--------------------------------------------------

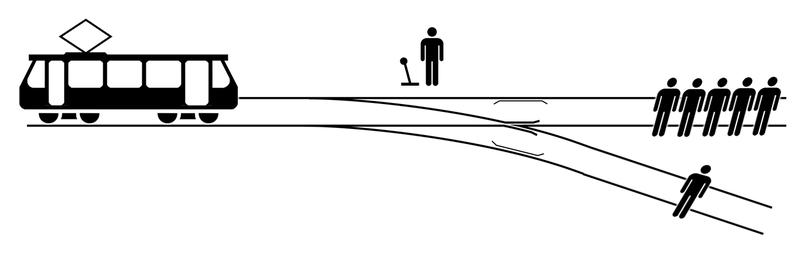

Greg has just one minute to make an agonising choice. A runaway train is hurtling down the track towards the junction where he is standing. Further down the line, too far away for him to reach, forty men are working in a tunnel. If the train reaches them, it is certain to kill many of them.

Greg can't stop the train. But he can pull the lever that will divert it down another track. Further down this line, in another tunnel, only five men are working. The death toll is bound to be smaller.

But if Greg pulls the lever, he is deliberately choosing to bring death to this gang of five. If he leaves it alone, it will not be him who causes deaths among the forty. He must bring about the deaths of a few people, or allow even more to die. But isn't it worse to kill people than it is simply to let them die?

The rails are humming, the engine noises getting louder. Greg has only seconds to make his choice. To kill or let die?

Source: "The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect" by Philippa Foot, 1967

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 265.

---------------------------------------------------

Seems awfully straightforward. Greg is faced with a choice of killing 5 people or 40 people. He therefore ought to kill fewer people. You probably didn't even need your full minute to make that choice. But as the source of this thought experiment Philippa Foot said:

You ask a philosopher a question and after he or she has talked for a bit, you don't understand your question any more.

How true. And if you need yet another example of that, go ahead and read Foot's original paper which this thought experiment is based upon. As may be apparent from the title, it's actually an exploration of the subtle arguments used in the debate about abortion, such as the doctrine of double effect and the acts vs. omissions doctrine. I've already covered these topics in my responses to thought experiments 29: Life Dependency (re: abortion), 53: Double Trouble (re: double effect), and 71: Life Support (re: acts/omissions). I toyed with rehashing all of those debates again here, but that would put me at great risk of living up to Foot's caution about philosophers answering questions. Instead, I thought it would be much better to simply point out that the "kill" or "let die" choice isn't a meaningful one here. "Acting" or "not acting" are both options we must choose from, and one is not necessarily less implicative than the other. I happened to pick up a book this week by Jean-Paul Sartre (Existentialism and Humanism), which had this quote in one of its reviews that shows what I mean:

Whatever your choice you will nonetheless be making a choice even if that choice is not to make a choice. Or as Sartre would put it, in a far more philosophical manner, you can always choose but you must know that even if you do not choose that would still be a choice. For what is not possible is not to choose.

So the choice is the thing we judge for its moral implications. And the choice for the thought experiment above seems obvious. But what if we vary the situation slightly? Can that teach us more about the moral judgments we are making here?

Before I go through the standard variations of the trolley problem, let's remember the moral rules I've asserted for evolutionary philosophy. I believe the ultimate judge for the goodness or badness of actions is whether or not they lead to the survival of life in general over the long term of evolutionary timeframes. And contrary to the academic divisions of moral philosophy, we must look at the whole picture to evaluate any such questions. As I described in my response to thought experiment 60:

Deontological moral rules are not sufficient. Consequentialism shows that results matter too. And virtue ethics says intentions also count. Together, these three schools of thought make up the three main camps of moral philosophy. However, as is often the case with thorny philosophical issues, the best position on morality isn't an "either/or" decision from among these three choices, it's an "all/and" decision which considers the three of them. For any morally-considered human behavior, there is an intention, an action, and a result. That's the way an event is described prior to, during, and after it occurs. It's the way the past, present, and future are bound together by causality yet allowed to be looked at separately across time. Virtue ethics concerns itself with the intention. Deontology focuses on the action. Consequentialism focuses on the result. But all three may be evaluated individually for moral purposes. ... We can hold all three of these judgments in our head at the same time and use them to guide future decisions accordingly with respect to blame, praise, imitation, or change.

Got it? If we were to apply this to the standard trolley problem as outlined in the thought experiment above, we would see that Greg's virtuous intentions ought to be that fewer people die in this situation. That's the consequence that we are rooting for. So even though his action produces some deaths, that is not a bad action because some deaths were going to occur no matter what.

Now let's explore this further by simply listing some variations discussed in the wikipedia entry on the Trolley Problem. Try to intuit your answers to these as you go along.

- The Fat Man - A trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by putting something very heavy in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you – your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

- The Fat Villain - The same situation as #1, except the fat man standing next to you was the one who tied the five people onto the tracks below. Would you throw that man onto the tracks?

