------------------------------------------------------------------

Bridging the Is-Ought Divide

Life is. Life ought to act to remain so.

“The naturalistic fallacy…seems to have become something of a superstition. It is dimly understood and widely feared, and its ritual incantation is an obligatory part of the apprenticeship of moral philosophers and biologists alike.” [1]

Competing Oughts

You ought to keep the Sabbath holy. You ought to honor your ancestors. You ought to kill your daughter if she’s dishonored your family. You ought to treat others as you would wish to be treated yourself. You ought to hold the door open for strangers. You ought to listen to your gut. You ought to cut down on your intake of saturated fats. You ought to act “only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.” [2] Oughts come from many different sources—various world religions, socially agreed upon norms, biological urges, scientific recommendations, philosophical arguments—and so far these systems have remained separate, agreeing in some areas, contradicting in others. These oughts are what make up our morals. [3]

Morality, from the Latin moralitas, meaning manner, character, or proper behavior, is “the differentiation of intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good and those that are bad.” [4] It’s “a conformity to the rules of right conduct.” [5] But who gets to define what good, bad, or right mean? Philosophers have fallen into divided camps over this issue, setting up tents as deontologists, consequentialists, virtuists, and nihilists. Social scientists and positive psychologists have meta-studied commonly accepted ethical systems to try to unite them into standard lists of morals and virtues. [6] None of these ethical systems, however, have ever been grounded in objective facts that offer conclusive justification for their existence, so humanity has thus far been left to either rely on revealed dogmas or ignore the relativism that lurks beneath persistent questioning about our morals. Why is this still the case?

The Is-Ought Divide

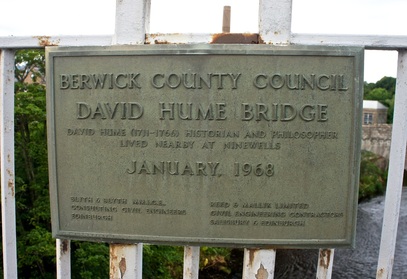

Since at least the beginning of ancient history, religions have claimed to know what is good and bad according to some kind of divine revelation. Around 400BCE though, Plato recorded Socrates asking a religious expert named Euthyphro, “Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?” The Euthyphro Dilemma [7], as it is known, perfectly frames the question of whether or not there is an independent source for morality, beyond what gods or men say that it is. This question has been tackled by legions of philosophers ever since, but in 1739 David Hume made what has become the definitive argument against most of these attempts. Hume compared moral values to “sounds, colors, heat, and cold,” which “are not qualities in objects, but perceptions in the mind.” [8] Having established this subjective nature of moral values as something different than objective facts about the world, Hume then chastised those who ignore this difference:

“In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary ways of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when all of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation, 'tis necessary that it should be observed and explained; and at the same time that a reason should be given; for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it.” [8]

Although Hume’s use of the double negative (“no proposition not connected”) may be confusing out of context, he is universally understood to have meant that “it seems inconceivable that a moral conclusion can be a deduction from premises that are entirely different from it.” [9] In short, there can be no ought from is; at least not directly by using logic alone.

Many philosophers assume that Hume therefore closed the door on deriving morals (what we ought to do) from the natural world (what is), but this is simply wrong. Hume himself was “a naturalist, since he supposed that there are moral truths, which are made true by natural facts, namely facts about what human beings are inclined to approve of.” [9] This sentiment is succinctly captured in another of Hume’s famous quotes: that “reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions.” [10] When he said this, Hume “provided the classical statement of the view that moral values are the product of certain natural human desires. Hume argued that human behavior is a product of passion and reason. Passions set the ends or goals of action; and reason works out the best available means of achieving these ends.” [11]

So when Hume said there can be no ought derived from an is, he didn’t mean it can never be done; he simply meant it cannot be done without a want. This is how we navigate the world all the time using our passions. You want some chocolate. There is chocolate in the cupboard. You ought to go to the cupboard. You want to visit your sister in Poughkeepsie. There is a train at 8am to get there from here. You ought to take the 8am train. Hume was right to say that it makes no sense to claim the third parts of these arguments (the ought statements) follow from their second parts (the is statements) without initially setting down their first premises (the want statements), and he was right to say that the same reasoning applies to our moral passions. You can’t say that Max is a cheater and you ought to punish Max without clearly stating the desire or want that drives this conclusion. But what are these wants and where do they come from? Could they come from nature?

