So, which one should we tackle first? I believe we have to start by trying to nail down the functions of consciousness. Without that, how would we even know what to look for in terms of mechanisms, ontogeny, and phylogeny? This is a big task though. Remember that Tinbergen carved out the biological view of function in his 2x2 matrix as static (the current form of an organism) and ultimate (why a species evolved the structures that it has). This “static + ultimate” view of a function means that we are looking for a species trait that solves a reproductive or survival problem in the current environment. The problem with trying to do this for “consciousness” is that it is such a multi-faceted complex concept, there are therefore many, many aspects of consciousness that solve many, many reproductive and survival problems. And if we are trying to do so for a general definition of consciousness that applies across all organisms, then we have an even bigger set of possibilities that needs to encompass all of the evolutionary history of life. It’s a good thing we already covered a brief history of everything that has ever existed!

Since a review of the functions of consciousness can quickly get unwieldy, I’m going to write it in a way that helps us (i.e. me) hold onto the thread of the plot. I’m going to write a series of numbered statements (42 in all) with the justification for each one coming after the statement. You can just quickly read the statements to get the gist of the argument if you like. Or you can dip into the rest of the ~10,000 words to find any details you might want. Hopefully that will work well for a variety of readers with lots of differing backgrounds. Let’s begin.

1. Naming an evolved function for consciousness has proven to be very difficult and there is no widely accepted position on this.

- If consciousness exists as a complex feature of biological systems, then its adaptive value is likely relevant to explaining its evolutionary origin, though of course its present function, if it has one, need not be the same now as when it first arose. (Consciousness Entry in Stanford Encyclopedia)

- Why did evolution result in creatures who were more than just informationally sensitive? [Instead, they are ‘experientially sensitive’ too.] There are, to the best of our knowledge, no good theories about this. … Surely we jest, the reader might think. There must be good theories for why consciousness evolved. Well we have looked far and wide and no credible theories emerge. … There are as yet no credible stories about why subjects of experience emerged, why they might have won—or should have been expected to win—an evolutionary battle against very intelligent zombie-like information sensitive organisms. At least this has not been done in a way that provides a respectable theory for why subjects of experience gained hold in this actual world—for why we are not zombies. (Flanagan and Polger)

2. A common way to express this difficulty is to ask what life would be like without consciousness? Would life as a “zombie” look any different?

- Zombie thought experiments highlight the need to explain why consciousness evolved and what function(s) it serves. This is the hardest problem in consciousness studies. … If systems “just like us” could exist without consciousness, then why was this ingredient added? Does consciousness do something that couldn’t be done without it? (Flanagan and Polger)

- Why doesn't all this information-processing go on “in the dark,” free of any inner feel? Chalmers (1995) insists that consciousness cannot be explained in functional terms. He claims that reducing consciousness (as we experience it) to a functional mechanism will never solve the hard problem. (Solms)

3. “Zimboes” show the preposterousness of these zombie claims.

- Todd Moody [notes that] although “it is true that zombies who grew up in our midst might become glib in the use of our language, including our philosophical talk about consciousness [and other mentalistic concepts], a world of zombies could not originate these exact concepts.” … Zombies, lacking the inner life that is the referent for our mentalistic terms, will not have concepts such as ‘dreaming’, ‘being in pain’, or ‘seeing’. This, Moody says, will reveal itself in the languages spoken on Zombie Earth, where terms for conscious phenomena will never be invented. The inhabitants of Zombie Earth won’t use the relevant mentalistic terms and thus will show “the mark of zombiehood”. (Flanagan and Polger)

- Todd Moody's (1994) essay on zombies, and Owen Flanagan and Thomas Polger's commentary on it, vividly illustrate a point I have made before, but now want to drive home: when philosophers claim that zombies are conceivable, they invariably under-estimate the task of conception (or imagination), and end up imagining something that violates their own definition. … Only zimboes could pass a demanding Turing Test, for instance. … Zimboes think they are conscious, think they have qualia, think they suffer pains—they are just ‘wrong' (according to this lamentable tradition), in ways that neither they nor we could ever discover! … Zimboes are so complex in their internal cognitive architecture that whenever there is a strong signal in either the pain or the lust circuitry, all these 'merely informational' effects, (and the effects of those effects, etc.) are engendered. That's why zimboes, too, wonder why sex is so sexy for them [but not for simpler zombies, such as insects] and why their pains have to 'hurt'. If you deny that zimboes would wonder such wonders, you contradict the definition of a zombie. … Zombies would pull their hands off hot stoves, and breed like luna moths, but they wouldn't be upset by memories or anticipations of pain, and they wouldn't be apt to engage in sexual fantasies. No. While all this might be true of simple zombies, zimboes would be exactly as engrossed by sexual fantasies as we are, and exactly as unwilling to engage in behaviours they anticipate to be painful. If you imagine them otherwise, you have just not imagined zombies correctly. (Dennett)

4. So, what is the purpose of consciousness? That’s a poorly formed question because there is no one thing that consciousness is, so there is no one purpose that it is for.

- The question of adaptive advantage, however, is ill-posed in the first place. If consciousness is (as I argue) not a single wonderful separable thing ('experiential sensitivity') but a huge complex of many different informational capacities that individually arise for a wide variety of reasons, there is no reason to suppose that 'it' is something that stands in need of its own separable status as fitness-enhancing. It is not a separate organ or a separate medium or a separate talent. To see the fallacy, consider the parallel question about what the adaptive advantage of health is. (Dennett)

- I am not suggesting that there are not numerous empirical problems about the various forms of consciousness. We should like to understand, not what consciousness is for, but rather what sleep is for. It is of interest to know the neural mechanisms involved in perceptual consciousness (i.e. of having one’s attention caught by something in one’s field of perception). It is important to discover how the brain maintains intransitive consciousness. And so on. My point is merely that the so-called ‘hard problem’ of consciousness, and the battery of related questions often cited by philosophers are merely conceptual confusions masquerading as empirical questions. (Hacker)

5. We must drop the essentialist language of consciousness. Consciousness isn’t a thing that just turns on. It involves the slow accrual of many properties. I defined it around detecting and responding to biological forces.

- I think a more natural joint to carve a philosophical place for consciousness is in the biological realm where life responds to biological forces in order to survive. (Post 17)

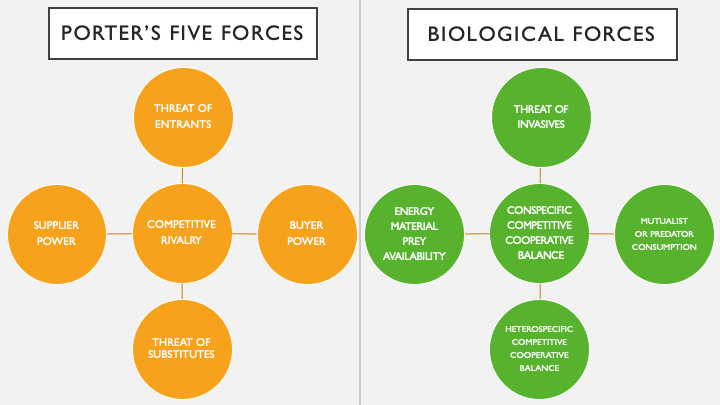

- In the field of strategic management. Harvard business school professor Michael Porter noted that you could map the competitive environment of any industry in order to understand the industry’s attractiveness in terms of profitability. Porter’s five forces are exerted by: 1) suppliers (supplier power), 2) buyers (buyer power), 3) entrants (threat of new entrants), 4) substitutes (threat of substitution), and 5) competitors (competitive rivalry). (Post 17)

- In biology, there is 1) consumption of upstream inputs of energy, material, or prey (suppliers); 2) consumption of downstream outputs by mutualists, micro- or macroscopic predators (buyers); 3) potentially invasive species (threat of entrants); 4) current niche competitors from heterospecifics in other species (substitutes); and 5) the balance between competition and cooperation among conspecifics from the same species (competitive rivalry). (Post 17)

6. Defining consciousness this way implies that the processes of consciousness began with the origins of life. Our current best guess for how that occurred involves chemical and physical processes leading to simple constructions that were separable, stable, and replicable.

