(Warning. I'm sorry this post was several days late, but it deserved a very long response. Settle in.)

This is it — the final thought experiment! I like this as an ending because it doesn't just zoom in on another one of the narrow technicalities of traditional philosophy—we've already done enough of that! Rather, I think this widens the scope to consider a broad societal ill and asks us whether we can put everything we've learned to good use in order to properly diagnose the problem and then prescribe some useful solutions. In the end, isn't that what philosophy should really be all about? That's certainly why I'm here, so let's get to it.

--------------------------------------------------

Eric was a regular at the Nest café. The quality of the food and drink was unexceptional, but they were remarkably cheap.

One day he asked the manager how she did it. She leaned over and whispered, conspiratorially, "Easy. You see, all my staff are from Africa. They need to survive but can't get regular jobs. So I let them sleep in the cellar, feed them just enough, and give them £5 cash a week. It's great—they work all day, six days a week. With my wage bill so low, I can offer low prices and make handsome profits.

"Don't look so shocked," she continued, reading his reaction. "This suits everyone. They choose to work here because it helps them, I make money, and you get a bargain. Top up?"

Eric accepted. But perhaps this would be his last coffee here. Despite the manager's justification, he felt, as a customer, he would be complicit in exploitation. As he sipped his americano, however, he wondered if the staff would appreciate his boycott. Weren't these jobs and the shelter of the cellar better than nothing?

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 298.

---------------------------------------------------

1.

We could make quick work of this by noting that the Nest café is clearly breaking labor laws and Eric would be wise not to take part in supporting those illegal activities. The cheap justification by the manager that this situation was good for her, her employees, and her customers, is easily batted aside by considering the implications for other stakeholders such as the rest of the job seekers in the town, or other business owners who must compete with this, or considering whether this leads one to believe that any other laws (such as food safety) are being ignored too. But, of course, there is more at stake in this thought experiment than just the issues concerned with one specific café. Much more. As I noted in the post last Monday, Baggini said of this:

You don't have to be a militant anti-capitalist to recognise that everyone who lives in a developed country is essentially in the same position as Eric. We import comparatively cheap goods because those producing them work for a pittance. And if we know this yet carry on buying, we are helping to maintain the situation. Do not be fooled by the superficial differences. Eric is closer to the cheap labour than we are, but geographical proximity is not ethically significant in this case. You don't cease to exploit someone simply by putting miles between you. Nor is the illegality of the café staff the issue. Simply imagine a country where such employment practices are permitted. ... If Eric is wrong to help feather the Nest, we are wrong to buy from businesses that treat the people at the other end of their supply chains in the same way. This is a very troubling conclusion, for it makes almost every one of us complicit in exploitation.

Troubling indeed, as thanks to rampant globalization we probably all spend money every week on something small or large that has come through the supply chain from far off countries with very different laws and customs. But is that really exploitation? In the go-go 1990's, after the fall of the Soviet Union, international free trade was championed as not only a way to raise global GDP and "lift all boats" out of poverty, but the New York Times columnist Tom Friedman wrote an op-ed in 1997 titled "The Globalutionaries" that showed how cultural values could be improved via globalization as well. Among other things, Friedman profiled capitalist democratic revolutionaries in Indonesia who were fighting against their dictator in a new non-violent way.

Their strategy is to do everything they can to integrate Indonesia into the global economy on the conviction that the more Indonesia is tied into the global system, the more its government will be exposed to the rules, standards, laws, pressures, scrutiny and regulations of global institutions, and the less arbitrary, corrupt and autocratic it will be able to be. ... Globalization has many dark sides, from environmental degradation to widening the gap between rich and poor, but what you see in Indonesia is its most important upside -- the ability to generate pressure on autocratic regimes when no domestic space is available.

Devotees of Peter Singer's effective altruism might be happy with these consequences of benefits being sent abroad, but it's not only (or even usually) their money and jobs that are being given away. The "widening gap between rich and poor" that Friedman mentioned 20 years ago has seemingly now ballooned to the point where that dark side of globalization is threatening to blot out our own shining democratic values and allow autocratic regimes to take root in the West. This is a very complex issue though, and to understand all the background on this more deeply, I highly recommend the long-read article in The Guardian last week titled "Globalization: the rise and fall of an idea that swept the world." If you don't want to pause to read the whole article right now, here are some important passages. (And if you don't need any recaps, skip to the end of the asterisks.):

*****

The future of economic globalization, for which the Davos men and women see themselves as caretakers, had been shaken by a series of political earthquakes. “Globalization” can mean many things, but what lay in particular doubt was the long-advanced project of increasing free trade in goods across borders. The previous summer, Britain had voted to leave the largest trading bloc in the world. In November, the unexpected victory of Donald Trump, who vowed to withdraw from major trade deals, appeared to jeopardize the trading relationships of the world’s richest country. Forthcoming elections in France and Germany suddenly seemed to bear the possibility of anti-globalization parties garnering better results than ever before. The barbarians weren’t at the gates to the ski-lifts yet – but they weren’t very far.

Christine Lagarde, the head of the International Monetary Fund, called for a policy hitherto foreign to the World Economic Forum: “more redistribution”. After years of hedging or discounting the malign effects of free trade, it was time to face facts: globalization caused job losses and depressed wages, and the usual Davos proposals – such as instructing affected populations to accept the new reality – weren’t going to work. Unless something changed, the political consequences were likely to get worse.

People in the rich countries would either have to accept lower wages to compete, or lose their jobs. But no matter what, the goods they formerly produced would now be imported, and be even cheaper. And the unemployed could get new, higher-skilled jobs (if they got the requisite training). Mainstream economists and politicians upheld the consensus about the merits of globalization, with little concern that there might be political consequences.

