- What is a humanist worldview?

- What is an evolutionary worldview?

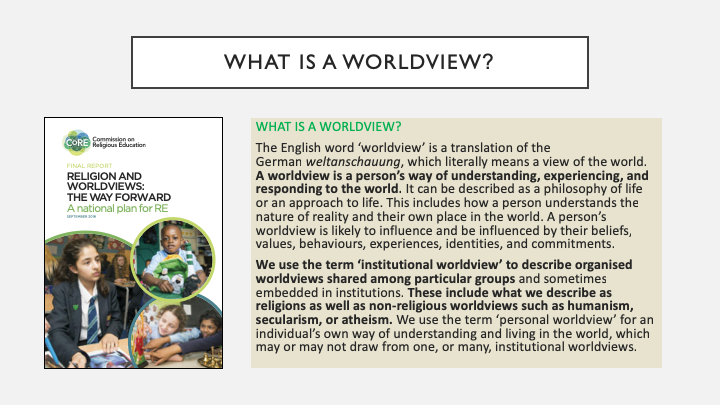

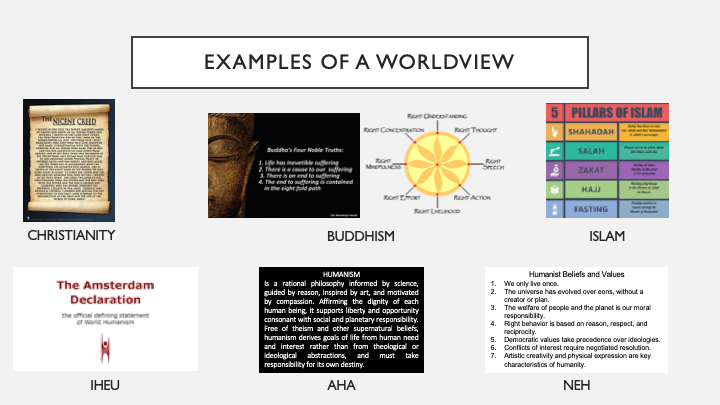

- And more fundamentally, what is a worldview? How can we actually compare these sorts of things?

