In 2009, the largest-ever survey of what philosophers actually believe was conducted by David Bourget and David Chalmers. On the question of which ethical system they subscribed to, respondents were given the three traditional choices of: 1) deontology (a rule-based system); 2) consequentialism (ends matter, best exemplified by utilitarianism), or 3) virtue ethics (morals are guided by some competing list of character virtues). How did they answer?

32.3% other

25.8% deontology

23.6% consequentialism

18.1% virtue ethics

So on perhaps the most important question in philosophy—how do you know what is right and what is wrong?—a plurality of expert philosophers look at the best choices they've developed, throw their hands up in the air, and say "none of the above." Derek Parfit (the man who inspired this week's thought experiment) shed quite a bit of light on this by making his survey answers public. He wrote in the comments for this question, "I believe that these main systematic theories all need to be revised, in ways that would bring them together."

Seeing holes everywhere, Parfit set out to poke them and expose them to even more daylight. If you aren't religious or a moral skeptic/relativist/nihilist, then the most common ethical position I've seen from philosophers is some kind of synthesis which says human well-being or flourishing (or eudaimonia from Aristotle's Ancient Greek) is the highest virtue, which yields a sort of utilitarian/deontological rule that what matters is the aggregate happiness, i.e. the happiness of everyone and not the happiness of any particular person, as long as no real deal-breakers are done to individuals. But Parfit saw that this kind of moral definition leads to a very problematic question: Where exactly are the limits of "aggregate happiness" in the face of a changing population?

To fully expose this problem, Parfit first had to show that populations will indeed change, but our moral concerns are independent of the hypothetical future people that are produced. (Note how reader Stephen Willey also illustrated this need with his insightful comment to the introduction of this week's thought experiment.) Parfit showed this independence with his introduction of the nonidentity problem. This is a huge problem deserving of its own post someday, but I'll just quickly introduce one example from it and how it led Parfit to his Repugnant Conclusion, which is the real ending point of the current discussion.

Parfit started down this path by considering how we ought to act in scenarios where our decisions will clearly change who will exist in the future. He looked at the following two possibilities:

- A pregnant mother suffers from an illness which, unless she undergoes a simple treatment, will cause her child to suffer a permanent handicap. If she receives the treatment and is cured her child will be perfectly normal.

- A woman suffers from an illness which means that, if she gets pregnant now, her child will suffer from a permanent handicap. If she postpones her pregnancy a few months until she has recovered, her child will be perfectly normal.

What should the women do in either of these two cases? In the first instance, our best predictions say the mother ought to get the treatment since her *actual* child will be more likely to have a better life. We can't say exactly the same thing for the second scenario though. In that case, when the woman delays her pregnancy, a different child will be brought into existence. The original potential child with the permanent handicap is rendered nonexistent by her choice, so to claim the mother ought to postpone her pregnancy is to say nonexistence is better for that person than an existence with a handicap. But that's not an argument anyone wants to make.

What this shows is that the benefits or harms done to future people must be independent of who those actual people turn out to be. Parfit calls this the “No-Difference View”, meaning it makes no difference who that future person is, the woman in the second scenario ought to postpone her pregnancy, just like the woman in the first scenario ought to undergo the treatment. This line of thinking, then, leads directly to what Parfit calls "the Impersonal Total Principle: If other things are equal, the best outcome is the one in which there would be the greatest quantity of whatever makes life worth living." In doing this, Parfit has managed to decouple benefits and harms from actual people and allowed these plusses and minuses to be considered from an impersonal perspective of the universe. This leads to some dark places though, since it implies that any loss in the quality of lives in a population can be compensated for by a sufficient gain in the quantity of a population. This is precisely the starting point laid out in this week's thought experiment. Let's finally take a look at it now.

---------------------------------------------------

Carol had decided to use a large slice of her substantial wealth to improve life in an impoverished village in southern Tanzania. However, since she had reservations about birth-control programmes, the development agency which she was working with had to come up with two possible plans.