Back then, economists could calmly chalk up anti-globalization sentiment to a marginal group of delusional protesters, or disgruntled stragglers still toiling uselessly in “sunset industries”. These days, as sizable constituencies have voted in country after country for anti-free-trade policies, or candidates that promise to limit them, the old self-assurance is gone. Millions have rejected, with uncertain results, the punishing logic that globalization could not be stopped. The backlash has swelled a wave of soul-searching among economists, one that had already begun to roll ashore with the financial crisis. How did they fail to foresee the repercussions?

In the heyday of the globalization consensus, few economists questioned its merits in public. But in 1997, the Harvard economist Dani Rodrik published a slim book that created a stir. Appearing just as the US was about to enter a historic economic boom, Rodrik’s book, Has Globalization Gone Too Far?, sounded an unusual note of alarm.

Since the 1980s, and especially following the collapse of the Soviet Union, lowering barriers to international trade had become the axiom of countries everywhere. Tariffs had to be slashed and regulations removed. Trade unions, which kept wages high and made it harder to fire people, had to be crushed. Governments vied with each other to make their country more hospitable – more “competitive” – for businesses. That meant making labour cheaper and regulations looser, often in countries that had once tried their hand at socialism, or had spent years protecting “homegrown” industries with tariffs.

These moves were generally applauded by economists. After all, their profession had long embraced the principle of comparative advantage – simply put, the idea that countries will trade with each other in order to gain what each lacks, thereby benefiting both. In theory, then, the globalization of trade in goods and services would benefit consumers in rich countries by giving them access to inexpensive goods produced by cheaper labour in poorer countries, and this demand, in turn, would help grow the economies of those poorer countries.

But the social cost was high – and consistently underestimated by economists. Since the 1970s, lower-skilled European and American workers had endured a major fall in the real value of their wages, which dropped by more than 20%. Workers were suffering more spells of unemployment, more volatility in the hours they were expected to work.

While many economists attributed much of the insecurity to technological change – sophisticated new machines displacing low-skilled workers – [the dissenting Harvard economist] Rodrick suggested that the process of globalization should shoulder more of the blame. It was, in particular, the competition between workers in developing and developed countries that helped drive down wages and job security for workers in developed countries. Over and over, they would be held hostage to the possibility that their business would up and leave, in order to find cheap labour in other parts of the world; they had to accept restraints on their salaries – or else.

In 1999, the [anti-globalization] movement reached a high point when a unique coalition of trade unions and environmentalists managed to shut down the meeting of the World Trade Organization in Seattle. ... In January 2000, [Nobel prize winning economist] Paul Krugman used his first piece as a New York Times columnist to denounce the “trashing” of the WTO, calling it “a sad irony that the cause that has finally awakened the long-dormant American left is that of – yes! – denying opportunity to third-world workers”.

Arguments against the global justice movement rested on the idea that the ultimate benefits of a more open and integrated economy would outweigh the downsides. “Freer trade is associated with higher growth and … higher growth is associated with reduced poverty,” wrote the Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati in his book In Defense of Globalization. “Hence, growth reduces poverty.” No matter how troubling some of the local effects, the implication went, globalization promised a greater good.

In the wake of the financial crisis, the cracks began to show in the consensus on globalization, to the point that, today, there may no longer be a consensus. ... Erstwhile supporters now concede, at least in part, that it has produced inequality, unemployment, and downward pressure on wages. Nuances and criticisms that economists only used to raise in private seminars are finally coming out in the open.

A few months before the financial crisis hit, Krugman was already confessing to a “guilty conscience”. In the 1990s, he had been very influential in arguing that global trade with poor countries had only a small effect on workers’ wages in rich countries. By 2008, he was having doubts: the data seemed to suggest that the effect was much larger than he had suspected.

In an infamous World Bank memo from 1991, [Larry Summers] held that the cheapest way to dispose of toxic waste in rich countries was to dump it in poor countries, since it was financially cheaper for them to manage it. “The laws of economics, it’s often forgotten, are like the laws of engineering,” he said in a speech that year at a World Bank-IMF meeting in Bangkok. “There’s only one set of laws and they work everywhere. One of the things I’ve learned in my short time at the World Bank is that whenever anybody says, ‘But economics works differently here,’ they’re about to say something dumb.” Over the last two years, a different, in some ways unrecognizable Larry Summers has been appearing in newspaper editorial pages. More circumspect in tone, this humbler Summers has been arguing that economic opportunities in the developing world are slowing, and that the already rich economies are finding it hard to get out of the crisis. Barring some kind of breakthrough, Summers says, an era of slow growth is here to stay. In Summers’s recent writings, this sombre conclusion has often been paired with a surprising political goal: advocating for a “responsible nationalism”. Now he argues that politicians must recognize that “the basic responsibility of government is to maximize the welfare of citizens, not to pursue some abstract concept of the global good”.

“The opening years of the 20th century were the closest thing the world had ever seen to a free world market for goods, capital, and labour,” writes the Harvard professor of government Jeffry Frieden in his standard account, Global Capitalism: Its Fall and Rise in the 20th Century. “It would be a hundred years before the world returned to that level of globalization.”

Over the course of the 1930s and 40s, liberals – John Maynard Keynes among them – who had previously regarded departures from free trade as “an imbecility and an outrage” began to lose their religion. ... The international systems that chastened figures such as Keynes helped produce in the next few years – especially the Bretton Woods agreement and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (Gatt) – set the terms under which the new wave of globalization would take place. ... “Gatt’s purpose was never to maximize free trade,” Rodrik writes. “It was to achieve the maximum amount of trade compatible with different nations doing their own thing. In that respect, the institution proved spectacularly successful.” ... Partly because Gatt was not always dogmatic about free trade, it allowed most countries to figure out their own economic objectives, within a somewhat international ambit. ... If a nation wanted to protect its steel industry, for example, it could claim “injury” under the rules of Gatt and raise tariffs to discourage steel imports: “an abomination from the standpoint of free trade”. ... Gatt, however, failed to cover many of the countries in the developing world. These countries eventually created their own system, the United Nations conference on trade and development (UNCTAD). Under this rubric, many countries – especially in Latin America, the Middle East, Africa and Asia – adopted a policy of protecting homegrown industries by replacing imports with domestically produced goods. It worked poorly in some places – India and Argentina, for example, where the trade barriers were too high, resulting in factories that cost more to set up than the value of the goods they produced – but remarkably well in others, such as east Asia, much of Latin America and parts of sub-Saharan Africa, where homegrown industries did spring up.