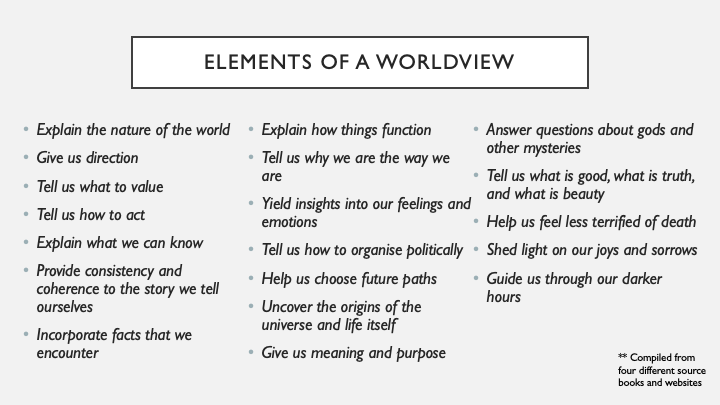

- Tell us how to act

- Tell us how to organize politically

- Give us meaning and purpose

- Tell us what is good, what is truth, and what is beauty

- And many other things as well

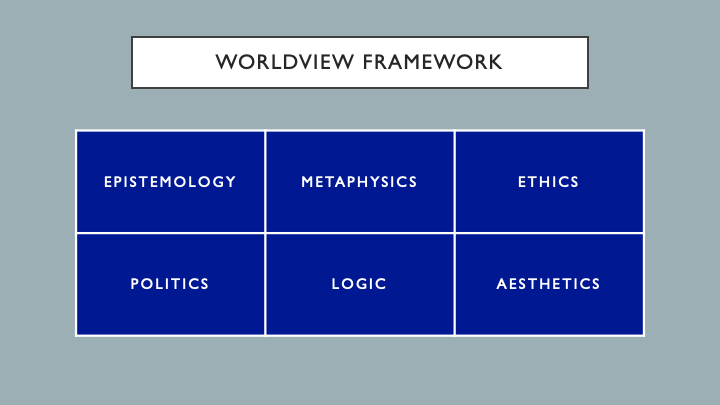

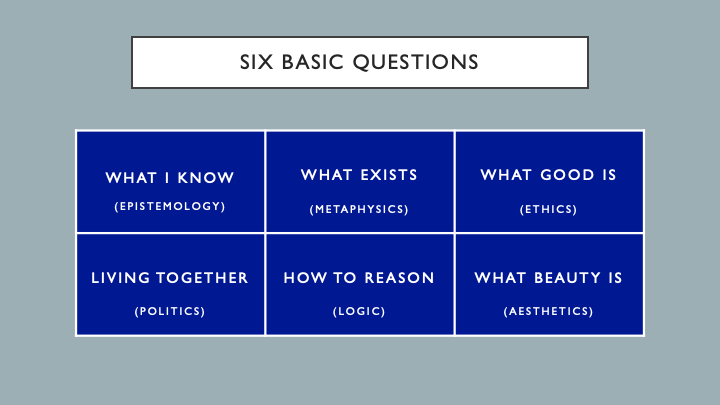

But once the scientific method was defined during the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods, basically any time a subject became understood well enough to be tested empirically, these pursuits were then split off into their own discipline. This is why some people have characterised the history of philosophy as one that spawns science. And so now, philosophers are left with only the most difficult things that we can’t quite wrap our arms around to measure and be certain about. That’s where radical choices can still made about what to believe in or not to believe in. In other words, this is where we can still find the greatest differences in our worldviews.

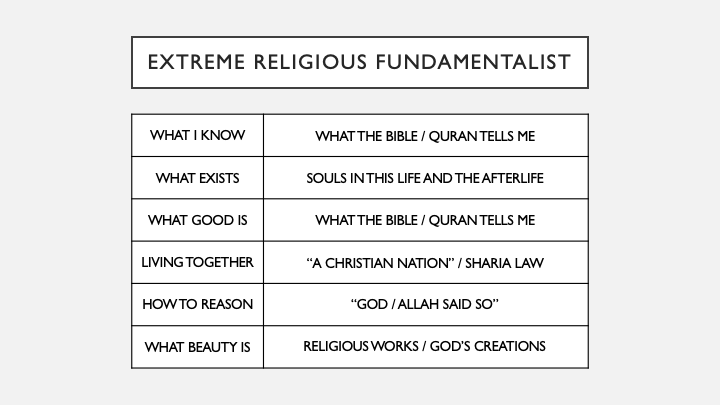

So, again, this is just a simplified example. Most people, even religious fundamentalists, are more complicated and nuanced than this. But I hope it shows that if you go through the details of these six items for a person or an institution, then you should begin to have a very good idea of what they are like.

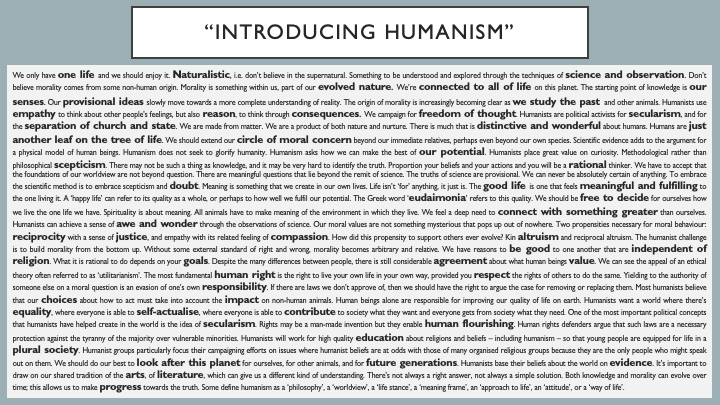

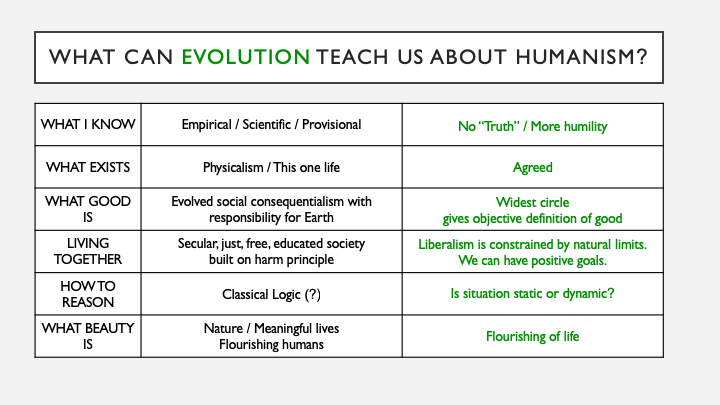

So, taking that into account, a humanist might say that what we know comes from empirical observations only. Since there are no revelations from gods available to us, that leaves us with the scientific method, very broadly defined, as the only way to gain knowledge. And that knowledge is only ever provisional, because new observations might come along at any time that contradict what we currently believe, and we have to remain open to that.