The Naturalistic Fallacy

Any time someone tries to provide justification for morality from the world as it is, the next refrain philosophers will usually utter is that any such attempt to do so is “committing a naturalistic fallacy.” This phrase is derived from G.E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, which was published in 1903. But what did Moore really mean when he coined this term? Hilary Putnam believed that Moore had demonstrated that: “Good was a ‘non-natural’ property, i.e., one totally outside the physicalist ontology of natural science,” [12] and this interpretation has led many to assume that it is a fallacy to claim that moral goodness is part of the natural world. But Putnam’s interpretation was wrong and so all the follow-on assumptions don’t truly… follow on. Let’s unpack the two terms in Moore’s phrase to see where Putnam went awry.

Moore “called the mistake of identifying an object of thought with its object a fallacy. And if the object—with which one mistakenly identified the thought—happened to be a natural object, as opposed to metaphysical entity, then the error became the naturalistic fallacy.” [13] But Moore used the term “natural to refer to properties of the external world. He contrasted natural with intuitive, which he used to refer to properties of the mind—including objects of thought such as good. Hence when Moore claims that good is not a natural property, he is simply restating the point that good is an intuitive object of thought and not an objective feature of the outside world.” [14] What Moore was actually saying was the same thing as Hume. While Hume used perceptions in the mind to point out where good resides, Moore rephrased slightly and used object of thought as its location. And so just as Hume did nothing to rule out nature from driving our morality (in the form of human thought driven by our natural wants), neither did Moore—at least not to anyone who discarded Descartes’ dualism long ago.

In fact, a survey of the literature reveals that there are eight so called naturalistic fallacies [15] that include various interpretations of Hume and Moore, and none of them actually preclude an objective source of morality coming from natural human desires. As Curry concludes in his paper Who’s Afraid of the Naturalistic Fallacy?:

“Whenever someone uses the term “naturalistic fallacy,” ask them “Which one?,” and insist that they explain the arguments behind their accusation. It is only by bringing the ‘fallacy’ out into the open that we can break the mysterious spell that it continues to cast over ethics.” [16]

As John Mackie stated:

“It is not for nothing that [Hume’s] work is entitled A Treatise of Human Nature, and subtitled, An attempt to introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral subjects; it is an attempt to study and explain moral phenomena (as well as human knowledge and emotions) in the same sort of way in which Newton and his followers studied and explained the physical world.” [17]

As Dan Dennett said:

“If ‘ought’ cannot be derived from ‘is,’ just what can it be derived from? … ethics must be somehow based on an appreciation of human nature—on a sense of what a human being is or might be, and on what a human being might want to have or want to be. If that is naturalism, then naturalism is no fallacy.” [18]

The various interpretations of the naturalistic fallacy are, in fact, quite easily flipped on their heads and retorted back as “supernaturalistic fallacies.” In a universe with no evidence of supernatural intervention, where else do morals (or anything for that matter) come from but from nature? As Charles Pigden wrote:

“[T]here is no need for naturalists to evade the arguments of Moore and Hume … Insofar as they are valid, Hume’s arguments, and Moore’s too, are compatible with naturalism. Formal attempts to refute naturalism having failed, it remains a live option.” [19]

As I hope to now show, naturalism remains very much a “live” option indeed!

The Want That Must

So the is-ought divide is not an uncrossable chasm—it just requires a bridge to make the connection. We have established that oughts can come from is as long as they are driven by a want. So if we are to find an objective and universal basis for morality, then we must therefore find an objective and universal want. Additionally, as Christine Korskgaard writes, “When we seek a philosophical foundation for morality we are not looking merely for an explanation of moral practices. We are asking what justifies the claims that morality makes on us.” [20] So not only must this fundamental want that we seek be objective and universal, it must somehow justify its claim on us as well. What are some of the wants we might consider?

