I thought I’d be wrapping up this series with this summary, but my research shows that I really ought to have at least one more post after this to go over the traditional objections to a materialist account of consciousness. If my stated theory can answer all of those, then I’ll at least have a case for a coherent (if not correct) theory. On to the summary!

Preface — Epistemological and Metaphysical Background

According to an evolutionary worldview, the universe is always changing, we cannot see what the future will bring, and one can never get outside of it all to gather objective facts about the true state of the world. Therefore, knowledge cannot be justified, true, belief, as Plato thought. Knowledge can only ever be justified, beliefs, that are currently surviving our best rational tests. Knowledge is always provisional, and there is no bedrock upon which certainty can rest. (For now. Even that fact isn’t known for sure.)

To live, we must act. To decide upon actions from this state of fundamental ignorance, we must start with hypotheses and then test them. In evolutionary philosophy, my first tenet is the first hypothesis that is necessary to get us off the ground and running.

1. We live in a rational, knowable, physical universe. Effects have natural causes. No supernatural events have ever been unquestionably documented.

Through the eons of the entire age of life, and over all the instances of individual organisms acting within the universe, the ability of life to predict its environment and continue to survive in it has required that the universe must be singular, objective, and knowable. If it were otherwise, life could not make sense of things and survive here. We may never know if that is absolutely true, but so far that knowledge has survived. The objective, physical, natural, material existence of the universe may indeed be an assumption, but as a starting point, it seems to be the strongest knowledge we have. All previously uncovered mysteries have not changed this fact, so rationality dictates that we ought not to abandon it without good cause.

Before life emerged, all evidence points to a universe made of matter that interacted according to the fundamental laws of physics and then chemistry. All objects were affected by forces, but there were no subjects, minds, intentions, or consciousness. So, how did we get from physics to chemistry to biology? And how might consciousness suddenly appear during that time?

Hypotheses on the Mysteries of Abiogenesis and The Hard Problem

First, let’s look at the emergence of life. We may never know for sure how it actually happened. There may never be a way to find conclusive evidence or rule out all but one possibility. But the hypothesis that is a leading contender and makes the most sense to me right now is known as the “RNA World” hypothesis. Nobel Prize winner Jack Szostak’s work on this is explained very simply in a short video called The Origin of Life, and there is a much longer video series on the topic as well. I’ve covered this in more depth in a previous post, but a quick overview is that polymer chains and membranes form spontaneously in the environment and it’s very plausible to see how a simple 2-component system might form that can eat, grow, contain information, replicate, and evolve, simply through thermodynamic, mechanical, and electrical forces. That would kickstart evolution, which means the development of life would be off and running towards the present day. No ridiculous improbabilities are needed, no supernatural forces, and no lightning striking a mud puddle. Just chemistry and mechanical activity.

This leads us to a simple explanation for life, which is defined as something that preserves, furthers, or reinforces its existence in the given environment. There are seven traits currently considered to enable this kind of self-prolonged existence: organization, growth, reproduction, response to stimuli, adaptation, homeostasis, and metabolism. We can now see how physics plus chemistry plus natural selection might have led to all of these traits. But what about consciousness?

This is basically the hard problem as coined by David Chalmers. We have subjective experience. Evolutionary studies have shown us that there is an unbroken line in the history of life. But water and rocks don’t appear to have anything like consciousness. So, how can inert matter ever evolve into the subjective experience that we humans undoubtedly feel?

Chalmers has proposed that subjective experience may be a fundamental property of the universe, like the spin of electromagnetism. I have come to accept that as a likely hypothesis. All matter is affected by the forces of physics and chemistry. But until that matter is organized into a living subject that is capable of responding to those forces in such a way as to remain alive, it makes no sense to talk of non-living matter as ‘feeling’ or ‘experiencing’ those forces. Inert matter has no structure capable of living through subjective activities. Panpsychism claims that minds (psyche) are everywhere, and they don’t need physics and matter to exist. But this raises innumerable difficulties, including an enormous change to one’s metaphysics that supposedly cannot be detected by science. What I hypothesize instead is that the forces of physics are everywhere, and it is a fundamental property of the universe that these forces are felt subjectively when subjects emerge. Since the Greek for force is dynami, I would say the universe has pandynamism rather than panpsychism. The psyche only originates and evolves along with life. This psyche expands as the living structures expand their capabilities of sensing and responding to these forces. And the ‘flavor’ of experiences within this psyche are utterly dependent upon the underlying mechanisms of which particles of matter are being subject to which particular forces.