- The Man in the Yard - As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You can divert its path by colliding another trolley into it, but if you do, both will be derailed and go down a hill, and into a yard where a man is sleeping in a hammock. He would be killed. Should you proceed?

- The Transplant - A brilliant transplant surgeon has five patients, each in need of a different organ, each of whom will die without that organ. Unfortunately, there are no organs available to perform any of these five transplant operations. A healthy young traveler, just passing through the city the doctor works in, comes in for a routine checkup. In the course of doing the checkup, the doctor discovers that his organs are compatible with all five of his dying patients. Suppose further that if the young man were to disappear, no one would suspect the doctor. Do you support the morality of the doctor to kill that tourist and provide his healthy organs to those five dying persons and save their lives?

- The Judge - Suppose that a judge is faced with rioters demanding that a culprit be found for a certain crime and threatening otherwise to take their own bloody revenge on a particular section of the community. The real culprit being unknown, the judge sees himself as able to prevent the bloodshed only by framing some innocent person and having him executed. Should she convict the scapegoat?

- Personal Connections - A trolley is hurtling down the track towards 5 people who will certainly die if the train reaches them. You cannot stop the trolley, but you can divert it onto another track where only 1 person will be killed. That person, however, is your daughter. (Or wife, or son, or best friend.) Should you flip the switch so fewer people die?

- Numbers Games - A trolley is hurtling down the track towards 5,000 people who will certainly die if the train reaches them. You cannot stop the trolley, but you can divert it onto another track where only 1 person will be killed. That person is your daughter. (Or wife, or son, or best friend.) Should you flip the switch so fewer people die?

As I said in the opening to this blog post, 90% of people agree that Greg should pull the switch to kill 5 people rather than 40. The data for these other scenarios have been gathered in many different forms, but generally people would be willing to throw one fat villain onto the tracks to stop a train, but not if that fat man were an innocent bystander. Similarly, they wouldn't crash the train if it would then go kill a man just sitting in his yard. Few people think the surgeon or judge should sacrifice innocent people, but intuitions change wildly if personal connections or large numbers enter into the equation. And answers change once people have been exposed to the different manifestations of this problem too, as we see in the results from professional philosophers, 24% of whom basically say "it's complicated." So what can we learn from all of these scenarios?

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from the set of trolly problem problems is that there is no single simple rule that answers them all. Even a seemingly sturdy deontological maxim such as "Kill Less People" just doesn't hold up in all circumstances. The level of certainty about the outcomes changes things. The relative guilt or innocence of the people involved changes the math. Our connections to the people changes the math too, but maybe not so wildly that we would ignore the opportunity to save thousands of other lives.

While pioneering the theory of kin selection, J.B.S. Haldane once joked that he would gladly give up his life for two brothers or eight cousins. It would be nice if we could find something morally equivalent to this, but we can't because Haldane was only talking about concerns with genetic evolution. Human evolution, however, as well as the evolution of other advanced animals, is governed to a greater or lesser extent by a mix of genetic AND cultural traits. Given the practically unknowable value of one unique human to the cultural evolution of our species, we just aren't going to be able to weigh life and death trolley decisions accurately according to some simple rule. In my journal article, I wrote that the end goal of morality may now be known, but...

Is the way forward clear? Are the answers to all of our moral dilemmas suddenly obvious? Hardly. But that’s okay, because any framework for morality that does not account for the friction that has continually accompanied our difficult moral choices is a framework that does not account for reality. We would not have such a long history of questions in this sphere if we did not have an extremely complicated set of competing wants that we all feel and must try to make sense of. But at least now we can see the locations of all those sticking points. All moral dilemmas can be understood as conflicts somewhere along the consilient spectrum of biology.

Our intuitive moral feelings are often in conflict because of the debates that rage within us regarding the self vs. society, or society vs. the environment, or the short-term vs. the long-term, or just the fundamental choices between competition and cooperation. This is what drives the two faces of humankind. We are neither inherently good nor inherently evil – we are capable of both, a flexibility we must have in order to have the power to choose between alternate paths that are right some of the time and wrong some of the time.

These and many other questions of morality still remain to be answered. Knowing these locations and desired outcomes though will help us empirically evaluate our choices wherever it is possible to experiment with them. Good answers will strike the best balance between all the options. Evil answers will get the mix wrong. Most commonly, evil will involve weighting the needs of an individual too heavily in comparison to the needs of other individuals or other groups. But there will also be instances of evil being done to individuals in the name of social or ecological forces that have been overweighted.

These are the tradeoffs that must be addressed correctly by our moral urges if we are to survive. These are the base sources of all our competing wants, which drive all our competing oughts, which our systems of ethics must choose between. By utilizing the comprehensive framework for biology to understand the totality of wants for all forms of life, we come to a clearer understanding of morality, which seeks to satisfy those wants in an optimal manner.

I could go through all the various scenarios of the trolley problem and give theoretical answers to their theoretical setups, but that seems a bit unnecessary once my general attitudes are known. Act to support life, which requires care for the self balanced against care for others. But what do you think? Are there any other lessons to be learned from all of these trolleys running over people? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.