As far as what exists then, we’ve never detected any supernatural interventions in the universe, so we’re left with natural descriptions, or what is known as physicalism in philosophy. Without any reason to believe in a heaven or hell, humanists focus on this one life, and we try to make it a good one.

So, what is good? Well, humanists think we get a sense of that from being social creatures who have evolved reasons to feel empathy and take care of one another, or indeed of any living thing that can feel pain and suffering. The course also mentioned repeatedly that because there aren’t any gods coming to save us, it’s up to us to take responsibility for the Earth and everything that we do to it.

Politically, humanists have had a long tradition of campaigning for secular, just, free, and educated societies, in particular focusing on issues of human rights. In liberal democracies, this is built on something called the harm principle, which I’ll talk a bit more about later, but basically it means that we should be free to do what we want as long as we don’t harm others with our actions.

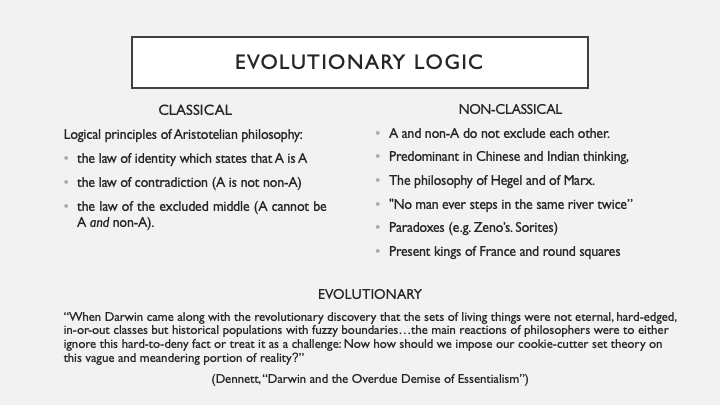

The online course didn’t mention anything specific about the field of logic, but it did point out that we need to use reason and rationality to make our way through the world, so I’ve assumed there was an acceptance of what is called classical logic here.

Finally, the course did end by noting that we humanists, contrary to what some might think, can also experience awe, beauty, and purpose, by simply enjoying nature, leading meaningful lives, or helping other humans flourish.

So, altogether, this is the summary that I’ve put together of what the humanist worldview is, and it’s something I definitely want to hear your opinions on during the Q&A. But before we get to that, I want to go through some of my own philosophy and see how that might support or challenge some of these ideas.