- The pre-biotic environment contained many simple fatty acids. Under a range of pH, they spontaneously form stable vesicles (fluid-filled bladders). When a vesicle encounters free fatty acids in solution, it will incorporate them. Eating and growth are driven purely by thermodynamics. … The pre-biotic environment contained hundreds of types of different nucleotides (not just DNA and RNA). All it took was for one to self-polymerize. … No special sequences are required. It’s just chemistry. … So far, we have lipid vesicles that can grow and divide, and nucleotide polymers that can self-replicate, all on their own. But how does it become life? Here’s how. Our fatty acid vesicles are permeable to nucleotide monomers, but not polymers. (Single chains can get in; bonded ones can’t get out.) Once spontaneous polymerization occurs within the vesicle, the polymer is trapped. Floating though the ocean, the polymer-containing vesicles will encounter convection currents such as those set up by hydrothermal vents. The high temperatures will separate the polymer strands and increase the membrane’s permeability to monomers. Once the temperature cools, spontaneous polymerization can occur. And the cycle repeats. Here’s where it gets cool. The polymer, due to surrounding ions, will increase the osmotic pressure within the vesicle, stretching its membrane. A vesicle with more polymer, through simple thermodynamics, will “steal” lipids from a vesicle with less polymer. This is the origin of competition. They eat each other. A vesicle that contains a polymer that can replicate faster will grow and divide faster, eventually dominating the population. Thus beginning evolution! (Post 17)

7. These earliest structures satisfy at least 3 of the 7 major traits that currently define life: organization, growth, and reproduction.

- The definition of life has long been a challenge for scientists and philosophers, with many varied definitions put forward. This is partially because life is a process, not a substance. Most current definitions in biology are descriptive. Life is considered a characteristic of something that preserves, furthers, or reinforces its existence in the given environment. According to this view, life exhibits all or most of the following traits:

- Homeostasis: regulation of the internal environment to maintain a constant state; for example, sweating to reduce temperature.

- Organization: being structurally composed of one or more cells—the basic units of life.

- Metabolism: transformation of energy by converting chemicals and energy into cellular components (anabolism) and decomposing organic matter (catabolism). Living things require energy to maintain internal organization (homeostasis) and to produce the other phenomena associated with life.

- Growth: maintenance of a higher rate of anabolism than catabolism. A growing organism increases in size in all of its parts, rather than simply accumulating matter.

- Adaptation: the ability to change over time in response to the environment. This ability is fundamental to the process of evolution and is determined by the organism's heredity, diet, and external factors.

- Response to stimuli: a response can take many forms, from the contraction of a unicellular organism to external chemicals, to complex reactions involving all the senses of multicellular organisms. A response is often expressed by motion; for example, phototropism (the leaves of a plant turning toward the sun), and chemotaxis (movement of a motile cell or organism, or part of one, in a direction corresponding to a gradient of increasing or decreasing concentration of a particular substance).

- Reproduction: the ability to produce new individual organisms, either asexually from a single parent organism or sexually from two parent organisms. (Post 17)

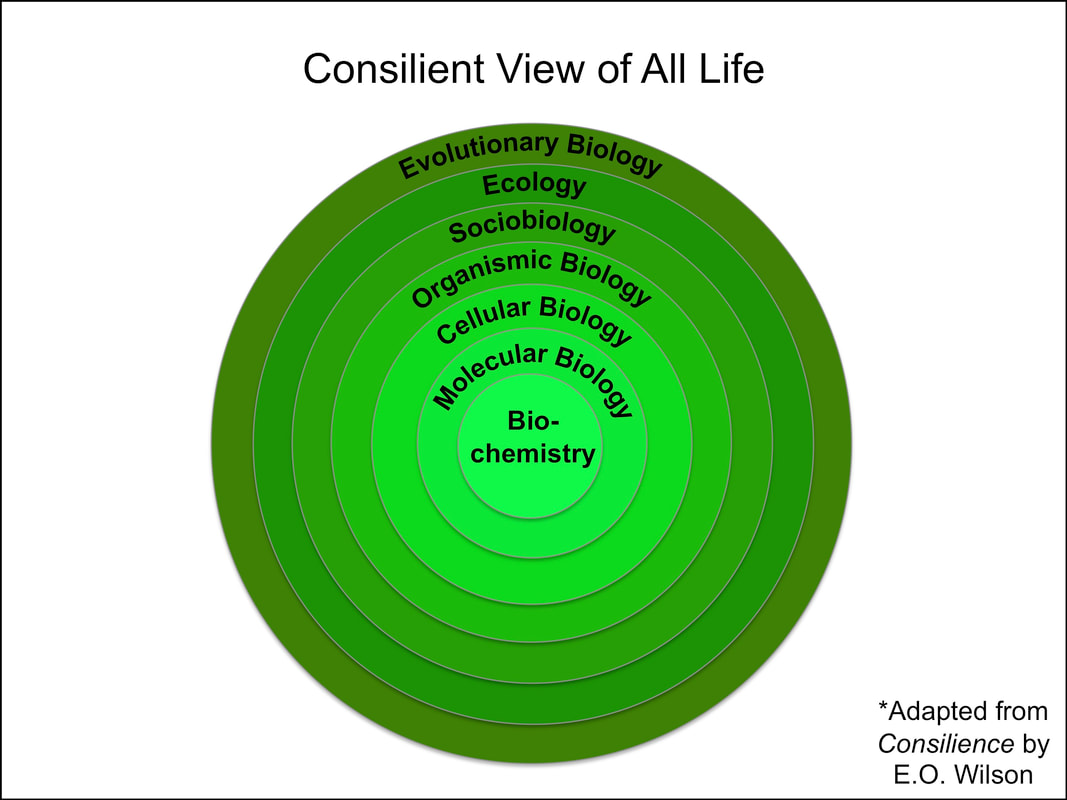

8. Within E.O. Wilson’s consilient view of all of life, this gets us from biochemistry to molecular biology.

- In his book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, E.O. Wilson proposed seven categories to integrate all of the biological sciences. His seven categories describe the study of life in totality, from the smallest atomic building blocks, to the billions of years of life-history that they have all constructed. Therefore, the simple diagram below of these mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive categories is actually an astonishingly broad vision of all of the life that has ever existed or will ever exist. (Post 17)

9. Any changes to these biological molecules would generate forces. These forces are exerted on singularly identifiable objects.