(For example, the retch of disgust from accidentally eating something harmful maps almost exactly onto the retch of moral disgust from accidentally witnessing something beyond the pale such as a mutilated dead body. These experiences come from very different sources, and they process very different bits of information, so we might expect them to feel very different, but we know from neuroscience that the brain has duct-taped the feelings of moral disgust onto the existing architecture for gustatory disgust and that is what explains the similar conscious experience. This is another striking bit of support for a materialist understanding of consciousness.)

A New Category of Forces Arise

So, the theories of the RNA World and pandynamism get us from the inert landscape of the early universe to the rich and vibrant present-day world with biology and subjective experience. Physicalism still holds as a viable hypothesis for the metaphysics of the universe if these theories are correct. And this view makes it clear that something else also emerges with the emergence of life. Given that living things are (to the best we know) merely structures of matter that have come to be organized so as to be self-sustaining and self-replicating, two new categories of things in the world appear which are related to that: 1) things that help life stay alive, and 2) things that harm life from staying alive. That division has no meaning in physics or chemistry, but they are fundamental once biology emerges. Through the trials and errors of natural selection, living systems become sensitive to these positive and negative aspects of the world and they respond accordingly. In science, something exists to the extent that it exerts causal power over other things. Gravity exists because it exerts power over mass. Electricity exists because it exerts power over charged particles. Similarly, the power these categories exert over living things implies they exist too. I call them ‘biological forces’.

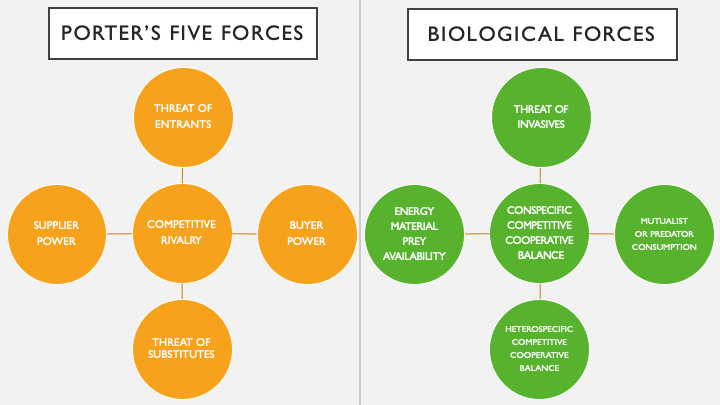

So, what do these biological forces look like? My conception is that they look like Porters Five Forces from the business world, which maps the competitive and cooperative forces that affect any organization as it tries to stay profitable (aka alive) in its industrial ecosystem. I hypothesize that this framework, taught in MBA curricula around the world, actually works because it is a fractal of the competition and cooperation that all life must navigate in its own ecosystems. These forces can be depicted side by side to make the analogy clear.

Therefore, in biology, there are 1) battles for consumption of upstream inputs of energy, material, or prey (a la suppliers); 2) battles for consumption of downstream outputs by mutualists, micro- or macroscopic predators (a la buyers); 3) battles with potentially invasive species (a la threat of entrants); 4) battles with current niche competitors from heterospecifics in other species (a la substitutes); and 5) the balance between competition and cooperation among conspecifics from the same species (a la competitive rivalry).

In the great interrelated web of life, any individual or species can play any of these parts depending on how you define the circle around an ecosystem for analysis. We all get eaten at some point. If biological behaviour is determined, it is not by the laws of physics and chemistry, but by the unwritten laws of these biological forces. However, just as the complexity in the system makes Porter’s Five Forces seemingly impossible to calculate with precision, this is even more true for anyone hoping to calculate outcomes from biological forces. Still, we can illustrate them and discuss their relative strengths to aid in analysis and understanding of life and its choices. This brings us to a place where we can now propose a new definition for consciousness.

