By my count, this is the 27th thought experiment out of the 63 I've covered so far that touches upon epistemology, aka the study of knowledge. I'm sure it has felt repetitive and excessive to address this over and over (it sure has to me!), but there's a good reason that it preoccupies philosophers so deeply. Knowledge is pretty much the core concept for the field, but philosophers still don't have an accepted definition of it.

Usually, when a question about this comes up, I like to quote that Plato defined knowledge as justified true belief, or point out that Hume said "A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence." We all pretty much get this because, pragmatically, we live our lives by these rules. It's what led me to define my second tenet like this:

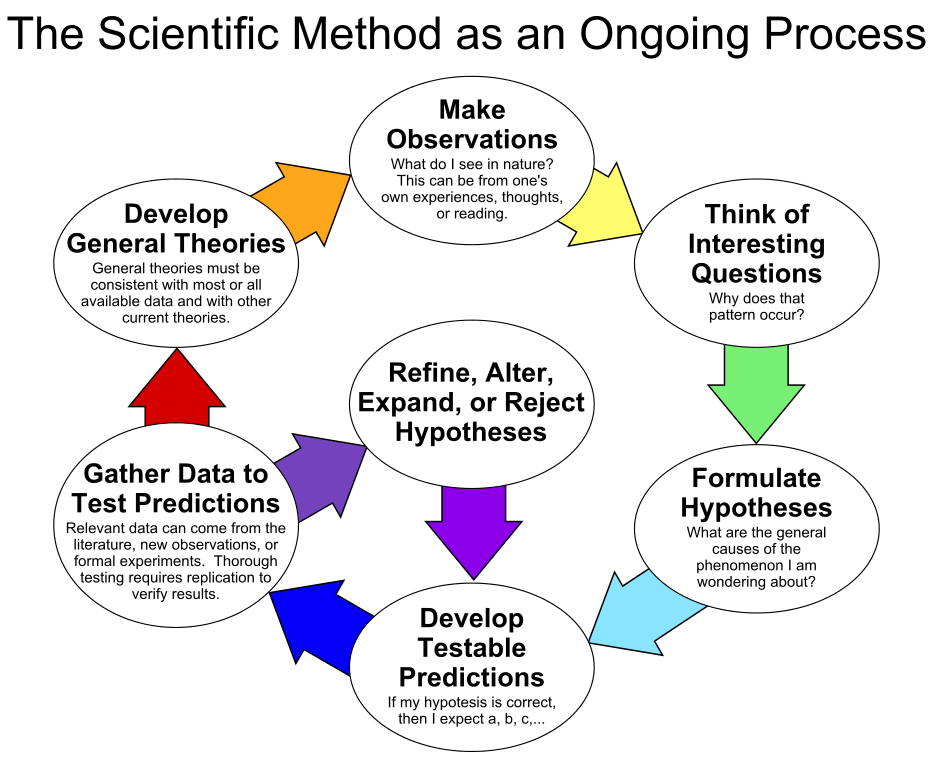

2. Knowledge comes from using reason to understand our sense experiences. The iterative nature of the scientific method is what hones this process towards truth. In a large and changing universe, eternal absolutes are extremely difficult to prove. We must act based on the best available knowledge. This leaves us almost entirely with probabilistic knowledge, which means we must act with confidence and caution appropriate to the probability, being especially careful in realms where knowledge is uncertain and consequences of error are large.

Now, after covering so many thought experiments rooted in skepticism like the ones about evil demons, nightmares, rocking horses, invisible gardeners, rabbits, divine commands, color vision, mozzarella moons, and fragmented momentary identities, I must make a few changes to that tenet in order to make it more exact. Due to the existence of hyperbolic doubt that casts its ugly shadows on all knowledge, I would change "extremely difficult to prove" to "impossible to prove now," and I would drop the word "almost" from the fifth sentence, which "leaves us entirely with probabilistic knowledge."**

(** By the way, when I say probabilistic, I don't mean probabilities that are calculable after the fact like in regular statistics, or even probabilities that are estimated ahead of time and then revised along the way as in Bayesian statistics. When I say knowledge is probabilistic, I mean like this definition of probabilism: (noun, as used in philosophy) the doctrine, introduced by the Skeptics, that certainty is impossible and that probability suffices to govern faith and practice.)