- Molecules are held together by covalent bonds, which involve the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. Covalent bonding occurs when these electron pairs form a stable balance between attractive and repulsive forces between atoms. Covalent bonding does not necessarily require that the two atoms be of the same elements, only that they be of comparable electronegativity. … Intermolecular forces are the forces which mediate interactions between molecules and other types of neighboring particles such as atoms or ions. They are weak relative to the intramolecular forces of covalent bonding which hold a molecule together. … Intermolecular forces are electrostatic in nature; that is, they arise from the interaction between positively and negatively charged molecules. The four key intermolecular forces are: 1) Ionic bonds; 2) Hydrogen bonding; 3) Van der Waals dipole-dipole interactions; and 4) Van der Waals dispersion forces. (Post 17)

10. I propose that these chemical forces, once in service of biological needs, are the defined starting point for turning objects into subjects.

- Foundational to what we call psychology is the subjective observational perspective. The fact that self-organizing systems must monitor their own internal states in order to persist (that is, to exist, to survive) is precisely what brings active forms of subjectivity about. The very notion of selfhood is justified by this existential imperative. It is the origin and purpose of mind. (Solms)

11. As these living subjects evolve to survive and reproduce in accordance with the laws of natural and (later) sexual selection, any changes that occur in their makeup will induce chemical forces. Those that lead towards better survival and reproductive chances are objectively good for the subject and take on the affective valence of pleasure. The opposite is objectively bad and painful. Homeostasis is a comfortable stable state in between. These states of affective valence are fundamental components of consciousness.

- Consciousness is fundamentally affective (see Panksepp, 1998; Solms, 2013; Damasio, 2018). The arousal processes that produce what is conventionally called “wakefulness” constitute the experiencing subject. In other words, the experiencing subject is constituted by affect. (Solms)

- We have seen that minds emerge in consequence of the existential imperative of self-organizing systems to monitor their own internal states in relation to potentially annihilatory, entropic forces. Such monitoring is an inherently value-laden process. It is predicated upon the biological ethic (which underwrites the whole of evolution) to the effect that survival is “good.” (Solms)

- Valence / value evolved much earlier. Even bacteria can go toward food and away from danger. (Post 10)

- The brainstem structures that generate conscious “state” are not only responsible for the degree but also for the core quality of subjective being. The primal conscious “state” of mammals is intrinsically affective. It is this realization that will revolutionize consciousness studies in future years. (Solms and Panksepp)

- Homeostasis is the primary mechanism driving life. Emotions are chemical reactions. The emotive response triggered by sensory stimuli are the qualia of philosophical tradition. This subjectivity is the critical enabler of consciousness. (Post 10)

- Affective qualia are accordingly claimed to work like this: deviation away from a homeostatic settling point (increasing uncertainty) is felt as unpleasure, and returning toward it (decreasing uncertainty) is felt as pleasure. There are many types (or “flavors”) of pleasure and unpleasure in the brain (Panksepp, 1998). (Solms)

- Interoceptive consciousness is phenomenal; it “feels like” something. Above all, the phenomenal states of the body-as-subject are experienced affectively. Affects, rather than representing discrete external events, are experienced as positively and negatively valenced states. Their valence is determined by how changing internal conditions relate to the probability of survival and reproductive success. The empirical evidence for the feeling component are simply based on the highly replicable fact that wherever in the brain one can artificially evoke coherent emotional response patterns with deep brain stimulation, those shifting states uniformly are accompanied by “rewarding” and “punishing” states of mind. By attributing valence to experience—determining whether something is “good” or “bad” for the subject, within a biological system of values—affective consciousness (and the behaviors it gives rise to) intrinsically promotes survival and reproductive success. This is what consciousness is for. (Solms and Panksepp)

- The dumb id, in short, knows more than it can admit. Small wonder, therefore, that it is so regularly overlooked in contemporary cognitive science. But the id, unlike the ego, is only dumb in the glossopharyngeal sense. It constitutes the primary stuff from which minds are made; and cognitive science ignores it at its peril. We may safely say, without fear of contradiction, that were it not for the constant presence of affective feeling, conscious perceiving and thinking would either not exist or would gradually decay. This is just as well, because a mind unmotivated (and unguided) by feelings would be a hapless zombie, incapable of managing the basic tasks of life. (Solms and Panksepp)

- An explanation of experience will never be found in the function of vision—or memory, for that matter—or in any function that is not inherently experiential. The function of experience cannot be inferred from perception and memory, but it can be inferred from feeling. There is not necessarily “something it is like” to perceive and to learn, but who ever heard of an unconscious feeling—a feeling that you cannot feel? If we want to identify a mechanism that explains the phenomena of consciousness (in both its psychological and physiological aspects) we must focus on the function of feeling—the technical term for which is “affect.” (Solms)

12. Affective valence can only be felt by the subject experiencing the physical and chemical changes. There is, therefore, a barrier to knowing “what it is like” to be another subject. However, affect will eventually lead to distinctive behavior in complex animals that can be objectively observed.

- Behavioral criteria showing an animal has affective consciousness (likes and dislikes):

- Global operant conditioning (involving whole body and learning brand-new behaviors)

- Behavioral trade-offs, value-based cost-benefit decisions

- Frustration behavior

- Self-delivery of pain relievers or rewards

- Approach to reinforcing drugs or conditioned place preference (Feinberg and Mallatt)

13. These affects become separable into three categories and seven basic emotions.

- Subcortical affective processes come in at least three major categorical forms: (a) the homeostatic internal bodily drives (such as hunger and thermoregulation); (b) the sensory affects, which help regulate those drives (such as the affective aspects of taste and feelings of coldness and warmth); and (c) the instinctual-emotional networks of the brain, which embody the action tools that ambulant organisms need to satisfy their affective drives in the outside world (such as searching for food and warmth). These instinctual “survival tools” include foraging for resources (SEEKING), reproductive eroticism (LUST), protection of the body (FEAR and RAGE), maternal devotion (CARE), separation distress (PANIC/GRIEF), and vigorous positive engagement with conspecifics (PLAY). (Solms and Panksepp)

14. Cognition is built alongside and on top of this affective valence to sense, remember, and know more and more about what is bad and good. This happens in an ever-evolving way, growing in time, space, and circles of concern.

- “Cognition is comprised of sensory and other information-processing mechanisms an organism has for becoming familiar with, valuing, and interacting productively with features of its environment in order to meet existential needs, the most basic of which are survival/persistence, growth/thriving, and reproduction.” This specifies the adaptive value of cognition for an organism and has the additional virtue of differentiating cognition from metabolic functions such as respiration and photosynthesis, which arguably also employ mechanisms for acquiring, processing, and acting on information. … This proposed definition is consistent with Peter Sterling and Simon Laughlin’s (2015) description in Principles of Neural Design of what brains do, including the human brain: “The brain’s purposes reduce to regulating the internal milieu and helping the organism to survive and reproduce. All complex behavior and mental experience—work and play, music and art, politics and prayer—are but strategies to accomplish these functions.” (p. 11) (Lyon)

- What, then, does cortex contribute to consciousness? Although neocortex surely adds much to refined perceptual awareness, initial perceptual processing appears to be unconscious in itself (cf. blindsight) or it may have qualities that we do not readily recognize at the level of cognitive consciousness. … It is possible that perceptual and higher cognitive forms of consciousness emerged in the neocortex upon an evolutionary foundation of affective consciousness. (Solms and Panksepp)

15. Cognitive processing enables the interruption of affective reflexes in order to consider several things at once. Cognition thus gives stability to the fleeting nature of affective emotion. This stability allows for driven, intentional acts.