An Evolutionary Theory of Consciousness

In my (sorta) brief history of the definitions of consciousness, I noted that previous attempts stretch all the way from consciousness being something as small as “the private, ineffable, special feeling that only we rational humans have when we think about our thinking,” right on down to it being “a fundamental force of the universe that gives proto-feelings to an electron of what it’s like to be that electron.” That’s why the Wikipedia entry on consciousness notes:

“The level of disagreement about the meaning of the word indicates that it either means different things to different people, or else it encompasses a variety of distinct meanings with no simple element in common.”

I believe the shape of a proper answer comes from Dan Dennett’s 2016 paper “Darwin and the Overdue Demise of Essentialism,” where he said:

“We should quell our desire to draw lines. We can live with the quite unshocking and unmysterious fact that there were all these gradual changes that accumulated over many millions of years. … The demand for essences with sharp boundaries blinds thinkers to the prospect of gradualist theories of complex phenomena, such as life, intentions, natural selection itself, moral responsibility, and consciousness.”

Indeed. But based on the story of abiogenesis outlined above, I think that a natural joint to carve a philosophical place for consciousness is in the biological realm. The emergence of life is sufficiently hazy and fuzzy in its origin so as to cast doubt on any overly specific claim that one particular molecular structure came together and suddenly turned consciousness on like a light switch. But no one needs to find such a grain of sand that turned a pile into a heap. We’re looking for a gradualist theory of the complex phenomena of consciousness, and its development along with life fits that bill.

This binding of consciousness to life also fits the etymological root of the word. The English word ‘conscious’ originally derived from the Latin conscius where con meant ‘together’ and scio meant ‘to know’. According to this literal interpretation, to be conscious would be ‘to know’, which requires a knower. And to ‘know together’, this conscious thing would need to know at least two things. Do sub-atomic particles feeling fundamental forces meet these criteria? No. Do elements from the periodic table feeling intermolecular forces meet these criteria? Also no. Do living things feeling biological forces meet these criteria? Yes. Once chemistry makes the jump to biology, the resulting proto-life forms have a defined self and they begin to compete for resources with other potential entrants, substitutes, or conspecifics in order to self-replicate and survive. They react to the world as if they know what they are and what they need. Thus:

Consciousness, according to this evolutionary theory, is an infinitesimally growing ability to sense and respond to any or all biological forces in order to meet the needs of survival. These forces and needs can vary from the immediate present to infinite timelines and affect anything from the smallest individual to the broadest concerns (both real and imagined) for all of life.