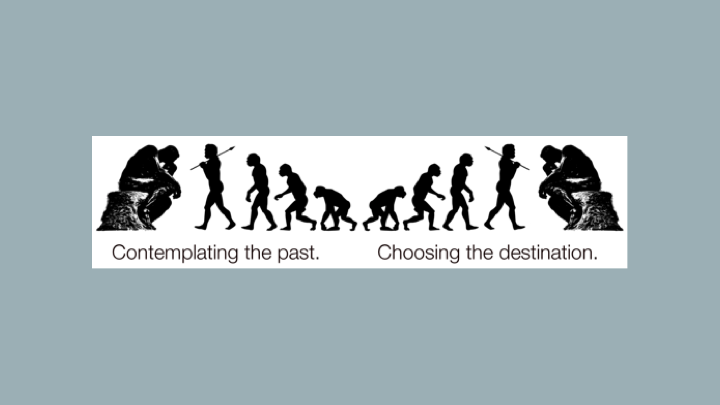

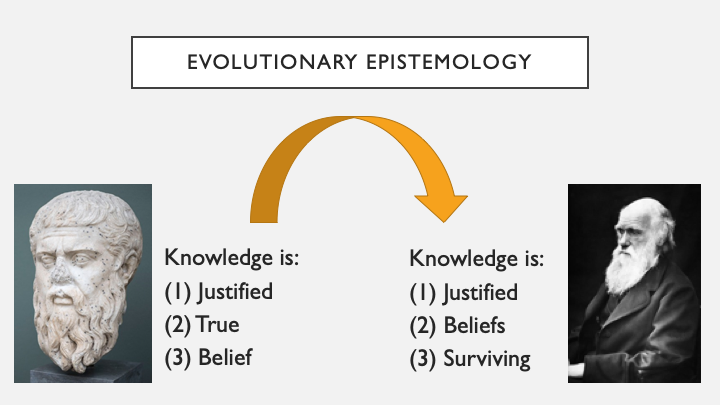

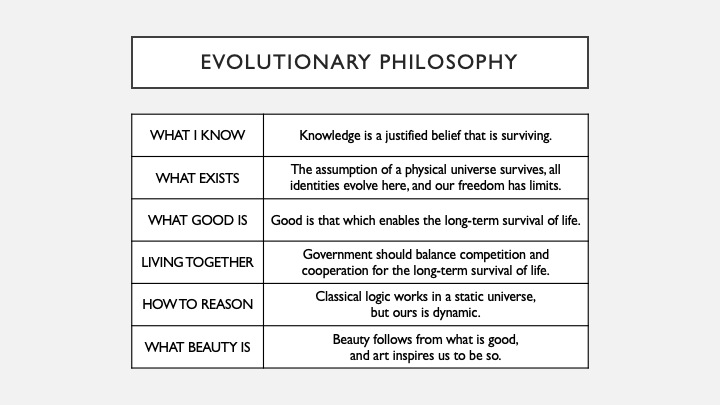

From an evolutionary perspective, though, this seems obvious. For something to be True with a capital T—eternally and always True—you’d need to find an eternally stable and known thing in the universe. But as Darwin and others showed us, the universe moves and changes, and perhaps more importantly, we cannot know what the future may bring. And so, philosophically speaking, we can’t be 100% sure that anything we claim to know will ever stand the test of time as being True.

That leads us to define knowledge as Justified, Beliefs, that are Surviving. And when I say surviving, I don’t just mean these beliefs are existing in someone’s head somewhere; I mean that they’re capable of surviving our best rational tests. Justified beliefs shouldn’t be discarded just because we can’t be sure that they are True. They should only be replaced when we find even better justified beliefs. And since it seems like this is something that will always continue to happen, we should say that our knowledge will continue to evolve too.

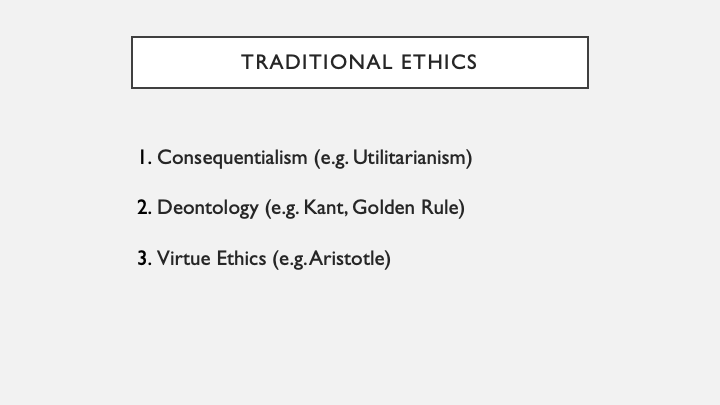

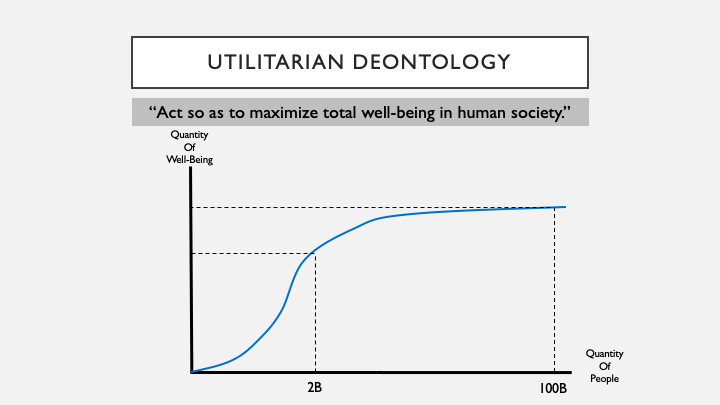

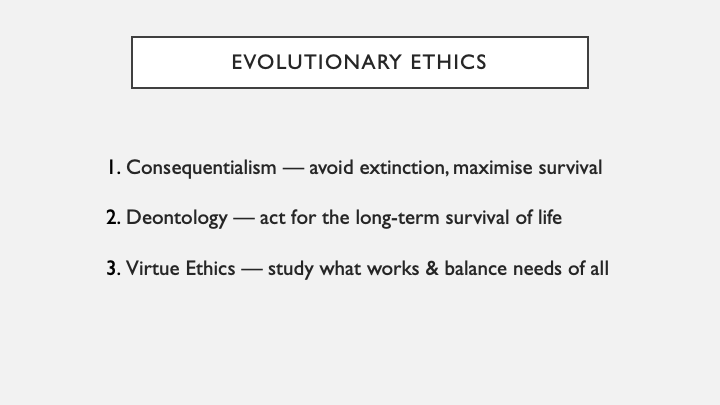

- The first is consequentialism, which, just as the name implies, tries to determine if our actions will have good or bad consequences. Utilitarianism is the most famous example of this, and it’s one that the online course said is often appealing to humanists.