We can look to psychology and list out our hierarchy of needs from Maslow. [21] We can want to eat, to sleep, to have sex, to be safe, to be loved, to be respected, to be creative, to solve problems, and to pass on what we have learned. We can look to philosophy and consider the qualities that others have reasoned we ought to want. We can want to be happy, to flourish, to have justice, to be virtuous, to maximize wellbeing, to enjoy freedom, or to become supermen. We can look to theology and listen to what preachers say they have heard from the heavens. We can want to know God, to be saved in the afterlife, to serve Jesus, to obey Mohammed, to become enlightened, or to reincarnate as a higher being. We can study science to see what empirical researchers have uncovered. We can want to pass on our genes, to protect our kin, to cooperate with the group, to maintain purity, or to punish cheaters. Or we can discard all of these findings and determine our own individual wants, even if that means we want something bad or want nothing at all.

In short, we are blindly groping for the right wants as they compete to pull us in many different directions, often simultaneously. And not just groping for any one of these wants, but for some combination of them all, some perfect mix or balance that optimizes whatever it is we can possibly hope to achieve. Some choices work, and we rationally decide to keep them. Others do not, and they are discarded. Does this general process sound familiar? This kind of blind variation and selective retention (BVSR) is “the most fundamental principle underlying Darwinian evolution.” [22] Whether we realize it or not, our moral wants are being selected through evolutionary processes. Which ones will survive? The wants that lead to long-term survival. No other criteria can outweigh this fundamental outcome that is both objective and universal and justifies its claims on us with its logical inevitability. If we, as a species, were to choose wants that did not lead to our survival, then we, and those wants, would go extinct. Therefore, we ought to want to survive over the long term. We can choose otherwise. Nothing in this universe says we must choose this path. But no other want will come out of an evolutionary process, and the history of science tells us we are locked in just such a universe—one that is governed by evolutionary processes where things on a macro scale don’t just wink in and out of existence by natural or supernatural means. We ought to accept that fact and align our moral obligations with it. Nothing else can subvert this fact or override it. This is the fundamental, objective, universal, and justified basis on which human morality is built. All other wants are proximately caused in service of this ultimate cause. [23]

To see this from another direction, let’s go back to Hume. As he put it in one of his later works:

“Ask a man why he uses exercise; he will answer, because he desires to keep his health. If you then enquire, why he desires health, he will readily reply, because sickness is painful. If you push your enquiries farther, and desire reason why he hates pain, it is impossible he can ever give any. This is an ultimate end, and is never referred to any other object. … And beyond this it is an absurdity to ask for a reason. It is impossible there can be a progress in infinitum; and that one thing can always be a reason why another is desired. Something must be desirable on its own account, and because of its immediate accord or agreement with human sentiment and affection.” [24]

Sadly, Hume wrote this in 1777, just over 80 years before Darwin was to publish On the Origin of Species. Had he been introduced to that book and been able to think through the ramifications of evolution, Hume may have arrived through his root cause analysis at the fact that existence is the ultimate end, and survival is the thing that must be desired on its own account. Prior to existence—or after it is extinguished—there are no human desires. If the state of existence is not satisfied, then there is no one to answer any further inquiries. There would be no more passions to drive our reason. Even if our ontological questions about the universe have no regressive end to them at the moment, our moral questions about our place in this universe do have an end. They end with whether or not we will continue to exist. The fundamental nature of being implied by the use of the word is, is the very thing that helps us get from is to ought. We are alive. We want to remain alive. We ought to act to remain so.

Expanding the Circle

So far, we have been talking about human morals and human concerns, but is that enough? And when I say, “we are alive,” who exactly am I talking about? An individual? A family? A tribe? A race? A nation? The human species? Is that consideration even enough? If we say that the ultimate want is long-term survival, then whose survival needs to be considered as part of that desire?