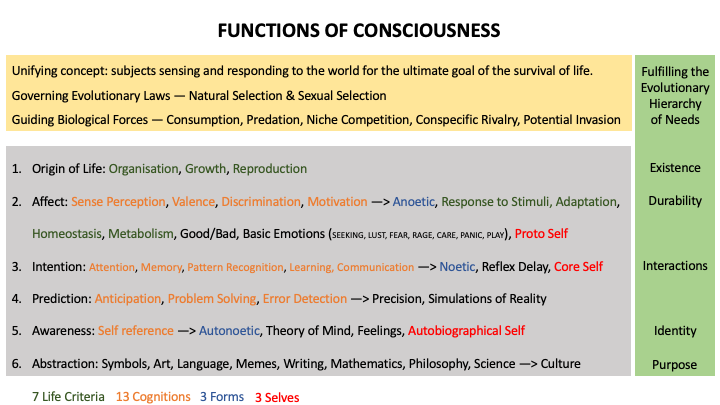

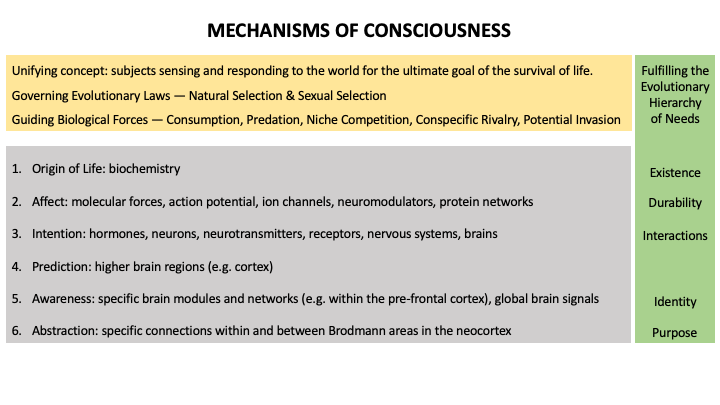

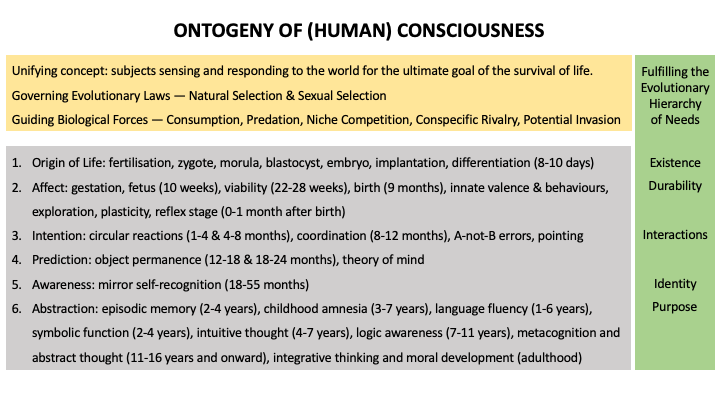

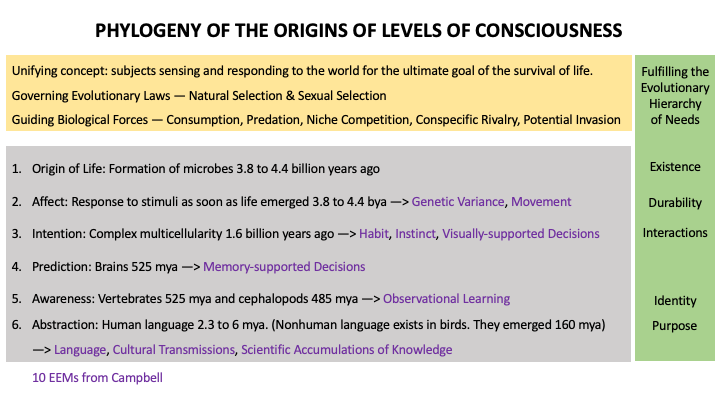

Such a definition accords with our intuitions to exclude non-living matter from consciousness studies. Rocks and water just don’t respond to any threats to their existence. But all living things do. And in an incredibly wide and diverse manner. In order to map the contours of such a broad definition, I spent several posts conducting a Tinbergen analysis of the functions, mechanisms, ontogeny, and phylogeny of consciousness, which is the standard procedure in evolutionary studies for coming to know all of the elements of any biological phenomenon. That massive review resulted in the following four charts:

2) Affect: This is the valence, tone, or mood that is capable of distinguishing differences between good stimuli as opposed to bad ones, which results in responses of graduated arousal and intensity. Mark Solms calls this the primary experience and purpose of consciousness. He asks, rhetorically, how can affective arousal (i.e., the arousal of feeling) go on without any inner feel? It cannot. This accords with my theory of pandynamism, where such feelings are felt subjectively as soon as subjects appear and are affected by biological forces. At first, these affects will generate what we think of as instinctual unconscious reactions. These can involve any or all of Jaak Panksepp’s seven basic emotions (in capital letters to denote a distinction between them and their common usage): SEEKING, FEAR, RAGE LUST, PANIC, CARE, and PLAY. Later, once many more structures have evolved, these affects can be registered, and eventually named, in conscious awareness.

3) Intention: This development in consciousness marks the ability of one reaction to interrupt or override others within an organism. From the perspective of an outside observer, choices appear to be made and there is a narrative sequence to life. Like affect, this can take place unconsciously within humans, so presumably it can in other forms of life as well, but it does empirically exist in very simple life using cognitive abilities such as memory, pattern recognition, and learning. Much later in evolutionary history, this can also be accessed and rationally considered in order to create extremely complex and far-ranging intentions.

4) Prediction: Once intentions exist (either one’s own or the intentions of others), the next development in consciousness is to take them into account by predicting how intentions will interact with the world. Organisms no longer just respond to the present by building up memories of the past; they begin to guess the future too. This appears to happen only in animals with brains that have neuroplasticity and can learn from experience. It also would seem that predictions about the intentions of others are particularly vital, which would explain why neurons and brains appear to have emerged during the Cambrian explosion due to the onset of predation. The success or failure of one’s predictions about their predators or prey would have been a powerful driver for change in any arms race occurring in this new dimension of consciousness. Surprise and uncertainty would be a bad emotion for any prediction, which would eventually help to hone the development of feelings of precision to extremely high levels.