The first would involve no birth-control element. This would probably see the population of the village rise from 100 to 150 and the quality of life index, which measures subjective as well as objective factors, rise modestly from an average of 2.4 to 3.2.

The second plan did include a non-coercive birth-control programme. This would see the population remain stable at 100, but the average quality of life would rise to 4.0.

Given that only those with a quality of life ranked as 1.0 or lower consider their lives not to be worth living at all, the first plan would lead to there being more worthwhile lives than the second, whereas the second would result in fewer lives, but ones which were even more fulfilled. Which plan would make the best use of Carol's money?

Source: Part four of Reasons and Persons by Derek Parfit, 1984.

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 154.

---------------------------------------------------

While Carol's singular dilemma is mildly interesting (and I will address it before the end of this post), this is really just the opening salvo that leads eventually to Parfit's Repugnant Conclusion. As it was originally written, that conclusion looks like this:

“For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living.”

In other words, Carol's immediate problem is just a minor tradeoff. If we do the math (as reader John Johnson noted in his comment to this thought experiment), the "total happiness" of 3.2 x 150 = 480, which is greater than 4.0 x 100 = 400, and much greater than the current state of 2.4 * 100 = 240. Judging by total happiness, as you should according to the conclusion of Parfit's Impersonal Total Principle, you get a clear choice. But eventually, if you keep scaling this up, you might reach 500 people with a quality of life of 1.01, barely above having a life worth living, and that would somehow outweigh any of the current scenarios. Scaling this up to the size of the Earth, any morality that favours 100 billion nearly-suicidal people is indeed a repugnant morality. But how to avoid it?

The Repugnant Conclusion "highlights a problem in an area of ethics which has become known as population ethics" and "the last three decades have witnessed an increasing philosophical interest in" such questions. Shockingly, "it has been surprisingly difficult to find a theory that avoids the Repugnant Conclusion without implying other equally counterintuitive conclusions." Parfit "finds the Repugnant Conclusion unacceptable and many philosophers agree." The problem, however, is "to find an adequate theory about the moral value of states of affairs where the number of people, the quality of their lives, and their identities may vary." Parfit sought what he called a Theory X, which would be able to solve the nonidentity problem without leading to the repugnant conclusion, but by Parfit's own conclusion, "he had not succeeded in developing such a theory."

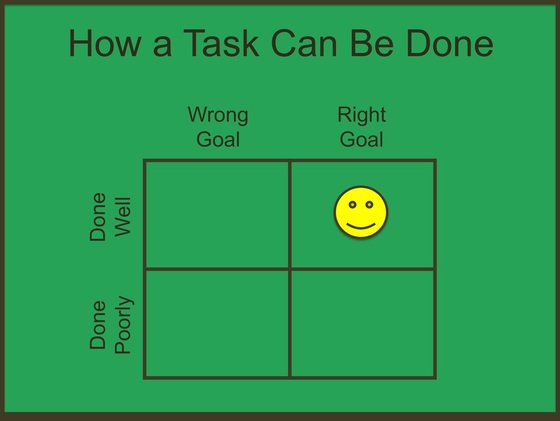

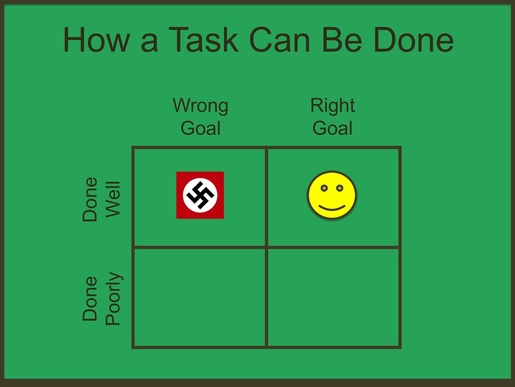

I believe my own moral theory does solve these problems, but before I get to that, for the sake of rigour, let's quickly run through the Eight Ways of Dealing with the Repugnant Conclusion, according to current academically published attempts (with the problems they incur summarised in parentheses):

1. Introduce new ways of aggregating welfare into a measure of value:

1.1 E.g. use the average principle. (This leads to a repugnant conclusion in the opposite direction.)

1.2 E.g. use variable value principles. (This is like the economic concept of utility, but it is not grounded in anything objective so different variables lead to different outcomes, making this solution useless.)