- It is argued here that cortex stabilizes consciousness rather than generates it; i.e., that cortical functioning binds affective arousal, and thereby transforms it into conscious cognition. … The essential task of cognitive (cortical) consciousness is to delay motor responses to affective “demands made upon the mind for work.” This delay enables thinking. The essential function of cortex is thus revealed to be stabilization of non-declarative executive processes, which is the essence of what we call working memory. (Solms)

- The fundamental contribution of cortex to consciousness in this respect is stabilization (and refinement) of the objects of perception and generating thinking and ideas. This contribution derives from the unrivalled capacity of cortex for representational forms of memory (in all of its varieties, both short- and long-term). To put it metaphorically, cortex transforms the fleeting, fugitive, wave-like states of consciousness into mental solids. It generates objects. (Freud called them “object presentations”.) Such stable representations, once established, can be innervated both externally and internally, thereby generating objects not only for perception but also for cognition. To be clear: the computations and memories underlying these representational processes are unconscious in themselves; but when consciousness is extended to them, it (consciousness) is transformed by them into something stable, something that can be thought, something in the nature of crystal clear perceptions that are transformed into ideas in working memory. (Solms and Panksepp)

16. Further cognition allows brains to become better reality simulators or prediction machines, which aid tremendously in prospects for survival.

- The evolutionary and developmental pressure to constrain incentive salience in perception through prediction-error coding (the “reality principle”) places inhibitory constraints on action. The resultant inhibition requires tolerance of frustrated affects, but it secures more efficient drive satisfaction in the long run. (Solms and Panksepp)

- In this process, the organism must stay “ahead of the wave” of the biological consequences of its choices (to use the analogy that gave Andy Clark's (2016) book its wonderful title: Surfing Uncertainty): “To deal rapidly and fluently with an uncertain and noisy world, brains like ours have become masters of prediction—surfing the waves of noisy and ambiguous sensory stimulation by, in effect, trying to stay just ahead of the place where the wave is breaking (p. xiv).” (Solms)

- What I am claiming is something else: feeling enables complex organisms to register—and thereby to regulate and prioritize through thinking and voluntary action—deviations from homeostatic settling points in unpredicted contexts. This adaptation, in turn, underwrites learning from experience. In predictable situations, organisms may rely on automatized reflexive responses (in which case, the biologically viable predictions are made through natural selection and embodied in the phenotype; see Clark, 2016). But if the organism is going to make plausible choices in novel contexts (cf. “free will”) it must do so via some type of here-and-now assessment of the relative value attaching to the alternatives (see Solms, 2014). (Solms)

17. The development and feelings of “precision” are an important part of how these predictions work.

- “Precision” is an extremely important aspect of active and perceptual inference; it is the representation of uncertainty. The precision attaching to a quantity estimates its reliability, or inverse variance (e.g., visual—relative to auditory—signals are afforded greater precision during daylight vs. night-time). Heuristically, precision can be regarded as the confidence afforded probabilistic beliefs about states of the not-system—or, more importantly, what actions “I should select.” (Solms)

- The feeling of knowing (“I do know that”) is a basic emotion like fear that is not under conscious control. (Campbell)

18. As cognitive predictions are tested, they take on valence where surprises and uncertainty are bad and therefore honed by evolution to improve. This cognitive valence is what philosophers seemingly refer to as qualia.

- Friston’s model of the Bayesian brain (in terms of which prediction-error or “surprise”, equated with “free energy”) is minimized through the encoding of better models of the world leading to better predictions is therefore, in principle, entirely consistent with the model outlined here. It is important to note that in this model, prediction error (mediated by the sensory affect of surprise), which increases incentive salience (and therefore conscious “presence” of the self) in perception, is a “bad” thing, biologically speaking. The more veridical the brain’s generative model of the world, the less surprise (the less salience, the less consciousness, the more automaticity), the better. Freud called this the “Nirvana principle”. [In simpler terms,] the goal of all learning is automatized mental processes, increased predictability, and reduced uncertainty or “surprise”. (Solms and Panksepp)

- The inherently subjective and qualitative nature of this auto-assessment process explains “how and why” it feels like something to the organism, for the organism (cf. Nagel, 1974). Specifically, increasing uncertainty in relation to any biological imperative just is “bad” from the (first-person) perspective of such an organism—indeed it is an existential crisis—while decreasing uncertainty just is “good.” (Solms)

- The proposal on offer here is that this imperative predictive function—which bestows the adaptive advantage of enabling organisms to survive in novel environments—is performed by feeling. On the present proposal, this is the causal contribution of qualia. (Solms)

19. Predictions about the intentions of others are particularly vital.

- I claim that our power to interpret the actions of others depends on our power—seldom explicitly exercised—to predict them. Where utter patternlessness or randomness prevails, nothing is predictable. The success of folk-psychological prediction, like the success of any prediction, depends on there being some order or pattern in the world to exploit. … Folk psychology provides a description system that permits highly reliable prediction of human (and much nonhuman) behavior. (Dennett)

- Understanding of others' intentions is a critical precursor to understanding other minds because intentionality, or “aboutness”, is a fundamental feature of mental states and events. The “intentional stance” has been defined by Daniel Dennett as an understanding that others' actions are goal-directed and arise from particular beliefs or desires. (Theory of Mind Wikipedia)

- Here is how it works: first you decide to treat the object whose behavior is to be predicted as a rational agent; then you figure out what beliefs that agent ought to have, given its place in the world and its purpose. Then you figure out what desires it ought to have, on the same considerations, and finally you predict that this rational agent will act to further its goals in the light of its beliefs. A little practical reasoning from the chosen set of beliefs and desires will in most instances yield a decision about what the agent ought to do; that is what you predict the agent will do. (p.17) (Dennett)

20. By making cognitive connections between intentions, predictions, and internal affective feelings, the development of self-awareness slowly arises.

- [At first,] the external body is not a subject but an object, and it is perceived in the same register as other objects. Something has to be added to simple perception before one’s own body is differentiated from others. This level of representation (a.k.a. higher-order thought) enables the subject of consciousness to separate itself as an object from other objects. We envisage the process involving three levels of experience: (a) the subjective or phenomenal level of the anoetic self as affect, a.k.a. first-person perspective; (b) the perceptual or representational level of the noetic self as an object, no different from other objects, a.k.a. second-person perspective; (c) the conceptual or re-representational level of the autonoetic self in relation to other objects, i.e., perceived from an external perspective, a.k.a. third-person perspective. The self of everyday cognition is therefore largely an abstraction. That is why the self is so effortlessly able to think about itself in relation to objects, in such everyday situations as “I am currently experiencing myself looking at an object”. (Solms and Panksepp)

21. Models of others and the self are made using the same mechanisms.

- In The Ancient Origins of Consciousness, Feinberg and Mallatt contend that consciousness is about creating image maps of the environment and oneself. But systems that do it with orders of magnitude less sophistication than humans can still trigger our intuition of a fellow conscious being. (Post 11)