5) Awareness: The next level of consciousness comes in now that structures have evolved to trigger affective emotions in the present (level 2), evaluate the past to make complex choices (level 3), and predict further and further into the future what the actions of the self and others may result in (level 4). The interaction and comparison of these three phenomena allows for the dawning of awareness of a self that is different from others. The richness of this distinction grows with the number of sensations that are able to be evaluated against one another within more and more sophisticated models of elements of the world. Studies have shown that conscious awareness is indeed necessary for some types of learning that give organisms additional plasticity to respond to new and novel stimuli in their environment, thus cementing the evolutionary advantage of gaining and retaining this ability.

6) Abstraction: The final level of consciousness in this hierarchy comes when models of reality go beyond mere direct representation and begin to use symbolic representations to evoke, communicate, and manipulate thoughts and feelings about the world. While nonhuman animals have displayed rudimentary or latent abilities for abstraction, the emergence and development of this capability in humans has been of such enormous import that it is considered the latest of the major transitions of evolution. Symbols, art, and language have driven the cultural evolution of memes, writing, mathematics, philosophy, and science that make up all of the powerful products of human culture. The causes for the emergence of this type of consciousness are mysteriously shrouded in the history of one species at the moment, but there is no denying the power, for good or for ill, that this has enabled. May our fuller grasping of the biological forces that affect the consciousness of all of life motivate us to realize what good is and bring it into fruition.

Related Definitions

To wrap up this discussion, and to help avoid some confusion, here are a few definitions of common terms in consciousness studies which sometimes differ between technical and folk usages. Where such differences exist, I have chosen a definition that best fits with my concept of consciousness as outlined above.

Accessible: This adjective is used to refer to the contents of consciousness that humans are able to recall and report upon. It is contrasted against the unconscious and inaccessible contents that may still drive behavior.

Attention: According to Michael Graziano and his attention schema theory, attention is the basic ability of a nervous system to focus on a few things at a time and process them deeply. Some forms of attention go back possibly all the way to the beginnings of nervous systems. Graziano thinks attention comes in very early in evolution, and over time it becomes more and more complex. There’s central attention, sensory attention, more cognitive kinds of attention, and they emerge gradually over this sweep of history from about half a billion years ago up to the present. Global Workspace Theory says attention is achieved by attending to signals as they become stronger and stronger compared to other signals. At some point, the signals become so strong that they reach a state called ‘ignition’ when they can then influence wide networks around the brain. Once that occurs, we humans can talk about that signal, we can move toward it, and we can remember it later.

Bottom-up vs. Top-down: In neuroscience, these terms describe specific directions of information processing. Sensory input is typically considered bottom-up, while higher cognitive processes, which have more information from other sources, are considered top-down. A bottom-up process is characterized by an absence of higher-level direction, whereas a top-down process is driven by other cognition, such as from goals or targets. In reality, there is a multi-directional feedback loop among these systems, and any talk of top-down control should not be meant to signify a homunculus in the brain, a designer from on high, or a skyhook that acts independently from all other causes.

Cognition: Pamela Lyon lists 13 functional abilities of cognition that help organisms adapt to their environment. I have found that these are distributed throughout my hierarchy of consciousness and they have developed in a logical fashion that is also supported by empirical evidence from evolutionary history. These are: (1) sense perception — ability to recognize existentially salient features of the external or internal milieu; (2) affect — valence, attraction, repulsion, neutrality / indifference (hedonic response); (3) discrimination — ability to determine that a state of affairs affords an existential opportunity or presents a challenge, requiring a change in internal state of behavior; (4) motivation — teleonomic striving; implicit goals arising from existential conditions; (5) attention — awareness, orienting response; ability to selectively attend to aspects of the external and/or internal milieu; (6) memory — retention of information about a state of affairs for a non-zero period; (7) pattern recognition — intentionality, directedness towards an object; (8) learning — experience-modulated behavior change; (9) communication — mechanism for initiating purposive interaction with conspecifics (or non-conspecific others) to fulfill an existentially salient goal; (10) anticipation — behavioral change based on experience-based expectancy (i.e. if X is happening, then Y should happen), possibly evolved across generations, and which is implicit to the agent’s functioning; (11) problem solving — decision making, behavior selection in circumstances with multiple, potentially conflicting parameters and varying degrees of uncertainty; (12) error detection — normativity, behavioral correction, value assignment based on motivational state; and (13) self-reference— mechanisms for distinguishing “self” or “like self” from “non-self” or “not like self”.

