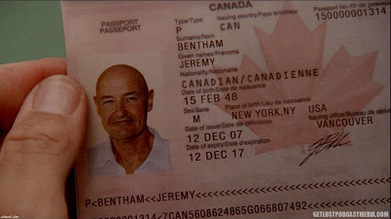

Photo from ABC's TV Show Lost

Photo from ABC's TV Show Lost Fortunately, Bentham the philosopher was much less of a waste of time, given the direction he sent our thoughts by being one of the founders of utilitarianism. In A Fragment on Government, Bentham laid down what was to become the fundamental axiom of this school of morality by saying, "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong." Bentham's definitions for happiness came down simply to feelings of pleasure and pain, but as modern cognitive psychology now teaches us, these sensations can be driven by our beliefs, which can be entirely subjective, relative only to the conventions of a group, and grounded in nothing objective from reality. Still, by paying attention to the best conventions that society had agreed upon in his day, Bentham ended up building logical arguments for right and wrong action that were independent of religious dogma and were extremely influential—if not entirely persuasive to more rigorous philosophers to follow. Here's more from my examination of Bentham:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He is best known for his advocacy of utilitarianism.

Survives

Bentham's position included arguments in favor of individual and economic freedom, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the end of slavery, the abolition of physical punishment (including that of children), the right to divorce, free trade, usury, and the decriminalization of homosexual acts. He also made two distinct attempts during his life to critique the death penalty. Bentham is widely recognized as one of the earliest proponents of animal rights - he argued that the ability to suffer, not the ability to reason, should be the benchmark in determining their proper treatment. The survival of all of these ideas into the modern age shows how Bentham’s philosophy was facing the right direction.

Needs to Adapt

Bentham was one of the main proponents of Utilitarianism - an ethical theory holding that the proper course of action is the one that maximizes the overall happiness. By happiness, he understood it as a predominance of pleasure over pain. Utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism, meaning that the moral worth of an action is determined only by its resulting outcome, and that one can only weigh the morality of an action after knowing all its consequences. Maximum happiness comes from the joy of long-term survival for life. This requires much wisdom of society and individuals. Once happiness is defined in this way, utilitarianism works well for an ethical theory. Long-term consequences of actions are often hard to determine though so we must be prudent in our experimentation and decisions.

Bentham’s hedonic calculus shows "expectation utilities" to be much higher than natural ones, so it follows that Bentham does not favor the sacrifice of a few to the benefit of the many. It should not be overlooked though that Bentham's hedonistic theory, unlike Mill's, is often criticized for lacking a principle of fairness embodied in a conception of justice. Bentham instead laid down a set of criteria for measuring the extent of pain or pleasure that a certain decision will create. The criteria are divided into the categories of intensity, duration, certainty, proximity, productiveness, purity, and extent. Using these measurements, he reviews the concept of punishment and when it should be used as far as whether a punishment will create more pleasure or more pain for a society. He calls for legislators to determine whether punishment creates an even more evil offense. Instead of suppressing the evil acts, Bentham is arguing that certain unnecessary laws and punishments could ultimately lead to new and more dangerous vices than those being punished to begin with. Bentham follows these statements with explanations on how antiquity, religion, reproach of innovation, metaphor, fiction, fancy, antipathy and sympathy, begging the question, and imaginary law are not justification for the creation of legislature. In addition to the multiplier affect of utilities, no minorities should ever be sacrificed for the good of a majority, no matter how maximum their number, because such sacrifice undermines the social cohesion required of our cooperative species. Bentham is on the right track with his calculations for pain and pleasure in determining the correct course of punishment to take. He misses the weight of the required tit for tat strategy though that stops cheaters from winning and undermining the stability of the evolutionary system.

Bentham, when arguing against the rights of man that were asserted in the Declaration of Independence, stated: "That which has no existence cannot be destroyed — that which cannot be destroyed cannot require anything to preserve it from destruction. Natural rights is simple nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense — nonsense upon stilts." Bentham is correct that rights do not exist in nature. They therefore cannot be destroyed, but they can be defined by societies of men and women, and require governments to preserve those agreements from destruction. To claim that rights are god-given or inalienable is nonsense on stilts, but we can walk on higher moral ground if we know where we are going.*

Gone Extinct

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

—--

* In my original review of Bentham, I misunderstood his "nonsense on stilts" to be referring to natural laws in general, not natural rights in particular. As stated elsewhere, morality does arise from analysing the history of our natural universe, so I said his thoughts on natural laws had gone extinct now that more science was in. However, when, researching his comments in more depth, I came to recognise that he was right about natural rights, but wrong in denying the benefit of a government creating them and then protecting them.