—Bertrand Russell, Philosophy and Politics

While scientists were performing astounding feats of disciplined reason [during the Enlightenment], breaking down the barriers of the “unknowable” in every field of knowledge, charting the course of light rays in space or the course of blood in the capillaries of man’s body -- what philosophy was offering them, as interpretation of and guidance for their achievements was the plain Witchdoctory of Hegel, who proclaimed that matter does not exist at all, that everything is Idea (not somebody’s idea, just Idea), and that this Idea operates by the dialectical process of a new “super-logic” which proves that contradictions are the law of reality, that A is non-A, and that omniscience about the physical universe (including electricity, gravitation, the solar system, etc.) is to be derived, not from the observation of facts, but from the contemplation of that Idea’s triple somersaults inside his, Hegel’s, mind. This was offered as a philosophy of reason.

—Ayn Rand, For the New Intellectual

Hegel is not a philosopher. He is no lover or seeker of wisdom—he believes he has found it. [...] By the end of the Phenomenology [of Spirit], Hegel claims to have arrived at Absolute Knowledge, which he identifies with wisdom. Hegel's claim to have attained wisdom is completely contrary to the original Greek conception of philosophy as the love of wisdom, that is, the ongoing pursuit rather than the final possession of wisdom.

—Glenn Alexander Magee, Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition

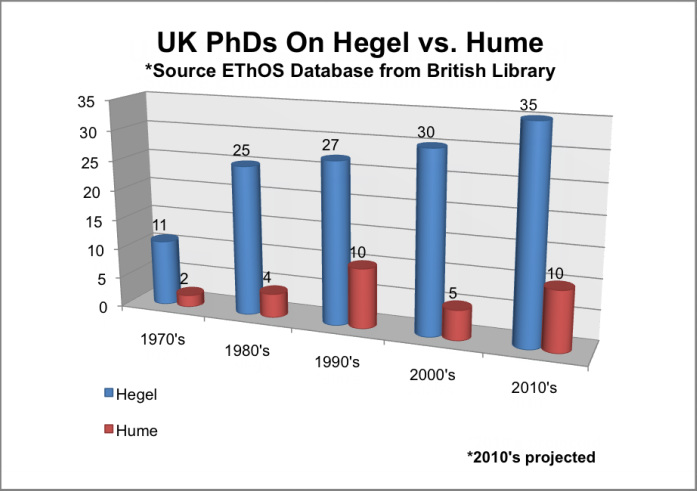

A few weeks ago, I profiled David Hume in this series on the survival of the fittest philosophers and I found that he was far and away the #1 favorite philosopher among academic professionals. People cited his empirically justified naturalistic beliefs, clarity of thought, and just the fact that he seemed like he'd be a good dinner guest as the reasons for their selection. Keeping all of that in mind about Hume, and after reading the quotes above about Hegel, who do you think would be more popular in terms of driving PhD research? Think again.

I pulled the data for this chart from searches through the British Library's Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS), which has over 350,000 PhD dissertations catalogued in it. I first searched for "Hegel" hoping to see that interest in his works was waning, but it has in fact been growing consistently through the decades. I then searched for "Hume" hoping to see that maybe Hegel's relative growth was small potatoes in the larger scheme of things, but in fact, I found just the opposite. Study of Hegel dwarfs Hume and produces terrible mouthfuls for titles that only an aspiring pseudo-intellectual could possibly conceive of. (The clear winner in that competition had to be this one: "Dialectic as the truth of reality and thought: a prolegomenon to the reconceptualisation of dialectic.") What does this say about society and academia? Is it any wonder scientists such as Stephen Hawking, Lawrence Krauss, and Neil deGrasse Tyson have taken to bashing philosophy as a useless pursuit? Just look at Hegel's own words and my evaluation of his major thoughts to see where they are coming from.

Philosophy is by its nature something esoteric, neither made for the mob nor capable of being prepared for the mob.

The great thing however is, in the show of the temporal and the transient to recognize the substance which is immanent and the eternal which is present.

History, is a conscious, self-meditating process—Spirit emptied out into Time; but this externalization, this kenosis, is equally an externalization of itself; the negative is the negative of itself.