- External body representation is made of the same “stuff” as the representation of other objects. The external bodily “self” is represented as a thing—“my body”—and is inscribed on the page of consciousness in much the same way as other objects. It is, in short, an external, stabilized, detailed representation of the subject of consciousness. It is not the subject itself. The subject of consciousness identifies itself with this external bodily representation in much the same way as a child might project itself into the animated figures that she controls in a computer game. The representations rapidly come to be treated as if they were the self, but in reality they are not. Here is some experimental evidence for the counterintuitive relation between the self and its external body. Petkova and Ehrsson reported a series of “body swap” experiments in which cameras mounted over the eyes of other people or mannequins, transmitting images from their viewpoint to goggles mounted over the eyes of experimental subjects, rapidly created the illusion in the experimental subjects that the other body or mannequin was their own body. This illusion was so compelling that it persisted even when the subjects (projected into the other bodies) shook hands with their own bodies. The existence of this illusion was demonstrated objectively by the fact that when the other (illusory own) body and one’s own body were both threatened with a knife, the emotional reaction (measured by heart rate and galvanic skin response) was greater for the illusory body. The well-known “rubber hand illusion” demonstrates the same relation between the self and the external body, albeit less dramatically. So does the inverse “phantom limb” phenomenon. (Solms and Panksepp)

22. Studies have shown that conscious awareness is necessary for some types of learning that give organisms additional plasticity to respond to new and novel stimuli in their environment.

- Our pain and sex lives might be regulated by unconscious information, but organisms need to learn. It is this that consciousness is for. It confers, like nothing else could, plasticity. Innate responses to basic evolutionarily advantageous or disadvantageous things might get us to mate or avoid standard bad things, but they wouldn’t get us to learn about the contingent features of our environment on which rests our ultimate success. (Flanagan and Polger) (Note: F&P don’t actually support this argument. They say “This argument won’t work. Plasticity, learning, and the like need not be, indeed in our own case they often are not, conscious.” However, the following studies show they are wrong for some types of learning.)

- Robert Clark and Larry Squire published the results of a classical Pavlovian conditioning experiment in humans. Two different test conditions were employed both using the eye-blink response to an air puff applied to the eye but with different temporal intervals between the air puff and a preceding, predictive stimulus (a tone): in one condition the tone remained on until the air puff was presented and both coterminated (“delay conditioning”); in the other a delay (500 or 1000 ms) was used between the offset of the tone and the onset of the air puff (“trace conditioning”). In both conditions experimental subjects were watching a silent movie while the stimuli were applied and questions regarding the contents of the silent movie and test conditions were asked after test completion. In the delay conditioning task, subjects acquired a conditioned response over 6 blocks of 20 trials: as soon as the tone appeared they showed the eye-blink response before the air puff arrived. This is a classical Pavlovian response in which a shift is noted from reaction to action, also known as specific anticipatory behaviour. This shift occurred whether subjects had knowledge of the temporal relationship between tone and air puff or not: both subjects who were aware of the temporal relationship — as judged by their answers to questions regarding this relationship after test completion — and subjects who were unaware of the relationship learned this experimental task. One could say that this type of conditioning occurs automatically, reflex-like, or implicitly. In contrast, the trace conditioning task required that the subjects explicitly knew or realized the temporal relationship between the tone and air puff. Only those subjects knowing this relationship explicitly — as judged by their answers to questions regarding this relationship — succeeded in performing the task; those that were not, failed. In other words, subjects had to be explicitly aware or have conscious knowledge of the task at hand in order to bring the shift about, that is, to respond after the tone and before the air puff. This is called explicit or declarative knowledge. … Clark and Squire (1998, p.79) suggested that “awareness is a prerequisite for successful trace conditioning”: (i) when explicitly briefed before trace conditioning about the temporal relationship between tone and air puff, all subjects learned the task, and faster than those without briefing; (ii) when performing an attention-demanding task, subjects did not acquire trace conditioning. (van den Bos)

23. An awareness of internal “emotions” allow us to learn from “feelings”.

- Feelings are mental experiences that are the conscious experience of emotions. (Post 10)

- Learning arises from associations between interoceptive drives and exteroceptive representations, guided by the feelings generated by the affective experiences aroused by those representations. This is why they become conscious; the embodied subject must evaluate them. (Solms and Panksepp)

- As the cognitive science of the late twentieth century is complemented by the affective neuroscience of the present, we are breaking through to a truly mental neuroscience, and finally understanding that the brain is not merely an information-processing device but also a sentient, intentional being. Our animal behaviors are not “just” behaviors; in their primal affective forms they embody ancient mental processes that we share, at the very least, with all other mammals. (Solms and Panksepp)

24. This learning can be repeated over and over in order to rebuild memories and learn new things from them in light of further information.

- The reversal of the memory consolidation process (reconsolidation; Nader et al., 2000) renders Long Term Memory-traces labile, through literal dissolution of the proteins that initially “wired” them (Hebb, 1949). This iterative feeling and re-feeling one's way through declarable problems is the function of the cognitive qualia which have so dominated contemporary consciousness studies. (Solms)

25. Conscious awareness of what is going on in our own minds goes hand in hand with developing awareness that others have minds.

- The study of which animals are capable of attributing knowledge and mental states to others, as well as the development of this ability in human ontogeny and phylogeny, has identified several behavioral precursors to theory of mind. Understanding attention, understanding of others' intentions, and imitative experience with other people are hallmarks of a theory of mind that may be observed early in the development of what later becomes a full-fledged theory. (Theory of Mind Wikipedia)

- Selfhood is impossible unless a self-organizing system monitors its internal state in relation to not-self dissipative forces. The self can only exist in contradistinction to the not-self. This ultimately gives rise to the philosophical problem of other minds. In fact, the properties of a Markov blanket explain the problem of other minds: the internal states of a self-organizing system can only ever register hidden external (not-system) states vicariously, via the sensory states of their own blanket. (Solms)

26. Once living organisms become aware of selves and others, simple forms of communication such as pointing develop.

- Joint attention refers to when two people look at and attend to the same thing; parents often use the act of pointing to prompt infants to engage in joint attention. The inclination to spontaneously reference an object in the world as of interest, via pointing, and to likewise appreciate the directed attention of another, may be the underlying motive behind all human communication. (Theory of Mind Wikipedia)

27. While sensory memory and pointing are enough for the self and for rudimentary communication, the development of language through abstract symbols allows for much greater scale and scope in cognition.