- The second traditional camp is deontology, or rule-based ethics. People in this camp look for hard and fast rules to govern our actions. Rules such as the Ten Commandments, the Golden Rule, or Kant’s categorical imperative.

- Finally, the last camp of virtue ethics traces back to Aristotle who tried to find character traits that are always virtuous in and of themselves.

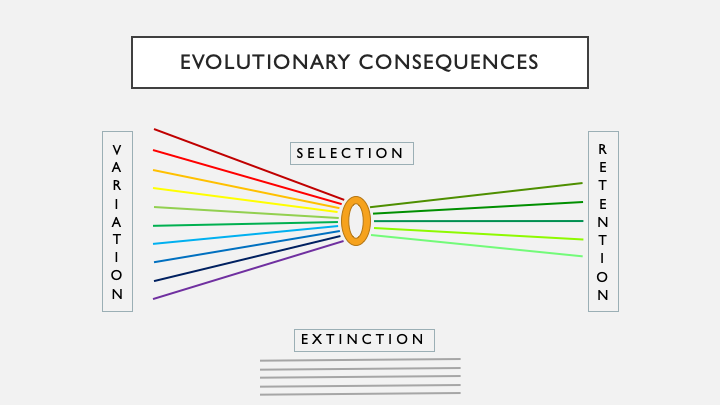

So, there may be a few different selection processes—natural selection, sexual selection, multilevel group selection, and even rational selections of cultural memes—but after any one of them, there are only two possible outcomes in any evolutionary process. Retention……or extinction. Unless you believe in afterlives, that’s all there is. And most of us know which side of that equation we’d like to end up on.

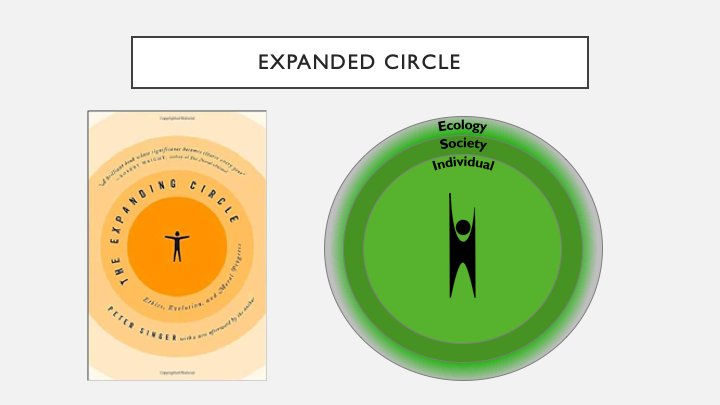

Now I think this is a step in the right direction, but by giving everyone equal consideration, Singer gave us no way to judge between competing interests. Which is more important, for example? My economic livelihood, or the life of a fish? Singer may have brought more beings into our moral conversation, but he still left us squabbling between various circles of insiders and outsiders.

