A few days into this coronavirus lockdown, I stumbled across an app called Kanopy that lets you log into it using your local library account, and then watch stuff online that you could normally check out of your library. All for free! It's such a great idea. As it happens, my wife's university library account also gave us free access to The Great Courses, which is a real treasure trove of university-level lectures. For reasons I don't need to go into now, I started watching a class called An Introduction to Formal Logic by Professor Steven Gimbel of Gettysburg College. Last night, I made it through lesson 7 on inductive reasoning. (Quick recap: deductive reasoning narrows down from a big rule to small facts, while inductive reasoning grows out from small observances to general rules. Of course, the problem of induction is well known as "the glory of science and the scandal of philosophy.")

Towards the end of this lecture, Gimbel went over the difference between using inductive reasoning for a theory versus using it for a hypothesis. This ended up being one of the best passages I've seen for explaining why Darwin's great idea is called the theory of evolution rather than the fact of evolution. This will also come in handy for anyone who wants to put together a theory of consciousness. Enjoy.

--------------------------------------------

Take Newton’s theory of gravity, which is comprised of three laws: 1) the law of inertia; 2) the force law; and 3) the action-reaction law. Put them together, and you have a full theory of motion. But what we have here are three general propositions, not specific observable claims. These general laws are then combined to form a system from which we can derive specific cases by plugging in the conditions of the world.

These proposed laws of nature, which function as the axioms of the theory, should not be confused with hypotheses. Hypotheses are proposed individual statements of possible truth. They are more specific than the axioms, and we get evidence for them individually. The axioms work together as a group. We may be able to derive hypotheses when working within the theory, but the parts of the theory themselves are not hypotheses.

For example, a hypothesis would be, “If I drop a 10-pound bowling ball and a 16-pound bowling ball off the roof of my house, they will land at the same time." I could test this with a ladder and two bowling balls. Hypotheses are open to such direct testing. The purported laws of nature in Newton's theory, however, are different. Consider Newton’s First Law. If I have an object, and there’s no external force applied to it, then it will move in a straight line at a constant speed. At first glance, this seems like it should be just as testable as the hypothesis about the bowling ball. But the problem is that there can be no such object without an external force applied to it! As soon as there’s any other object in the universe, the object we're examining would feel the pull of gravity, which is an external force. So, Newton’s law of inertia, a vital part of his theory of motion, holds for no actual object. If we treat it like we do hypotheses, it would be kind of like having a biological law about unicorns. So, we have to have different inductive processes for hypotheses and for theories.

[ Karl Popper gave us the idea that hypotheses must be falsifiable. Hypotheses are tested using independent and dependent variables, i.e. the things we adjust and the things we measure.]

What about theories? Here, the philosopher Hans Reichenbach drew a distinction between discovery and justification. What this distinction has come to mean is that there is a difference between the context in which scientists come up with their theories, and the context in which they provide good reasons to believe those theories are true. The context of discovery is genuinely thought to be free. There’s no specific logic of discovery, no turn-the-crank method for coming up with scientific theories. The great revolutionaries are considered geniuses because they were able to not only think rigorously, but also creatively in envisioning a different way the world could work. There’s no logic that tells scientists what to consider when coming up with new theories.

While there’s no set method, surely there is induction in there somewhere. Scientists are working from their experiences and their data. They have a question about how a system works, they consider what they know, and they make inductive leaps. They look for models and analogies where the system could be thought to work like a different system that is better understood. So, while there’s no set means of using induction in the context of discovery, it usually is playing some kind of role.

The most important place in scientific reasoning that we find induction is in the context of justification. Once a theory has been proposed, why should we believe it? Theories are testable. They have effects, results, and predictions that come from them. These observable results of a theory are determined deductively. That is, if a theory is true, then, in some given situation, let's say that observable consequence O should result. We go to the lab, set up the situation, and see if we observe O as expected. If not, then the theory has failed, and, as it stands, it is not acceptable. It will either have to be rejected or fixed. But, if the theory says to expect O, and we actually do observe O, now we have evidence in favour of the theory. That evidence is inductive. It may be that theory T1 predicts O, but there will also be other theories, like T2, which is different from T1, which is also supported by O. As such, neither T1 nor T2 are certain. (To the degree that inductive inferences could be anyway.)