- On the “self-awareness being tied to language” note, I found this quote from Helen Keller interesting: “Before my teacher came to me, I did not know that I am. I lived in a world that was a no-world. I cannot hope to describe adequately that unconscious, yet conscious time of nothingness. (…) Since I had no power of thought, I did not compare one mental state with another.” Hellen Keller, 1908: quoted by Daniel Dennett, 1991, Consciousness Explained. London, The Penguin Press. pg 227 (Hiskey)

- Interestingly, deafness is significantly more serious than blindness in terms of the effect it can have on the brain. This isn’t because deaf people’s brains are different than hearing people, in terms of mental capacity or the like; rather, it is because of how integral language is to how our brain functions. To be clear, “language” here not only refers to spoken languages, but also to sign language. It is simply important that the brain have some form of language it can fully comprehend and can turn into an inner voice to drive thought. (Hiskey)

- Recent research has shown that language is integral in such brain functions as memory, abstract thinking, and, fascinatingly, self-awareness. Language has been shown to literally be the “device driver”, so to speak, that drives much of the brain’s core “hardware”. Thus, deaf people who aren’t identified as such very young or that live in places where they aren’t able to be taught sign language, will be significantly handicapped mentally until they learn a structured language, even though there is nothing actually wrong with their brains. The problem is even more severe than it may appear at first because of how important language is to the early stages of development of the brain. Those completely deaf people who are taught no sign language until later life will often have learning problems that stick with them throughout their lives, even after they have eventually learned a particular sign language. (Hiskey)

- Today I found out how deaf people think in terms of their “inner voice”. It turns out, this varies somewhat from deaf person to deaf person, depending on their level of deafness and vocal training. Those who were born completely deaf and only learned sign language will, not surprisingly, think in sign language. What is surprising is those who were born completely deaf but learn to speak through vocal training will occasionally think not only in the particular sign language that they know, but also will sometimes think in the vocal language they learned, with their brains coming up with how the vocal language sounds. Primarily though, most completely deaf people think in sign language. Similar to how an “inner voice” of a hearing person is experienced in one’s own voice, a completely deaf person sees or, more aptly, feels themselves signing in their head as they “talk” in their heads. (Hiskey)

- Interestingly, if you take a deaf person and make them grip something hard with their hands while asking them to memorize a list of words, this has the same disruptive effect as making a hearing person repeat some nonsense phrase such as “Bob and Bill” during memorization tasks. (Hiskey)

28. Language increases our ability to make sense of the world compared to working memory alone.

- Feeling only persists (is only required) for as long as the cognitive task at hand remains unresolved. Conscious cognitive capacity is an extremely limited resource (cf. Miller's law) which must be used sparingly. [Miller's law states that human beings are capable of holding seven-plus-or-minus-two units of information in working memory at any one point in time.] (Solms)

- Only consciousness allows us to entertain lasting thoughts. It also allows us to create algorithms, a step-by-step way of solving a problem. It allows for flexible routing of information and appears to be necessary for making a final decision. Consciousness is an important element of social information sharing. It condenses information, [making it easier to transfer]. (Post 9)

- If I ask you to picture a rope and climbing up it, you can do it. I specifically chose those objects and actions because it is exactly what a chimp in a zoo is familiar with. If I asked a chimp to do the same thing, could it? We don’t know, but I suspect not, because you can’t do it wordlessly. You need to be able to interact using language. Without language, I don’t think you have the cognitive systems for self-simulation and self-probing that we have. … Language allows us to be conscious of things we otherwise wouldn’t be able to be conscious of. (Post 7)

29. Language also vastly enlarges the recognition of patterns in the world, which is a vital part of our prediction abilities.

- Differences in knowledge yield striking differences in the capacity to pick up patterns. Expert chess players can instantly perceive (and subsequently recall with high accuracy) the total board position in a real game but are much worse at recall if the same chess pieces are randomly placed on the board, even though to a novice both boards are equally hard to recall. This should not surprise anyone who considers that an expert speaker of English would have much less difficulty perceiving and recalling: “The frightened cat struggled to get loose” than “Te serioghehnde t srugfcalde go tgtt ohle” which contains the same pieces, now somewhat disordered. Expert chess players, unlike novices, not only know how to Play chess; they know how to read chess—how to see the patterns at a glance. (Dennett)

30. Language enables deep and precise probing of the self.

- A particular human experience is where you know the experience is happening to you. We can’t rule that out in other animals, but neurological evidence suggests that it’s not happening. This “autonoetic consciousness” represents the view of the self as the subject. It enables mental time-travel (i.e. you can review past experiences and possible future states). Other animals can learn from the past, but in a simple way. (Post 12)

31. Language enables many more degrees of freedom. We may not have ultimately free will, but Libet’s attempt to deny it is a misunderstanding of the difference between the core affective self and the represented self of cognition.

- Degrees of freedom is something I’m using more lately. It is an opportunity for control. Degrees of freedom can be clamped or locked down to be removed. How many degrees of freedom do humans have? Millions and millions of things we can think of. We have orders of magnitude more that we can think of than a bear does, even with roughly the same number of cells. So, our complexity is higher. The options a bear has are a vanishing subset of the options that we have. Learning to control these options is not now a science. It is an art. (Dennett)

- Whereas homeostasis requires nothing more than ongoing adjustment of the system's active states (M) and/or inferences about its sensory states (ϕ), in accordance with its predictive model (ψ) of the external world (Q) or vegetative body (Qη), which can be adjusted automatically on the basis of ongoing registrations of prediction error (e), quantified as free energy (F)—contextual considerations require an additional capacity to adjust the precision weighting (ω) of all relevant quantities. This capacity provides a formal (mechanistic) account of voluntary behavior—of choice. (Solms)

- The unrecognized gap between the primary subjective self and the re-representational abstracted self causes much confusion. Witness the famous example of Benjamin Libet recording a delay of up to 400 ms between the physiological appearance of premotor activation and the voluntary decision to move. This is typically interpreted to mean that free will is an illusion, when in fact it shows only that reflexive re-representation of the self initiating a movement occurs somewhat later than the core self actually initiating it. (Solms and Panksepp)

32. Finally, language and the autobiographical self leads to all of the items of human culture.

- Autobiographical self has prompted: extended memory, reasoning, imagination, creativity, and language. Out of these came the instruments of culture: religions, justice, trade, the arts, science, and technology. (Post 10)

33. Bringing all of these aspects of consciousness together requires a multi-faceted framework. But it would help if this framework was organized around a single unifying concept.

- As long as one avoids confusion by being clear about one's meanings, there is great value in having a variety of concepts by which we can access and grasp consciousness in all its rich complexity. However, one should not assume that conceptual plurality implies referential divergence. Our multiple concepts of consciousness may in fact pick out varying aspects of a single unified underlying mental phenomenon. Whether and to what extent they do so remains an open question. (Consciousness Entry in Stanford Encyclopedia)

- The problem of consciousness will only be solved if we reduce its psychological and physiological manifestations to a single underlying abstraction. (Solms)

34. Before describing my own framework and unifying concepts, a quick review of some other contenders is helpful. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy lists six separate functions of consciousness.