I consider these small edits simple deletions of the slight prevarications in my original text, so up till now I've been happy to keep answering previous thought experiments about knowledge by just saying it is probabilistic and then moving on. But now it's time to dig into this a little deeper. While I'm here, I should also address another potential for misunderstanding from my original tenets. In the very first one, I said the following:

1. We live in a rational, knowable, physical universe. Effects have natural causes. No supernatural events have ever been unquestionably documented.

I originally thought of tenet #2 as putting a qualifier on just how knowable the universe is in tenet #1, but I can see now that since I'm claiming all knowledge is probabilistic, someone might ask how I can claim the universe is in fact knowable at all. As I was preparing for this blog, I heard a good explanation for this from professor John Searle (he, of the Chinese Room thought experiment) in a podcast debate called After the End of Truth. During that talk, he pointed out how there is a distinction to be made between ontology (the nature of being, of what is) and epistemology (what we know, what we can know). My first tenet claims that--ontologically--the universe is real. This means there is one objective reality that does not spontaneously mutate in any supernatural ways. Unfortunately, my second tenet states that--epistemologically—all of our knowledge can only ever be subjective, for reasons I've explored in other thought experiments and will do so again below. So, my first claim, that there is one objective reality, can really only be known provisionally. It must be an assumption. I would even go so far as to call it: the first assumption. I'll come back to this at the end of the post, but now that that clarification is out of the way, let's turn to the epistemological knowledge problem in this week's thought experiment.

---------------------------------------------------

It was a very strange coincidence. One day last week, while Naomi was paying for her coffee, the man behind her, fumbling in his pockets, dropped his key ring. Naomi picked it up and couldn't help but notice the small white rabbit dangling from it. As she handed it back to the man, who had a very distinctive, angular, ashen face, he looked a little embarrassed and said, "I take it everywhere. Sentimental reasons." He blushed and they said no more.

The very next day she was about to cross the road when she heard a screeching of brakes and then an ominous thud. Almost without thinking, she was drawn with the crowd to the scene of the accident, like iron filings collecting around a magnet. She looked to see who the victim was and saw that same white, jagged face. A doctor was already examining him. "He's dead."

She was required to give a statement to the police. "All I know is that he bought a coffee at that cafe yesterday and that he always carried a key ring with a white rabbit." The police were able to confirm that both facts were true.

Five days later Naomi almost screamed out loud when, queuing once more for her coffee, she turned to see what looked like the same man standing behind her. He registered her shock but did not seem surprised by it. "You thought I was my twin brother, right?" he asked. Naomi nodded. "You're not the first to react like that since the accident. It doesn't help that we both come to the same cafe, but not usually together."

As he spoke, Naoimi couldn't help staring at what was in his hands: a white rabbit on a key ring. The man was not taken aback by that either. "You know mothers. They like to treat their kids the same."

Naomi found the whole experience disconcerting. But the question that bothered her when she finally calmed down was: has she told the police the truth?

Source: "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?" by E. Gettier, republished in Analytic Philosophy: An Anthology, 2001.

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 187.

---------------------------------------------------

This sounds absolutely innocuous, doesn't it? From a legal perspective, Naomi is perfectly fine because her identification of the body was totally reasonable. (Reasonable being a key word in the legal definition of knowledge.) Under ordinary circumstances, with no creepily identical twin walking around out there, the matter would be over. But in this extraordinary case, the details surrounding her statement to the police means that the whole situation strikes at the heart of the definition of knowledge that had been widely accepted by philosophers for literally thousands of years. As I said above, it was Plato who defined knowledge as:

- justified

- true

- belief.

I've written those in a numbered list to help emphasise the importance and independence of each one of those three variables. As it had traditionally been explained, you couldn't KNOW something (written in capital letters to denote the philosophical usage of the term) unless you possessed all three elements. For example, let's say you think you KNOW the Earth is round. The reason you think so, though, is because you live on a high rounded hill and the world looks like it slopes away from you very smoothly in all directions. If that's your justification, then you don't really KNOW the Earth is round. Your knowledge would leave you as soon as you grew up and walked down the hill. Next, let's be jerks and insist that the Earth is actually slightly oblong. In that case, it's no longer true that the Earth is round, so you can't KNOW that it is, because you'd be wrong. It's oblong. But finally, let's go back to accepting that the world is roughly round, and you've been taught in school that it is. However, you're the jerk now and you just don't accept that. You could pass along a justification for the truth to someone else, but you don't KNOW it since you don't believe it. You see? Knowledge is justified, true, belief.