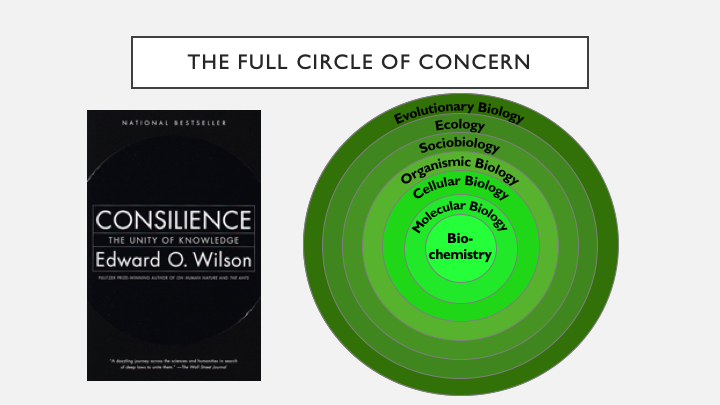

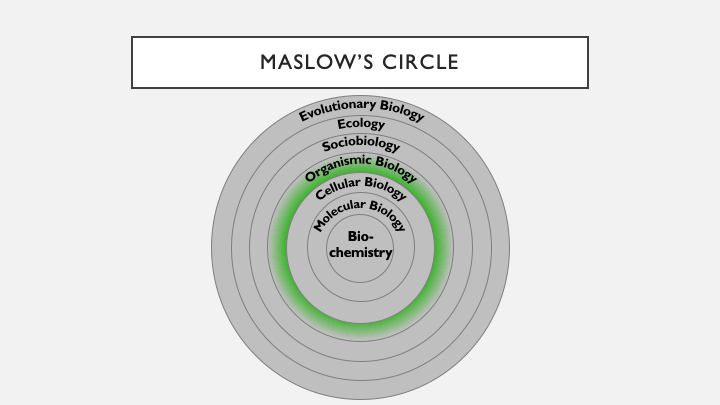

So, this picture now contains all of the major fields of biology, and therefore it can act as a guide for how to study or care about all of the life that has ever existed or ever will. And that brings me to what I think is the ultimate evolutionary consequence that we have to consider. No matter what squabbles we have, in to between any of these individual circles, the most important overriding goal that rises about everything is that we want all of this to continue. We want the entire project of life to keep going. To fail at that goal would mean universal death. And once we agree that that consequence ought to be avoided, then these sciences can start to give us a list of what life needs in order to continue its journey. So, what are some of these needs?

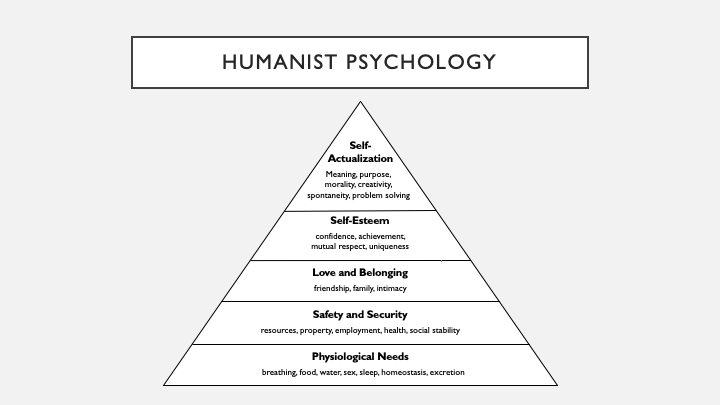

The biggest takeaway I found from this whole exercise was just how interdependent all of these spheres are. Our own Maslow needs, for example, can never be met if we don’t have good societies, productive ecosystems, and enough time to adapt to any changing evolutionary conditions. And all of these are only possible if the biochemistry and other internal processes are healthy too. In fact, since life is only as strong as its weakest link, we have to look out for the health and well-being of each and every level within all seven spheres of biology. Finding the right balance here is the key to understanding what life needs in order to continue to survive.

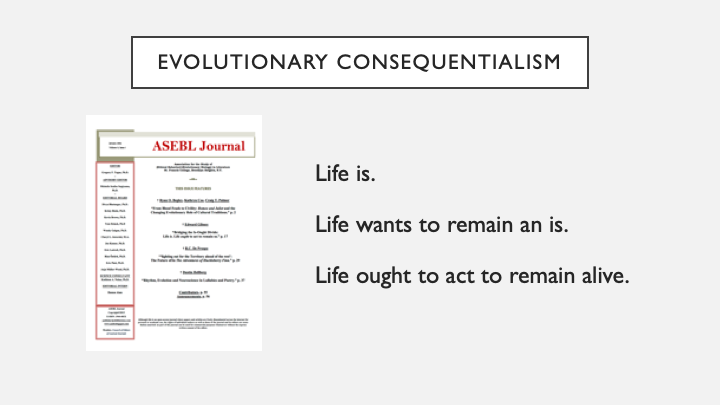

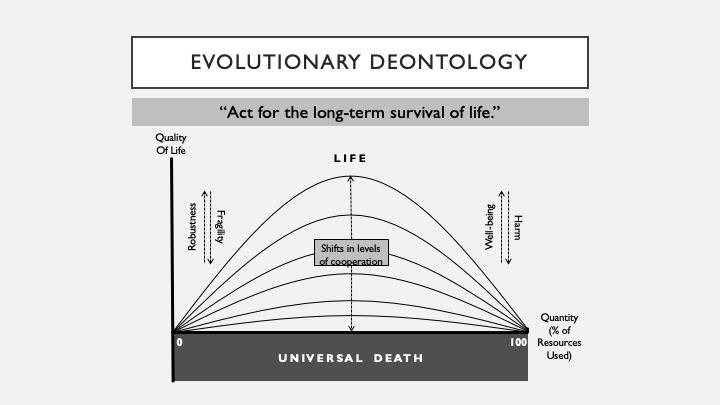

- Life is.

- Life wants to remain an is.

- Therefore, life ought to act to remain alive.

- “Act for the long-term survival of life.”

Scarily, this isn’t far off from what we are already hearing in the news on a daily basis. But this evolutionary view of life, however, shows that we could find a sweet spot where the survival of life can grow more and more robust and less and less fragile, and thus able to continue to try to meet the moral rule shown above. One of the ways we can do this is by creating new curves on this chart, which I say comes from shifts in levels of cooperation.