Communication: This is described as, “an act of interchanging ideas, information, or messages, via words or signs, which are understood to both parties. Every living thing communicates in some way. Fish jump, sometimes for sheer joy. Birds sing their cadences to communicate a variety of purposes. Dogs bark, cats meow, cows moo, and horses whinny. These noises, or other interactions, communicate or transfer information of some kind. Communication is, at its core, a two-way activity, consisting of seven major elements: sender, message, encoding, channel, receiver, decoding, and feedback.” Note that this is distinct from language. See the definition of language below for comparison.

Conscious vs. Unconscious: These terms are generally used more like medical descriptions, corresponding to awake and aware (conscious) vs. asleep or unresponsive (unconscious). They can both be described using various scales of physical attributes (cf. the Glasgow Coma Scale) and both fit within my hierarchy of consciousness as being more or less able to sense and respond to the needs of remaining alive. (Note that I generally stay away from Freud’s usage of the unconscious mind as it is a mixed bag of insight and imagination that would take a lot of patience to unpack.)

Emotions vs. Feelings: In my previous writings on emotion, I noted that this is a complex psychophysiological experience where an individual's state of mind interacts with biochemical (internal) and environmental (external) influences. Emotions can be seen as mammalian elaborations of general vertebrate arousal patterns, in which neurochemicals (for example, dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin) step-up or step-down the brain's activity level, as visible in body movements, gestures, and postures. An influential theory of emotion is that of Lazarus: emotion is a disturbance that occurs in the following order: 1) cognitive appraisal—the individual assesses the event cognitively, which cues the emotion; 2) physiological changes—the cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response; 3) action—the individual feels the emotion and chooses how to react. Lazarus stressed that the quality and intensity of emotions are controlled through cognitive processes. I think these descriptions cover the broad evolutionary emergence and growth of affective feeling from the most basic valence in organisms even simpler than bacteria all the way to the sophisticated naming and therapeutic modification of human moods. Antonio Damasio tries to separate emotions from feelings, saying emotions are chemical reactions, while feelings are the conscious experience of emotions. This is overly confusing and unnecessary to me, and apparently Damasio is not always consistent with this usage either. If you consciously feel an emotion, you feel affect (level 2 in my hierarchy) and you have awareness (level 5 in my hierarchy). I find that easier to understand.

Evolutionary Hierarchy of Needs: When I define consciousness as the ability to sense and respond to any or all biological forces in order to meet the needs of survival, these are the needs that I am talking about. For full details, see my article about Replacing Maslow with an Evolutionary Hierarchy of Needs, but here are some important points to consider. There are many ways that the ultimate question of survival can be determined, and life has been slowly learning to sense and understand these over billions of years. For example, there are so many things that can kill you, your genes, your kin, or your species, and they can all do so in the immediate, medium, or very long term. Living organisms that can sense and respond to more and more of these threats are the ones that will last and emerge over time. Such organisms will sense many, many needs to meet all of the threats (and exploit all of the opportunities) in its environment. Each living organism’s unique genetic, environmental, and evolutionary histories are constantly leading to changes in the relative strengths of these needs, but at no point does something outside of the physical realm enter into the equation. All of these needs can be described through physical properties, even if the magnitude of their felt force cannot yet be calculated. The ever-growing list of threats and opportunities is why the needs of life are ever-growing too. The psychologist Abraham Maslow studied these for individual humans and produced his famous Hierarchy of Needs. I have generalized these and adapted them to apply to all of life, thereby producing something I call an Evolutionary Hierarchy of Needs. Starting at the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid, we see that the ‘physiological’ needs of the human are merely the brute ingredients necessary for ‘existence’ that any form of life might have. In order for that existence to survive through time, the second-level needs for ‘safety and security’ can be understood as promoting ‘durability’ in living things. The third-tier requirements for ‘love and belonging’ are necessary outcomes from the unavoidable ‘interactions’ that take place in our deeply interconnected biome of Earth. The ‘self-esteem’ needs of individuals could be seen merely as ways for organisms to carve out a useful ‘identity’ within the chaos of competition and cooperation that characterizes the struggle for survival. And finally, the ‘self-actualization’ that Maslow struggled to define could be seen as the end, goal, or purpose that an individual takes on so that they may (consciously or unconsciously) have an ultimate arbiter for the choices that have to be made during their lifetime. This is something Aristotle called ‘telos’. Taken as a whole, these are the needs that life must evolve to become more and more conscious of if it is to survive over longer and longer spans of time.

