The body and the mind are inseparable. Minds arise from bodies, and bodies can be affected by the mind. This psychosomatic link introduces other concepts - emotion, needs and desires, and personality - that need to be mastered for life to thrive. As an organism with a mind-body connection, a sound mind builds a sound body and vice versa.

The first of these mind-body connections that I would like to examine are our emotions. These are complex feelings that have been explored by poets and philosophers for millennia, but what exactly are they talking about? First, let's turn to the science of biology for a definition of emotion:

Emotion is a complex psychophysiological experience where an individual's state of mind interacts with biochemical (internal) and environmental (external) influences. Emotions can be seen as mammalian elaborations of general vertebrate arousal patterns, in which neurochemicals (for example, dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin) step-up or step-down the brain's activity level, as visible in body movements, gestures, and postures.

From this, we understand that emotions are, in a sense, mere chemical changes in the brain that act to encourage our behavior. From fight or flight, to mania or depression, to steady effort or distracted pausing, to certain striding or confused questioning; our emotions fuel our actions. But what causes these chemical changes? Do they arise from the ether? Or a raging subconscious world we have no access to? Well actually, our best current understanding of emotion comes from the field of cognitive psychology. Specifically:

An influential theory of emotion is that of Lazarus: emotion is a disturbance that occurs in the following order: 1) cognitive appraisal - the individual assesses the event cognitively, which cues the emotion; 2) physiological changes - the cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response; 3) action - the individual feels the emotion and chooses how to react. Lazarus stressed that the quality and intensity of emotions are controlled through cognitive processes.

Think about this for a moment. Say you have a painful fear of spiders. If one were to silently crawl behind you, you would feel absolutely no fear. Even if the spider was dangerously close to you. Your body does not get scared of an unseen spider until you actually see it - until you "assess the event cognitively." Then the pounding heartbeat and sweaty palms that accompany the fearful fight or flight response kick in. Now let's suppose that you see a ball of dust that you mistake for a spider. Your fear kicks in at the first cognitive thought, "that is a spider!" But as your brain recognizes the fact that it is not really a spider, but only a harmless speck of dust, then your new updated cognitive appraisal of the situation changes your emotional response. You lose the fight or flight kick of adrenaline and get back to whatever it was that you were doing.

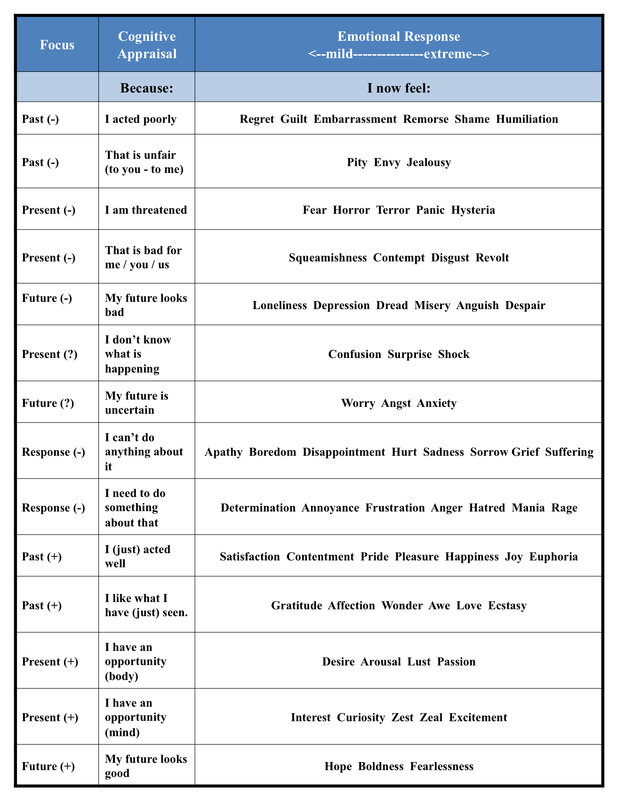

Now, what kind of cognitive assessments can you make? Using our logical system of finding a MECE (mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive) framework to analyze your assessments, we can come up with something new and unique to understand our emotions. Specifically, I say:

No definitive emotion classification system exists, though numerous taxonomies have been proposed. I propose the following system. Given that emotions are responses to cognitive appraisals, they can be classified according to what we are appraising. In total, we can think about the past, present, or future, and we can judge events to be good or bad, or we can be unsure about them. We can also appraise our options for what to do about negative feelings (positive emotions need no immediate correction). Finally, our emotional responses can range from mild to extreme. A list of emotions might therefore be understood through the following table.