Replacing Maslow with an Evolutionary Hierarchy of Needs

Note: This article was posted on Patheos.org on 4 October 2017, but was later taken down when its Atheist channel was removed.

However ugly the parts appear, the whole remains beautiful. A severed hand / Is an ugly thing, and man dissevered from the earth and stars and his history ... for contemplation or in fact ... / Often appears atrociously ugly. Integrity is wholeness, the greatest beauty is / Organic wholeness, the wholeness of life and things, the divine beauty of the universe.

--Excerpt from The Answer, a poem by Robinson Jeffers, 1936.

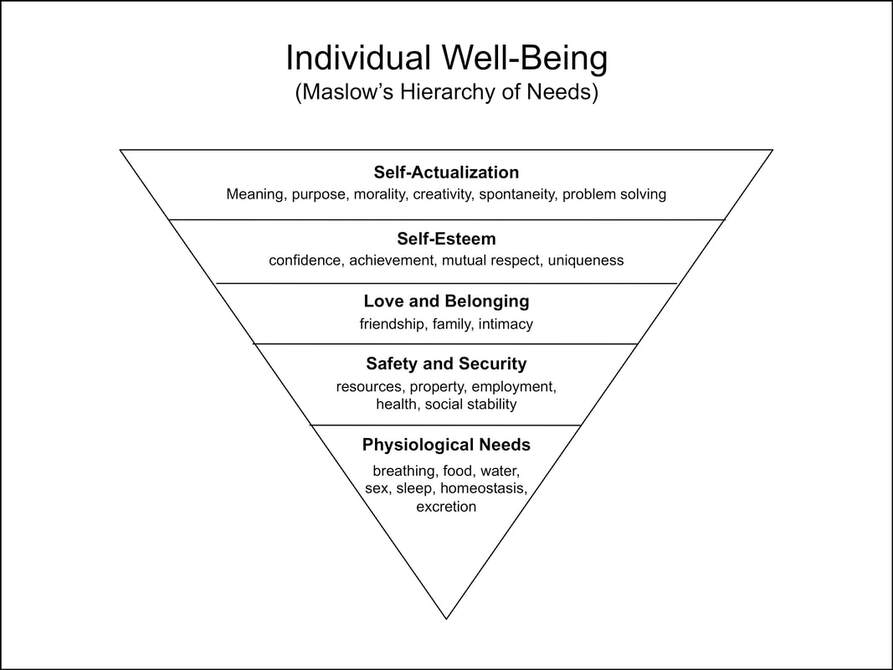

In 2018, the world will celebrate the 75th anniversary of Abraham Maslow’s classic paper that was published in Psychological Review and proposed a hierarchical approach to human motivation. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs — that pyramid constructed on a base of physiological needs, and proceeding upwards through safety and security, love and belonging, and self-esteem, before topping out with self-actualization — is well known to millions who have had any exposure to the field of psychology. Fulfill these needs, and you will be a fulfilled person. Philosophers would say you were flourishing, imbued with eudaimonia, and a shining example of well-being. From a modern evolutionary perspective, however, this is no longer enough.

Evolutionary thinking has, of course, already become deeply embedded in the field of psychology, and uncounted studies, papers, and theoretical counter-arguments have looked to use this to improve upon Maslow’s hierarchy. Last fall, Alice Andrews — a professor of psychology and evolutionary studies — shared a very thought provoking “work-in-progress” (her words) on this Sacred Naturalism site, which offered an update to Maslow that she called “evolutionary well-being.” In that post, Andrews also made note of a particularly important 2010 paper from Kenrick et al. titled “Renovating the Pyramid of Needs: Contemporary Extensions Built Upon Ancient Foundations,” which proposed an updated and revised hierarchy of needs based on “theoretical and empirical developments at the interface of evolutionary biology, anthropology, and psychology.” Both of these make for very insightful reading about the human condition. Andrews and Kenrick bring in deep understandings of modern evolutionary findings, and they seek to include issues of social or ecological concern in their discussions of the human psyche. Kenrick goes so far as to put “parenting” on the top of his pyramid of needs in an attempt to make evolutionary survival and reproduction of paramount importance. I think we can take these explorations further, however, in light of two additional evolutionary considerations.

The first is that for a species governed by gene-culture co-evolution, the reproduction and adaptation of memes is surely important too. Who did more for the survival of our species — Aristotle, or one of his neighbors who hypothetically managed to sire 13 children? Procuring food, water, and shelter, and expending resources on reproduction (by at least someof us) may be necessary ingredients for human genes to survive in the short term, but it takes wise and strategic cultural memes to generate robust and enjoyable survival over the long haul. If you agree that Aristotle did more for this than his fecund neighbor might have, then there must be a higher, more governing goal for humans than parenting. That leads to the second point to consider with these hierarchies: the fact that they mostly attempt to depict the needs of all homo sapiensin one single diagram, as if one person could or should do everything on them. This pictorial limitation hampers the much broader perspective — both sociologically and ecologically — that is not only available, but is in fact necessary, as I will describe below.

Redrawing the Hierarchy

Before attempting to sketch in the elements of this broader perspective, it proves helpful to consider the differences between the various hierarchies for individuals in order to see if there is something universal that might be used to harmonize and extend them. First off, what shape actually works best for illuminating this discussion? Maslow used a pyramid, but this seems to imply that the base needs must always remain more largely fulfilled than the higher ones. These base needs are certainly necessary, but an overemphasis on them leads to a shallow existence. Maslow also said that it was only typical to have lesser fulfillment at each progressive level. But this was not, unlike the pyramids at Giza, set in stone. In fact, if all is going very well, Maslow acknowledged that most of a person’s efforts could be aimed towards their higher goals. People often ignore hunger and even the need for social contact when they are preoccupied with their most important intellectual pursuits. Kenrick drew overlapping triangles to show this interplay. Andrews opted for a simple table of needs for goals; her lack of fixed architecture allows her levels to exist freely and overlap in any amount for their relative importance. During our most self-actualized moments, though, we might feel like Maslow’s pyramid should be flipped upside down.

--Excerpt from The Answer, a poem by Robinson Jeffers, 1936.

In 2018, the world will celebrate the 75th anniversary of Abraham Maslow’s classic paper that was published in Psychological Review and proposed a hierarchical approach to human motivation. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs — that pyramid constructed on a base of physiological needs, and proceeding upwards through safety and security, love and belonging, and self-esteem, before topping out with self-actualization — is well known to millions who have had any exposure to the field of psychology. Fulfill these needs, and you will be a fulfilled person. Philosophers would say you were flourishing, imbued with eudaimonia, and a shining example of well-being. From a modern evolutionary perspective, however, this is no longer enough.

Evolutionary thinking has, of course, already become deeply embedded in the field of psychology, and uncounted studies, papers, and theoretical counter-arguments have looked to use this to improve upon Maslow’s hierarchy. Last fall, Alice Andrews — a professor of psychology and evolutionary studies — shared a very thought provoking “work-in-progress” (her words) on this Sacred Naturalism site, which offered an update to Maslow that she called “evolutionary well-being.” In that post, Andrews also made note of a particularly important 2010 paper from Kenrick et al. titled “Renovating the Pyramid of Needs: Contemporary Extensions Built Upon Ancient Foundations,” which proposed an updated and revised hierarchy of needs based on “theoretical and empirical developments at the interface of evolutionary biology, anthropology, and psychology.” Both of these make for very insightful reading about the human condition. Andrews and Kenrick bring in deep understandings of modern evolutionary findings, and they seek to include issues of social or ecological concern in their discussions of the human psyche. Kenrick goes so far as to put “parenting” on the top of his pyramid of needs in an attempt to make evolutionary survival and reproduction of paramount importance. I think we can take these explorations further, however, in light of two additional evolutionary considerations.

The first is that for a species governed by gene-culture co-evolution, the reproduction and adaptation of memes is surely important too. Who did more for the survival of our species — Aristotle, or one of his neighbors who hypothetically managed to sire 13 children? Procuring food, water, and shelter, and expending resources on reproduction (by at least someof us) may be necessary ingredients for human genes to survive in the short term, but it takes wise and strategic cultural memes to generate robust and enjoyable survival over the long haul. If you agree that Aristotle did more for this than his fecund neighbor might have, then there must be a higher, more governing goal for humans than parenting. That leads to the second point to consider with these hierarchies: the fact that they mostly attempt to depict the needs of all homo sapiensin one single diagram, as if one person could or should do everything on them. This pictorial limitation hampers the much broader perspective — both sociologically and ecologically — that is not only available, but is in fact necessary, as I will describe below.