In The Expanding Circle, philosopher Peter Singer argued that “altruism began as a genetically based drive to protect one’s kin and community members but has developed into a consciously chosen ethic with an expanding circle of moral concern.” [25] Singer described the growth of this expanding circle by starting with the selfish concerns of one individual and using moral reasoning to show how it widens step by step to eventually encompass all of humanity:

“If I have seen that from an ethical point of view I am just one person among the many in my society, and my interests are no more important, from the point of view of the whole, than the similar interests of others within my society, I am ready to see that, from a still larger point of view, my society is just one among other societies, and the interests of members of my society are no more important, from that larger perspective, than the similar interests of members of other societies ... Taking the impartial element in ethical reasoning to its logical conclusion means, first, accepting that we ought to have equal concern for all human beings.” [26]

Singer went on to extend this ethical scope to include all sensitive species, but that has remained a contentious idea even as societies have enacted more prohibitions against cruelty to animals. Setting that controversy aside for the moment, however, Singer does bring us to a larger point. While we have been discussing morals and how they are rules for living, we have been led to talk about individuals, species, and survival over long terms. We began to talk about issues concerning biology, and in particular the natural sciences of biology, sociobiology, ecology, and evolutionary biology. This makes sense as biology is the study of life and we are talking about rules for living, but I would like to make the connection even clearer and stronger by outlining the entirety of the circle that Singer began to push into shape.

In 1998, biologist E.O. Wilson published the book Consilience in which he complained about the general splintering of knowledge that kept scientists in the dark about facts that had already been discovered in other fields. In particular, he bemoaned the divide in his own area of specialty and noted the means by which they could be united. He wrote that the “conception of scale is the means by which the biological sciences have become consilient during the past fifty years. According to the magnitude of time and space adopted for analysis, the basic divisions of biology” from the bottom to the top are: [27]

(1) Biochemistry -> (2) Molecular Biology -> (3) Cellular Biology -> (4) Organismic Biology -> (5) Sociobiology -> (6) Ecology -> (7) Evolutionary Biology

These seven mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive categories [28] describe the study of life in its totality. They provide the list of individual lenses we need to look through to understand everything there is to know about life. These lenses can also, therefore, be used to study and understand morals through ever-widening circles, and I believe this is particularly instructive. For example, to follow Singer’s descriptions, personal interests such as individual flourishing make sense in the light of needs at the organismic biology level, societal interests such as justice and cooperation make sense in the light of needs at the sociobiological level, and the welfare concerns for other sensitive creatures makes sense in the light of needs at the ecological level. By bringing in this comprehensive analytical model from the field of biology, we see that Singer’s circle makes sense, it just fails to expand wide enough to take into account the needs of societies and ecologies over evolutionary timeframes. It also fails to narrow down small enough analyze our moral history by examining the lower three levels of biology using morally-loaded analogies.

Imagine various oughts evolving over time, always remembering that the ultimate want is survival. We could then imagine telling the following morality plays about the history of the evolution of life on Earth (while keeping in mind that I’m using poetic license to ascribe intentions to entities that clearly have none). For example, “1. The Morals of Biochemistry”: These chemicals bond readily to those chemicals to form a useful compound. But those chemicals are in short supply and being wasted in other bonds. These chemicals ought to bond with all of those chemicals. The end. (This first play has no tradeoffs in it so it’s rather boring.) Then we progress to “2. The Morals of Molecular Biology”: But what if no chemicals are left over for other useful compounds? Our first compounds would benefit from combining with other useful compounds. Those first compounds ought to leave some chemicals for other compounds so that together they can make a really useful compound called a molecule. The end. You can repeat the storyline for yourself through the levels of cellular biology (3) building the first complex organisms (4), which evolve into cooperative societies (5) and fill niches in the ecology (6), which all change over evolutionary timeframes (7). Each story, over and over, being one of competition in the short term giving way to broader cooperation over the long term for the benefit of all.