Matter possesses gravity in virtue of its tendency towards a central point. It is essentially composite; consisting of parts that exclude each other. It seeks its Unity; and therefore exhibits itself as self-destructive, as verging towards its opposite ... Spirit, on the contrary, may be defined as that which has its centre in itself. It has not a unity outside itself, but has already found it; it exists in and with itself. Matter has its essence out of itself; Spirit is self-contained existence.

Spirit is knowledge; but in order that knowledge should exist; it is necessary that the content of that which it knows should have attained to this ideal form, and should in this way have been negated. What Spirit is must in that way have become its own, it must have described this circle; then these forms, differences, determinations finite qualities, must have existed in order that it should make them its own. This represents both the way and the goal—that Spirit should have attained to its own notion or conception, to that which it implicitly is, and in this way only, the way which has been indicated in its abstract moments, does it attain it. Revealed religion is manifested religion, because in it God has become wholly manifest. Here all is proportionate to the notion; there is no longer anything secret in God.

This is pure nonsense!! And there's so much of it!!!

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Georg Hegel (1770-1831 CE) was a German philosopher and one of the creators of German Idealism. His historicist and idealist account of the total reality as a whole was an important precursor to continental philosophy and Marxism.

Survives

Needs to Adapt

Hegel's dialectic was most often characterized as a three-step process, "thesis, antithesis, synthesis" - namely, that a "thesis" (e.g. the French revolution) would cause the creation of its "antithesis" (e.g. the reign of terror that followed), and would eventually result in a "synthesis" (e.g. the constitutional state of free citizens). The three-step process is a nice way to characterize a methodical search for knowledge. Propose a thesis, find the antithesis, let them compete and form a synthesis. Repeated ad-infinitum, this leads to powerful understanding. Hegel misunderstands the causation though as coming from the thesis itself rather than from the search for knowledge, which found the thesis lacking and simply proposed a new idea. Hegel goes further off the rails after this.

Gone Extinct

The fundamental notion of Hegel's dialectic is that things or ideas have internal contradictions. From Hegel's point of view, analysis or comprehension of a thing or idea reveals that underneath its apparently simple identity or unity is an underlying inner contradiction. This contradiction leads to the dissolution of the thing or idea in the simple form in which it presented itself and to a higher-level, more complex thing or idea that more adequately incorporates the contradiction. Hegel's main philosophical project was to take these contradictions and tensions and interpret them as part of a comprehensive, evolving, rational unity that, in different contexts, he called "the absolute idea" or "absolute knowledge.” These contradictions and tensions are a process. They are not some rational unity. They are the hallmark of knowledge evolving towards the absolute knowledge. They are the hallmark of an evolution of philosophy.

Hegel's philosophy has been labeled by some critics as obscurantist, with some going so far as to refer to it as pseudo-philosophy. His contemporary Schopenhauer was particularly critical, and wrote of Hegel's philosophy as, “a colossal piece of mystification which will yet provide posterity with an inexhaustible theme for laughter at our times, that it is a pseudo-philosophy paralyzing all mental powers, stifling all real thinking, and, by the most outrageous misuse of language, putting in its place the hollowest, most senseless, thoughtless, and, as is confirmed by its success, most stupefying verbiage.” Excellent summation from Schopenhauer. To look at the scientific method winnowing down hypotheses through an evolutionary battle of survival of the fittest ideas, and calling all the surviving and expiring ideas part of some unitary whole is just to re-label reality as “everything we have seen.” Hegel does nothing to further our understanding and fails to recognize the wisdom of the truths that survive.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It saddens me greatly to see the research facts above about Hegel after reading the man's own words and agreeing with the highly critical evaluations of him from others who have come before me and who also had to bother with his writings. I sometimes think philosophers purposefully keep arguments alive—refusing to render judgment about what is right or wrong—just to ensure their job security. But I suppose this is the penalty we pay in a field that a) recognizes that all knowledge is probabilistic, and b) is confined to nebulous questions that once clarified give birth to new scientific disciplines. Well, let's not pay that penalty any more than we have to. Next!