Redrawing the Hierarchy

Before attempting to sketch in the elements of this broader perspective, it proves helpful to consider the differences between the various hierarchies for individuals in order to see if there is something universal that might be used to harmonize and extend them. First off, what shape actually works best for illuminating this discussion? Maslow used a pyramid, but this seems to imply that the base needs must always remain more largely fulfilled than the higher ones. These base needs are certainly necessary, but an overemphasis on them leads to a shallow existence. Maslow also said that it was only typical to have lesser fulfillment at each progressive level. But this was not, unlike the pyramids at Giza, set in stone. In fact, if all is going very well, Maslow acknowledged that most of a person’s efforts could be aimed towards their higher goals. People often ignore hunger and even the need for social contact when they are preoccupied with their most important intellectual pursuits. Kenrick drew overlapping triangles to show this interplay. Andrews opted for a simple table of needs for goals; her lack of fixed architecture allows her levels to exist freely and overlap in any amount for their relative importance. During our most self-actualized moments, though, we might feel like Maslow’s pyramid should be flipped upside down.

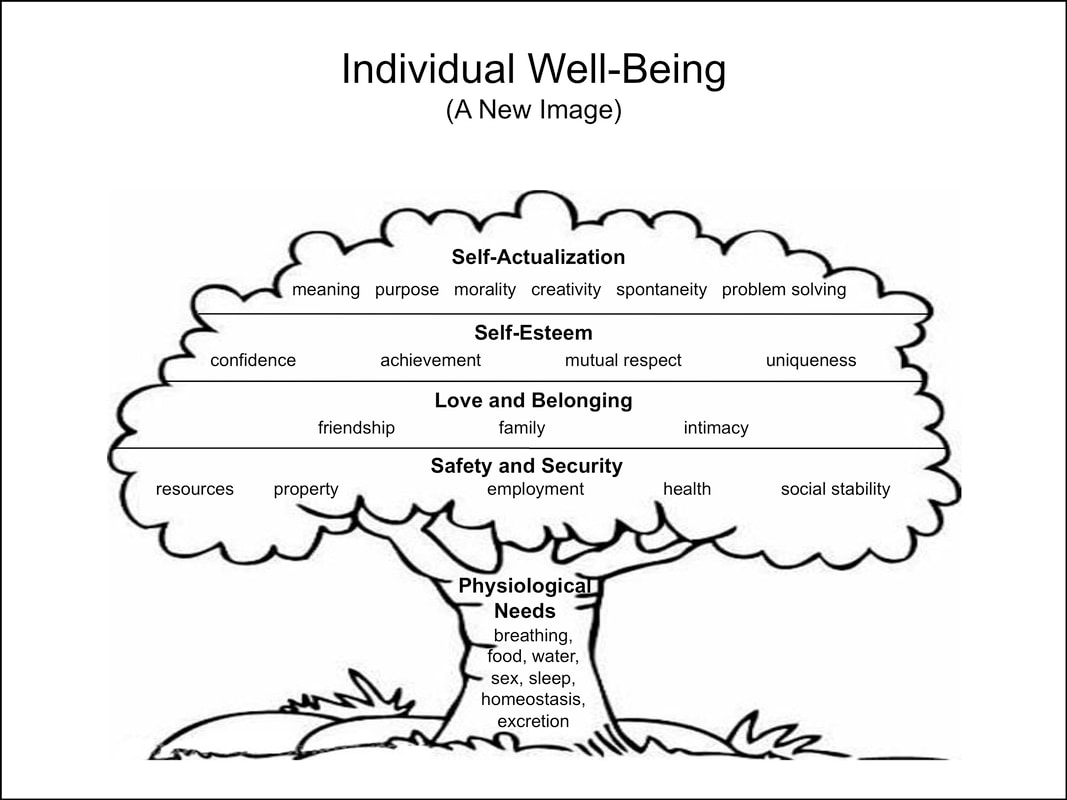

This is what it actually feels like when all of the higher-order needs are met. It's as if the physiological body fades away and only the meaning or purpose of the mind is present. Of course, there is a reason pyramids aren’t built upside-down; they would fall right over. Similarly, we don't want to commit a dualistic error with the mind-body problem and think that the mind actually can float away. Our highest selves must be grounded and supported by a strong and stable body, even if that part of us can be overlooked from time to time. Therefore, I would like to propose a new, albeit familiar, model. One that does not overemphasize the base, nor attempt to float away at the top until the whole thing is at risk of falling over.

