John Stuart Mill's book Utilitarianism first appeared as a series of three articles published in Fraser's Magazine in 1861, but the articles were collected and reprinted as a single book in 1863. To this day, it remains:

"the most famous defense of the utilitarian view ever written and is still widely assigned in university ethics courses around the world. Largely owing to Mill, utilitarianism rapidly became the dominant ethical theory in Anglo-American philosophy. ... Though heavily criticized both in Mill's lifetime and in the years since, Utilitarianism did a great deal to popularize utilitarian ethics and was the most influential philosophical articulation of a liberal humanistic morality that was produced in the nineteenth century."

In this small 44-page book, Mill's theory of morality is grounded in a particular “theory of life…namely, that pleasure, and freedom from pain, are the only things desirable as ends.” Mill believed that pleasure was equal to happiness, and that it was "the only thing humans do and should desire for its own sake. Since happiness is the only intrinsic good, and since more happiness is preferable to less, the goal of the ethical life is to maximize happiness."

This was published a couple of years after Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859), but Mill had obviously not digested that work. Pleasure or freedom from pain are NOT ends in themselves, they are means towards something else. They are signposts for how to act towards survival! And this is the fatal flaw in utilitarianism. Pleasure / happiness is not desired for its own sake. One can quite easily pleasure themselves (not a euphemism) directly into the ground unless they take some kind of long-term view that allows them to balance pleasure and pain towards....survival. Mill should have been able to see this flaw. After all, he argued that:

"traditional moral rules such as 'Keep your promises' and 'Tell the truth' have been shown by long experience to promote the welfare of society. Normally we should follow such 'secondary principles' without reflecting much on the consequences of our acts. As a rule, only when such second-tier principles conflict is it necessary (or wise) to appeal to the principle of utility directly."

But this "principle of utility" is clearly just another "secondary principle" since it often comes into conflict with itself. Happiness / pleasure cannot be used as a guide on its own because there are all sorts of pleasures for all sorts of reasons, many of which need to be followed and many of which need to be ignored. Therefore, there must be a more fundamental principle to guide wise judgment about these types of pleasure. Mill should have seen this, but instead of finding a guiding principle, he just tried to assert what "higher and lower pleasures" are. That brings us to this week's thought experiment.

--------------------------------------------------

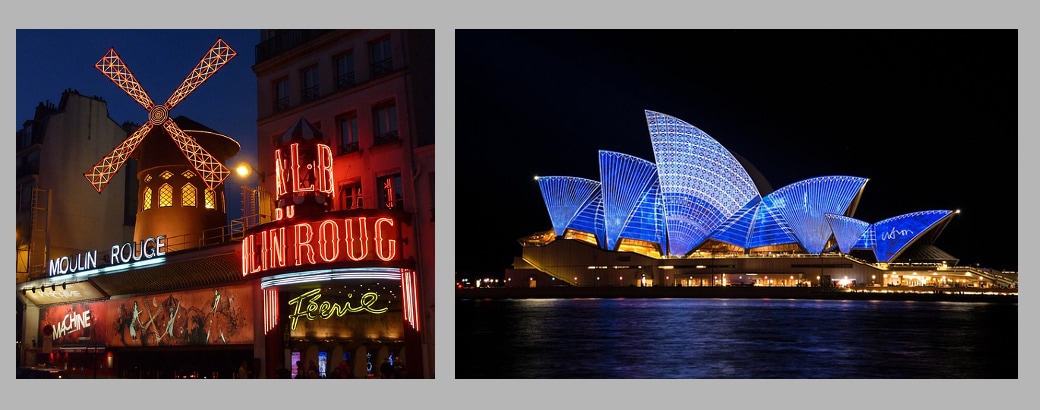

It's just typical — you wait years for a career breakthrough then two opportunities turn up at once. Penny had finally been offered two ambassadorial positions, both at small South Sea Island states of similar size, geology, and climate. Raritaria had strict laws which prohibited extra-marital sex, drink, drugs, popular entertainments and even fine food. The country permitted only the "higher pleasures" of art and music. Indeed, it actually promoted them, which meant it had world-class orchestras, opera, art galleries, and "legitimate" theatre.

Rawitaria, by contrast, was an intellectual and cultural desert. It was nonetheless known as a hedonists' paradise. It had excellent restaurants, a thriving comedy and cabaret circuit, and liberal attitudes to sex and drugs.

Penny did not appreciate having to choose between the higher pleasures of Raritaria and the lower ones of Rawitaria, for she enjoyed both. Indeed, a perfect day for her would combine good food, good drink, high culture, and low fun. Choose she must, though. So, forced to decide, which would it be? Beethoven or Beef Wellington? Rossini or Martini? Shakespeare or Britney Spears?

Source: Utilitarianism by John Stuart Mill (1863).

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 250.

---------------------------------------------------

In Baggini's discussion of this thought experiment, he writes:

In which of these odd little countries is it easier to live a good life? You might think that it is merely a question of preference. ... If it is simply a matter of taste and disposition, however, then why do the higher pleasures attract government subsidies when the lower ones are more often than not heavily taxed? If the pleasure we gain from listening to a Verdi opera is worth no more than the pleasure of listening to Motörhead, then why aren't seats at rock gigs subsidised as much as those at the Royal Opera House? ... The suspicion is that this is just preference, snobbery, or elitism dressed up as an objective argument. The problem exercised John Stuart Mill, the utilitarian philosopher, who thought that the goal of morality was to increase the greatest happiness of the greatest number. The problem he faced was that his philosophy seemed to value a life full of shallow and sensual pleasures above that of a life with fewer, but more intellectual ones. The contented cat would have a better life than a troubled artist. The solution was to distinguish between the quality as well as the quantity of pleasure. A life full only of lower pleasures was worse than one with even just a few higher ones. This still leaves the problem of justification: why is it better? Mill proposed a test. We should ask what competent judges would decide. Those who had tasted both higher and lower pleasures were the best placed to determine which were superior. And as the labels "higher" and "lower" suggest, he knew how he thought they would choose.

Now we see, however, that the choice is a false one. Pleasure is not an intrinsic end goal, so higher and lower pleasures do not exist intrinsically. Sensual pleasures can sometimes lead to survival, and sometimes lead toward extinction. Intellectual pleasures can also lead us in either direction. At the end of my blog post on John Stuart Mill, I pointed out that "there is a fatal flaw in utilitarianism in that by proclaiming the endpoint of morality as "maximizing happiness for the greatest number," it can too easily lead to overpopulation and a crashing of the planet's ecosystems [which is known as the repugnant conclusion] because not enough attention is being paid to the actual objective basis for morality—the long-term survival of life." That goal is no secondary principle. Life can have pleasure or not have pleasure. It cannot have survival or not have survival. If it has no survival, there is nothing left. I discussed this at length in my reply to the repugnant conclusion, but I ended with this:

Welfare, well-being, flourishing, eudaimonia...whatever you want to call it...it does matter, but it is NOT paramount. Survival is paramount, and therefore decisive. You can have all the thriving you want, but only AFTER your morals point life towards survival. If well-being were the ultimate and decisive value, whose well-being would be worth marching everything else to extinction? When an issue A supervenes upon issue B, issue B is more fundamental. The issue A of well-being can only be satisfied if the issue B of existence is met. Survival / existence is the most fundamental attribute we must build our morality upon.

So, Raritaria or Rawitaria? It doesn't really matter. Penny should flip a coin if she has to, but then immediately foster diplomatic relations between the two island nations which leads them both to reorganise their laws around a new fundamental principle based on evolutionary philosophy rather than utilitarianism.