- How do mental processes that involve the relevant sort of consciousness differ from those that lack it? What function(s) might consciousness play? The following six notions are some of the more commonly given answers: 1) Flexible control. Though unconscious automatic processes can be extremely efficient and rapid, they typically operate in ways that are more fixed and predetermined than those which involve conscious self-awareness. 2) Social coordination. Consciousness of the meta-mental sort may well involve not only an increase in self-awareness but also an enhanced understanding of the mental states of other minded creatures, especially those of other members of one's social group. 3) Integrated representation. Conscious experience presents us not with isolated properties or features but with objects and events situated in an ongoing independent world, and it does so by embodying in its experiential organization and dynamics the dense network of relations and interconnections that collectively constitute the meaningful structure of a world of objects. 4) Informational access. The information carried in conscious mental states is typically available for use by a diversity of mental subsystems and for application to a wide range of potential situations and actions. 5) Freedom of will. Consciousness has been thought to open a realm of possibilities, a sphere of options within which the conscious self might choose or act freely. 6) Intrinsic motivation. The attractive positive motivational aspect of a pleasure seems a part of its directly experienced phenomenal feel, as does the negative affective character of a pain. (Consciousness Entry in Stanford Encyclopedia)

35. A simple distinction is sometimes made between primary and higher order consciousness.

- Another theory about the function of consciousness has been proposed by Gerald Edelman called dynamic core hypothesis which puts emphasis on re-entrant connections (bi-directional connections) that reciprocally link areas of the brain in a massively parallel manner. Edelman also stresses the importance of the evolutionary emergence of higher-order consciousness in humans from the historically older trait of primary consciousness which humans share with non-human animals. (Consciousness Wikipedia)

- Primary consciousness is broken down into three elements: 1) Exteroceptive—Damasio’s mapping of the outer world. 2) Interoceptive—signals from inside the body. 3) Affective—the experience of feeling, emotion, or mood. (Post 11)

- The Ancient Origins of Consciousness does not address higher levels of consciousness: full-blown self-awareness, meta-awareness, recognition of the self in mirrors, theory of mind, access to verbal self-reporting. (Post 11)

36. Another widely discussed definition divides consciousness into three forms: anoetic, noetic, and autonoetic.

- In short, the complexity of our capacity to consciously and unconsciously process fluctuating brain states and environmentally linked behavioral processes requires some kind of multi-tiered analysis, such as Endel Tulving’s well-known parsing of consciousness into three forms: anoetic (unthinking forms of experience, which may be affectively intense without being “known”, and could be the birthright of all mammals), noetic (thinking forms of consciousness, linked to exteroceptive perception and cognition), and autonoetic (abstracted forms of perceptions and cognitions, which allow conscious “awareness” and reflection upon experience in the “mind’s eye” through episodic memories and fantasies). (Solms and Panksepp)

37. This is similar to Antonio Damasio’s three selves.

- A mind emerges from the brain when an animal is able to create images and to map the world and its body. [According to Antonio Damasio’s definition,] consciousness requires the addition of self-awareness. This begins at the level of the brain stem, with “primordial feelings.” The self is built up in stages starting with the proto self made up of primordial feelings, affect alone, and feeling alive. Then the core self is developed when the proto self is interacting with objects and images such that they are modified and there is a narrative sequence. Finally comes the autobiographical self, which is built from the lived past and the anticipated future. (Post 10)

38. Feinberg and Mallat list six adaptive advantages of consciousness organized over three different levels.

- Adaptive advantages of consciousness: 1) It efficiently organizes much sensory input into a set of diverse qualia for action choice. As it organizes them, it resolves conflicts among the diverse inputs. 2) Its unified simulation of the complex environment directs behaviour in three-dimensional space. 3) Its importance-ranking of sensed stimuli, by assigned affects, makes decisions easier. 4) It allows flexible behaviour. It allows much and flexible learning. 5) It predicts the near future, allowing error correction. 6) It deals well with new situations. (Feinberg and Mallatt)

- The Defining Features of Consciousness are: Level 1) General Biological Features: life, embodiment, processes, self-organizing systems, emergence, teleonomy, and adaption. Level 2) Reflexes of animals with nervous systems. Level 3) Special Neurobiological Features: complex hierarchy (of networks); nested and non-nested processes, aka recursive; isomorphic representations and mental images; affective states; attention; and memory. (Post 11)

39. The latest hierarchy from Mike Smith on his excellent Self Aware Patterns website (which devotes a lot of time to consciousness studies) has six layers.

- Matter: a system that is part of the environment, is affected by it, and affects it. Panpsychism.

- Reflexes and fixed action patterns: automatic reactions to stimuli. If we stipulate that these must be biologically adaptive, then this layer is equivalent to universal biopsychism.

- Perception: models of the environment built from distance senses, increasing the scope of what the reflexes are reacting to.

- Volition: selection of which reflexes to allow or inhibit based on learned predictions.

- Deliberative imagination: sensory-action scenarios, episodic memory, to enhance 4.

- Introspection: deep recursive metacognition enabling symbolic thought.

40. Lyon lists 13 functional abilities of cognition that help organisms adapt to their environment.

- The broadly biological conceptions of the capacities encompassed by the general concept of cognition are: (1) sense perception — ability to recognize existentially salient features of the external or internal milieu; (2) affect — valence: attraction, repulsion, neutrality / indifference (hedonic response); (3) discrimination — ability to determine that a state of affairs affords an existential opportunity or presents a challenge, requiring a change in internal state of behavior; (4) memory — retention of information about a state of affairs for a non-zero period; (5) learning — experience-modulated behavior change; (6) problem solving / decision making — behavior selection in circumstances with multiple, potentially conflicting parameters and varying degrees of uncertainty; (7) communication — mechanism for initiating purposive interaction with conspecifics (or non-conspecific others) to fulfil an existentially salient goal; (8) motivation — teleonomic striving; implicit goals arising from existential conditions; (9) anticipation — behavioral change based on experience-based expectancy (i.e. if X is happening, then Y should happen), possibly evolved across generations, and which is implicit to the agent’s functioning; (10) awareness — orienting response; ability to selectively attend to aspects of the external and/or internal milieu; (11) self-reference — mechanisms for distinguishing “self” or “like self” from “non-self” or “not like self”; (12) normativity — error detection, behavioral correction, value assignment based on motivational state; (13) intentionality — directedness towards an object. (Lyon)

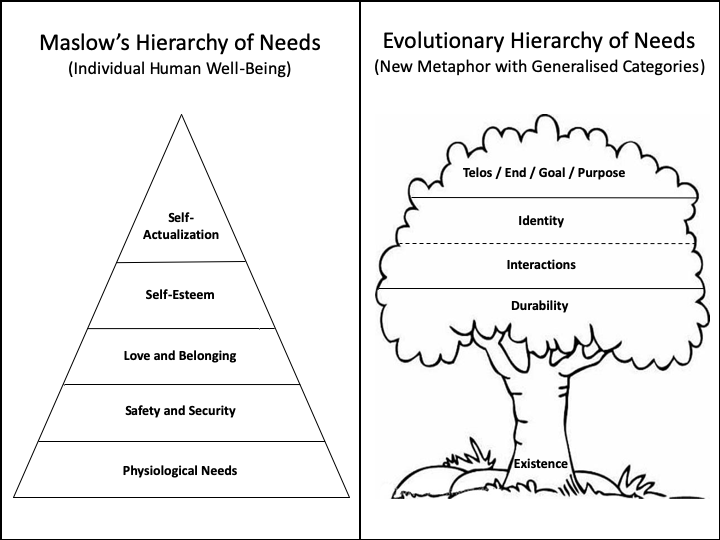

41. These adaptations help meet the evolutionary hierarchy of needs of all life.

- The evolutionary perspective of our diverse and ever-changing web of life transforms Maslow’s hierarchy. Starting at the bottom of the pyramid—or tree now—we see that the “physiological” needs of the human are merely the brute ingredients necessary for “existence” that any form of life might have. In order for that existence to survive through time, the second level needs for “safety and security” can be understood as promoting “durability” in living things. The third tier requirements for “love and belonging” are necessary outcomes from the unavoidable “interactions” that take place in our deeply interconnected biome of Earth. The “self-esteem” needs of individuals could be seen merely as ways for organisms to carve out a useful “identity” within the chaos of competition and cooperation that characterizes the struggle for survival. And finally, the “self-actualization” that Maslow struggled to define (and which Kenrick and Andrews discarded or subsumed elsewhere), could be seen as the end, goal, or purpose that an individual takes on so that they may (consciously or unconsciously) have an ultimate arbiter for the choices that have to be made during their lifetime. This is something Aristotle called “telos.” Putting this all together, we may then change Maslow’s hierarchical pyramid of human needs into the following multi-layered tree for any individual life. (Gibney)