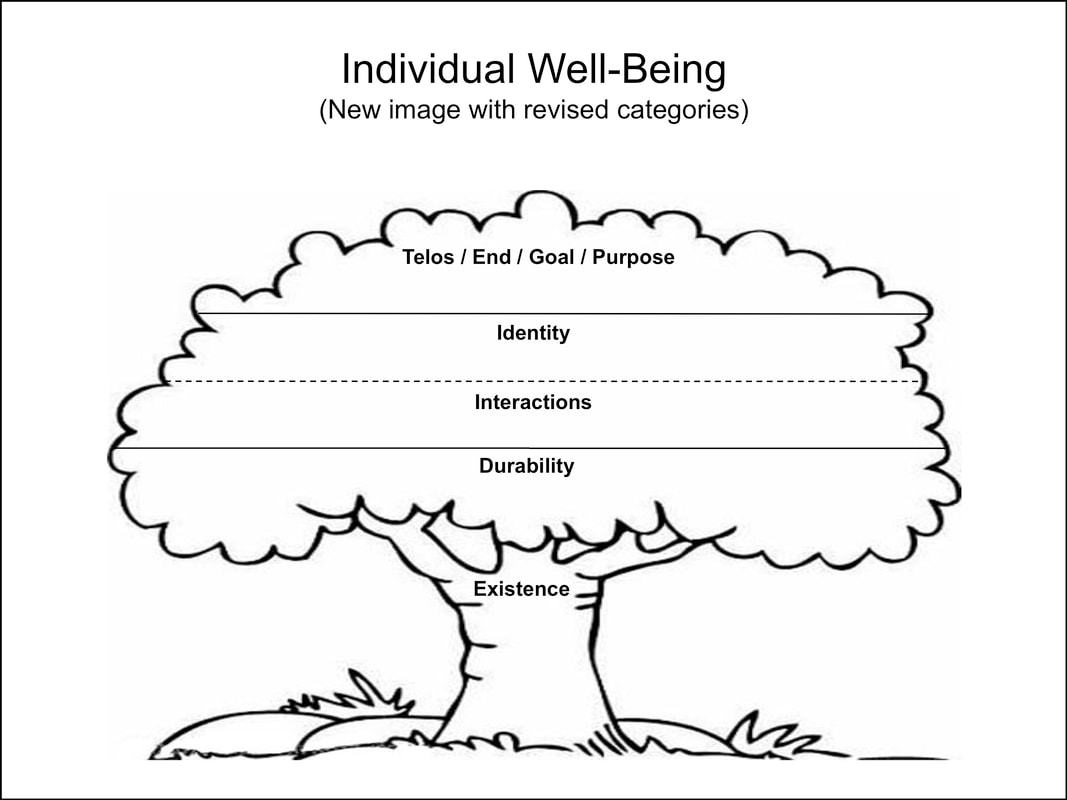

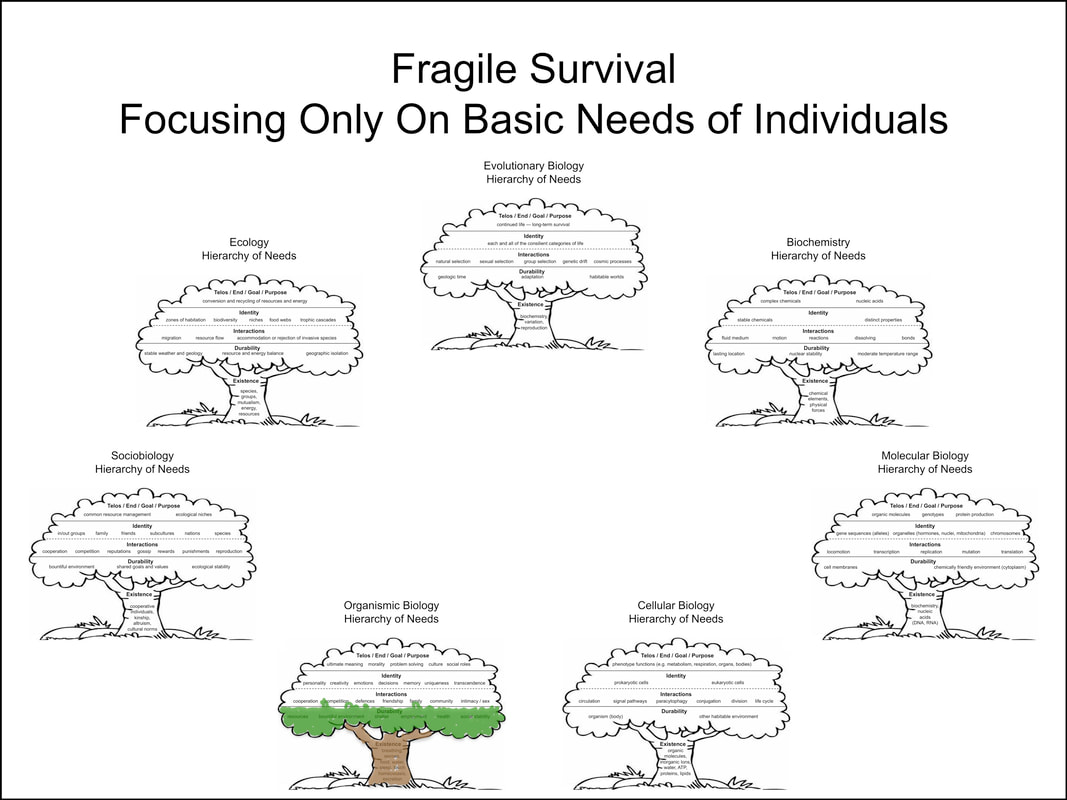

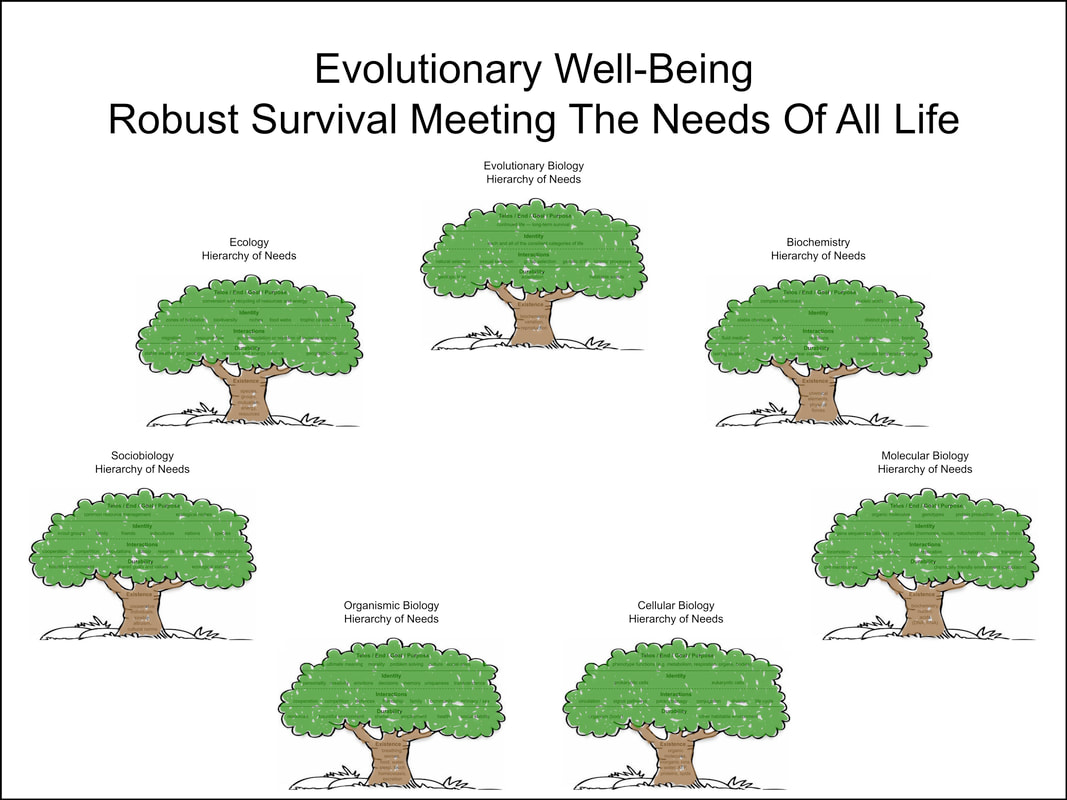

The humble and ancient tree; this is a symbol which provides a host of helpful metaphors. Base physiological needs form the sturdy trunk that funnels nutrients from below and allows our other aspirations to gradually stretch skyward. The second-level needs for safety and security form a protective canopy under which we might take shelter or nourish others. The middle layers could grow wildly or be cultivated in an infinite variety of shapes. And the highest level seeks energy from above to provide direction for the whole entity. This is now a metaphorical image we could use to examine a much broader hierarchy of needs. But before we do that, the names of the five levels have to be reconsidered because Maslow’s categories are infused with concepts that are reserved for human individuals. Kenrick and Andrews proposed other categories of needs, but they too (as professional psychologists) were focused on the evolutionary concerns of individuals. It would be helpful, however, to find something that could be applied not only to humans, but to all forms of life.