The critical turning point – away from this system of trade balanced against national protections – came in the 1980s. Flagging growth and high inflation in the west, along with growing competition from Japan, opened the way for a political transformation. The elections of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan were seminal, putting free-market radicals in charge of two of the world’s five biggest economies and ushering in an era of “hyperglobalization”. In the new political climate, economies with large public sectors and strong governments within the global capitalist system were no longer seen as aids to the system’s functioning, but impediments to it.

Not only did these ideologies take hold in the US and the UK; they seized international institutions as well. Gatt renamed itself as the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the new rules the body negotiated began to cut more deeply into national policies. Its international trade rules sometimes undermined national legislation. ... If national health and safety regulations were stricter than WTO rules necessitated, they could only remain in place if they were shown to have “scientific justification”.

The purest version of hyperglobalization was tried out in Latin America in the 1980s. Known as the “Washington consensus”, this model usually involved loans from the IMF that were contingent on those countries lowering trade barriers and privatizing many of their nationally held industries. ... But the Washington consensus was bad for business: most countries did worse than before. Growth faltered, and citizens across Latin America revolted against attempted privatizations of water and gas.

It’s not only the discourse that’s changed: globalization itself has changed, developing into a more chaotic and unequal system than many economists predicted. The benefits of globalization have been largely concentrated in a handful of Asian countries. And even in those countries, the good times may be running out.

Rodrik, too, believes that globalization, whether reduced or increased, is unlikely to produce the kind of economic effects it once did. For him, this slowdown has something to do with what he calls “premature deindustrialisation”. In the past, the simplest model of globalization suggested that rich countries would gradually become “service economies”, while emerging economies picked up the industrial burden. Yet recent statistics show the world as a whole is deindustrializing. Countries that one would have expected to have more industrial potential are going through the stages of automation more quickly than previously developed countries did, and thereby failing to develop the broad industrial workforce seen as a key to shared prosperity.

Shifting away from the earlier emphasis on globalization had now become a political priority; to pursue still greater liberalization was like showing “a red rag to a bull” in terms of what it might do to the already compromised political stability of the western world.

Rodrik felt that economics commentary failed to register the gravity of the situation: that there were increasingly few avenues for global growth, and that much of the damage done by globalization – economic and political – is irreversible. “There is a sense that we’re at a turning point,” he said. “There’s a lot more thinking about what can be done. There’s a renewed emphasis on compensation – which, you know, I think has come rather late.”

*****

So in a nutshell, globalization has risen, grown more extreme, and now appears to be failing. Before we can get to "a lot more thinking about what can be done" to reach the proper levels of globalization, however, I think it's important to go beneath the history of the idea and understand it better technically by focusing on two things from the middle of the recap above:

- Economists had long embraced the principle of comparative advantage – simply put, the idea that countries will trade with each other in order to gain what each lacks, thereby benefiting both.

- No matter how troubling some of the local effects, the implication went, globalization promised a greater good.

Note that these statements are about benefits and the greater good — that means we're talking philosophy now using utilitarian terminology! But before we can philosophically examine the idea of the greater good, we first have to understand the economic theory that globalization rests upon: comparative advantage. Just how much benefit are we actually getting from it in theory?

2.

David Ricardo developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in 1817 to "explain why countries engage in international trade even when one country's workers are more efficient at producing every single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing two commodities engage in the free market, then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage. ... Widely regarded as one of the most powerful yet counter-intuitive insights in economics, Ricardo's theory implies that comparative advantage rather than absolute advantage is responsible for much of international trade."

To understand this clearly, I think it helps to see some numbers in an example. Ricardo famously used two fictitious nations known as "England" and "Portugal" who each produced cloth and wine according to the following formulas:

- England: 100 hours / yard of cloth, and 120 hours / bottle of wine

- Portugal: 90 hours / yard of cloth, and 80 hours / bottle of wine

Note that in this example Portugal is more efficient at producing both cloth and wine. Therefore, why would they ever trade with England? Well, the answer is because of comparative advantage. Portugal has to spend 90% as much time as England to produce cloth, but only 67% as much time to produce wine. Therefore, although they are absolutely better at producing both products, they are comparatively even more efficient at producing wine. Knowing this, economists say the two countries should specialize and trade with one another. This is because of the outcomes for the following options:

- England: in 220 hours could produce 1 cloth + 1 wine, or they could produce 2.2 cloth + 0 wine

- Portugal: in 170 hours could produce 1 cloth + 1 wine, or they could produce 0 cloth + 2.125 wine

See what happened there? By specializing, the total output of the two countries increased from 2 cloth & 2 wine to 2.2 cloth and 2.125 wine. As long as there is free trade, both countries are better off! This is literally the mathematical proof that is used to intellectually justify a religious belief in free trade that has given rise to extreme versions of globalization.

But are these countries really better off? What if it's nice to have a bit of English wine with some meals? What if the former Portuguese cloth makers are allergic to wine or can't all relocate to the Douro Valley? Free trade advocates say the market will work this all out in the long run, but as John Maynard Keynes said:

...this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task, if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past, the ocean is flat again.

The extremely simplified math of comparative advantage ignores many, many tempestuous problems. But even if those issues were all addressed by benevolent politicians, as long as they rely on the theory of comparative advantage to formulate policy advice, the result is enormous economies being turned into over-specialized entities with no room for diversity. As this occurs, it alienates larger and larger portions of society, as well as overdevelops core competencies until they become too big to fail. Until, that is, they catastrophically do. Sound familiar?

