Ethics

"Good is that which leads towards the long-term survival of life."

On my Philosophy 101 page, I wrote that ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is a branch of philosophy which seeks to address questions about morality; that is, about concepts like good and bad, right and wrong, justice, virtue, etc.

Since morality is concerned with norms of behaviour, it is only applicable to living things. Where there is no life, there is no morality. Therefore, we can draw a fundamental conclusion that morals must promote the survival of life if morality itself is to survive. Ethics are not some perfect rules shouted down from on high that we have to strive to discover. Ethics started from zero and have emerged over time (alongside the emergence of life) into more and more complex norms of behaviour. This is a classic example of Darwin's strange inversion of reasoning.

Such an evolutionary view of morality helps us modify and unite the three traditional camps of ethical systems. The first of these is consequentialism, which tries to determine if our actions will have good or bad consequences. Given the ultimate goal of ethics derived above, we can now empirically decide good and bad consequences from an evolutionary perspective. Good is that which leads towards the long-term survival of life. Harmful behaviours make the survival of life more fragile.

The second traditional ethical camp is deontology, or rule-based ethics. Adherents of this camp look for hard and fast rules to govern our actions. Examples include the Ten Commandments, the Golden Rule, or Kant’s categorical imperative. An evolutionary perspective tells us that there are no such eternal rules to be derived from on high. But knowing the ultimate consequences we are striving towards can help us derive rules and responsibilities for any given situation. These must be contextual, based on the environment they are concerned with. And since the environment is always changing, our rules must change along with the situation. Any insistence on permanent universals will remove our ability to adapt.

The final traditional camp in morality is concerned with virtue ethics, which can be traced back to Aristotle who tried to find character traits that are always inherently virtuous. Once again, an evolutionary perspective shows us this is impossible as virtues must be evaluated in the context of an ever-evolving environment. Still, an examination of our evolutionary past can give us a reliable list of characteristics that have often proven virtuous. And these may guide us during trials and errors through situations where ultimate consequences are especially difficult to know.

Summarising these arguments gives a three-pronged position for evolutionary ethics that is united in its purpose:

1. Consequentialism — avoid extinction, maximise survival

2. Deontology — act for the long-term survival of life

3. Virtue ethics — study what works and balance the needs of all

Since morality is concerned with norms of behaviour, it is only applicable to living things. Where there is no life, there is no morality. Therefore, we can draw a fundamental conclusion that morals must promote the survival of life if morality itself is to survive. Ethics are not some perfect rules shouted down from on high that we have to strive to discover. Ethics started from zero and have emerged over time (alongside the emergence of life) into more and more complex norms of behaviour. This is a classic example of Darwin's strange inversion of reasoning.

Such an evolutionary view of morality helps us modify and unite the three traditional camps of ethical systems. The first of these is consequentialism, which tries to determine if our actions will have good or bad consequences. Given the ultimate goal of ethics derived above, we can now empirically decide good and bad consequences from an evolutionary perspective. Good is that which leads towards the long-term survival of life. Harmful behaviours make the survival of life more fragile.

The second traditional ethical camp is deontology, or rule-based ethics. Adherents of this camp look for hard and fast rules to govern our actions. Examples include the Ten Commandments, the Golden Rule, or Kant’s categorical imperative. An evolutionary perspective tells us that there are no such eternal rules to be derived from on high. But knowing the ultimate consequences we are striving towards can help us derive rules and responsibilities for any given situation. These must be contextual, based on the environment they are concerned with. And since the environment is always changing, our rules must change along with the situation. Any insistence on permanent universals will remove our ability to adapt.

The final traditional camp in morality is concerned with virtue ethics, which can be traced back to Aristotle who tried to find character traits that are always inherently virtuous. Once again, an evolutionary perspective shows us this is impossible as virtues must be evaluated in the context of an ever-evolving environment. Still, an examination of our evolutionary past can give us a reliable list of characteristics that have often proven virtuous. And these may guide us during trials and errors through situations where ultimate consequences are especially difficult to know.