Of course, the lack of “free will” (here, I mean freedom to choose) within the first three levels of biochemistry, molecular, and cellular biology mean that we must project our emotional pulls onto the actors in those plays. But given their roles as our own ancestors and building blocks, we find it easy to do so and root heartily for them to succeed. After that, the procession is easy to follow. Can a man act to survive at the expense of others? Not for very long, and not if he has a choice, for he would eventually be faced with fighting nature alone. He must cooperate with others to survive. Can groups act to survive at the expense of other groups? Not for very long. We need vast connections of cooperation to ensure the progress of civilizations that provide us with robust diversity and adaptability. We must cooperate as a species to survive. Can a species act to survive at the expense of other species? Not for very long. We are enmeshed in a complex web of life that makes up a supportive ecosystem. Species must cooperate with other species to fill the niches necessary for an environment to thrive. Can environments remain intact in a static manner? Not for very long. The universe changes and individuals within species within ecosystems must cooperate with one another to adapt to these changing conditions over evolutionary timeframes.

These are the tradeoffs that must be addressed correctly by our moral urges if we are to survive. These are the base sources of all our competing wants, which drive all our competing oughts, which our systems of ethics must choose between. By utilizing the comprehensive framework for biology to understand the totality of wants for all forms of life, we come to a clearer understanding of morality, which seeks to satisfy those wants in an optimal manner. In general, the focus of morality in the past has centered on the middle circles of this biological spectrum—the organismic and societal levels—since those are the most obvious areas for our concern. The smallest end of the biological scale does not really enter into our considerations because there is no free will there. The largest end has only recently entered into our considerations because the theory of evolution has only recently been grasped and there is much epistemic opacity there (it is very hard to know what we see and predict the future given such massive complexity in the system), which casts doubt over inquiries into and hypotheses about that realm. Still, we can see that this all-encompassing biological landscape for morality is the one that makes logical sense.

If my hypothesis about morality is true, that it is a growing concern for the survival of life over larger and larger circles of concern, then this should lead to some predictions. Perhaps our moral emotions would have evolved along this path. This has not been fully investigated, but we do in fact see some evidence for this progression of morality going from concern for the self to concern for others in the evolutionary past of our brain structures. Evolutionary neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp of Bowling Green State University has identified seven emotional systems in humans that originated deeper in our evolutionary past than the Pleistocene era. The emotional systems that Panskepp terms Care (tenderness for others), Panic (from loneliness), and Play (social joy) date back to early primate evolutionary history, whereas the systems of Fear, Rage, Seeking, and Lust, which govern survival instincts for the individual, have even earlier, premammalian origins. [29] This is a tantalizing fact that begs to be investigated as part of an empirically driven science of morality, were an objective basis for the field to be accepted as has been proposed in this essay.

Bridging the Is-Ought Divide

To reiterate, there is no supernatural force that dictates anything must follow rules for survival, but this blind and unsympathetic arbiter of the selection process within our universe means that this is the ultimate judge of all actions. We see this on all the circles of our biology and we see that it holds true for other species as well. Those pandas ought to want to mate more to ensure the survival of their species. Those humans ought not to want to act in a manner that wipes out bees because their own food chain depends on it. Those trees ought to grow at higher elevations because the habitat they are in is changing. Etc. etc. These actions are all different depending upon the species, the environment it is trying to survive in, and the ability of individuals to make moral decisions, but all of these oughts must obey the same logic of leading towards survival. All of these oughts therefore lead us to a final inference about a moral rule that objectively, universally, justifiably, and ultimately compels our actions. The prescription of morality can thus be generalized to apply to all of life, for the remainder of time. This is our conclusion:

1. Life is.

2. Life wants to remain an is. [30]

3. Therefore, life ought to act to remain alive.

The first two premises are irrefutably true from observation. The conclusion is logically valid and becomes the final test by which all moral standards must be judged.