How then do we go from supporting evidence (which makes a theory more likely), to conclusive evidence (which makes a theory probably true)? We need lots of evidence. We also need evidence of different types. It’s good for a theory if it can account for everything we already know. We call this retrodiction. This is particularly true if everything we knew was previously unexplained. For example, before Einstein’s theory of general relativity, we knew that not only did Mercury orbit the Sun, but each time Mercury would make it around the Sun, the farthest point in its orbit would be in a different place. In other words, Mercury did not make the same exact trip around the Sun every time. But we had no idea why! Once Einstein gave us a new theory of gravitation, this effect was naturally explained. The fact that it solved the mystery was taken as strong inductive evidence.

Even better than explaining what we already know, prediction is also taken as strong evidence. Newton’s theory predicted that a comet would appear around Christmastime in 1758. When this unusual sight appeared in the sky on Christmas day, the comet (named for Newton’s close friend Edmund Halley) was taken as very strong evidence for his theory.

Beyond even prediction, the best evidence for a theory can bring forth what William Whewell termed consilience. Whewell was a philosopher of science, an historian of science, and also a scientist. In fact, he was the person who coined the term scientist. Consilience is when a theory that is designed to account for phenomena of type A, turns out to also account for phenomena of type B. If you set out to explain one thing, and are also able to explain something completely different, then that is extremely strong evidence that your theory is probably true.

The reigning champ in this realm is Darwin’s theory of evolution. It accounts for biodiversity. It accounts for fossil evidence. It accounts for geographical population distribution. There’s just a huge range of all sorts of observations that evolution makes sense of. This is stunning, and stands as extremely strong evidence for its likely truth.

This consilience is no accident. In his college days, Darwin was a student of Whewell’s. When he later began to develop his ideas, Darwin was extremely nervous about them. He knew how explosive his view was, so he spent many, many years accumulating a broad array of different sources of evidence in order to demonstrate his theory’s consilience. Some people today contend that evolution is not proven. Well of course it isn’t! The only things that are proven are the results of deductive logic. Darwin’s theory—like everything else in science—is confirmed by inductive logic, which never gives proof, but which offers high probability, and thereby firm grounds, for rational belief.

--------------------------------------------

What do you think? Does this understanding of a theory help you see how science can actually posit ideas that cannot be tested on their own, yet still help us make sense of the world? Are we ready for a theory of consciousness that uses analogies from things we understand to explain everything we know, make some predictions, and offer a consilient view of a wide variety of observations? And might it fit in with the theory of evolution too? Maybe not 100% ready, but I'm going to sketch out a new theory next time and give this all a go.

--------------------------------------------

Previous Posts in This Series:

Consciousness 1 — Introduction to the Series

Consciousness 2 — The Illusory Self and a Fundamental Mystery

Consciousness 3 — The Hard Problem

Consciousness 4 — Panpsychist Problems With Consciousness

Consciousness 5 — Is It Just An Illusion?

Consciousness 6 — Introducing an Evolutionary Perspective

Consciousness 7 — More On Evolution

Consciousness 8 — Neurophilosophy

Consciousness 9 — Global Neuronal Workspace Theory

Consciousness 10 — Mind + Self

Consciousness 11 — Neurobiological Naturalism

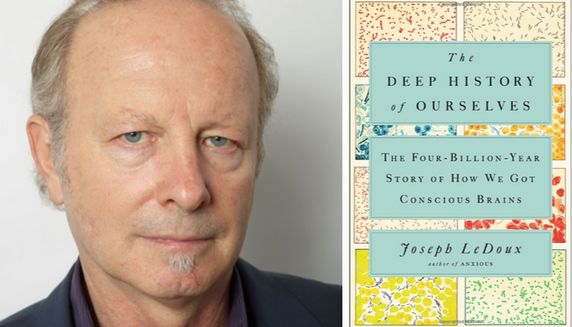

Consciousness 12 — The Deep History of Ourselves

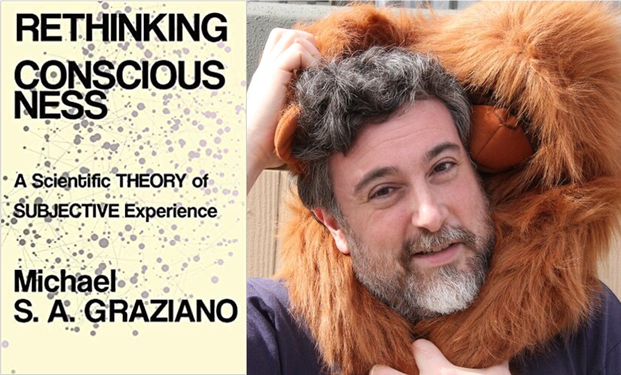

Consciousness 13 — (Rethinking) The Attention Schema

Consciousness 14 — Integrated Information Theory