1.3 E.g. use "critical level" principles. (Okay, but what is critical? Baggini's 1.0? No one can say.)

2. Question the way we can compare and measure welfare. (Well-being isn't a single smooth variable. This is true, but it doesn't offer us any way to judge population ethics.)

3. Count welfare differently depending on temporal or modal features. (I.e., if the same exact people are worse off in one scenario vs. another, then you can judge. Otherwise, you can't really make a comparison. This may be true, but again, it doesn't help us.)

4. Revise the notion of a life worth living. (This objection doesn't believe lives can be positive or worth living, which is counterintuitive to say the least, and leads to repugnant conclusions in the negative direction.)

5. Reject transitivity. (This unacceptably radical proposal says p>q, and q>r, but r>p, which requires an upheaval of all logic. It also doesn't provide any answers.)

6. Appeal to other values. (Offers to use "maximin" (the well-being of the worst off) or egalitarianism (all must be equal) as the final judge. But, again, these lead to repugnant conclusions in the opposite direction.)

7. Accept the impossibility of a satisfactory population ethics. (In other words, there is no Theory X without changing some of the assumptions. But no one has said how this change might be done.)

8. Accept the Repugnant Conclusion. (We are deluded by our intuitions so repugnance doesn't mean the densely-populated-barely-satisfied outcome is wrong. Ugh!)

To me, this list is absolutely mind boggling. How can the entirety of discussions about population ethics completely neglect any biological and ecological considerations of population studies? Not one philosopher is willing to look at the busts following booms of animal populations and say we ought not go there? Seriously, how removed from reality are philosophers?? But this is what happens when a field considers the naturalistic fallacy some kind of electrified third rail one dares not approach and the is-ought divide as an unbridgeable chasm. Philosophers have refused to look at what is to help tell us what ought to be. Fortunately, this isn't a problem for me.

According to my evolutionary ethics, our moral oughts are derived from natural desires to remain alive. Oughts follow from wants, which are based on what is. Of course, we can't just follow any old want. We evolved from the tiniest of organisms with the narrowest views of what is in the world, so we still feel competing wants up and down the entire spectrum of possibilities. If we want a truly universal and objective morality though, we have to listen to a universal and objective want—the need for "life in general" to survive over an evolutionarily long timespan. This is one of my main tenets: a universal definition of good arises from nature. Good is that which enables the long-term survival of life.

As I regularly note, E.O. Wilson gave us a total and consilient view of "life in general." Biology is literally "the study of life" and so all the biological sciences strung together give us a complete picture of life that looks like this:

(1) Biochemistry → (2) molecular biology → (3) cellular biology → (4) organismic biology → (5) sociobiology → (6) ecology → (7) evolutionary biology.

So, when Derek Parfit starts with his premise of the nonidentity problem, which says good is independent of specific future individuals, I say, of course. The good of specific individuals is only relevant within the narrow level 4 picture of organismic biology. When Parfit goes on to calculate his moral math using only the totals of individual and collective well-being, he has expanded the purview of his considerations to levels 4 and 5, but as he reaches his repugnant conclusion, he doesn't understand why. Why would 100 billion humans be miserable on Earth? Precisely because they would be butting up against real constraints in the 6th and 7th levels of life—the ecological constraints that impact the continued evolution of a species. Without taking that into consideration, Parfit's morality is too small. And this, apparently, is true of all other philosophers as well. This is what stops them from seeing the way out of the dilemma they are boxed inside of.