As Nassim Taleb noted in The Black Swan, this kind of naive optimization by the managerial class creates fragility; it creates one big monoculture bet on a crystalized design with no margin for error. Nature, on the other hand, relies on robustness to survive. Evolutionary history shows the importance of redundancy in things such as two lungs, two kidneys, multiple offspring, diversity within species, the overlapping of niche roles within ecosystems, and the importance of geographical isolation because it reduces the magnitude of calamity when trials inevitably result in errors. Taleb joked how grotesque a human would look if it were optimized by an MBA consultant, but now that services make up 80% of the UK economy, do we recognize such deformity in a country? Now that humans and our domesticated animals make up 98% of the world's vertebrates, do we recognize that deformity in ecosystems?

3.

How did we get here? Much of the theoretical development is traced in a recent Aeon article from professor John McCumber, titled: America’s hidden philosophy: When Cold War philosophy tied rational choice theory to scientific method, it embedded the free-market mindset in US society. Here are the vital passages:

As [the Cold War] was happening, US academics were faced with the task of coming up with a philosophical antidote to Marxism. Rational choice theory, originally developed at the RAND Corporation in the late 1940s, was a plausible candidate. It holds that people make (or should make) choices rationally by ranking the alternatives presented to them with regard to the mathematical properties of transitivity and completeness. They then choose the alternative that maximizes their utility, advancing their relevant goals at minimal cost. Each individual is solely responsible for her preferences and goals, so rational choice theory takes a strongly individualistic view of human life.

This Cold War philosophy also influences US society through its ethics. Its main ethical implication is somewhat hidden, because Cold War philosophy inherits from rational choice theory a proclamation of ethical neutrality: a person’s preferences and goals are not subjected to moral evaluation. As far as rational choice theory is concerned, it doesn’t matter if I want to end world hunger, pass the bar, or buy myself a nice private jet; I make my choices the same way.

It also has an ethical imperative that concerns not ends but means. However laudable or nefarious my goals might be, I will be better able to achieve them if I have two things: wealth and power. We therefore derive an ‘ethical’ imperative: whatever else you want to do, increase your wealth and power!

From Plato to the pragmatists, philosophical ethics has concerned the integration of the individual into a wider moral universe, whether divine (as in Platonic ethics) or social (as in the pragmatists). This is explicitly rejected by Cold War philosophy’s individualism and moral neutrality as regards to ends. Where Adam Smith had all sorts of arguments as to why greed was socially beneficial, Cold War ethics dispenses with them in favor of Gordon Gekko’s simple ‘Greed is good.’

These theoretical developments flowed right into the very first words that I, and thousands of others like me, heard in the Fall of 2000 when I entered my MBA program:

The purpose of a business is to make money.

This statement is true in practice because money is the only means of competition within an economy. The more of it you have, the more investment you can make in your business to improve it and win over customers from your competitors. This is the logic behind most decisions by business leaders — compete hard for money in the the short term because if you don't there won't be a long term. Some small private companies can eschew this and fly below the radar, almost like pilot fish swimming with the big sharks. But if those sharks turn on you (think Wall Mart on mom and pop), then there's not much hope. If you are a shark, and work in a publicly traded company, you cannot ignore this maxim because Wall Street will insist the purpose of your business is to make money, and it will punish your stock price (which is often tied to your own salary) if you disagree, because they will then view your company as not worth investing in.

Note that this statement about the profit-making purpose of business is legally true too for officers of corporations. They have fiduciary responsibilities and duties that require them to act "in the best interests of the company," which in essence means to maximize profit. There is some leeway for judgment of what is best for the business, but you cannot decide to ignore tax loopholes, or employ only in America, or act to "save the environment," because those actions are in the interests of others. Besides the drop in stock price, violations of fiduciary duty may lead to shareholder revolts or criminal prosecutions depending on how egregiously the fiduciary benefit was harmed. So no matter how many ethics classes get taught at business schools, any philosopher king CEO's will still have their hands tied by this competitive environment that they are in.

The problem, of course, is that while making money may be the purpose of business, it is not the purpose of life. Money is merely a theoretical concept used to ease the exchange of value. But there are (at least) two big problems with this concept.

- What do you do when people provide value to things that cannot repay them with money? Like babies or the environment?

- The laws of supply and demand break down when you try to determine prices for unique items. Such things are technically irreplaceable so their price, as calculated by supply and demand curves, runs to infinity.

Of course, no one pays mothers for their work, and prices for elephant hunts are not $∞. These underlying flaws with the concept of money are ignored, however, and it is simply left to work in the markets for widgets where it is easiest to understand. Governments create money, and they should be the legal entities that correct for these and other flaws. But as I've noted in the past, the most cited definition for the purpose of government comes from the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, which goes like this (with some numbering added for ease of analysis):

We the People of the United States, in Order to (1) form a more perfect Union, (2) establish Justice, (3) insure domestic Tranquility, (4) provide for the common defense, (5) promote the general Welfare, and (6) secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

The framers of the U.S. Constitution gave no guidance on how to prioritize among these six interests though, which often compete directly with one another. How do we choose between more liberty and more justice, other than by the democratic squabbling of the loudest groups or wealthiest interests? As explained above, this vacuum of ambiguity has been filled by the Cold War Philosophy and the Washington Consensus to now promote the liberty of individuals as the highest end goal. But that is entirely amoral. And since that which gets measured is the only thing that gets managed, and since money is easy to measure, governments overwhelmingly listen in this moral vacuum to business' interests in profits, and reports about the total size of the economy, despite the well known trouble with GDP that it fails as a measure of well-being.

