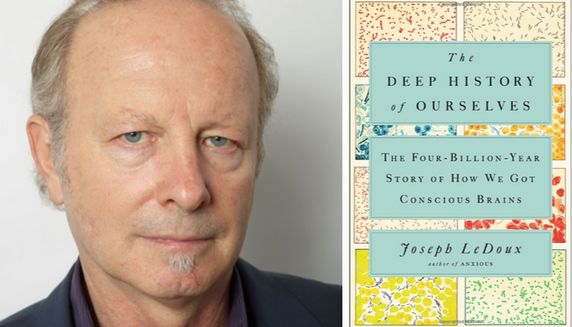

The first interview was with Joseph LeDoux about his book The Deep History of Ourselves: The Four-Billion-Year Story of How We Got Conscious Brains. What a great evolutionary title! LeDoux is a Professor of Neural Science and Psychology at NYU who has spent the last thirty years studying the brain mechanisms of fear and emotional memory. He's also the guitarist and songwriter for a funky band called The Amygdaloids who gave us the hep-cat, jazzy, yet informative little number Fearing. (Pretty awesome.) For a more straightforward lesson about consciousness, however, here are the highlights from LeDoux's interview with Dr. Campbell:

- Higher-order representations is the category LeDoux prefers from among the 20 different theories of consciousness.

- How far back in evolution does the ability to detect and respond to danger go? Other nonhuman animals do this. Even bees. But it’s much older still. Protozoa like paramecia or amoeba do it. Even bacteria do. In fact, it goes all the way back to the beginning of life.

- It's not just detecting danger either — incorporating nutrients, balancing fluids and ions, thermoregulation, reproduction for the species to survive — all of these behaviors exist in animals, but also in single-cell microbes. Value / valence / affect has also been present since the beginning of life (e.g. bacteria swim toward or away from things).

- So, behavior and even learning and memory do not require nervous systems.

- When we do those things, we have subjective experiences about them, but those subjective experiences are not essential to the actions.

- What is the relationship between behavior and consciousness? We see behavior in others so we attribute the same thoughts and feelings that we do. This makes sense for other human brains, but it is more and more dissimilar for other brains.

- When we detect danger, we feel fear. But that may not always be the case. Split brain cases show one side getting a signal, the body acts, but then the other side can’t say why.

- I hypothesized that emotional systems could generate non-conscious behaviors. I was able to trace the pathways through the amygdala to do this. Other research showed the amygdala is involved in implicit / non-conscious memories as opposed to conscious memories about detecting and responding to danger. I used this model for memories and applied it to emotions—i.e. implicit vs. explicit emotions. I thought of conscious explicit emotions as the product of cortical areas. Non-conscious emotions come out of the amygdala. The amygdala doesn’t experience fear; it just produces responses.

- When stimuli are presented to patients, but masked so they can’t detect it consciously, the visual cortex and amygdala are activated and that’s it. When the stimulus is not masked, you get activation in the visual cortex, the amygdala, and the prefrontal cortex as well. ... In order to be conscious of an apple, it not only needs to be represented in your visual cortex, it needs to be re-represented, which involves the prefrontal cortex. ... So, the prefrontal cortex is emerging as an important area in the consolidation of our conscious experiences into what they are.

- In other words, the ability to respond to and detect danger may be as old as life, but the feeling of fear may be a much more recent addition.

- [Here's my 1st crazy idea.] What came first was cognition not emotion. I’m defining cognition as the ability to form internal representations of stimuli and to perform behaviors based on those representations. Cues are enough to stimulate the behavior independent of the presence of the stimuli themselves. The representation alone is enough to guide the behavior. That capacity exists in invertebrates, and on into all vertebrates, e.g. fish and reptiles. When you get to mammals, you have a much more complex form of cognitive representation, where it begins to look deliberative, i.e. the ability to form mental models that can be predictive of things not existing. It’s a much more complicated thing than having a static memory of what was there.

- We assume that because mammals behave in much the same way that we do, they must be experiencing the same things. But the amygdala example of fear gives us some reason to be cautious about that. The short summary is that you should actually assume behavior is unconscious unless proven otherwise.

- In humans, we all know that we have these conscious experiences. In an experiment, we ask, “Can the response in this experiment be explained by a conscious state?” We have to rule out that the response is not coming from a non-conscious state. But we have a vast cognitive unconscious repository of information that allows us to get through the day without having to consciously evaluate everything we do (e.g. speaking grammatically, anticipating what we are looking at before we see it, completing patterns on the basis of limited information). To separate these conscious and non-conscious responses you can do experiments, and these have indeed happened.

- The gold standard for whether a response is conscious or not is whether you can talk about it. This doesn’t mean language and consciousness are identical, just that you have access to the experience to think about it (and we use language to discuss that access with one another). In non-human animal research, that doesn’t exist. It would be good for animals to treat them as if they had conscious experiences, but it’s not a scientific demonstration to watch behavior and say that they do.

- Darwin, when faced with resistance about humans evolving from animals, responded not by saying that people have bestial qualities, but by saying that animals have human qualities. This set the debate on a track that has been difficult to get past. There was tremendous anthropomorphism in the late 19th century. That led to the radical behaviorist movement in psychology where all cognitive experience was eliminated from research. The cognitive revolution brought back the mind, but as an information processing system with inputs being conscious and unconscious. This gave us the “cognitive unconscious”, which is a middle ground between the choice the behaviourists gave us between conscious vs. reflex machines.