To really drive home just how boxed in philosophers' thinking is on this, let me quote again from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on the Repugnant Conclusion. The author there states:

It might be tempting for people who have little sympathy with utilitarian thought to try to set the problems raised by the Repugnant Conclusion to one side, thinking that it constitutes a problem only for utilitarians. However, most people tend to believe that we have some obligation to make the world a better place, at least if we can do so without violating any deontological constraints, and at a not too high cost to ourselves. Clearly all who think along these lines, even without being utilitarians, are faced with the problem of the Repugnant Conclusion. We can assume that other values and considerations are not decisive for the choice between populations....[so the] Repugnant Conclusion is a problem for all moral theories which hold that welfare at least matters when all other things are equal. (my emphasis added)

This is the wrong assumption! Welfare, well-being, flourishing, eudaimonia...whatever you want to call it...it does matter, but it is NOT paramount. Survival is paramount, and therefore decisive. You can have all the thriving you want, but only AFTER your morals point life towards survival. If well-being were the ultimate and decisive value, whose well-being would be worth marching everything else to extinction? When an issue A supervenes upon issue B, issue B is more fundamental. The issue A of well-being can only be satisfied if the issue B of existence is met. Survival / existence is the most fundamental attribute we must build our morality upon. So let's turn now to see how I do that.

To restate the original problem, Parfit said it was "to find an adequate theory about the moral value of states of affairs where the number of people, the quality of their lives, and their identities may vary." To answer this all at once in summary, my theory states that identities may vary, and both the number of people and the quality of their lives ought to exist within some range that balances scientific progress against existential robustness. What do I mean by that? Here are some details to flesh out the picture.

In my journal article, I wrote:

We can learn from...what has worked in the past to generalize about how we as a species must move forward into the future. What traits do we currently believe will lead to survival over the long term? Suitability to an environment. Adaptability to changes in the environment. Diversity to handle fluctuations. Cooperation to optimize resources and reduce the harm that comes from conflict. Competition to spur effort and progress. Limits to competition to give losers a chance to cooperate on the next iteration. Progress in learning, to understand and predict actions in the universe. Progress in technology, to give options for directing outcomes where we want them to go. These are the virtues and outcomes we must cultivate to face our existential threats and remain determined to conquer them.

This view of diversity, adaptability, suitability, and cooperation is part of what I mean when I said "identities may vary." Starting with my view that morality is best understood from a universal and objective perspective, I therefore not only agree with Parfit's precondition that identities may vary, but I also go further by saying that they should vary.

So, we can now move on to the more difficult bracketing of quantity and quality of lives. What are the minimums and maximums that frame this debate? If we are going to talk about numbers and types of lives, first we must give an answer to one of the very biggest philosophical questions—what is the meaning of life? I recently finished an excellent book by philosopher John Messerly on this topic called The Meaning of Life: Religious, Philosophical, Transhumanist, and Scientific Perspectives. It is an excellent summary of the best modern answers to this question from all the major philosophical positions. In the book, Messerly notes that none of these positions have generated an accepted viewpoint yet, but his analysis along the way caused me to generate my own thoughts on the question, which I shared with him in a private exchange. I wrote:

When asking the question, “what is the meaning of life?”, a fundamental clarifying question must be “for whom?”. Wants and meaning must be applied to someone. The "universe" doesn't want anything, and nothing is meaningful to it. This is why searches for "ultimate meanings" are senseless. They look for emotionally-led oughts where there can be no emotion. But life does want. So life ought to live. (See my ASEBL Journal article.) The scope of the universe is too large for one human life to have an impactful meaning upon it. Our imagination scales infinitely though, so we can imagine that we could. The story of life in general, however, is big enough to have meaning in the universe. And our role in the story of life could actually be quite large. Even if individually a life were not very important, we've evolved to feel pleasure at the scale we can affect life, so our lives can still feel quite meaningful when we accept the size of the role we've inherited. We don’t long for the role of a stellar nursery giving birth to stars, nor are we satisfied with the accomplishments of a mayfly. The 'big freeze' or the 'big crunch' are still possibilities for universal death within this universe, which would render everything meaningless, but maybe those outcomes can one day be affected by life within this universe. Maybe dark energy, dark matter, or something else altogether unknown can be manipulated in such a way as to balance things for survival. Until we can do that, that is a goal which gives meaning to life. We may not be able to answer any ultimate questions now of why the universe and life exist, but maybe someone will be able to someday. It is our job to do what we can to get to that. Survival and scientific progress are prerequisites along that path. Just as Renaissance people (to take one example) could be said to have found meaning in supporting a society that lead to the growth of the scientific method, which helped us get this far, we can find meaning today by doing our job to support a society laying the groundwork for future knowledge explorers too.

