---------------------------------------------------

Ever since the accident, Brian had lived in a vat. His body was crushed, but quick work by the surgeons had managed to salvage his brain. This procedure was now carried out whenever possible, so that the brain could be put back into a body once a suitable donor had been found.

But because fewer brains than bodies terminally fail, the waiting list for new bodies had got intolerably long. To destroy the brains, however, was deemed ethically unacceptable. The solution came in the form of a remarkable supercomputer from China, Mai Trikks. Through electrodes attached to the brain, the computer could feed the brain stimuli which gave it the illusion that it was in a living body, inhabiting the real world.

In Brian's case, that meant he woke up one day in a hospital bed to be told about the accident and the successful body transplant. He then went on to live a normal life. All the time, however, he was really no more than his old brain, kept alive in a vat, wired to a computer. Brian had no more or less reason to think he was living in the real world than you or I. How could he—or we—ever know differently?

Sources: The first meditation from Meditations by Rene Descartes, 1641; chapter 1 of Reason, Truth, and History by Hilary Putnam, 1982; The Matrix, directed by Larry and Andy Wachowski, 1999; Nick Bostrum's Simulation argument, www.simulation-argument.com.

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 151.

---------------------------------------------------

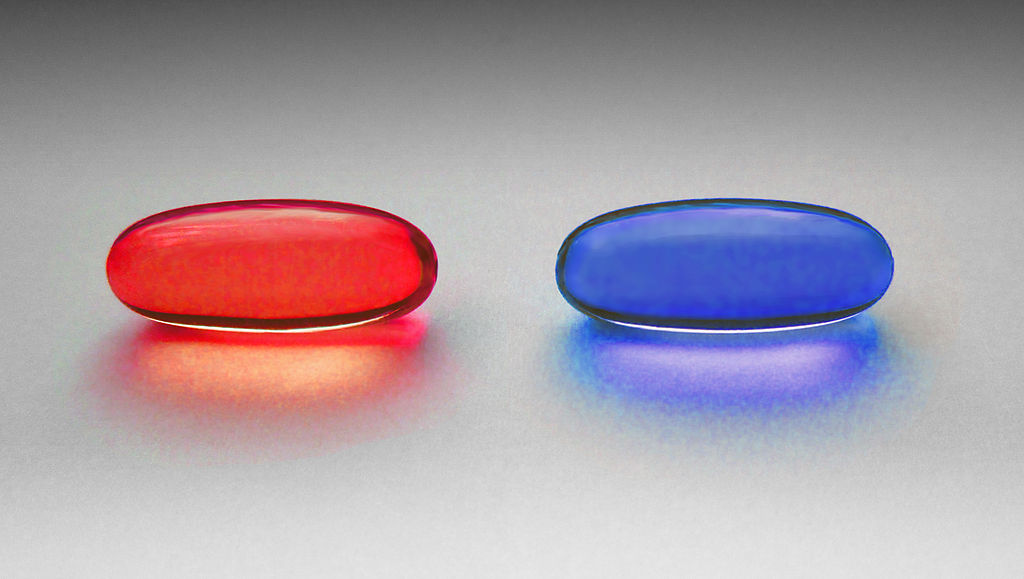

I've already grappled with this issue in three other thought experiments, but I'll do my best to bring something else to the table on Friday when I look at the new wrinkles in time presented here. Until then, try to act as though you've taken the blue pill and remained grounded in your reality.