In my view, a much better way to prioritize among the six interests in the Preamble would be according to the way we ought to prioritize all moral decision-making. We ought to act for the long-term survival of life in general. That's in line with the purpose of government that I described in Draining the Swamp, my novel of political philosophy. In that book, my heroine gave an election speech where she said:

Government is created to regulate the markets for all goods and services in order to ensure the fundamental evolutionary principles of cooperation and competition are acting for the maximum benefit of all life.

In other words, the highest pursuit of government should not be the amoral freedom of the individual to pursue whatever they want, with money as the only measure of their success. The fact that such a pursuit is amoral doesn't mean that it is always immoral. Greed and self-interest, acting as invisible hands, can be good. But only if they are balanced against considerations for the competing needs of all forms of life. What are those needs? I've said many times on here that I think an evolutionary philosophy points towards the survival of life over the long term as the ultimate objective goal for all the actions of life. But I think it's time for me to fill in some more details on guidance for how we get there.

4.

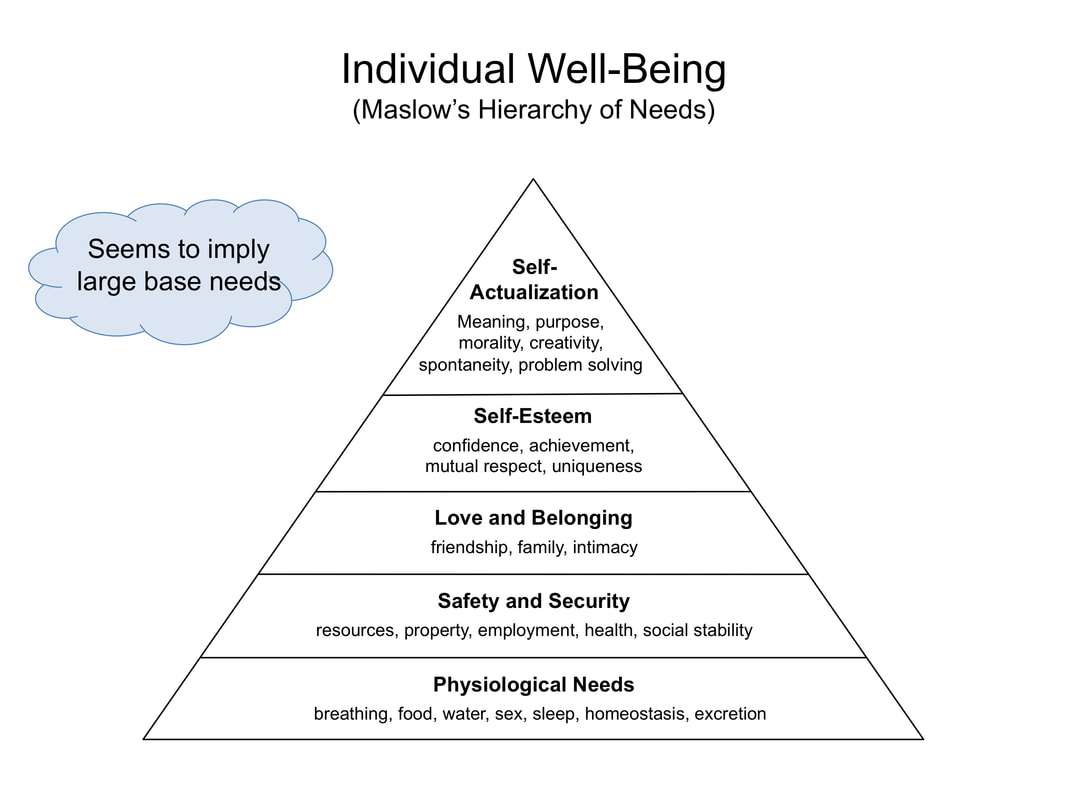

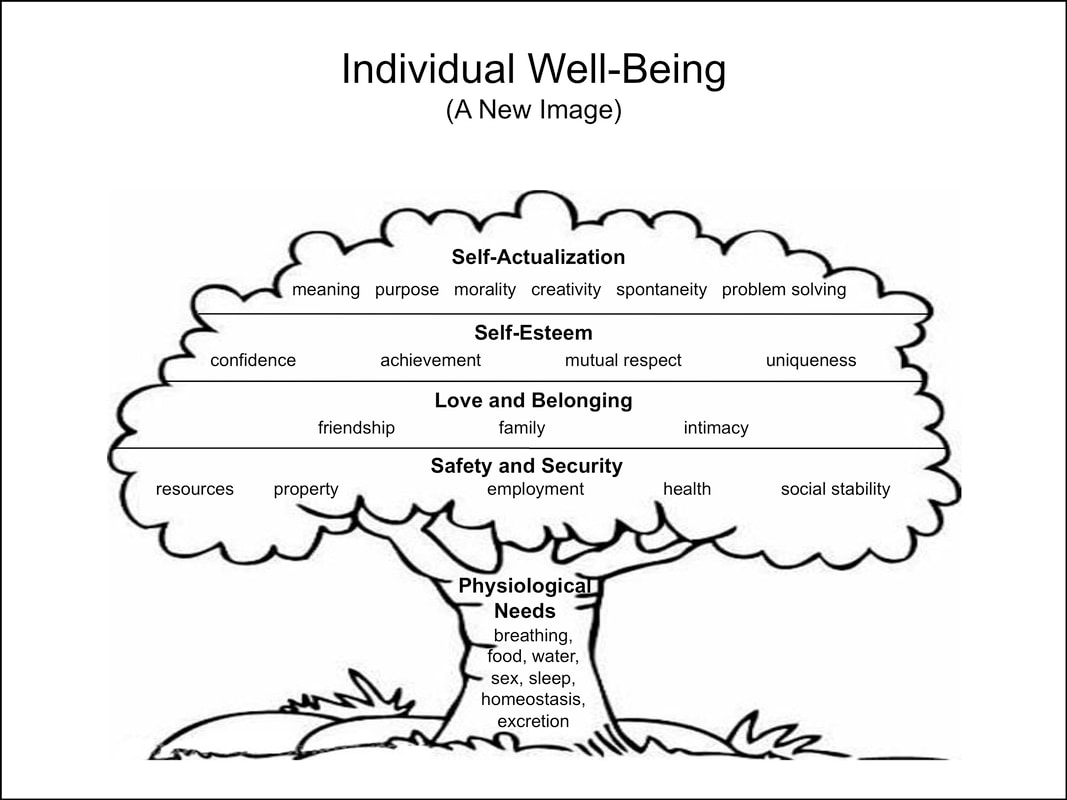

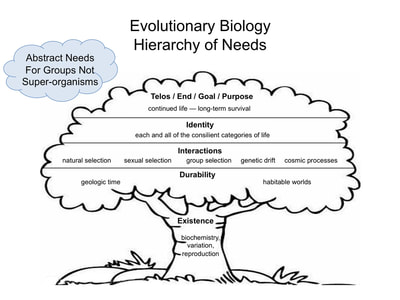

The first place to start sketching the needs of life in general is with the needs of the individual. That has been the focus with perhaps the most research behind it, so it will give us an excellent framework to proceed. To date, the best representation of this research has been in Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