Summarising these arguments gives a three-pronged position for evolutionary ethics that is united in its purpose:

1. Consequentialism — avoid extinction, maximise survival

2. Deontology — act for the long-term survival of life

3. Virtue ethics — study what works and balance the needs of all

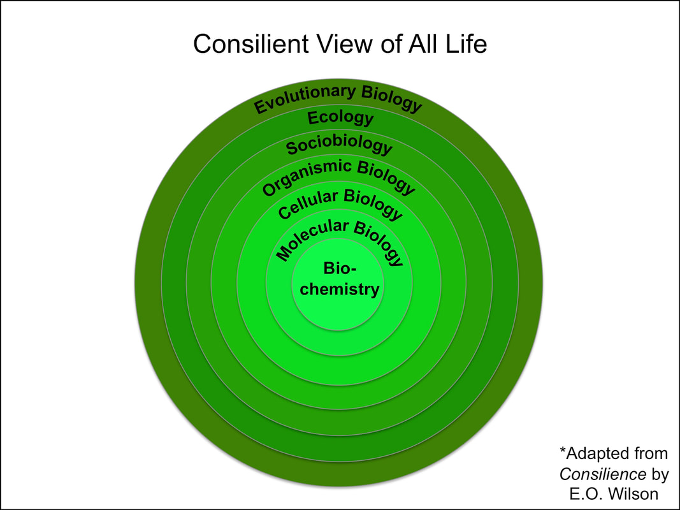

Since these moral rules are concerned with the survival of life in general, we can look to all of the fields of biology to inform our norms. Evolutionary history shows that all of life is related and interrelated. This is something that the evolutionary scientist E.O. Wilson talked about extensively in his book Consilience. This book was his attempt to unite all of the different fields of biology, which he felt were becoming too siloed and separate from one another. And the way that he proposed to do this was by organizing them into larger and larger circles of concern based on the magnitude of time and space. This gives us seven areas to consider for a consilient view of all life:

This picture contains all of the major fields of biology, and therefore it can act as a guide for how to study or care about all of the life that has ever existed or ever will. Maslow's hierarchy of needs is widely viewed as the best model we have for understanding the needs of our own species. So I wrote an essay adapting that hierarchy to make it generalisable for all of life and then used that evolutionary hierarchy of needs to examine the needs for all of life in the seven spheres in Wilson's consilient model. Understanding and balancing these needs will be a requirement for a full and rich evolutionary ethics.

For the most significant arguments for this view of evolutionary ethics, see these three peer-reviewed essays:

Bridging the Is-Ought Divide: Life is. Life ought to act to remain so.

Replacing Maslow With An Evolutionary Hierarchy of Needs

Rebuilding the Harm Principle: Using an Evolutionary Perspective to Provide a New Foundation for Justice

For the most significant arguments for this view of evolutionary ethics, see these three peer-reviewed essays:

Bridging the Is-Ought Divide: Life is. Life ought to act to remain so.

Replacing Maslow With An Evolutionary Hierarchy of Needs

Rebuilding the Harm Principle: Using an Evolutionary Perspective to Provide a New Foundation for Justice

Further Reading

For more details on my evolutionary ethics, here are some other essays I have written:

- Proposing an Objective, Godless Basis for Morality — A popular version of my first peer-reviewed paper, published in Humanist magazine.

- FAQs for Bridging the Is-Ought Divide

- Philosopher vs. Philosopher

- Walking in Hume’s Footsteps

- Bridging the Is Ought Divide

- When the Human in Humanism Isn't Enough — A proposal to change the definition of humanism in Humanist magazine according to my principles of evolutionary ethics. (This received a letter of support from Peter Singer.)

- Why the Human in Humanism Is Not Enough — A discussion I had with a Humanist who wrote a disparaging letter to the editor about my work.

- More on Evolution and Ethics — philosopher John Messerly posted comments I sent him on this subject

- My Draft Response to Sam Harris’ Moral Landscape Challenge

- Review of “What Happened to Tom”, a novella by Peg Tittle

- The summary section on ethics in What I Learned From 100 Philosophy Thought Experiments.

- Each individual thought experiment from that series that dealt with ethics:

- #58 Divine Command

- #95 The Problem of Evil

- #45 The Invisible Gardner

- #8 Good God

- #78 Gambling on God

- #60 Do As I Say, Not As I Do

- #71 Life Support

- #7 When No One Wins

- #99 Give Peace a Chance?

- #83 The Golden Rule

- #84 The Pleasure Principle

- #98 The Experience Machine

- #89 Kill and Let Die

- #96 Family First

- #22 The Lifeboat

- #27 Duties Done

- #50 The Good Bribe

- #100 The Nest Cafe

- #52 More or Less

- Questioning All This

- #26 Pain's Remains

- #91 No One Gets Hurt

- #76 Net Head

- #68 Mad Pain

- #61 Mozzarella Moon

- #69 The Horror

- #75 The Ring of Gyges

- #20 Condemned to Life

- Ethics posts from my series on knowing thyself:

- The Evolution of God

- The Arguments for God - Why Religion Will Go Extinct

- The World Without Religion

- Are Morals Just Rules for Survival?

- The Real Role of Science in Morality

Subscribe to Help Shape This Evolution

© 2012 Ed Gibney