---------------------------------------------------

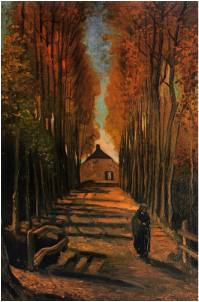

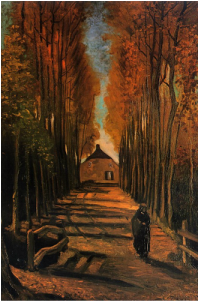

Avenue of Poplars at Dawn was set to join the ranks of van Gogh masterpieces. This "lost" work would sell for millions and generate volumes of scholarship comparing it to the two other paintings van Gogh made of the same scene at different times.

This pleased Joris van den Berg, for he, not van Gogh, had painted Avenue of Poplars at Dawn. Joris was an expert forger and he was certain that his latest creation would be authenticated as genuine. That would not only increase his wealth enormously but also give him tremendous satisfaction.

Only a few close friends knew what Joris was up to. One expressed very serious moral misgivings, which Joris had brushed off. As far as he was concerned, if this painting was judged to be as good as a van Gogh original, then it was worth every penny that was paid for it. Anyone who paid more than it was really worth just because it was van Gogh's own work was a fool who deserved to be parted from his money.

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 196.

---------------------------------------------------

The forger is obviously wrong, right? But why? Deceit itself isn't necessarily a bad thing, as illustrated by the common philosophical example that you shouldn't tell an inquiring murderer where his intended victim is. Baggini points this out before closing his discussion of this thought experiment by posing a challenge to us.

What seems to matter, therefore, is whether the lie serves a noble or base purpose, and what the consequences of the deception are. ... Could it be [the forger is making a point that] prices on the art market are not determined by aesthetic merit but by fashion, reputation, and celebrity? ... In this light, the forger can be seen as a kind of guerrilla artist, fighting for the true values of creativity in a culture where art has been debased and commodified. It is true that he is a deceiver. But no guerrilla war can be waged in the open. The system has to be picked apart from within, piece by piece. And the war will be won only when every work of art is judged on its own merits, not on the basis of the signature in the corner. That is, unless anyone can provide good reasons for believing that the signature really does matter...

So, are there good reasons for the signature to matter for a work of art? When I wrote about The Purpose of (My) Art, I said:

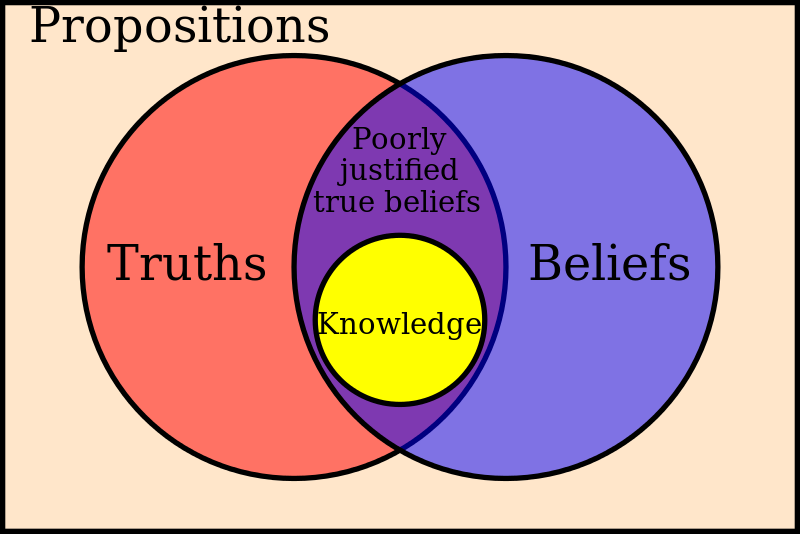

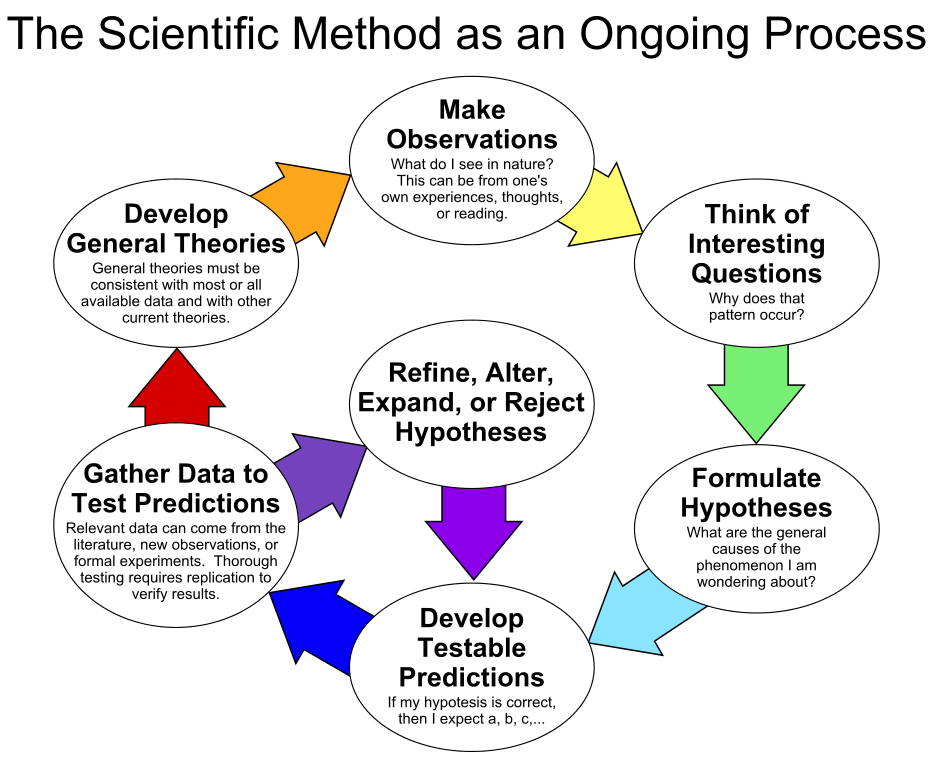

Art is knowledge applied to the emotions. Science finds knowledge; art uses knowledge to inspire. Art causes emotional responses, so it often draws emotional people to it, but great art is created by rational processes, filled with knowledge, fueled by emotion, and executed with skill. Bad art is blind emotion that purports falsehoods for truth.

From this, it is clear to me how Joris' forgery is bad art: he is literally purporting falsehood for truth and his work is fueled by emotions that are totally at odds with those coming from an original and sincere artist. This is why the signature really does matter. A true connection to the emotions and knowledge of the artist undoubtedly adds an extra dimension to any work of art, and that dimension can even become priceless whenever such a connection is deemed irreplaceable and full of inspirational beauty. Of course, if someone wanted to buy Joris' forgery with the goal of spreading his guerrilla message of snark, which attempts to undermine artistic integrity, then they are welcome to do so and pay for that what they will. But to me, that's a cheap message which does nothing to inspire.