- Physiological Needs → Existence

- Safety and Security → Durability

- Love and Belonging → Interactions

- Self-Esteem → Identity

- Self-Actualization → Telos

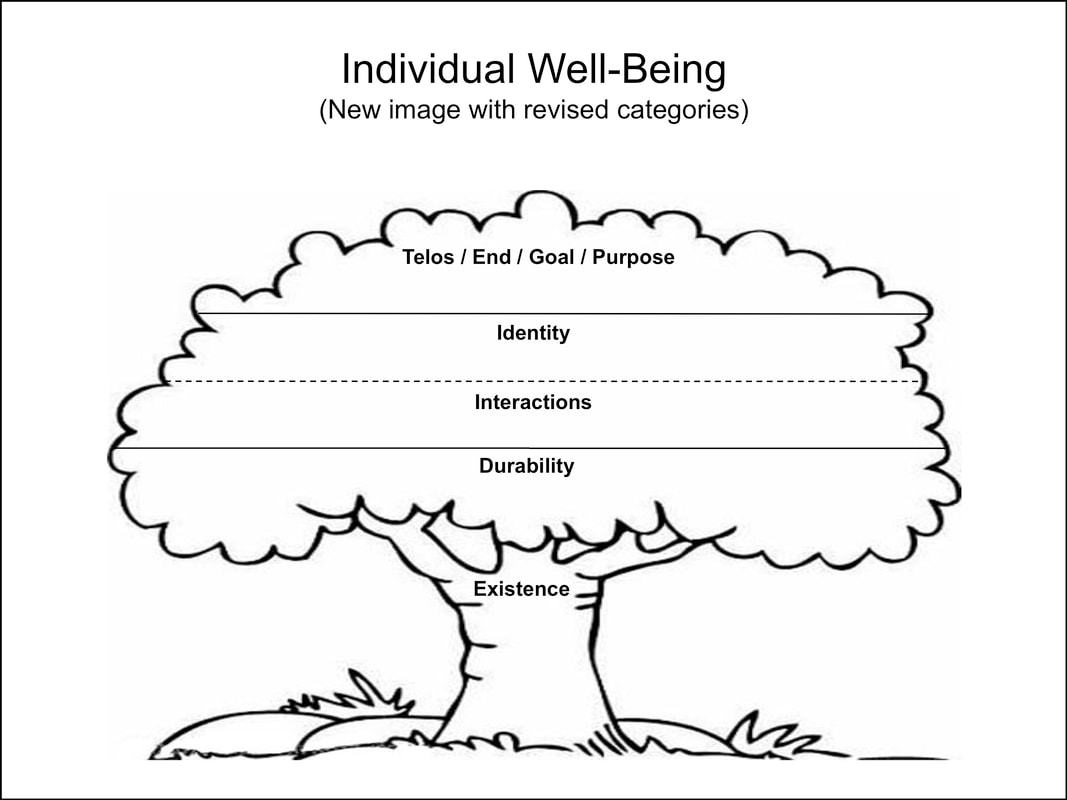

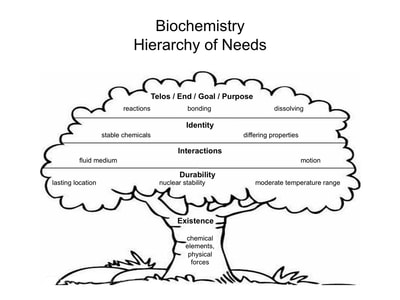

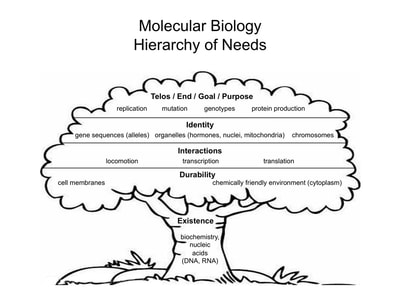

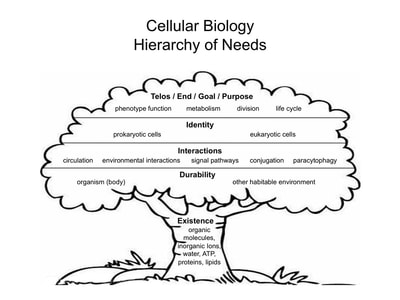

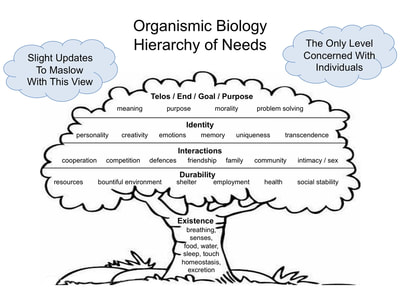

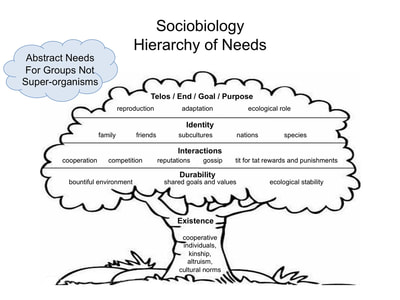

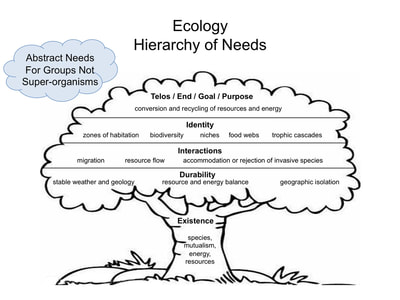

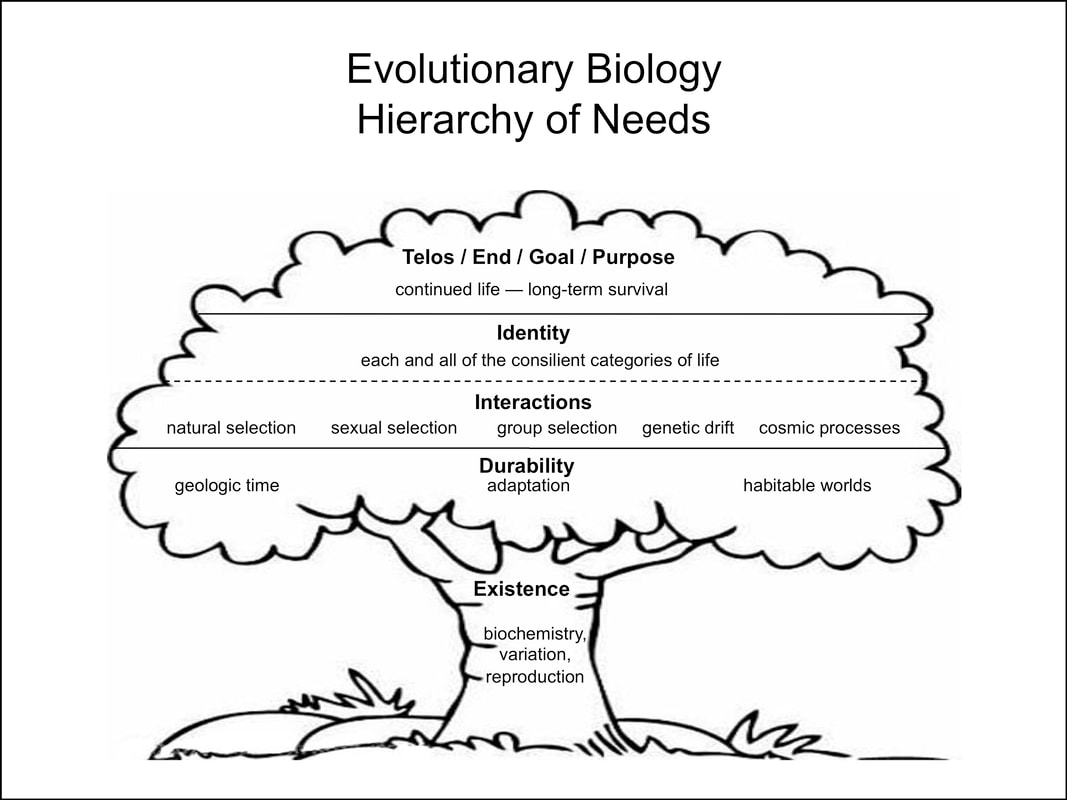

I haven't read Maslow in depth to know how he derived the five levels of his hierarchy, but I believe they map almost perfectly to these new categories that fit the brute details of all life in a changing and multitudinous universe. First, life needs basic ingredients just to exist. Next, it needs the right conditions to survive over time. The third and fourth levels influence each other in an unavoidably bi-directional fashion. All living things need to interact with other living things and are thus defined into an identity. You could flip levels 3 and 4, and I wouldn't protest, but I'll stick with this order to hew closer to Maslow. This would also make existentialists happy since the existence of interactions with the environment precedes the identity of an essence. Finally, living things must realise their end, goal, or purpose in order to (consciously or unconsciously) act. Aristotle popularised the use of the Greek word telos to describe this idea in philosophy, and I think it fits well here. Now we are ready to extend this model for well-being from individuals to others. But to whom exactly?