Evolutionary Epistemology Mechanisms: As part of Donald Campbell’s work defining the field of evolutionary epistemology, he settled on a 10-step outline that showed the broad categories of mechanisms that biological life has used to gain knowledge. I have found that these fit well within my hierarchy and in the same order along with my map of the phylogenetic history of consciousness (see chart above). These EEMs start with the earliest origins of life where problems were solved over generations through mere genetic variance alone, without any aids from motion or the formation of memories. That earliest slow accrual of genetic knowledge eventually led, according to Campbell, to the other mechanisms: movement, habit, instinct, visually-supported decisions, memory-supported decisions, observational learning from social interactions, language, cultural transmissions, and finally, scientific accumulations of knowledge.

Exteroception vs. Interoception: Exteroception is any form of sensation that results from stimuli located outside the body and is detected by exteroceptors, including vision, hearing, touch or pressure, heat, cold, pain, smell, and taste. Interoception is any form of sensation arising from stimulation of interoceptors and conveying information about the state of the internal organs and tissues, blood pressure, and the fluid, salt, and sugar levels in the blood.

Intentionality vs. Intentional Stance: Intentionality is a technical term in philosophy that was introduced by Franz Brentano in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. It should not be confused with the ordinary meaning of the word intention. While an intention is just an internal aim or goal, intentionality refers to mental directedness towards objects, as if the mind were a bow whose arrows could be properly aimed at different targets. It is also sometimes referred to as aboutness. On the other hand, the intentional stance has been defined by Daniel Dennett as an understanding that others' actions are goal-directed and arise from particular beliefs or desires. It is intentionality aimed at subjects. The understanding of others' intentions is a critical precursor to understanding other minds. Since the seminal (1978) paper by primatologists David Premack and Guy Woodruff entitled “Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?”, much empirical research has been devoted to the question of whether non-human primates can ascribe psychological states with intentionality to others. Call and Tomasello concluded in 2008 that chimpanzees understand others in terms of a perception-goal psychology, as opposed to a full-fledged, human-like belief-desire psychology. This is an interesting distinction in the way that minds may work.

Involuntary vs. Voluntary: In biology, involuntary control refers to bodily activity “not

under the control of the will of an individual.” These involuntary responses by muscles, glands, etc., occur automatically when required; many such responses, such as gland secretion, heartbeat, and peristalsis, are controlled by the autonomic nervous system and effected by involuntary muscle. Voluntary muscles, by contrast, are under our conscious control so we can move these muscles when we want to. These are the muscles we use to make all the movements needed in physical activity. Note that these two physiological terms are not concerned with the question of free will and whether ‘conscious control’ is ultimately under our control or not. (That is another large topic in metaphysics for another time.)

Language: This is defined as “a distinctly human activity that aids in the transmission of feelings and thoughts from one person to another. It is how we express what we think or feel—through sounds and/or symbols (spoken or written words), signs, posture, and gestures that convey a certain meaning. The purpose of language is making sense of complex and abstract thought. Whereas communication is an experience, language is a tool.” Language allows for much greater scale and scope in cognition. It increases our ability to make sense of the world compared to working memory alone. It vastly enlarges the recognition of patterns in the world. And language enables deep and precise exploration of the self and the world around us. The power of language is perhaps best displayed by Hellen Keller who did not always have it. She said, “Before my teacher came to me, I did not know that I am. I lived in a world that was a no-world. I cannot hope to describe adequately that unconscious, yet conscious time of nothingness. (…) Since I had no power of thought, I did not compare one mental state with another.”

