among philosophers.

Well, let’s rectify that as best as I can. In my last post, I said consciousness involves living organisms, governed by the laws of natural and sexual selection, sensing and responding to biological forces. With that in mind, I think we can gain a lot of detail about this general definition by stepping through Tinbergen’s four questions one at a time. So, that’s what I’ll do with my next four posts. Please bear with me as I work on that for a while.

--------------------------------------------

Previous Posts in This Series:

Consciousness 1 — Introduction to the Series

Consciousness 2 — The Illusory Self and a Fundamental Mystery

Consciousness 3 — The Hard Problem

Consciousness 4 — Panpsychist Problems With Consciousness

Consciousness 5 — Is It Just An Illusion?

Consciousness 6 — Introducing an Evolutionary Perspective

Consciousness 7 — More On Evolution

Consciousness 8 — Neurophilosophy

Consciousness 9 — Global Neuronal Workspace Theory

Consciousness 10 — Mind + Self

Consciousness 11 — Neurobiological Naturalism

Consciousness 12 — The Deep History of Ourselves

Consciousness 13 — (Rethinking) The Attention Schema

Consciousness 14 — Integrated Information Theory

Consciousness 15 — What is a Theory?

Consciousness 16 — A (sorta) Brief History of Its Definitions

Consciousness 17 — From Physics to Chemistry to Biology