Across the Bridge to the Other Side

Okay, so we have an objective basis for morality. Now what? Is the way forward clear? Are the answers to all of our moral dilemmas suddenly obvious? Hardly. But that’s okay, because any framework for morality that does not account for the friction that has continually accompanied our difficult moral choices is a framework that does not account for reality. We would not have such a long history of questions in this sphere if we did not have an extremely complicated set of competing wants that we all feel and must try to make sense of. But at least now we can see the locations of all those sticking points. All moral dilemmas can be understood as conflicts somewhere along the consilient spectrum of biology. [31]

Our intuitive moral feelings are often in conflict because of the debates that rage within us regarding the self vs. society, or society vs. the environment, or the short-term vs. the long-term, or just the fundamental choices between competition and cooperation. This is what drives the two faces of mankind. We are neither inherently good nor inherently evil—we are capable of both, a flexibility we must have in order to have the power to choose between alternate paths that are right some of the time and wrong some of the time.

As we learn what the right path is over the long term though, we develop cultural norms to enforce good behavior along those lines, even though other ways are still possible. Sometimes, after further review, changes to those norms occur when individuals are able to convince groups that their current path is leading away from that which enables the long-term survival of life. Even if other proximate reasons are given, there will always be this final backstop that ultimately proves whether the changes in our moral norms are correct or not. As we finally come to recognize this, will it mean we have to change all our previously held moral beliefs? Of course not, although we would if we discovered we were on the path towards extinction.

Fortunately, life has already been selected for figuring out ways to balance the concerns that individuals and groups must take into account. It’s only recently that we’ve discovered this (recent in comparison to the field of philosophy anyway), but research in fields such as game theory, evolutionary biology, animal behavior, and neuroscience has shown us that humans and other animals have natural dispositions to act for the common good of their kin, social group, species, and ecosystems, and even over evolutionary timeframes. Under certain circumstances, organisms will be social, cooperative, and even altruistic. Using terms such as kin altruism, coordination, reciprocity, and conflict resolution, evolutionary theory has explained why and how some organisms care for their offspring and their wider families, aggregate in herds, work in teams, practice a division of labor, communicate, share food, trade favors, build alliances, punish cheats, exact revenge, settle disputes peacefully, provide altruistic displays of status, and respect property. [32] All of these behaviors clearly lead to prolonged survival for the groups of individuals that exhibit them.

We can learn from these and other examples of what has worked in the past to generalize about how we as a species must move forward into the future. What traits do we currently believe will lead to survival over the long term? Suitability to an environment. Adaptability to changes in the environment. Diversity to handle fluctuations. Cooperation to optimize resources and reduce the harm that comes from conflict. Competition to spur effort and progress. Limits to competition to give losers a chance to cooperate on the next iteration. Progress in learning, to understand and predict actions in the universe. Progress in technology, to give options for directing outcomes where we want them to go. These are the virtues and outcomes we must cultivate to face our existential threats and remain determined to conquer them. Traditional moral rules supporting concepts such as charity, honesty, freedom, justice, etc., may also lead us toward these survival traits, but make no mistake that this is the end goal of morality toward which we are headed. We know this now.

We also know the locations of the decision points along the way toward that goal. What are the best means to achieve individual flourishing? How much individual flourishing can we have and still remain cooperative with one another? How can our differing societies experiment with their own ways forward without devolving into utterly destructive competition? How can we balance the progress of humanity with the scarcity of resources needed to fuel that progress? These and many other questions of morality still remain to be answered. Knowing these locations and desired outcomes though will help us empirically evaluate our choices wherever it is possible to experiment with them. Good answers will strike the best balance between all the options. Evil answers will get the mix wrong. Most commonly, evil will involve weighting the needs of an individual too heavily in comparison to the needs of other individuals or other groups. But there will also be instances of evil being done to individuals in the name of social or ecological forces that have been overweighted.