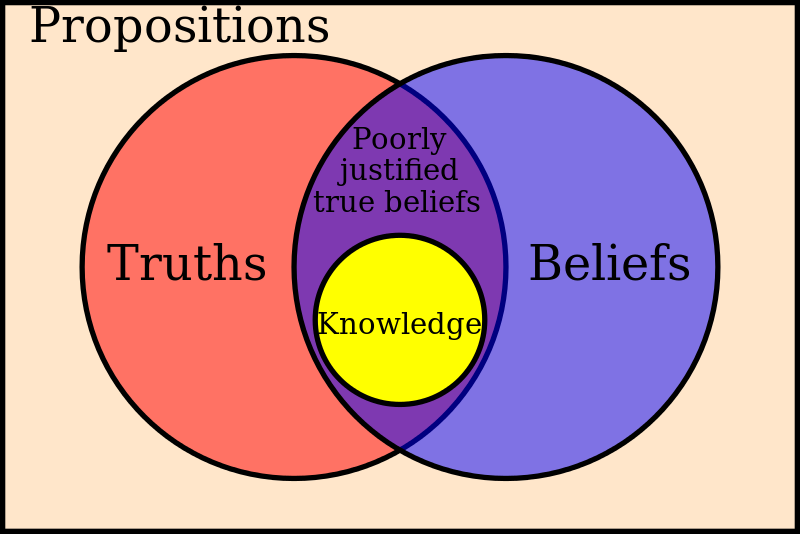

Or at least, it was. For philosophers of epistemology, "the definition of knowledge as justified true belief was widely accepted until the 1960s. At this time, a paper written by the American philosopher Edmund Gettier provoked major widespread discussion. Gettier contended that while justified belief in a true proposition is necessary for that proposition to be known, it is not sufficient. As in the diagram [below], a true proposition can be believed by an individual (purple region) but still not fall within the "knowledge" category (yellow region). According to Gettier, there are certain circumstances in which one does not have knowledge, even when all of the above conditions are met. These cases fail to be knowledge because the subject's belief is justified, but only happens to be true by virtue of luck. In other words, he made the correct choice for the wrong reasons."

"Naomi didn't know because her justification for claiming to know the two facts about the dead man was not strong enough. But if this is true, then we need to demand that knowledge has very strict conditions for justification of belief across the board. And that means we will find that almost all of what we think we know is not sufficiently justified to count as knowledge."

The difficulty in finding such justifications is notoriously known by two related problems in philosophy: the regress problem and the problem of induction. Both of these show that so far we have found it impossible to fully justify a solid basis for our knowledge. Going backwards, the regress problem states that "the traditional way of supporting a rational argument is to appeal to other rational arguments, typically using chains of reason and rules of logic. [But] how can we eventually terminate a logical argument with some statement(s) that do not require further justification but can still be considered rational and justified?" There have been many attempts to solve this, but to make a long philosophy story short, we can't. And the difficulty is just as bad going forward. In that direction, the problem of induction--which is most associated with David Hume—states that "from a series of observations it seems valid to infer [the observations will continue. But] it is not certain, regardless of the number of observations. In fact, Hume would even argue that we cannot claim it is 'more probable', since this still requires the assumption that the past predicts the future. [Also], the observations themselves do not establish the validity of inductive reasoning, except inductively." Hume noted that we use the inductive method to predict the future all the time, and that most of the time it works, but it is not infallible because ultimately it is just circular.

I said above in my tenet #2 that the universe is too large to know everything, but that seems like something that could theoretically be overcome. Really, the ultimate reason for the impossibility of knowing everything is because of time. The past behind the Big Bang is currently unknowable, and the future seems like it will be unknowable forever. Of all the dozens of Gettier problems that have been dreamed up by philosophers to show that justified, true, belief (JTB) is not sufficient for knowledge, the one that Baggini chose to use in this thought experiment is well suited to illustrate the futileness of our attempts to KNOW. As we see, Naomi had a reasonable JTB, but someone came along later and gave her extraordinary new facts that rendered her previous belief false. Well, since we can never know the future, all knowledge is like that. Invoking the most extreme skepticism, an evil demon is always lurking out there that could change what we think we know. In light of the two historical problems of justifying knowledge, we are forced into a position of skepticism, which questions the validity of all human knowledge. This is best known by Socrates' statement that the only thing he knew was that he knew nothing with certainty.

