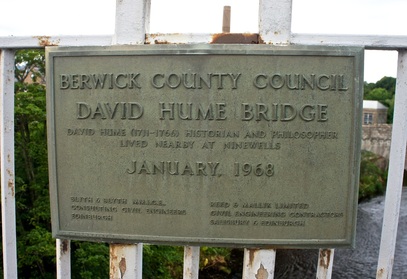

First, as I mentioned at the end of the post, I'd just finished a long paper on how we might now be able to use evolutionary philosophy to finally bridge the is-ought divide that Hume first described. I'm still waiting to hear back from the e-magazine that I've submitted that paper to, but I hope to have news about that soon. Secondly though, I was about to take a short trip to the borderlands of Scotland where, as I learned from writing my blog post, David Hume was born and spent much of his life. Discovering that this location wasn't far from a mountain biking destination I was aiming for made me dig a little deeper, whereupon I found that some passionate folks had actually set up a Border Brains Walk around the lands that Hume's family owned. I hadn't known such a hike was possible, but once I learned about it, it was a given that I'd make the pilgrimage to see his home.

Bridging the Is-Ought Divide.

Life is. Life ought to act to remain so.

“The naturalistic fallacy…seems to have become something of a superstition. It is dimly understood and widely feared, and its ritual incantation is an obligatory part of the apprenticeship of moral philosophers and biologists alike.” [1]

Competing Oughts

You ought to keep the Sabbath holy. You ought to honor your ancestors. You ought to kill your daughter if she’s dishonored your family. You ought to treat others as you would wish to be treated yourself. You ought to hold the door open for strangers. You ought to listen to your gut. You ought to cut down on your intake of saturated fats. You ought to act “only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.” [2] Oughts come from many different sources—various world religions, socially agreed upon norms, biological urges, scientific recommendations, philosophical arguments—and so far these systems have remained separate, agreeing in some areas, contradicting in others. These oughts are what make up our morals. [3] Morality, from the Latin moralitas, meaning manner, character, or proper behavior, is “the differentiation of intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good and those that are bad.” [4] It’s “a conformity to the rules of right conduct.” [5] But who gets to define what good, bad, or right mean? Philosophers have fallen into divided camps over this issue, setting up tents as deontologists, consequentialists, virtuists, and nihilists. Social scientists and positive psychologists have meta-studied commonly accepted ethical systems to try to unite them into standard lists of morals and virtues [6]. None of these ethical systems, however, have ever been grounded in objective facts that offer conclusive justification for their existence, so humanity has thus far been left to either rely on revealed dogmas or ignore the relativism that lurks beneath persistent questioning about our morals. Why is this still the case?

Since at least the beginning of ancient history, religions have claimed to know what is good and bad according to some kind of divine revelation. Around 400BC though, Plato recorded Socrates asking a religious expert named Euthyphro, “Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" The Euthyphro Dilemma [7], as it is known, perfectly frames the question of whether or not there is an independent source for morality, beyond what gods or men say that it is. This question has been tackled by legions of philosophers ever since, but in 1739 David Hume made what has become the definitive argument against most of these attempts. Hume compared moral values to “sounds, colors, heat, and cold,” which “are not qualities in objects, but perceptions in the mind.” [8] Having established this subjective nature of moral values as something different than objective facts about the world, Hume then chastised those who ignore this difference:

“In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary ways of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when all of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation, 'tis necessary that it should be observed and explained; and at the same time that a reason should be given; for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it.” [9]

Although Hume’s use of the double negative (“no proposition not connected”) may be confusing out of context, he is universally understood to have meant that “it seems inconceivable that a moral conclusion can be a deduction from premises that are entirely different from it.” [10] In short, there can be no ought from is; at least not directly by using logic alone.

So when Hume said there can be no ought derived from an is, he didn’t mean it can never be done; he simply meant it cannot be done without a want. This is how we navigate the world all the time using our passions. You want some chocolate. There is chocolate in the cupboard. You ought to go to the cupboard. You want to visit your sister in Poughkeepsie. There is a train at 8 am to get there from here. You ought to take the 8 am train. Hume was right to say that it makes no sense to claim the third parts of these arguments (the ought statements) follow from their second parts (the is statements) without initially setting down their first premises (the want statements), and he was right to say that the same reasoning applies to our moral passions. You can’t say that Max is a cheater and you ought to punish Max without clearly stating the desire or want that drives this conclusion. But what are these wants and where can they come from? Can they come from nature?

TO BE CONTINUED

Endnotes

- Curry, O. (2006) Who’s Afraid of the Naturalistic Fallacy? Evolutionary Psychology, Volume 4, p. 243. http://www.epjournal.net/wp-content/uploads/ep04234247.pdf

- The Categorical Imperative from Immanuel Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals 3rd ed. Hackett, p. 30. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Categorical_imperative

- For a more nuanced description of the use of the term morality, see the entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy titled The Definition of Morality. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/morality-definition/

- Wikipedia definition. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morality

- Dictionary.com definition. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/morality?s=t

- Based on extensive empirical research from around the world, Jonathan Haidt proposed in The Righteous Mind the following foundations for all cultural moralities: 1) Care/Harm; 2) Fairness/Cheating; 3) Liberty/Oppression; 4) Loyalty/Betrayal; 5) Authority/Subversion; 6) Sanctity/Degradation. Martin Seligman, in Authentic Happiness, based on empirical research from around the world and throughout history, proposed the following 24 elements in 6 categories of virtue: I. Wisdom: 1) Curiosity, 2) Love of learning, 3) Judgment, 4) Creativity, 5) Emotional Intelligence, 6) Perspective; II. Courage: 7) Valor, 8) Perseverance, 9) Integrity; III. Humanity: 10) Kindness, 11) Loving; IV. Justice: 12) Citizenship, 13) Fairness, 14) Leadership; V. Temperance: 15) Self-control, 16) Prudence, 17) Humility; VI. Transcendence: 18) Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence, 19) Gratitude, 20) Hope, 21) Spirituality, 22) Forgiveness, 23) Humor, 24) Zest.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euthyphro_dilemma

- Hume, D. (1739) A Treatise of Human Nature, book 3, part 1, section 1.

- Hume, D. (1739).

- Pidgin, C. (2011) Hume on Is and Ought, Philosophy Now Magazine, Issue 83. http://philosophynow.org/issues/83/Hume_on_Is_and_Ought

- Pidgin, C. (2011).

- Hume, D. (1739) A Treatise of Human Nature, Part 3, Of the will and direct passions, Sect. 3, Of the influencing motives of the will.

- Curry, O. (2006) p. 234.