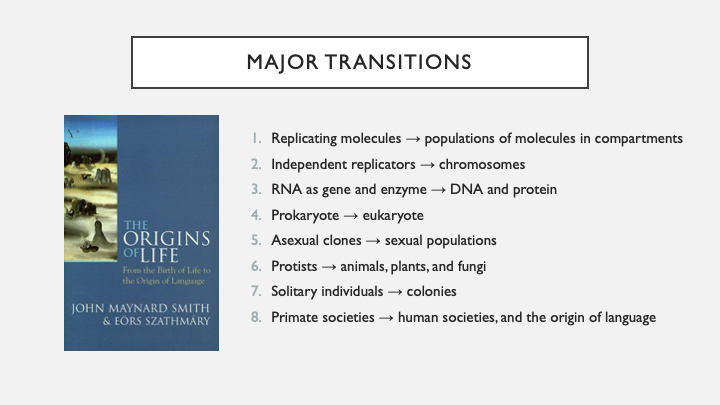

It’s too much to go through the details of the biology in these transitions, but the big takeaway from this book is that each transition occurred when formerly separate and competitive biological elements figured out new ways to join up and cooperate with one another, and begin to evolve together. And that provides a vital clue to our next area.

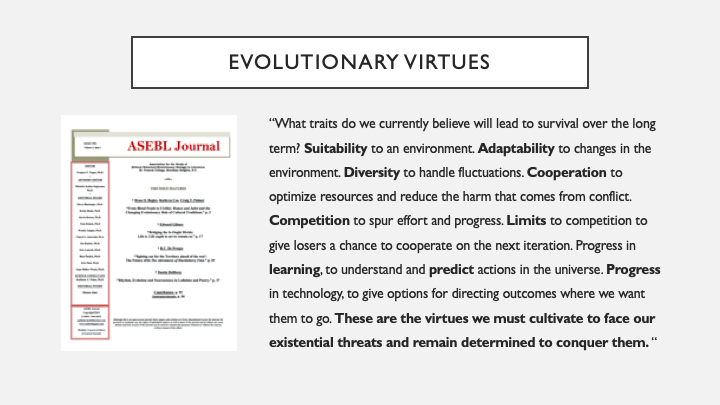

So, in other words, virtues need to be understood in context, as helping us to act towards a consequence or a goal. Well the latest studies in evolutionary biology have uncovered many of the virtues that help us reach our survival goals. These are things such as: suitability to an environment; adaptability; diversity; a balance between cooperation and competition; and growth in our learning and progress so we can predict changes in our environment and respond accordingly. As I said at the end of my journal article, “These are the virtues we must cultivate to face our existential threats and remain determined to conquer them.”

Note that this is where we have learned to avoid the problems of past attempts at evolutionary ethics—from things such as eugenics and Social Darwinism. Proponents of those ideas may have grasped the consequences and some of the rules of evolution, but not the virtues that actually succeed. It turns out that nature isn’t always “red in tooth and claw.” And the survival of the fittest, is actually the survival of the most adaptive and cooperative.

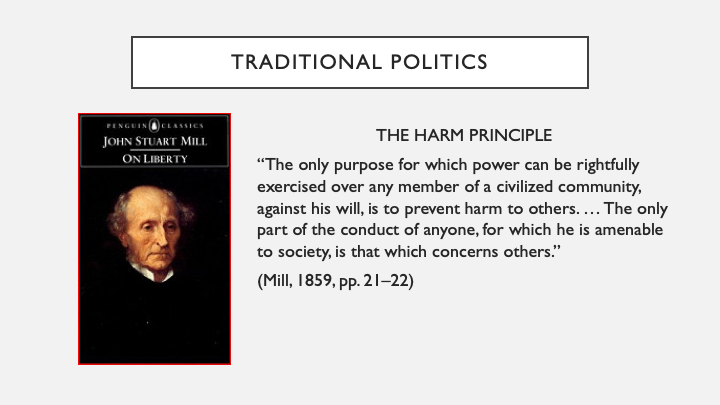

I mentioned earlier that the humanist course talked a lot about the harm principle and how they use that to justify their campaigns for secular societies and human rights. So, this is a really important idea. It was first defined in full by John Stuart Mill in his book On Liberty, which was published in 1859, but that built on earlier work from Utilitarian philosophers such as John Locke and Jeremy Bentham. Altogether, their ideas were very influential for the Bills of Rights and Constitutions in England, America, and France, which were then copied or imitated in liberal democracies all around the world. Let me read a bit from the original definition just to bring home what it’s really all about. The harm principle says:

- “The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. … The only part of the conduct of anyone for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others.”