The fields of logic and math have lured philosophers into believing that some truths must be eternal everywhere, but even these might be dependent upon one's place in the universe. Take, for example, the perspective one would have in a black hole where the extreme force of gravity forces everything, even light, into a singularity. In such a realm, nothing would ever logically be "either/or." Everything would become "both/and" as soon as they entered the discussion. Two plus two would not equal four. Two entities would always become one. Two plus two would still end up as one. Math tests would become trivially easy as every answer would just be one! Of course, this is a slightly facetious conjecture because no philosopher or mathematician could survive in such a situation to develop these rules of math and logic, but I think this does show that even our most certain knowledge might be subject to change in another time or place in this or another universe.

So what do we do about all this?

In the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on these so-called Gettier problems, it is noted that these thought experiments, "sparked a period of pronounced epistemological energy and innovation. ... Since 1963 epistemologists have tried — again and again and again — to revise or repair or replace JTB in response to Gettier cases. ... There is no consensus, however, that any one of the attempts to solve the Gettier challenge has succeeded in fully defining what it is to have knowledge of a truth or fact. ... This might have us wondering whether a complete analytical definition of knowledge is even possible."

You can read more details on the philosophical history of this problem at the link in that previous paragraph (or you could also go here, or here), but rather than hash through all of the various attempted responses — which fall into three main categories: 1) undermining Gettier; 2) adding a fourth condition to JTB; or 3) revising the J in JTB — I think it's plain from my analysis above that no solution has been reached precisely because a complete analytical definition of knowledge is not possible. In ancient times, humans believed the universe (or at least their gods and their heavens) were eternal, fixed, and immutable. This is the type of environment that is required for TRUTH to exist. Pragmatically, over timespans of human existence, such an environment can seem like it exists, but over evolutionary time, we now see that our universe is temporal (not eternal), expanding (not fixed), and changing (not immutable). In this type of environment, we can never be certain that any TRUTH will survive. Knowledge, therefore, cannot be justified true belief, because there is no such thing as TRUTH. When looking at the JTB account of knowledge, It is the T that must be revised because our cosmological revolution needs to sink in to our epistemological understanding.

Before we get to T's replacement, let's look quickly at J and B. The question of Belief is a straightforward one that any honest person can answer about themselves either to themselves or to another. (Of course, changing beliefs is another matter entirely...) As for Justification, the best method we have found so far is the scientific method, which consists of systematic observation, measurement, and experimentation, in conjunction with the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses. Under modern interpretations, a scientific hypothesis must also be falsifiable, otherwise the hypothesis cannot be meaningfully tested.

So what then is the best way to define knowledge? It can't be a perfectly complete and TRUE thing. It must be an ongoing process that is forever subject to change. As long as there is no reason for knowledge to change, it can persist, it can survive. Like anything, knowledge is therefore subject to evolutionary forces. It varies. It is selected for its fit. And if the facts of the environment change, then it either adapts or goes extinct. No "truth" is ever permanently immutable. Not even that one. Some day, some evil demon might reveal itself and prove that some truths are permanent, but until then, we must live and rely on the knowledge that survives our best examinations.

When do we know that knowledge is surviving? Whenever knowledge holds up while trying to make predictions with it. Where beliefs fail to predict, they are discarded. In a process that is akin to the variation, selection, and retention model of natural selection in biological evolution, we can call this rational selection within the evolution of knowledge. For evolutionary epistemologists, all theories are "true" only provisionally, regardless of the degree of empirical testing they have survived. I believe this is the best way we currently have, or may ever have, of looking at the world. Therefore:

Knowledge can only ever be: justified, beliefs, that are surviving.

In this, my JBS Theory of Knowledge, propositions are either surviving or they have gone extinct after having passed or failed a number of rational selections. Just as billions and billions of iterations of natural selection have shaped all of life, billions and billions of iterations of rational selection have honed knowledge. The more successful passes through rational selection that have been made (e.g. over greater numbers of years, numbers of people, numbers of experiments, and diversity for all of these), the more robust that knowledge can become. However, no knowledge is ever safe from the threat of extinction. This is equivalent to the robustness of life surviving through numerous environmental conditions, but always needing to adapt if conditions change.

Finally, this brings us back to tenet #1, our first assumption. Through the eons of the entire age of life, and over all the instances of individual organisms acting within the universe, the ability of life to predict its environment and continue to survive in it has required that ontologically the universe must be singular, objective, and knowable. If it were otherwise, life could not make sense of things and survive here. As we now see, we may never know if that is TRUE, but so far that knowledge has survived. The objective existence of the universe may indeed be an assumption, but as a starting point, it now seems to be the strongest knowledge we have.