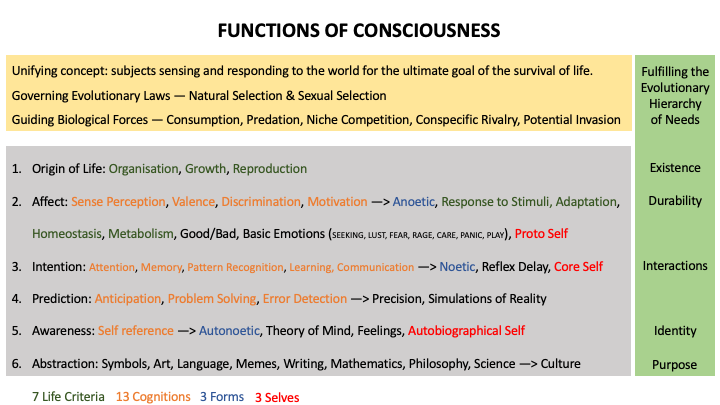

42. Summarising all of this research, here is my proposal for a hierarchy of the functions of consciousness. They are unified under a single concept, governed by the evolutionary laws of selection, and guided by biological forces in order to meet the needs of life.

In my proposal, understanding consciousness begins with the unifying concept of “subjects sensing and responding to the world for the ultimate goal of the survival of life.” This is in line with how I define consciousness (derived from the Latin for “knowing together”). The functions that evolve are governed by the laws of natural selection and (later) sexual selection. They are guided in this evolution by the biological forces that exerted on living beings: consumption, predation, niche competition, conspecific rivalry, and potential invasion. And they help organisms meet their evolutionary hierarchy of needs.

Stepping through the hierarchy, we therefore start with the origin of life. Once the first three criteria from the general definition for life are happening—organisation, growth, and reproduction—subjects come into existence.

As soon as life emerges, the function of affect begins to take hold. Any changes to these living organisms cause chemical forces to be exerted on individual subjects. Changes that lead towards persistence are objectively defined as good. The opposite changes are bad. Stability is homeostasis. As these changes are selected for, the earliest forms of life become more complex, eventually meeting the rest of the criteria for the definition of life—response to stimuli, adaptation, homeostasis, and metabolism. These forms of life respond reflexively, using chemical emotional responses alone that develop (according to Panksepp) into seven basic emotions: foraging for resources (SEEKING), reproductive drive (LUST), protection of the body (FEAR and RAGE), maternal devotion (CARE), separation distress (PANIC), and vigorous positive engagement with conspecifics (PLAY). The first four of these have premammalian origins. In humans, the final three only date back to early primates. Among the 13 cognitive capacities that Lyon notes, 4 are required during this stage of affect: sense perception, valence, discrimination, and motivation. These can be said to produce the anoetic, proto self.

Over time, adaptations from affective reflexes alone lead to capacities for cognition that are able to interrupt these reflexes. From Lyon’s list, the five capacities of attention, memory, pattern recognition, learning, and communication lead to this noetic, core self where organisms can be said to be acting with intention. Choices are made and to an outside observer there is a narrative sequence to life.

Once intentions exist (either one’s own or the intentions of others), they can be taken into account. To do so is to use prediction to think through what the result will be from any intentions. This requires three more cognitive capacities from Lyon’s list: anticipation, problem solving, and error detection. With these abilities, organisms can simulate reality and be led by emotions of precision to hone these simulations towards greater accuracy.

As predictions and perceptions improve, organisms eventually make the connection that there is a self which has its own mind. Awareness is achieved. This development is covered by the final cognitive capacity from Lyon’s list: self-reference. Such conscious cognition allows memories and thoughts built from the lived past and the anticipated future to create the autonoetic, autobiographical self.

Finally, through the development of ideas about the self and other minds, brains began to imagine something that had no immediate impact on their senses. This opens up the doors for much further abstraction. Slowly, the evolution of symbols, art, and language took place, enabling certain abilities that perhaps only humans possess at this time. Memes, writing, mathematics, philosophy, and science make up and enable all of eventual the products of human culture.

So, there you have it. As I noted in my brief history of the definitions of consciousness, many, many attempts have been made at this. Maybe this is just another one. But I believe it is the kind of comprehensive definition that would allow others to draw circles around the items from their definitions and say, “that’s what I think consciousness is.” If I’m lucky, maybe they’ll even switch to say, “that’s what I thought consciousness was.”

The hard problem of consciousness is often phrased as wondering how inert matter can ever evolve into the subjective experience that we humans undoubtedly feel. I think this short-changes matter. Far from being inert, matter responds to the forces exerted on it all the time. Panpsychism says mind (psyche) is everywhere. But to me there can be no mind without a stable subject. In my current conception, the forces that minds feel and are shaped by are merely the chemical and physical forces that shape all matter. Until something else is found, what else could there be? So, mind is not everywhere, but forces are. The Greek for force is dynami, so rather than panpsychism, I would say the universe has pandynamism. The psyche only originates and evolves along with life.

What about other forms of non-biological life? As I said in post 17, “Could artificial life also respond to these forces and be declared conscious? I think yes, although the “feeling of what it is like” to be such life would be very different from current biological life forms that are built from organic chemistry. We already believe the feeling of what is like to be a bat is likely very different from that of a cuttlefish, so the difference would be even greater for artificial life given the much larger change in underlying mechanisms. Yet both could be considered conscious in my definition.”

And with that, I have my answer to the 1st of Tinbergen’s 4 questions about the biological aspects of consciousness. Now that we have a clear list of the functions that consciousness enables, I’ll try to match them up against the mechanisms that cause all of this. Stay tuned for that as the end of this series comes into view.

--------------------------------------------

Previous Posts in This Series:

Consciousness 1 — Introduction to the Series

Consciousness 2 — The Illusory Self and a Fundamental Mystery

Consciousness 3 — The Hard Problem

Consciousness 4 — Panpsychist Problems With Consciousness

Consciousness 5 — Is It Just An Illusion?

Consciousness 6 — Introducing an Evolutionary Perspective

Consciousness 7 — More On Evolution

Consciousness 8 — Neurophilosophy

Consciousness 9 — Global Neuronal Workspace Theory

Consciousness 10 — Mind + Self

Consciousness 11 — Neurobiological Naturalism

Consciousness 12 — The Deep History of Ourselves

Consciousness 13 — (Rethinking) The Attention Schema

Consciousness 14 — Integrated Information Theory

Consciousness 15 — What is a Theory?

Consciousness 16 — A (sorta) Brief History of Its Definitions

Consciousness 17 — From Physics to Chemistry to Biology

Consciousness 18 — Tinbergen's Four Questions