Messerly turned this into a blog post on his wonderful site Reason and Meaning, where he quoted my response as "from an astute reader," and then said:

I think the reader has it about right. The only way our individual lives have objective meaning is if they are part of something larger. We hope then that we are links in a golden chain leading onward and upward toward higher levels of being and consciousness. The effort we exert as we travel this path provides the meaning to our lives as we live them. And if our descendents, in whatever form they take, live more meaningful lives as a result of our efforts, then we will have been successful.

So this is what I mean when I said in my journal article that we need "Progress in learning, to understand and predict actions in the universe. Progress in technology, to give options for directing outcomes where we want them to go." In Matt Ridley's bullishly optimistic TED Talk "When Ideas Have Sex", Ridley pointed out how science has continued to solve major problems that chicken littles have been worrying about for decades. His perspective is leading the charge of the futurist technocrats who believe that more people leads to more ideas, which leads to more solutions to our problems. But as Aldo Leopold pointed out decades earlier, just because we have seen some increase in benefits due to early increases in population density, this does not prove that all further increases in density will lead to further increases in benefits. In fact, we have seen quite the opposite when numerous populations in the past have outgrown the ecology that supports them. At some point, "mere-additions" (another name for the Repugnant Conclusion) will bring species to a tipping point that push the whole population from "robustness" into "fragility" as Nassim Taleb described in The Black Swan.** In other words, I believe there is a curve for population quantity and quality where having too few people, or living in societies too repressive for science to flourish, causes a stagnation in the growth of technology that we need to stave off mass extinctions from asteroids, exploding suns, and collapsing universes. On the other side of that curve, we can have too many people so as to cause our own mass extinction—to be the potato bug who exterminated the potato and then itself, as Aldo Leopold said in his 1924 essay, “The River of the Mother God.”

In my moral theory, therefore, the numbers of people and the quality of their lives ought to remain in some range between the constraints I've outlined in order for the population as a whole to move towards a positive moral outcome. Do we know exactly how the size of that range is defined? No. Although we've barely begun to ask the right questions to find it. Going back to my journal article though, I addressed this uncertainty when I wrote:

The probabilistic nature of knowledge means we won’t always know how to solve our moral conflicts – in fact, we may never be certain of some of the answers either before or after we make a decision. How do we proceed then where we don’t know? Carefully of course, and taking a cue from The Black Swan, which made a study of this fuzzy realm where consequences of improbable events may be large and especially terrible. Limited trial and error is the way life has blindly found its way through these dark minefields of existence in the past, and anyone that takes a big bet on a non-diversified strategy will eventually lose everything over the billions of repetitions that our existence in evolutionary timescales allows. So even if we become confident about the direction we would like to go, humans should not be lured into racing there using existentially risky behavior.

Based on the best available science, we are not heeding that final warning. We do not seem to be in danger of having too few people or too little scientific progress to worry about existential stagnation. Quite the contrary. In a recent piece that I wrote for theHumanist.com, titled The Call of the Rewild, I wrote:

We may be in the middle of a sixth large extinction event, which prompted environmental scientists in 2009 to list biodiversity loss as one of the nine “planetary boundaries” that should be monitored for an overall picture of ecological stability. While it’s true there have been minor fluctuations in the environment since the last Ice Age, the relative stability during our current era compared to the rest of geologic history is what has allowed agriculture to develop and form the foundation of our complex and modern societies. Scientists believe that crossing one or more of the nine planetary boundaries may be globally disastrous due to the risk of triggering the kind of geologically sudden environmental change that most biological organisms cannot adapt to quickly enough to survive over the long term.