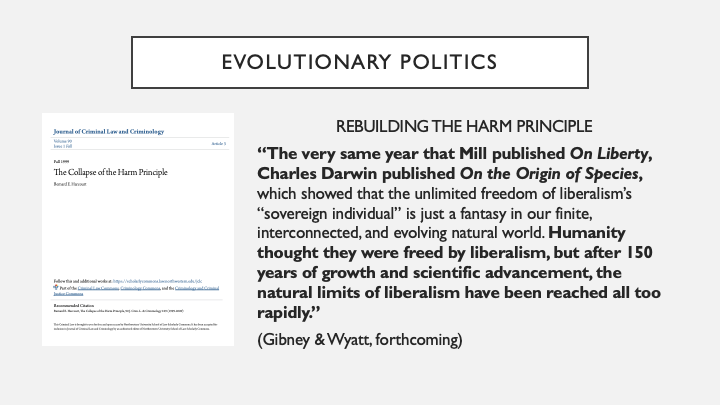

My wife (Tanya) and I are actually working on a paper right now to try and address this by using my evolutionary definition of harm to rebuild the harm principle. Let me just read something quickly from that paper. We note that,

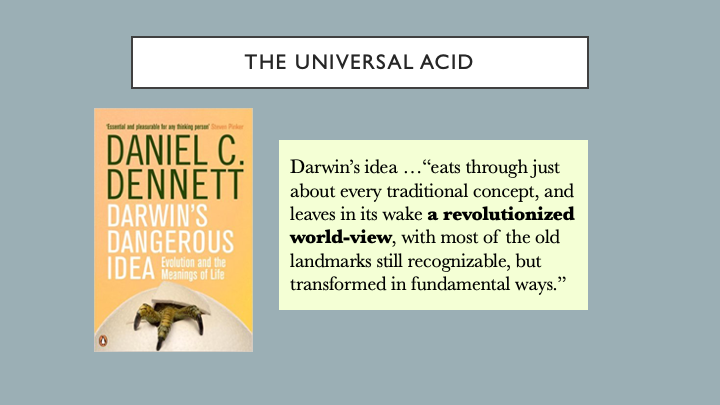

- “The very same year that Mill published On Liberty, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, … Humanity thought they were freed by liberalism, but after 150 years of growth and scientific advancement, the natural limits of liberalism have been reached all too rapidly.”

For many more details on this, you can actually read my first novel, Draining the Swamp, which is about a young idealist who goes to Washington DC and tries to improve government. But for the purposes of this talk, I just want emphasize the point that the harm principle needs to be rebuilt in order for our politics to work properly.

In short, the way that I deal with this is to note that if a situation is accepted as static and perfectly understood, then yes, something can be considered true or false within that situation. But as soon as things start to move and change and evolve, then all bets are off about any truth declarations.

If anyone really wants to discuss this further, we can happily go off and get way down in the weeds on it. As long as the rest of us just agree to use reason and be rational with our logical arguments though, then I think that’s enough for us to be able to move on.

- “The experience of beauty is one of the ways that evolution has of arousing or sustaining interest in order to encourage us towards making the most adaptive decisions for survival and reproduction.”

A lot more could be said about this quote, but I just want to make one point about it. And that is that, although “the experience of beauty” may indeed be subjective and in the eye of the beholder, we now all know a lot more about “making the most adaptive decisions for survival.” And so, I think our understanding of what is beautiful ought to change accordingly.

- I now know not to use the word Truth in any rigorous discussions. And I think we ought to have even more humility about what we think we know.

- I agree that this physical universe is all we’ve detected, and so we ought to live this one life as well as possible.

- I would advocate for the widest possible circle of moral concern, as that gives us an objective definition of good, which can help guide us through our moral dilemmas.

- In politics, we should not only recognize but emphasize that our freedom has natural limits that we have to respect. And we could have positive ethical goals for society too, rather than simply stepping back and saying, “just don’t hurt each other.”

- When logically examining an issue, I try to understand if it is static or dynamic. And in the long run, it’s always dynamic.

- And finally, I too think that we humanists can experience beauty, awe, and purpose, but by focusing on the flourishing of all of life. We may only be one small part of that grand circle, but for now we seem to be privileged to be the only part that understands all of this. And at the risk of getting emotional and squishy about this, I think that’s a beautiful position to be in.

And on that note, I’ll stop and say thank you for [reading], and I look forward to your questions [in the comment section below). Thank you.