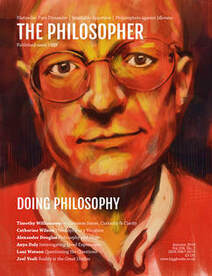

| Hello! I was asked to speak at an event at the end of September to give my thoughts on a book called Doing Philosophy, which was written by Timothy Williamson who is the Wykeham Professor of Logic at the University of Oxford. I was one of four such speakers at the event, where Professor Williamson gave opening remarks, and rebuttals to us as well. This was all set up to be featured in the latest edition of The Philosopher (the official journal of the Philosophical Society of England, and the UK's longest-running public philosophy journal, having started in 1923) and it has now finally been published. Due to changes in the time (and space) constraints at the event (and in the |

Doing Philosophy: Thought Experiments and the Truth About Truth

In preparation for this event, I read through a book on how to give TED talks by Chris Anderson (he’s the owner of TED), and I was stunned to see him bring up the topic of the power of philosophical thought experiments. This seemed like an amazing coincidence to me, but the reason is because Anderson wants his readers to give memorable talks. He quoted the philosopher Dan Dennett who noted that it was thought experiments that have provided the most remarkable passages in the history of philosophy — not formal proofs. Only a very few people can recall the premises and conclusion of some important logical syllogism. But many, many more people will have heard of Plato’s allegory of the cave, or the innocent bystander on the tracks near a runaway trolley, or maybe even the child called Mary who was locked away in her black and white room while she learned “everything there is to know about the colour red.”

Why do we remember these thought experiments? Because they are art. They are stories that evoke strong emotional responses. They have memorable characters who are tied up in some conflict, and we’re not sure how, or even if, they’ll be able to get out of it. But if they are art, why do we get to use them in philosophy? Why do they count for arguments of reason too? As Williamson memorably asks, “How come philosophers get away with just sitting in their armchairs and imagining it all?”

The reason is that our imagination is an incredible tool that has been honed to a fine edge over billions of years of evolution. Evolution is usually characterised as a series of trials and errors, but ones that are done blindly by Mother Nature. And until very recently, that’s how all life on Earth adapted and survived — blindly. But now that we know about this, we humans can conduct those trials and errors with a bit of wise foresight and consciousness. Scientists carefully plan their trials and errors all the time, but there are some places where it’s impossible for scientists to go. As Williamson says:

“Imagination is especially useful when trial and error is too risky. … Imagining is [also] our most basic way of learning about hypothetical possibilities. … Only the dumbest animals would not think about [these possibilities]. … Thought experimentation is just a slightly more elaborate, careful, and reflective version of that process, in the service of some theoretical investigation. Without it, human thought would be severely impoverished.”

Williamson is right. Over thousands of years, some of the best thinkers in history have churned out mountains of these trials and errors of the imagination, and they have the power to fundamentally change the way we navigate the world. They’ve certainly changed the way I do.

You see, I’m a writer, and I try to write fiction and philosophy. Like all writers, though, I’ve heard the advice that you have to “write what you know.” But Socrates said, “The only thing I know is that I know nothing.” And then there was Ernest Hemingway, who once described his own process by saying, “All you have to do is write one true sentence.” But it has become common now to hear that we live in a “post-truth” world. So how do we reconcile these bits of philosophy with the conventional advice to a writer? The answer I found came from philosophical thought experiments, which shows just how powerful and useful they can be.

A few years ago, I came across Julian Baggini’s book The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten and 99 other Thought Experiments. Since I’m always looking to test out my ideas, I decided to go through them all, one-by-one, for the next two years or so on my website. Many of the thought experiments taught me many different and valuable lessons, but there were three in particular that helped me arrive at an answer to the simple question of how to write “true” sentences.

First, there’s Zeno’s paradox. In the version of this that I like, a race is set up between Achilles and a tortoise. The tortoise is given a generous head start, but since Achilles is much faster, he should have plenty of time to catch him. The problem, however, is that Zeno says there is no way he can ever catch the tortoise. At least not according to logic. Zeno explains this by showing how Achilles will first have to run to the place that the tortoise started from. But by that time, the tortoise will have moved further down the track. So now, Achilles will have to run to that spot. But once again, the tortoise will have moved on. And since this will happen over, and over, and over, there’s just no way that Achilles can ever catch the tortoise. Of course, in real life, we know that faster runners overtake slower ones all the time. So how do we solve this paradox?