On that note about evil, I’ll close with a word of caution about this new direction we can now take. The probabilistic nature of knowledge means we won’t always know how to solve our moral conflicts—in fact, we may never be certain of some of the answers either before or after we make a decision. How do we proceed then where we don’t know? Carefully of course, and taking a cue from The Black Swan [33], which made a study of this fuzzy realm where consequences of improbable events may be large and especially terrible. Limited trial and error is the way life has blindly found its way through these dark minefields of existence in the past, and anyone that takes a big bet on a non-diversified strategy will eventually lose everything over the billions of repetitions that our existence in evolutionary timescales allows. So even if we become confident about the direction we would like to go, humans should not be lured into racing there using existentially risky behavior. No, change that last part. Humans ought not to do that, now that we know what it is that we ought to be acting towards.

—--

Notes

[1] Curry, O. (2006) Who’s Afraid of the Naturalistic Fallacy? Evolutionary Psychology, Volume 4, p. 243.

[2] The Categorical Imperative from Immanuel Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals 3rd ed. Hackett, p. 30.

[3] For a more nuanced description of the use of the term morality, see the entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy titled The Definition of Morality.

[4] Wikipedia definition of morality.

[5] Dictionary.com definition of morality.

[6] Based on extensive empirical research from around the world, Jonathan Haidt proposed in The Righteous Mind the following foundations for all cultural moralities: 1) Care/Harm; 2) Fairness/Cheating; 3) Liberty/Oppression; 4) Loyalty/Betrayal; 5) Authority/Subversion; 6) Sanctity/Degradation. Martin Seligman, in Authentic Happiness, based on empirical research from around the world and throughout history, proposed the following 24 elements in 6 categories of virtue: I. Wisdom: 1) Curiosity, 2) Love of learning, 3) Judgment, 4) Creativity, 5) Emotional Intelligence, 6) Perspective; II. Courage: 7) Valor, 8) Perseverance, 9) Integrity; III. Humanity: 10) Kindness, 11) Loving; IV. Justice: 12) Citizenship, 13) Fairness, 14) Leadership; V. Temperance: 15) Self-control, 16) Prudence, 17) Humility; VI. Transcendence: 18) Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence, 19) Gratitude, 20) Hope, 21) Spirituality, 22) Forgiveness, 23) Humor, 24) Zest.

[7] The Euthyphro dilemma.

[8] Hume, D. (1739) A Treatise of Human Nature, book 3, part 1, section 1.

[9] Pidgin, C. (2011) Hume on Is and Ought, Philosophy Now Magazine, Issue 83.

[10] Hume, D. (1739) A Treatise of Human Nature, Part 3, Of the will and direct passions, Sect. 3, Of the influencing motives of the will.

[11] Curry, O. (2006) p. 234.

[12] Putnam, H. (1981) Reason, Truth and History, Cambridge University Press, p. 206.

[13] Curry, O. (2006) pp. 238-239.

[14] Curry, O. (2006) p. 239.

[15] From Curry, O. (2006) p. 236: “A survey of the literature reveals not one but (at least) eight alleged mistakes that carry the label “the naturalistic fallacy”: 1) Moving from is to ought (Hume’s fallacy). 2) Moving from facts to values. 3) Identifying good with its object (Moore’s fallacy). 4) Claiming that good is a natural property. 5) Going “in the direction of evolution.” 6) Assuming that what is natural is good. 7) Assuming that what currently exists ought to exist. 8) Substituting explanation for justification.”

[16] Curry, O. (2006) p. 243.

[17] Mackie, J. L. (1980) Hume's Moral Theory, Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd, p. 6.

[18] Harris, S. The Moral Landscape, p. 250, quotes this as from “Dennett p. 468,” but Harris’ reference is sloppy here and does not say which Dennett book he is referring to, though I have little doubt that Dennett said it.

[19] Pigden, C. R. (1991) Naturalism, in Singer, P. (Ed.), A Companion to Ethics, pp. 427-428.

[20] Korsgaard, C. M. (1996) The Sources of Normativity, Cambridge University Press, pp. 9-10.

[21] Maslow, A.H. (1943) A theory of human motivation, in Psychological Review, 50(4), pp 370–396. See the Wikipedia entry.