Frighteningly, we have already crossed three of the nine planetary boundaries and may only believe we’re okay because of the short-term focus of our evolutionary vision. In addition to crossing the prescribed boundaries for carbon in the atmosphere, and for nitrogen extracted from the atmosphere, we have also crossed the boundary for biodiversity loss. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, the extinction rate of species lost per million of total species-years (E/MSY) has been estimated to be between 0.1 and 1. Scientists setting the criterion for this planetary boundary decided the “safe” limit of extinction was 10 E/MSY, but currently, driven by human activity, the value is over 100. In other words, the current rate of extinctions on this planet is 100 to 1,000 times greater than it was before humans evolved, and that’s over ten times worse than what our best estimates think the planet’s currently supportive ecosystems can handle. This needs to change.

Probably the biggest thing holding us back from making this change is bad philosophy. As we can see in this week's thought experiment, our best thinkers have no good ethical systems, and as a result of this they have remained stuck arguing about individual vs. social consequences for so long that they haven't been able to give the rest of society a framework to notice that we're about to render all those smaller problems moot by acting immorally with respect to ecological and evolutionary concerns about life.

Back at the beginning of this long post, I noted how Derek Parfit said, "I believe that these main systematic [ethical] theories all need to be revised, in ways that would bring them together." The moral system I have outlined above, revises and brings all of the others together. It is based upon a deontological rule — "good is that which enables the long-term survival of life" — and it gives us an objective and universal consequence towards which we ought to act using virtues derived from evolutionary studies that scientifically prove to us which traits are successful in leading life towards that goal.

So, to wrap the discussion of this thought experiment up completely, the rich philanthropist Carol ought to drop her mathematical questions about individual vs. social well-being, and teach the impoverished village about birth control if she really wants to help. On second thought, it sounds like she ought to forget about the tiny village in Tanzania altogether since they probably already know more than she does about ecological constraints on their lives. She, and the rest of us who know better, ought to spread that moral message to the rest of the modern world, which is in such great peril.

--------------------------------------------------------

** I love the paperback edition of The Black Swan so much, with its addition titled "On Robustness and Fragility," that I'd like to quote a few of its passages at length here. Check these out, and then consider reading the whole book.

p.347:

Before The Black Swan, most of epistemology and decision theory was, to an actor in the real world, jut sterile mind games and foreplay. Almost all the history of thought is about what we know, or think we know. The Black Swan is the very first attempt (that I know of) in the history of thought to provide a map of where we get hurt by what we don't know, to set systematic limits to the fragility of knowledge—and to provide exact locations where these maps no longer work.

pp.370-373:

We can subscribe to the following rules of wisdom to increase robustness:

1. Have respect for time and nondemonstrative knowledge

2. Avoid optimization; learn to love redundancy

3. Avoid prediction of small-probability payoffs—though not necessarily of ordinary ones

4. Beware the "atypicality" of remote events

5. Beware moral hazard with bonus payments

6. Avoid some risk metrics (mediocristan in extremistan)

7. Positive or negative Black Swan?

8. Do not confuse absence of volatility with absence of risk

9. Beware presentations of risk numbers

pp.374-376:

The Ten Principles for a Black Swan-Robust Society:

1. What is fragile should break early, while it's still small.

2. No socialization of losses and privatization of gains.

3. People who were driving a school bus blindfolded (and crashed it) should never be given a new bus.

4. Don't let someone making an "incentive" bonus manage a nuclear plant—or your financial risks.

5. Compensate for complexity with simplicity.

6. Do not give children dynamite sticks, even if they come with a warning label.

7. Only Ponzi schemes should depend on confidence. Governments should never need to "restore confidence."

8. Do not give an addict more drugs if he has withdrawal pains.

9. Citizens should not depend on financial assets as a repository of value and should not rely on fallible "expert" advice for their retirement.

10. Make an omelet with broken eggs.

p. 376:

Then we will see an economic life close to our biological environment: smaller firms, a richer ecology, no speculative leverage—a world in which entrepreneurs, not bankers, take the risks, and in which companies are born and die every day without making the news.