The short answer to me is that as Achilles approaches the tortoise, Zeno is asking us to divide time into smaller and smaller increments, slowing time down, until we basically have to stop, and wait, while the philosopher continues to calculate smaller and smaller distances, possibly even beyond the smallest increments in the fabric of space-time. But of course, that’s impossible. As the saying goes, time waits for no man. The universe always keeps moving. And so, Achilles can, and does, pass his tortoise.

The second memorable thought experiment for this topic of truth is the one about Descartes’ evil demon. This isn’t so much a story, as it is just the creation of a really gripping character. You see, Descartes, like a lot of philosophers, really wanted to be right. He desperately wanted to prove that there was some foundation upon which all knowledge could be built. But in order to do that, he knew that he had to defeat the most powerful and pesky demon imaginable, one that just might be out there waiting to trick us and our senses.

In Baggini’s treatment of this experiment, he notes that many of us may have seen shows where a hypnotist gets an audience member to swear that 2 + 2 = 5. Now if this idea is even plausible, how do we know that we aren’t all being tricked? What would happen if we all just snapped out of it some day and saw things totally differently? Now this sounds crazy. And we certainly don’t live in the world as if it were like this. But the point is that this kind of hyperbolic doubt exists, because, as we saw in Zeno’s paradox, the universe is always moving and changing. We cannot stop it, and more importantly, we cannot see into the future. And this, therefore, makes us doubt all knowledge. At least just a little bit. That’s an ancient position in philosophy called scepticism, which Professor Williamson mentions in his book, but he dismisses it rather quickly. He simply says, “Sceptics will be only too pleased to exploit [their] power to drag you into the sceptical pit with them. You had best be careful whom you talk to.”

But that brings us to the third thought experiment, the Gettier problem, which I think helps us see how we can talk to these sceptics, and deal with them just fine. The Gettier problem looks at the concept of knowledge, which, ever since Plato, has been defined in the West as justified, true, belief. But Edmund Gettier managed to overturn that dominant definition with just a short two-page paper published in 1963. Honestly, Gettier’s examples are really boring — they aren’t good art — which is possibly why this hasn’t reached a wider audience. But the version that Baggini used to illustrate it is much better, so I’ll use that one to introduce it.

Baggini tells us about a woman called Naomi who was at a coffee shop when she noticed a really unusual man behind her drop a really unusual keychain. She didn’t talk to him, but he was just one of those people that makes a deep impression. The very next day, Naomi was walking down the street when she witnessed a tragic accident — a car killed a pedestrian, and it turned out to be the very same man! The police interviewed Naomi to get some help identifying the body, and she told them about the coffee shop and the odd keychain, both of which turned out to be true. A week later, however, Naomi was back in the coffee shop again when she turned around and screamed. She saw the very same man fumbling with the very same keychain. He quickly calmed her down though and said that this had been happening a lot lately, ever since his twin brother had been killed last week.

This might sound innocent enough, but Naomi is an example of someone who had good justifications, for her beliefs, and those beliefs turned out to be true. But this was only because she was lucky. She might just as easily have seen the twin brother during one of her first two encounters, and then her knowledge would have been wrong. The problem for philosophers is that we never seem to have enough facts to justify our knowledge as being true. The so-called JTB Theory of Knowledge collapses, not because our justifications aren’t robust and durable, but because Zeno’s Paradox and Descartes’ Evil Demon showed us that these justifications cannot get us to the truth. At least, not in any way that we can know it. (Note: this is an epistemological claim about what we can know, not an ontological claim about whether truth can exist.)

This might sound like a really scary admission. But all good scientists demonstrate this when they tell us that their discoveries are only ever provisional, that they could be overturned with any new observations. These scientists are using an evolutionary epistemology. To them, knowledge can only ever be justified, beliefs, that are currently surviving our best tests. This is what I call my JBS Theory of Knowledge. No number of scientific observations will prove that theory, but with the help of a few carefully constructed and creatively designed thought experiments, I think we can confidently arrive at its conclusion.

So, there may not be “truth,” and as an author I may not be able to write “true sentences.” But we can all tinker around and experiment with trial and error to try to think and write things that survive. And sometimes they will. Possibly even for a long time. That’s the best we can do with all of our thought experiments — the artistic ones, and the ones of reason. I think this is great news because it means authors and philosophers will never run out of work. This is also why Williamson’s book isn’t called How Philosophy is Done. Philosophy is not, and seemingly never could be, a finished product — it’s an ongoing verb. And that’s why I highly recommend picking up one of the many collections of thought experiments that are out there. They’re a great way to sit back and enjoy a bit of fiction, and as Williamson advocates, an even better way to keep doing philosophy.

------------

Ed Gibney is a writer and evolutionary philosopher who blogs about his beliefs and the fiction it inspires at evphil.com