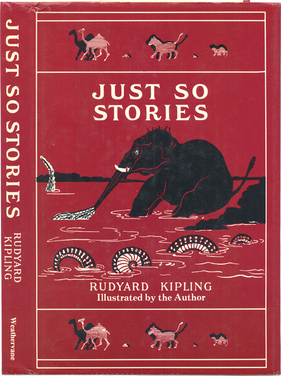

"...there was a heat wave in the Red Sea, and everybody took off all the clothes they had. ... the Rhinoceros took off his skin and carried it over his shoulder as he came down to the beach to bathe. ... He waddled straight into the water and blew bubbles through his nose, leaving his skin on the beach. Presently the Parsee came by and found the skin, and he smiled one smile that ran all round his face two times. Then he danced three times round the skin and rubbed his hands. Then he went to his camp and filled his hat with cake-crumbs, ... He took that skin, and he shook that skin, and he scrubbed that skin, and he rubbed that skin just as full of old, dry, stale, tickly cake-crumbs and some burned currants as ever it could possibly hold. Then he climbed to the top of his palm-tree and waited for the Rhinoceros to come out of the water and put it on. And the Rhinoceros did. He buttoned it up with the three buttons, and it tickled like cake crumbs in bed. Then he wanted to scratch, but that made it worse; and then he lay down on the sands and rolled and rolled and rolled, and every time he rolled the cake crumbs tickled him worse and worse and worse. Then he ran to the palm-tree and rubbed and rubbed and rubbed himself against it. He rubbed so much and so hard that he rubbed his skin into a great fold over his shoulders, and another fold underneath, where the buttons used to be (but he rubbed the buttons off), and he rubbed some more folds over his legs. And it spoiled his temper, but it didn't make the least difference to the cake-crumbs. They were inside his skin and they tickled. So he went home, very angry indeed and horribly scratchy; and from that day to this every rhinoceros has great folds in his skin and a very bad temper, all on account of the cake-crumbs inside."

How cute. Like the rest of these tales, this one is obviously intended to mostly just entertain us while perhaps reminding us of the characteristics of some different animals. Let's read this week's thought experiment now and see if it does the same.

---------------------------------------------------

"There is not a single piece of human behavior that cannot be explained in terms of our history as evolved beings," Dr. Kipling told his rapt audience. "Perhaps someone would like to test this hypothesis?"

A hand flew up. "Why do kids today wear their baseball caps the wrong way round?" asked someone wearing his peak-forward.

"Two reasons," said Kipling, confidently and without pause. "First, you need to ask yourself what signals a male needs to transmit to a potential mate in order to advertise his suitability as a source of strong genetic material, more likely to survive than that of his competitor males. One answer is brute physical strength. Now consider the baseball cap. Worn in the traditional style, it offers protection against the sun and also the gaze of aggressive competitors. By turning the cap around, the male is signaling that he doesn't need this protection: he is tough enough to face elements and the gaze of any who might threaten him.

"Second, inverting the cap is a gesture of non-conformity. Primates live in highly ordered social structures. Playing by the rules is considered essential. Turning the cap around shows that the male is above the rules that constrain his competitors and again signals his superior strength.

"Next?"

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 91.

---------------------------------------------------

I'm sure Baggini doesn't think this is equivalent to claiming there are cake crumbs tickling rhinoceroses from their insides, but he does have this to say in his explanation of the experiment he apparently penned himself:

"Evolutionary psychology is one of the most successful and controversial movements in thought of the last few decades. ... The controversy concerns just how far you can take this. The more zealous evolutionary psychologists claim that virtually every aspect of human behavior can ultimately be explained in terms of the selective advantage it gave our ancestors in their Darwinian struggle for survival. If you buy into this, it is not difficult to come up with plausible sounding evolutionary explanations for any behavior you choose. ... The trouble is that this suggests these are not genuine explanations at all, but "just so" stories. Evolutionary psychologists simply invent "explanations" on the basis of no more than prior theoretical commitment. But this gives us no reason to believe the accounts they offer rather than any other piece of speculation. ... Evolutionary psychologists are well aware of this criticism, of course. They argue that their accounts are much more than "just so" stories. For sure, they may generate hypotheses by indulging in the kind of speculation exemplified by Kipling's off-the-cuff explanation. But these hypotheses are then tested. However, there seem to be serious limits on how far testing is possible. ... [P]sychological and anthropological studies could show whether males in different cultures make public displays of their strength, as evolutionary psychologists would predict. What you can't do, however, is test whether any particular behavior, such as inverting one's baseball cap, is a manifestation of this tendency to display strength or is the result of something quite different. The big argument between evolutionary psychologists and their opponents is thus mainly concerned with how much can be explained by our evolutionary past."

This is nonsense. If Baggini can find an evolutionary psychologist who would actually purport such a simple-minded analysis as his Dr. Kipling, then I'll join him in damning that person's logic. But any serious scientist I've read on this subject would also admit that wearing a baseball cap the right way around could display the intellectual strength of the ability to use tools correctly for a purpose that would enhance one's survival. Wearing the cap the right way around may also signal allegiance to one social group over another, which the individual believes is a more advantageous group to identify with (baseball cap conservatives rather than rebels in this case). So either baseball cap option could be "explained" from an evolutionary perspective, but that's precisely the point. We've evolved to have the power to choose from among a range of options to find the right ones that work for the survival of life over the long term. The main thing in evolutionary studies—psychology in this case, or philosophy in mine—is that we human animals can only draw from the range of all the forces that shaped us over our evolutionary history. Those are the choices we have for explaining and analysing why certain choices may be made. What other forces could be at play?

Sure, evolutionary zealots could go too far. But the history of philosophers inventing religious motivations of supernatural origin shows they are much more likely to contain "just so" stories than any modern sophisticated evolutionary thinker. Baggini may be able to find straw men out there who have naively acted like his Dr. Kipling, but that's all they'll be. Straw men. Straw men who got that way because one day they were playing in a barn when they took out and shook out their bones we could look at.....