Mind: The mind is “the set of faculties including cognitive aspects such as consciousness, imagination, perception, thinking, intelligence, judgement, language and memory, as well as noncognitive aspects such as emotion and instinct. Under the scientific physicalist interpretation, the mind is produced at least in part by the brain. The primary competitors to the physicalist interpretations of the mind are idealism, substance dualism, types of property dualism, eliminative materialism, and anomalous monism. There is a lengthy tradition in philosophy, religion, psychology, and cognitive science about what constitutes a mind and what are its distinguishing properties.” In this series, I have done my best to describe and defend a physicalist interpretation of all of these aspects of mind.

Qualia vs. Something-it-is-like vs. Subjective Experience: The term qualia derives from the Latin adjective qualis meaning “of what sort” or “of what kind” in a specific instance, such as “what it is like to taste a specific apple, this particular apple now.” There are many definitions of qualia, but one of the simpler and broader definitions is: “The 'what it is like' character of mental states. The way it feels to have mental states such as pain, seeing red, smelling a rose, etc.” This ‘what it is like’ is also a reference to Thomas Nagel’s paper What is it Like to Be a Bat? in which Nagel famously asserts that “an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism—something it is like for the organism.” In other words, it is the experience of being a subject, hence the other term for this phenomenon as subjective experience. The supposed ineffableness of qualia, the purported inability to describe “the redness” of a rose, is completely effable within the evolutionary theory of consciousness presented above. The hard problem of why the experience happens at all is assumed just to be a fundamental property of the universe, which arises in subjects once they evolve the structure to sense and respond to stimuli. After that, the “redness” is completely described by the Tinbergen analysis which shows the adaptive functions of seeing red, the mechanisms involved in sensing wavelengths of light in the red spectrum, the general phylogenetic history of how sensing red has evolved in our species, and the specific ontogenetic history of personal experience that the individual has had with different intensities of redness during their life. What else is left to explain?

Conclusion

For thousands of years of human history, including several hundred after the scientific revolution, the existence and diversity of life was a mystery because evolution and the processes of natural selection were unknown. Once Darwin gathered the evidence to make his case for the theory of evolution, much of that mystery evaporated and any hazy fog that obscured what life is all about has been slowly evaporating with more and more scientific exploration. Within such research, consciousness has remained behind a stubborn patch of murkiness, even after several decades of dedicated consciousness studies. Perhaps this has remained so because of the invisibility of biological forces (like the proverbial water surrounding a fish). Or perhaps it was because consciousness as a fundamental part of the physical universe (like gravity or electromagnetism) just hasn’t been accepted or explained via a hypothesis like pandynamism. Or perhaps consciousness just hasn’t been properly illuminated by a comprehensive analysis using Tinbergen’s framework for all biological phenomena. Now that I have gone through all three of these additions, however, perhaps the view of consciousness might finally become a bit clearer.

What do you think? Does this theory of consciousness make sense to you? What questions has it left unanswered? In my next post, I will check these ideas against the traditional objections to physicalist conceptions of consciousness, but please share your own in the comments below so I might consider them as well.

--------------------------------------------

Previous Posts in This Series:

Consciousness 1 — Introduction to the Series

Consciousness 2 — The Illusory Self and a Fundamental Mystery

Consciousness 3 — The Hard Problem

Consciousness 4 — Panpsychist Problems With Consciousness

Consciousness 5 — Is It Just An Illusion?

Consciousness 6 — Introducing an Evolutionary Perspective

Consciousness 7 — More On Evolution

Consciousness 8 — Neurophilosophy

Consciousness 9 — Global Neuronal Workspace Theory

Consciousness 10 — Mind + Self

Consciousness 11 — Neurobiological Naturalism

Consciousness 12 — The Deep History of Ourselves

Consciousness 13 — (Rethinking) The Attention Schema

Consciousness 14 — Integrated Information Theory

Consciousness 15 — What is a Theory?

Consciousness 16 — A (sorta) Brief History of Its Definitions

Consciousness 17 — From Physics to Chemistry to Biology

Consciousness 18 — Tinbergen's Four Questions

Consciousness 19 — The Functions of Consciousness

Consciousness 20 — The Mechanisms of Consciousness

Consciousness 21 — Development Over a Lifetime (Ontogeny)

Consciousness 22 — Our Shared History (Phylogeny)