Making the Hierarchy Universal

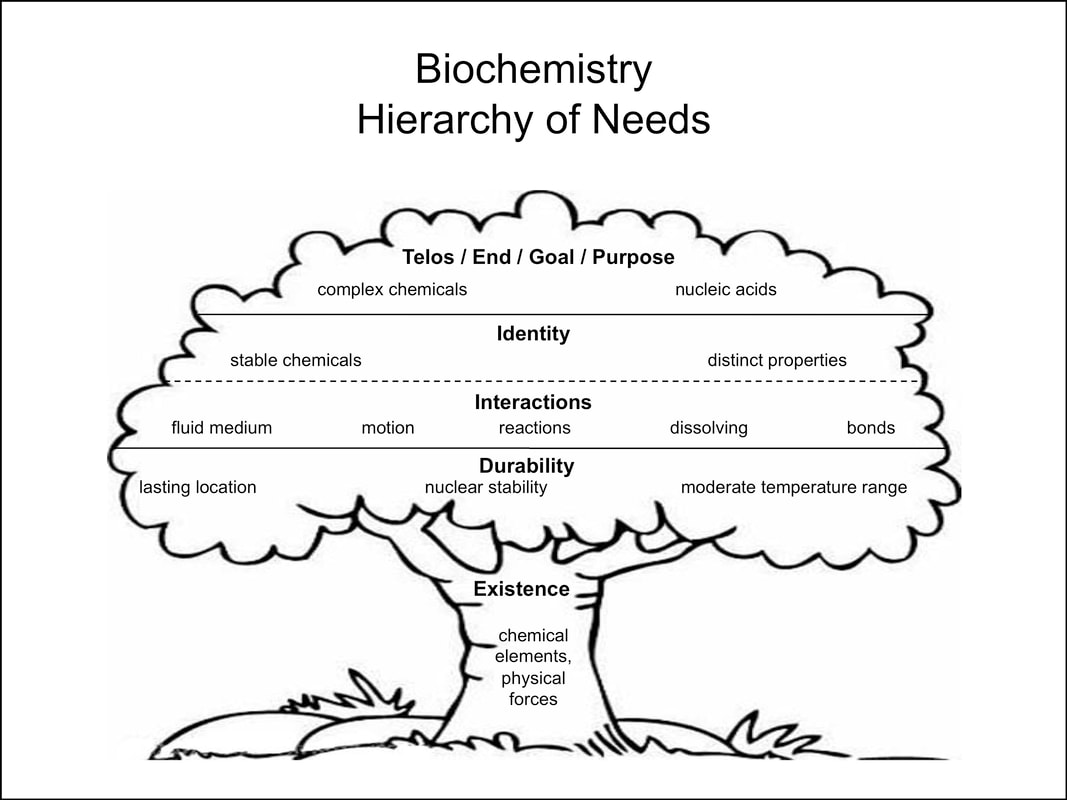

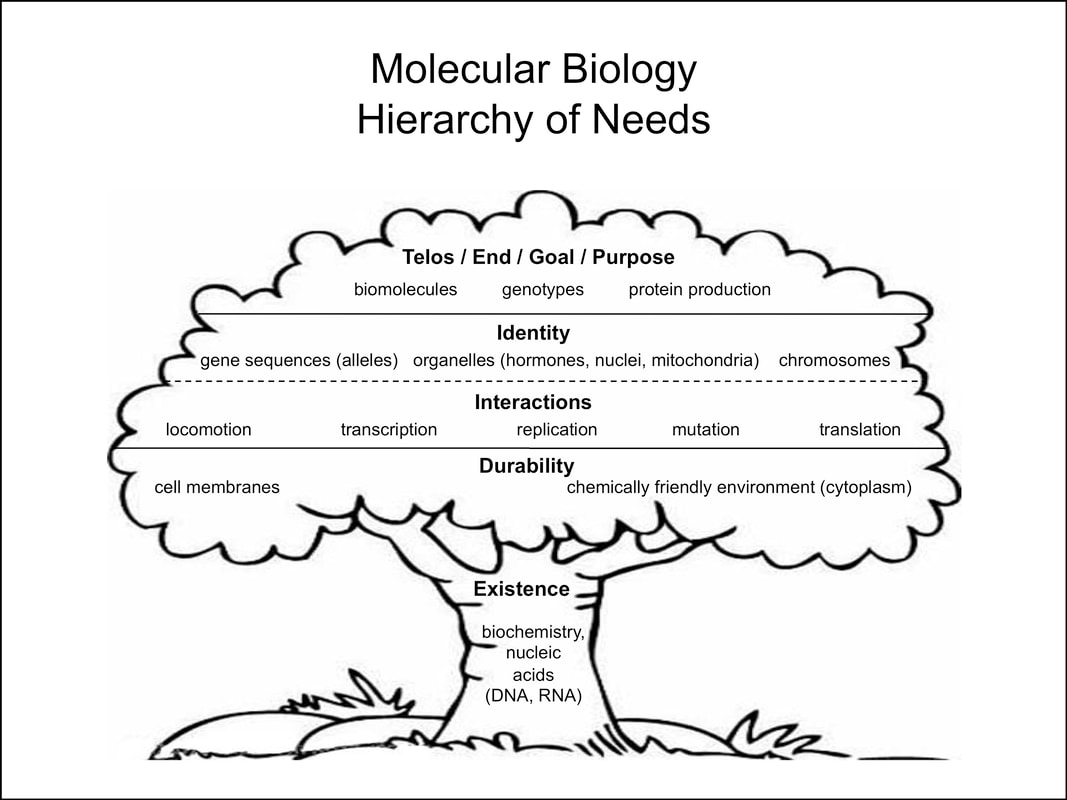

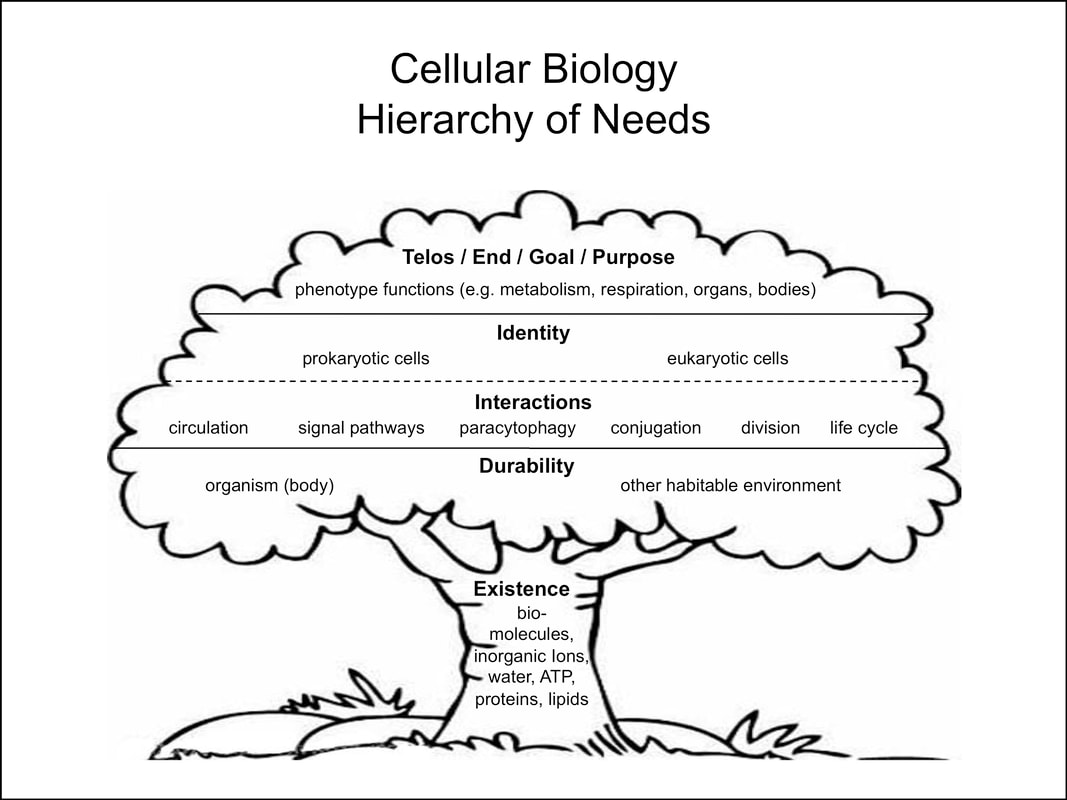

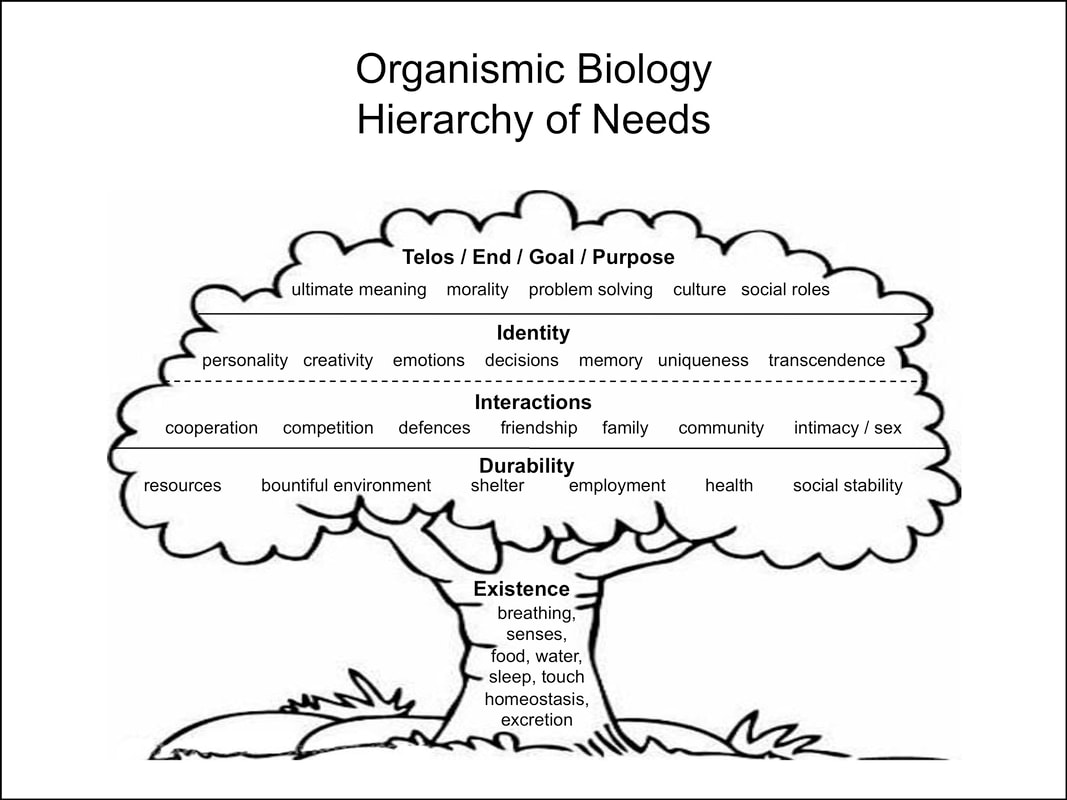

The philosopher Dan Dennett called evolution a universal acid because “it eats through just about every traditional concept, and leaves in its wake a revolutionized world-view, with most of the old landmarks still recognizable, but transformed in fundamental ways.” Similarly, the evolutionary perspective of our diverse and ever-changing web of life transforms Maslow’s hierarchy. Starting at the bottom of the pyramid—or tree now—we see that the “physiological” needs of the human are merely the brute ingredients necessary for “existence” that any form of life might have. In order for that existence to survive through time, the second level needs for “safety and security” can be understood as promoting “durability” in living things. The third tier requirements for “love and belonging” are necessary outcomes from the unavoidable “interactions” that take place in our deeply interconnected biome of Earth. The “self-esteem” needs of individuals could be seen merely as ways for organisms to carve out a useful “identity” within the chaos of competition and cooperation that characterizes the struggle for survival. And finally, the “self-actualization” that Maslow struggled to define (and which Kenrick and Andrews discarded or subsumed elsewhere), could be seen as the end, goal, or purpose that an individual takes on so that they may (consciously or unconsciously) have an ultimate arbiter for the choices that have to be made during their lifetime. This is something Aristotle called “telos.” Putting this all together, we may then change Maslow’s hierarchical pyramid of human needs into the following multi-layered tree for any individual life:

Making the Hierarchy Universal

The philosopher Dan Dennett called evolution a universal acid because “it eats through just about every traditional concept, and leaves in its wake a revolutionized world-view, with most of the old landmarks still recognizable, but transformed in fundamental ways.” Similarly, the evolutionary perspective of our diverse and ever-changing web of life transforms Maslow’s hierarchy. Starting at the bottom of the pyramid—or tree now—we see that the “physiological” needs of the human are merely the brute ingredients necessary for “existence” that any form of life might have. In order for that existence to survive through time, the second level needs for “safety and security” can be understood as promoting “durability” in living things. The third tier requirements for “love and belonging” are necessary outcomes from the unavoidable “interactions” that take place in our deeply interconnected biome of Earth. The “self-esteem” needs of individuals could be seen merely as ways for organisms to carve out a useful “identity” within the chaos of competition and cooperation that characterizes the struggle for survival. And finally, the “self-actualization” that Maslow struggled to define (and which Kenrick and Andrews discarded or subsumed elsewhere), could be seen as the end, goal, or purpose that an individual takes on so that they may (consciously or unconsciously) have an ultimate arbiter for the choices that have to be made during their lifetime. This is something Aristotle called “telos.” Putting this all together, we may then change Maslow’s hierarchical pyramid of human needs into the following multi-layered tree for any individual life:

I’ve removed the details from each category in this tree since we will reapply them later in several new areas. Notice that the third and fourth levels influence each other in an unavoidably bi-directional fashion. All living things need to interact with other living things, and it is only through these interactions that they are thusly defined into an identity. That is why the line between levels 3 and 4 is dashed. You could flip levels 3 and 4, and I wouldn't protest, but I'll stick with this order to hew closer to Maslow. This will also make existentialists happy since the existence of interactions with the environment precedes the essence of an identity. Now, we are finally ready to extend this model for well-being from human individuals out to the wider perspective of others. We can see this single tree, but what about the forest? How do we see the beautiful wholeness described in Jeffers’ poem at the top of this article?

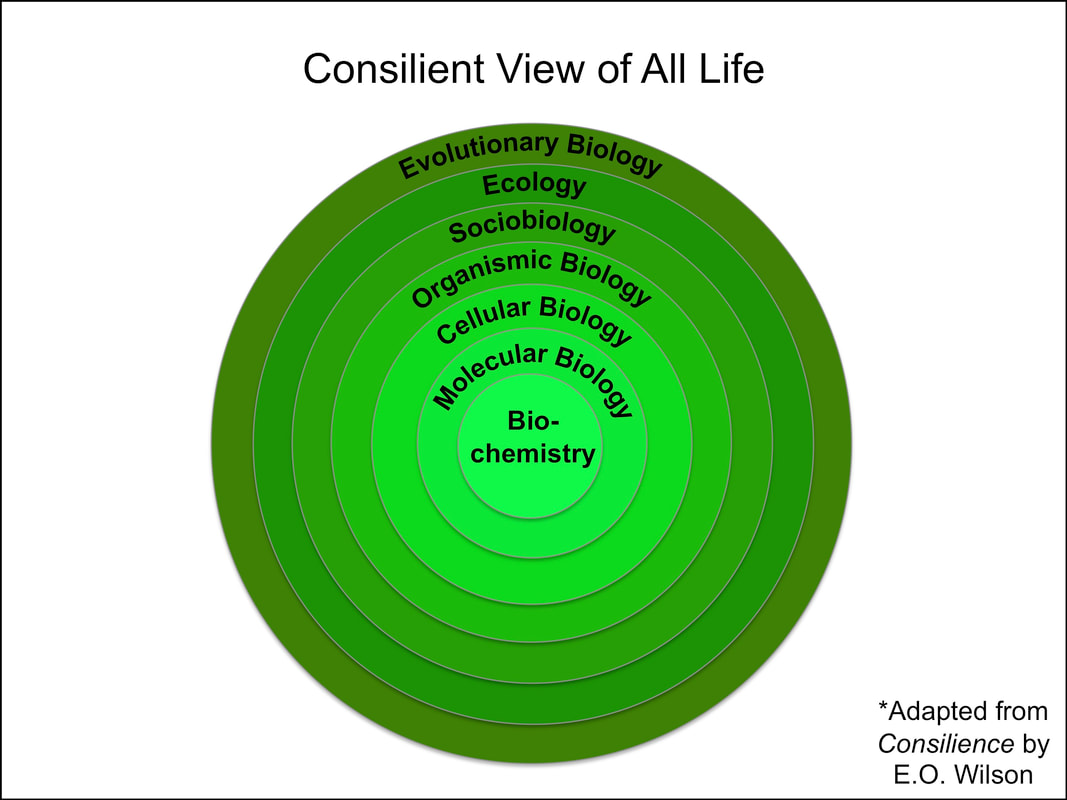

Our Hierarchy is Not Alone

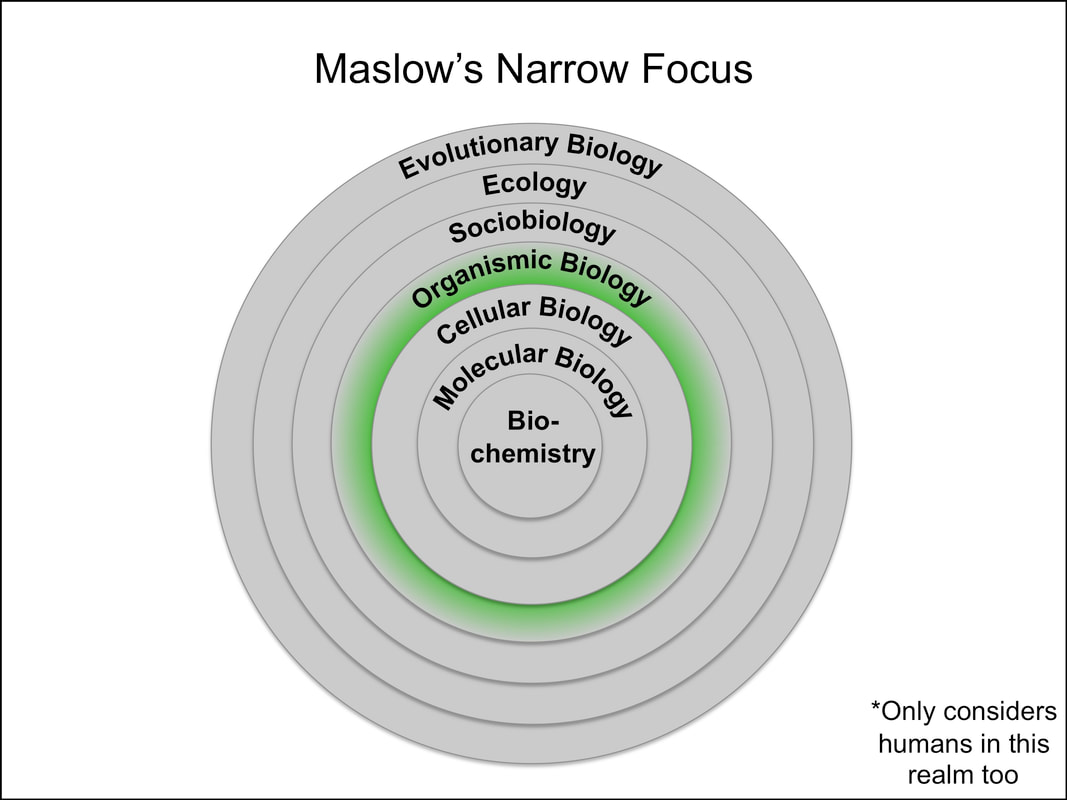

Life is, of course, far more than the separate interests of individuals. There is interplay up and down the entire web of interconnected life, and our evolutionary history shows that everything in this web is all related to one another too. But the specialization of academic fields sometimes makes this hard to see. As I’ve mentioned in previous work, the biologist E.O. Wilson published the book Consilience in 1998 in which he complained about this general splintering of knowledge that kept scientists in the dark about facts that had already been discovered in other fields. In particular, he bemoaned the divide in his own area of specialty and noted the means by which they could be united. He wrote that the “conception of scale is the means by which the biological sciences have become consilient during the past fifty years. According to the magnitude of time and space adopted for analysis, the basic divisions of biology” can therefore be pictured like this:

Our Hierarchy is Not Alone

Life is, of course, far more than the separate interests of individuals. There is interplay up and down the entire web of interconnected life, and our evolutionary history shows that everything in this web is all related to one another too. But the specialization of academic fields sometimes makes this hard to see. As I’ve mentioned in previous work, the biologist E.O. Wilson published the book Consilience in 1998 in which he complained about this general splintering of knowledge that kept scientists in the dark about facts that had already been discovered in other fields. In particular, he bemoaned the divide in his own area of specialty and noted the means by which they could be united. He wrote that the “conception of scale is the means by which the biological sciences have become consilient during the past fifty years. According to the magnitude of time and space adopted for analysis, the basic divisions of biology” can therefore be pictured like this:

This simple diagram is actually an astonishingly broad vision of all of the life that has ever existed. These seven categories describe the study of life in totality, from the smallest atomic building blocks, to the billions of years of life history that they have constructed. For all the numerous and very important findings that Maslow and other psychologists have discussed and discovered, they still only comprise a tiny sliver of this view.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with such focus. That’s how we collectively develop true expertise throughout each of the vast possibilities for domains of knowledge. But I suspect Maslow was especially narrow because he overreacted to the behaviorists of his day who tried to use their own expertise in the study of rats to declare broader principles for human psychology. In his seminal paper, Maslow wrote:

“There is no reason whatsoever why we should start with animals in order to study human motivation. The logic or rather illogic behind this general fallacy of 'pseudo-simplicity' has been exposed often enough by philosophers and logicians as well as by scientists in each of the various fields. It is no more necessary to study animals before one can study man than it is to study mathematics before one can study geology or psychology or biology.”

Today we recognize that this is a big flaw. All sciences require the mathematical analyses of data. And the study of nonhuman animals can yield precious clues about the development of environmental responses that exist across the entire continuum of life. Maslow and other psychologists say that individual humans have a need to care for their kin, but what does that really mean once science teaches us that all of life is our kin? Rather than just trying to understand and meet the hierarchy of needs for our fellow human individuals, we could collectively spend much more time considering such details for each realm of E.O. Wilson’s consilient view of life. It’s beyond the scope of this essay to justify each and every detail in a hierarchy of needs for every sub-field of biology (and these details would really need to be refined by experts in these fields anyway), but stepping quickly through such hierarchies shows us that it is not only possible, but further research here would likely be illuminating. Let’s begin that journey looking at smallest details of life.

“There is no reason whatsoever why we should start with animals in order to study human motivation. The logic or rather illogic behind this general fallacy of 'pseudo-simplicity' has been exposed often enough by philosophers and logicians as well as by scientists in each of the various fields. It is no more necessary to study animals before one can study man than it is to study mathematics before one can study geology or psychology or biology.”

Today we recognize that this is a big flaw. All sciences require the mathematical analyses of data. And the study of nonhuman animals can yield precious clues about the development of environmental responses that exist across the entire continuum of life. Maslow and other psychologists say that individual humans have a need to care for their kin, but what does that really mean once science teaches us that all of life is our kin? Rather than just trying to understand and meet the hierarchy of needs for our fellow human individuals, we could collectively spend much more time considering such details for each realm of E.O. Wilson’s consilient view of life. It’s beyond the scope of this essay to justify each and every detail in a hierarchy of needs for every sub-field of biology (and these details would really need to be refined by experts in these fields anyway), but stepping quickly through such hierarchies shows us that it is not only possible, but further research here would likely be illuminating. Let’s begin that journey looking at smallest details of life.

We start with the objective, scientific view of the “needs” of biochemistry. In these lower levels of biology, there are only reactions; there are no choices or free will to be had. Thus, we are not in the realm of psychology yet where discussions of needs lead to subjective personal motivations. But since our own psychological needs ultimately do depend on these lower biological needs, we really must consider them and nourish them where necessary. We don’t actually know the true origins of life (aka abiogenesis), so we don’t know everything that is needed for biochemistry to occur, but we have learned quite a bit about this subject by studying extremophiles as well as the barren foreign planets where even those forms of life do not exist. If you follow the wicking action up the tree, you see that biochemistry must start with chemical elements and the fundamental forces of the universe (i.e. gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces). These chemicals must have a durable location that does not continually tear them apart. They must move around in some kind of fluid medium in order to react and bond with one another. Eventually, stable chemicals with distinct properties arose that led to the origin of complex chemicals and nucleic acids—the building blocks of life as we know it. Could biochemistry have “preferred” to end with simple rather than complex chemicals? Yes. But in evolutionary systems, this is not what survives, thrives, and progresses. The objective telos of biochemistry is derived from the role it plays in the larger complex web of life. Keep this principle in mind as we move forward.

Next, we take the outputs of biochemistry and see what is required to combine them into more complex components of life—molecular biology. I won’t keep stepping through all the details here, but the same can then be done through the next level of biology too, where cells are created.

Note that for these second and third levels of biology, their durability is dependent on the next level up. Complex biomolecules require cells to survive and thrive, and complex eukaryotic cells require organisms with bodies to provide their environment for life. Once we reach organisms, this principle continues, but we cross a major threshold to the realm where Maslow et al. are waiting for us.

Organismic biology is the only realm concerned with individuals. Before this, we looked at components. After this, we’ll look at collectives. Could organisms prefer an end goal of free and isolated individuals? Yes. But remember the earlier principle we established. This is not what survives, thrives, and progresses in evolutionary systems. Individuals survive better when they form the basis for relatively stable sociobiological groups that continue to adapt to their environments.

This is the first realm where the collection of biochemical reactions has finally become complex enough where actions of one group within the organism can override those of another, either through force, conditioning, or learning. This internal struggle results in choices being made (this may be the basis for what we humans call free will), which brings the entire organism into a new environmental location or state of being, thus setting off a whole new set of biochemical reactions. The successful outcomes from trials and errors of these choices are what get passed down through the generations via instinct or eventually culture in those organisms that possess it.

Looking at humans this way, we see a few changes made to Maslow’s hierarchy and other similar efforts. Sex is moved from a “physiological need” to an “interaction.” Creativity and spontaneity are moved from “self-actualization” to items within “identity.” Mate acquisition, mate retention, and parenting are all subsumed from the top of Kenrick’s triangles into family and intimacy “interactions.” Transcendence is an experience of getting outside of the self. It is therefore one way to help redefine the “identity” of the individual and allow it to better see all the interactions that it is a part of. As with all of the other realms of biology, these interactions and identities go on to form the components of the next level. In this case, that is sociobiology, where some animals, including us humans, create societies of various sizes and compositions.

This is the first realm where the collection of biochemical reactions has finally become complex enough where actions of one group within the organism can override those of another, either through force, conditioning, or learning. This internal struggle results in choices being made (this may be the basis for what we humans call free will), which brings the entire organism into a new environmental location or state of being, thus setting off a whole new set of biochemical reactions. The successful outcomes from trials and errors of these choices are what get passed down through the generations via instinct or eventually culture in those organisms that possess it.

Looking at humans this way, we see a few changes made to Maslow’s hierarchy and other similar efforts. Sex is moved from a “physiological need” to an “interaction.” Creativity and spontaneity are moved from “self-actualization” to items within “identity.” Mate acquisition, mate retention, and parenting are all subsumed from the top of Kenrick’s triangles into family and intimacy “interactions.” Transcendence is an experience of getting outside of the self. It is therefore one way to help redefine the “identity” of the individual and allow it to better see all the interactions that it is a part of. As with all of the other realms of biology, these interactions and identities go on to form the components of the next level. In this case, that is sociobiology, where some animals, including us humans, create societies of various sizes and compositions.