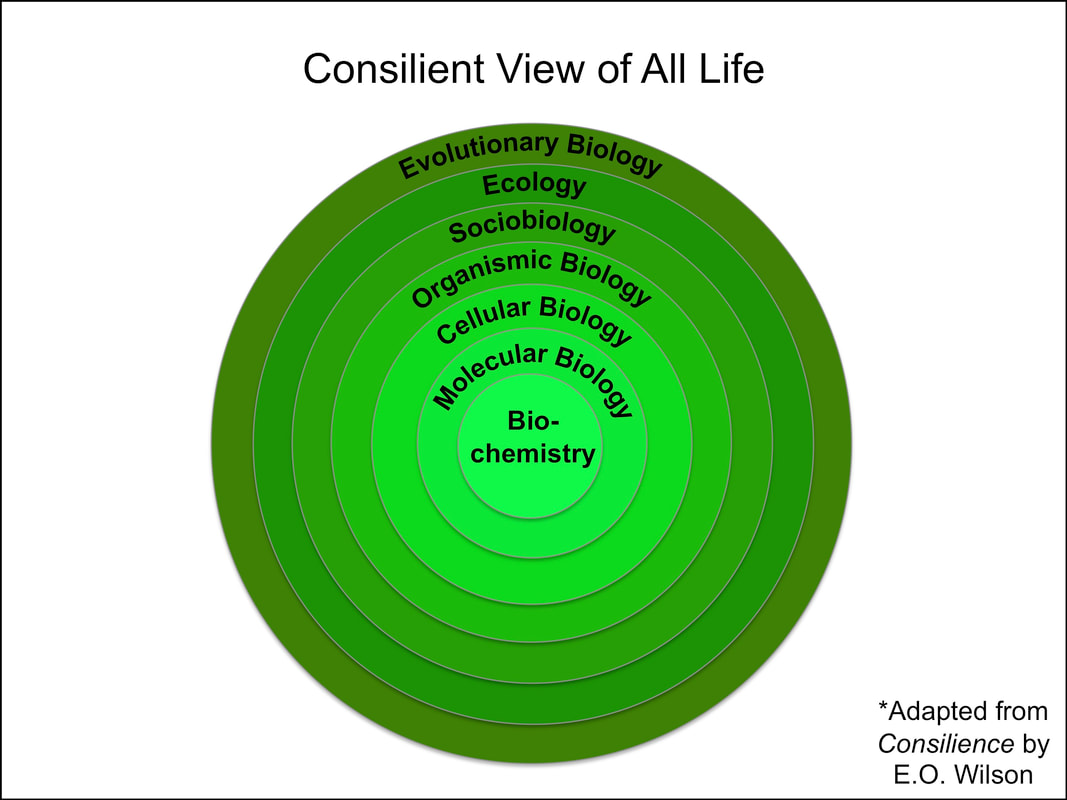

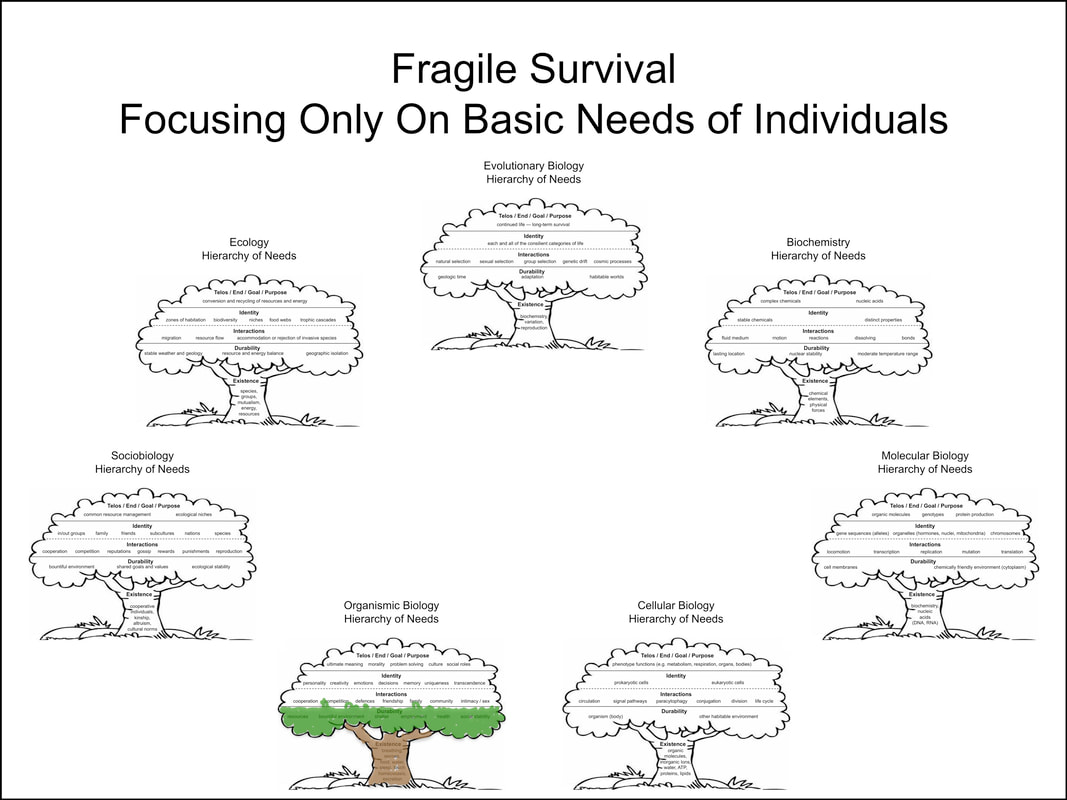

1) Biochemistry → 2) Molecular Biology → 3) Cellular Biology → 4) Organismic Biology → 5) Sociobiology → 6) Ecology → 7) Evolutionary Biology

These seven categories describe the study of life in totality. Therefore, if you want "to act for the maximum benefit of all life," which is what I said is the purpose of government, then you need to consider what is needed for life to survive and thrive in each of these areas. I won't take the time to go through the details for all of this in this post, but you can step through them one at a time by clicking on the pictures below.

We began this thought experiment with a question about how to solve an economic problem that has arisen via naive globalisation. At the end of section 1, we saw economists admit that “there’s still a lot more thinking about what can be done" for this issue. Now, after a very long post, after several years of blogging about evolutionary philosophy, and at the end of this book of thought experiments, I hope I've shown how to consider problems like this in the widest possible context in order to set our priorities correctly and act accordingly. Tradeoffs such as the fair trade scheme are perhaps the best examples of what may be required for more sustainable levels of international interactions. If that means slower economic growth, so be it. Clearly the fastest economic growth is blowing up in our face, and it does not meet the wider needs of life on Earth. At this point, we've come too far to painlessly change to a new kind of globalization based on something like "evonomics," or an "Ecotopia," but someone will have to bear the pain of our faults sometime. I say we need to have the personal courage to tell our politicians to run governments that bring that pain now, to those who can bear it best, in as minimal a fashion as possible, but in order to wisely redesign our societies for a robustly enduring future. As I suggest at the top of every page on this website, we can contemplate the past and choose the destination. So thank you for coming there along with me....wherever it is that we all end up.