[22] Entry for Blind Variation and Selective Retention on Principia Cybernetica. The term comes from Joseph Campbell who also coined the phrase “evolutionary epistemology” and noted how BVSR governed the evolution of knowledge in general.

[23] From Wikipedia: “A proximate cause is an event, which is closest to, or immediately responsible for causing, some observed result. This exists in contrast to a higher-level ultimate cause (or distal cause), which is usually thought of as the “real” reason something occurred. Separating proximate from ultimate causation frequently leads to better understandings of the events and systems concerned.”

[24] Hume, D. (1777) An Enquiry Concerning the Principle of Morals, pp. 244-245.

[25] Singer, Peter (1981) The expanding circle: ethics and sociology (1st ed.), book cover description.

[26] Singer, Peter (1981) p. 119.

[27] Wilson, E.O. (1998) Consilience, Vintage Books paperback edition, p 91. Wilson left off the field of sociobiology from his list (I’m guessing because he himself controversially named it and it is not a widely recognized field), but I’ve inserted it in my account to ensure that the continuum from individual to society to species is complete.

[28] The MECE Principle.

[29] Panksepp, J. (1998) Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions, Oxford University Press.

[30] When I talk about “life” here, I recognize that it is not a singular entity with conscious desires. Looking at the specifics of life though, I believe we can generalize this larger rule. I think we can look at a sunflower and say that it “wants” to face the sun. Does it have agency and free will to do so? Most probably not. But there are those who say we humans don’t have agency and free will either, yet we still use the word "want" for our motives. To me, the word "want" does not imply agency, it just implies a chemical / emotional pull. Objectively speaking, we see that living things act to remain alive. We therefore say they "want" to remain alive, even if they are not aware of that fact themselves, and the "wants" are hard coded in their genes.

[31] As Sam Harris pointed out in The Moral Landscape (2010), non-biological objects don’t enter into our area for moral concern. Can I break this rock? You can, as long as it doesn’t disturb any forms of life. Can I eat this carrot? You might not want to if it were the last carrot on earth, because life is currently impossible to recreate once it’s gone, unlike a rock or gas that can be reproduced using physical or chemical processes. This is another example that points to the link between biology and morals.

[32] As listed in Curry, O. (2006) p. 236, these traits have been detailed in many studies, including the following: Aureli, F., and de Waal, F. B. M. (Eds.) (2000) Natural conflict resolution, University of California Press; Axelrod, R. (1984) The Evolution of Cooperation, Basic Books; Clutton-Brock, T. H., and Parker, G. A. (1995) Punishment in animal societies, Nature, 373, 209-216; Crespi, B. J. (2001) The evolution of social behaviour in microorganisms, Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 16(4), pp. 178-183; de Waal, F. (1996) Good Natured: The origins of right and wrong in humans and other animals, Harvard University Press; Hamilton, W. D. (1964) The genetical evolution of social behaviour, Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7, pp. 1-16, 17-52; Hamilton, W. D. (1971) Geometry for the Selfish Herd, Journal of Theoretical Biology, 31, pp. 295-311; Harcourt, A., and de Waal, F. B. M. (Eds.) (1992) Coalitions and Alliances in Humans and Other Animals, Oxford University Press; Hepper, P. G. (Ed.) (1991) Kin Recognition, Cambridge University Press; Johnstone, R. A. (1998) Game theory and communication, in L. A. Dugatkin and H. K. Reeve (Eds.), Game Theory and Animal Behavior, Oxford University Press pp. 94-117; Kummer, H., and Cords, M. (1991) Cues of ownership in long-tailed macaques, Macaca fascicularis, Animal Behaviour, 42, pp. 529-549; Maynard Smith, J., and Price, G. R. (1973) The logic of animal conflict, Nature, 246, pp. 15-18; Trivers, R. L. (1971) The evolution of reciprocal altruism, Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, pp. 35-57; Zahavi, A., and Zahavi, A. (1997) The Handicap Principle: A missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle. Oxford University Press.

[33] Taleb, N. (2010) The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, 2nd Ed., Random House.