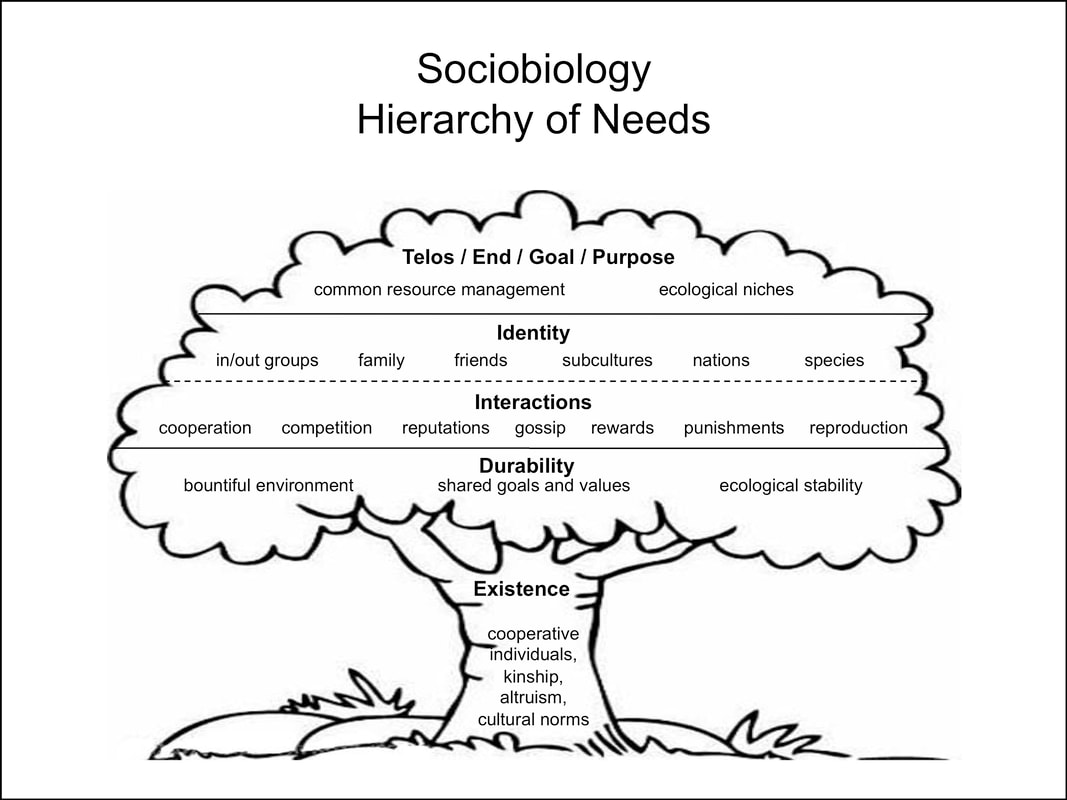

It’s important to recognize that societies are not super-organisms; there is no extra physical information governing their behavior beyond that contained within individual organisms. However, societies are composed of individuals who have been shaped by evolution / instinct / culture to navigate any necessary tradeoffs between individual needs and any larger group needs. This explains the important role at the top of this tree for the successful management of common resources by such groups, which is the subject of Elinor Ostrom’s Nobel-Prize-winning research. And as before, societies survive best when they are protected by strong and thriving biological realms above them, which in this case are ecosystems.

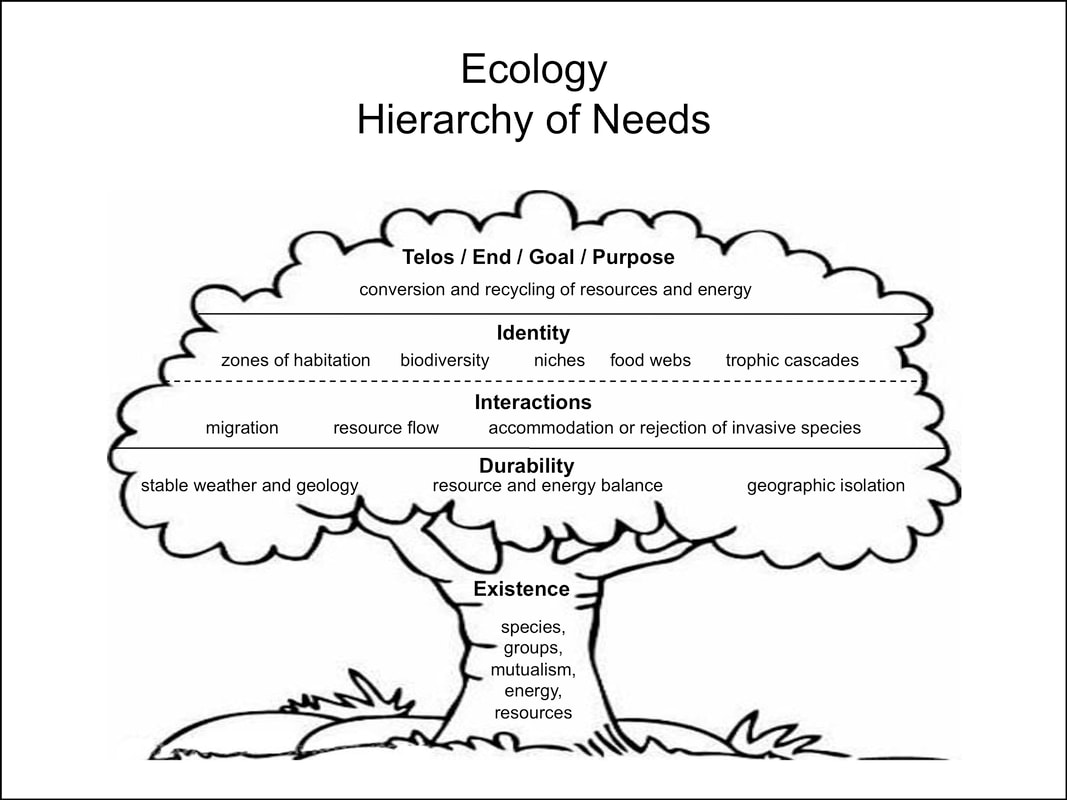

From the science of ecology, we are now learning the complex ways in which ecosystems persist over time by being stable enough yet interactive enough to provide time and resources for the evolution of their mutually reinforcing species to occur. Could there be something beyond ecosystems? Exobiology is the study of the possibility of life on other planets or in space, and so one day this field could play a role in the evolution of life as we know it. But for now, it does not. And so we finally arrive at our largest and longest view of life.

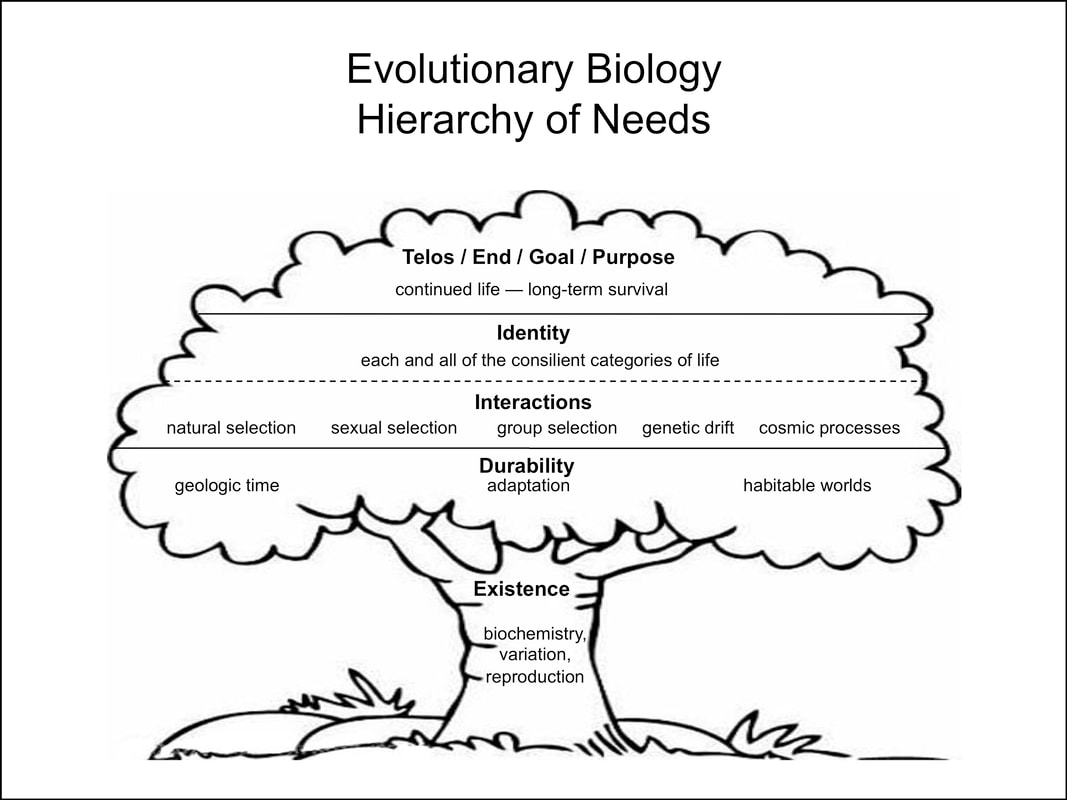

With this view of life, we are brought back to the basics of the need for biochemistry, reproduction, and variation to occur in habitable worlds over geologically long timelines at a pace that allows for adaptation. Various forms of selection have produced each and every one of the forms of life in all of the consilient categories that exist. And as far as we can tell, there is no other purpose for life in this universe other than its continued and enjoyed survival over the long term.