- Anthropomorphism may be an important innate human quality, but that doesn’t mean it’s an accurate concept. And maybe we just can’t know either.

- As a brief aside, usages of the limbic system, triune brain, and serial evolution of additive brain functions are all outdated now.

- [Here's my 2nd crazy idea.] Emotions are not initially a product of natural selection. Emotions are conscious experiences constructed by cognitive processes. The possibility then exists that the cognitive abilities that are unique in the human brain might be responsible for those emotions. Maybe emotions came in with the early humans. Maybe they came in as byproducts, or what Stephen J. Gould called exaptations. If this cognitive model is correct, then emotions are based on mental schema (bodies of memories about certain categories of experiences), for example, a fear schema. When in danger, a template is activated. This has implications for medicine to treat emotions. For example, people taking medicine for social anxiety find it easy to go to parties (they are less timid), but they still feel anxious when there. ... Drugs alone won’t be enough to treat problems. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is required in the end.

- A particular human experience is where you know the experience is happening to you. We can’t rule that out in other animals, but neurological evidence suggests that it’s not happening. This "autonoetic consciousness" represents the view of the self as the subject. It enables mental time-travel (i.e. you can review past experiences and possible future states). Other animals can learn from the past, but in a simple way. They can also have shifts in perspectives to those of others, but they don’t have this notion of the self that is part of these experiences. Non-conscious alternatives can always account for the behavior in animals.

- Every person has the same human brain. There are things in our prefrontal cortex, structures (“frontal pole”), and connections that are unique to humans. But mice have their own unique brain area. Other animals may also have their own unique ways of experience. We have to be subtle and not simply say conscious or nonconscious. Consciousness isn’t one thing. There's autonoetic consciousness. There's noetic consciousness (an awareness of facts and the world). Working memory, for example, is very similar in other primates but not other mammals. There's anoetic consciousness, which is a body awareness (i.e. Jaak Panksepp's core consciousness, which is a primitive, almost unconscious level of consciousness). Understanding brain structures and pathways might help us understand what forms of consciousness are possible, even if we can never measure it.

Brief Comments

LeDoux seems to draw a pretty narrow definition around consciousness, but then shows the clear evolutionary history of aspects of consciousness along the way, and really advocates for a more subtle use of the term. I'll present my own subjective labelling system for all this at the end of the series (because we sure could use another!), but hopefully the contents of facts within that system will be uncontroversial, and they will surely draw on LeDoux's work.

Like Damasio, whose strange inversion was that emotions preceded feelings, LeDoux's first crazy idea is his own inversion, where he says cognition preceded emotion. In one respect, these guys are actually saying the same thing, that the "subjective experience of moods" came last. But Damasio calls that "feelings" while LeDoux calls it "emotion". Clearly there is a split here between the chemical changes that cause behavior, and the subjective experience of these changes, but it's frustrating that the field hasn't settled on consistent terminology yet of what's on each side of this divide, which makes discussing these ideas so much more difficult. (It's another good example of the value that philosophers of science can be to scientists.)

What I don't see from LeDoux in this crazy idea is any discussion of affect or value. The amygdala may be able to non-consciously produce behavior in response to stimuli. It may even learn to do this differently throughout a lifetime. But it could only do so (successfully) by valuing some responses positively and others negatively. Since LeDoux does state that valence goes all the way back to the beginning of life, maybe he just lumps this in as part of "cognition", which then looks even more like Damasio's "emotions", which both men claim came first during evolution.

As for LeDoux's second crazy idea, it's hard for me to see how he can advocate for the need for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to regulate emotional feelings, but then suggest that these emotional feelings weren't initially a product of natural selection. Perhaps it comes down to how narrowly one defines "initially" but if CBT can improve one's life, then it sure seems plausible that the advent of emotional feelings would have provided an advantage that could have been selected for. Maybe I'm just being overly critical of anyone quoting Gould, though, since I'm of the opinion that he generally lost the Darwin Wars.

Finally, as an evolutionary thinker, I note that LeDoux offers a really good critique of anthropomorphism and the role that Darwin may have played in going down that path. Such attributions to non-human animals can obviously be taken too far. But so can anthropodenial (as Franz de Waal has coined it) for the people who go in the other direction and tout human exceptionalism. I really appreciate LeDoux's openness about this and his search for hard evidence. I also like his recognition that it would be better for us to treat animals as if they had valuable internal experiences, since we are currently faced with the barrier that we may never know about that. So, one form of human exceptionalism that exists may just be that we are profoundly ignorant of life....except for what we can know about ourselves. Perhaps it would be better to pay attention sometimes to that wide ignorance rather than any narrow knowledge.

What do you think? Are LeDoux's two crazy ideas really that crazy? What else jumped out at you from his deep history of ourselves?

--------------------------------------------

Previous Posts in This Series:

Consciousness 1 — Introduction to the Series

Consciousness 2 — The Illusory Self and a Fundamental Mystery

Consciousness 3 — The Hard Problem

Consciousness 4 — Panpsychist Problems With Consciousness

Consciousness 5 — Is It Just An Illusion?

Consciousness 6 — Introducing an Evolutionary Perspective

Consciousness 7 — More On Evolution

Consciousness 8 — Neurophilosophy

Consciousness 9 — Global Neuronal Workspace Theory

Consciousness 10 — Mind + Self

Consciousness 11 — Neurobiological Naturalism