What These Evolutionary Hierarchies Show

The most important takeaway from this quick pass through the collection of hierarchies is the fact that they are all related. Each level of biology requires a healthy and stable lower level to provide the ingredients for its existence. Each level also needs a healthy and stable level above it to provide a durable habitat for its existence. And the top-most level of evolutionary biology can only kick off (as far as we know from the history of Earth) after the formation of biochemistry in the lowest level. In other words, no matter how much you focus on one seemingly individual tree, it is actually part of an interwoven forest of life.

This broad perspective is not a luxury for the philosophically minded alone. As I said at the top of this essay, it is a necessity. If we are to consider needs at all, we must enlarge our circle of concern as far as it will go. If I held that the flourishing of Ed Gibney was the absolute highest priority, others would find me selfish and stop working with me. They might even imprison me depending on my acts of callous selfishness. Only a lack of power and opportunity would stop me from acting for myself by exploiting others. If, instead, the flourishing of my family were the highest priority, I would provoke feuds with clans or mafias around me. If the flourishing of my community were the highest priority, ideological crusades and genocides would be eventual outcomes after intractable disagreements. If the flourishing of my nation were the highest priority, wars would be the result. If the flourishing of my species were the highest priority, we would commit ecocide without a second thought. If my ecosystem were the highest priority, our invasive species would produce monocultures with little resilience in the face of change. It’s only when our absolute highest priorities are concerned with the evolution of life in general that we can find ways for all of life to flourish together and ensure its long-term survival.

Ever since Darwin's revolutionary idea came along, science has rather rapidly filled in the details of this interrelatedness. Yet much of philosophy, law, politics, and psychology are still focused on the realm of the individual, arguing even over how best to support any flourishing there. That, however, is an impoverished view.

What These Evolutionary Hierarchies Show

The most important takeaway from this quick pass through the collection of hierarchies is the fact that they are all related. Each level of biology requires a healthy and stable lower level to provide the ingredients for its existence. Each level also needs a healthy and stable level above it to provide a durable habitat for its existence. And the top-most level of evolutionary biology can only kick off (as far as we know from the history of Earth) after the formation of biochemistry in the lowest level. In other words, no matter how much you focus on one seemingly individual tree, it is actually part of an interwoven forest of life.

This broad perspective is not a luxury for the philosophically minded alone. As I said at the top of this essay, it is a necessity. If we are to consider needs at all, we must enlarge our circle of concern as far as it will go. If I held that the flourishing of Ed Gibney was the absolute highest priority, others would find me selfish and stop working with me. They might even imprison me depending on my acts of callous selfishness. Only a lack of power and opportunity would stop me from acting for myself by exploiting others. If, instead, the flourishing of my family were the highest priority, I would provoke feuds with clans or mafias around me. If the flourishing of my community were the highest priority, ideological crusades and genocides would be eventual outcomes after intractable disagreements. If the flourishing of my nation were the highest priority, wars would be the result. If the flourishing of my species were the highest priority, we would commit ecocide without a second thought. If my ecosystem were the highest priority, our invasive species would produce monocultures with little resilience in the face of change. It’s only when our absolute highest priorities are concerned with the evolution of life in general that we can find ways for all of life to flourish together and ensure its long-term survival.

Ever since Darwin's revolutionary idea came along, science has rather rapidly filled in the details of this interrelatedness. Yet much of philosophy, law, politics, and psychology are still focused on the realm of the individual, arguing even over how best to support any flourishing there. That, however, is an impoverished view.

This view has infected far too much of society. It is the view of the me generation (and their offspring, the me me me generation), for whom Maslow’s “self-actualization” actually became “a cultural aspiration to which young people supposedly ascribed higher importance than social responsibility.” It is also the view of corporations whose executives are legally bound and educationally trained to see that the only purpose of a public company is to make money. It is the view of politicians who overwhelmingly govern and are elected to create high growth in GDP because “it’s the economy, stupid.” Even the United Nation’s Human Development Index is only a composite statistic of life expectancy, education, and per capita income indicators for individuals. This is indeed “The Century of the Self.”

Paying attention, however, to only the partial fulfillment of individuals’ needs—or even to all of them, but in isolation from the rest of life—risks a very fragile existence. Granting unrestrained freedom to narrow-minded individuals will unquestionably lead to more tragedies of the commons. And those commons are, we now know, our supportive kin. They are required for the ecological and social stability needed to support our own individual needs, which go on to support other forms of life, all the way down. Not only are these components and collectives of life hurt by our narrow view, but this actually hurts the individual too. As Joanna Macy, author and scholar of deep ecology says:

“I am convinced that this loss of certainty that there will be a future is the pivotal psychological reality of our time. The fact that it is not talked about very much makes it all the more pivotal, because nothing is more preoccupying or energy-draining than that which we repress.”

In fact, the field of ecopsychology has sprung up to treat such ills, and its practitioners argue that we cannot be whole and at peace until we do so. As ecopsychologist Andy Fisher explains,

“The human psyche emerged from this earthly world and remains tied to it. The delusion that we can break this tie—that we can forget our kinship, our intimate relations, with plants, animals, and soil, that we can dissociate ourselves from bodily and ecological rhythms, imposing a mechanical order of time instead, that we can do all these life-denying things without consequence to the integrity of both our minds and the rest of earthly creation—this is the serious problem ecopsychology addresses.”

And so, it is incumbent upon us, for individual and collective reasons, to not only understand Maslow and other psychologists’ hierarchies of human needs, but we must also expand these hierarchies and adapt them to portray a wider and fully evolutionary view as well. As Darwin himself said, there is grandeur in this view of life.

Paying attention, however, to only the partial fulfillment of individuals’ needs—or even to all of them, but in isolation from the rest of life—risks a very fragile existence. Granting unrestrained freedom to narrow-minded individuals will unquestionably lead to more tragedies of the commons. And those commons are, we now know, our supportive kin. They are required for the ecological and social stability needed to support our own individual needs, which go on to support other forms of life, all the way down. Not only are these components and collectives of life hurt by our narrow view, but this actually hurts the individual too. As Joanna Macy, author and scholar of deep ecology says:

“I am convinced that this loss of certainty that there will be a future is the pivotal psychological reality of our time. The fact that it is not talked about very much makes it all the more pivotal, because nothing is more preoccupying or energy-draining than that which we repress.”

In fact, the field of ecopsychology has sprung up to treat such ills, and its practitioners argue that we cannot be whole and at peace until we do so. As ecopsychologist Andy Fisher explains,

“The human psyche emerged from this earthly world and remains tied to it. The delusion that we can break this tie—that we can forget our kinship, our intimate relations, with plants, animals, and soil, that we can dissociate ourselves from bodily and ecological rhythms, imposing a mechanical order of time instead, that we can do all these life-denying things without consequence to the integrity of both our minds and the rest of earthly creation—this is the serious problem ecopsychology addresses.”

And so, it is incumbent upon us, for individual and collective reasons, to not only understand Maslow and other psychologists’ hierarchies of human needs, but we must also expand these hierarchies and adapt them to portray a wider and fully evolutionary view as well. As Darwin himself said, there is grandeur in this view of life.

----------------------------------

Ed Gibney is a writer and evolutionary philosopher who blogs about his beliefs and the fiction it inspires at evphil.com.

Subscribe to Help Shape This Evolution

© 2012 Ed Gibney