—Stephen Hawking in A Brief History of Time

The later Wittgenstein, on the contrary, seems to have grown tired of serious thinking and to have invented a doctrine which would make such an activity unnecessary. --Bertrand Russell

A good guide will take you through the more important streets more often than he takes you down side streets; a bad guide will do the opposite. In philosophy I'm a rather bad guide. —Ludwig Wittgenstein

Current philosophical camps

Analytic Philosophy - In the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Scandinavia, Australia, and New Zealand, the overwhelming majority of university philosophy departments identify themselves as "analytic" departments. Analytic philosophy is often understood as being defined in opposition to continental philosophy. The term "analytic philosophy" can refer to a tradition of doing philosophy characterized by an emphasis on clarity and argument, often achieved via modern formal logic and analysis of language, and a respect for the natural sciences. In this sense, analytic philosophy makes specific philosophical commitments: 1) The positivist view that there are no specifically philosophical truths and that the object of philosophy is the logical clarification of thoughts. This may be contrasted with the traditional foundation that views philosophy as a special sort of science, the highest one, which investigates the fundamental reasons and principles of everything. As a result, many analytic philosophers have considered their inquiries as continuous with, or subordinate to, those of the natural sciences. 2) The view that the logical clarification of thoughts can only be achieved by analysis of the logical form of philosophical propositions. The logical form of a proposition is a way of representing it (often using the formal grammar and symbolism of a logical system) to display its similarity with all other propositions of the same type. However, analytic philosophers disagree widely about the correct logical form of ordinary language. 3) The rejection of sweeping philosophical systems in favor of close attention to detail, common sense, and ordinary language.

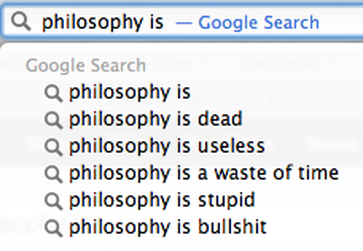

Philosophers may stand on surer ground when they focus on logic and the analysis of words in arguments, and these are surely vital building blocks for anyone to use in the pursuit of knowledge, but for this to dominate the field as it now does takes its practitioners a long way away from the original "love of wisdom" that Pythagoras intended when he first invented the word philosophy. I get it though. Nietzsche had rightly observed that "God is Dead", so there was no need to re-plow the land medieval philosophers had dug up by speculating about theological metaphysical origins. Physics and the natural sciences had taken over the search for our natural metaphysical origins. And Hume's "is/ought" divide meant that no headway could ever be made about what was right or wrong in this world, meaning further arguments about ethics, aesthetics, or politics were doomed and essentially fruitless. Hopefully that will change soon, but in the meantime, philosophers throw up their hands and respect proclamations from Wittgenstein like:

It is one of the chief skills of the philosopher not to occupy himself with questions which do not concern him.

The difficulty in philosophy is to say no more than we know.

What can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.

Philosophy aims at the logical clarification of thoughts. Philosophy is not a body of doctrine but an activity.

And yet, when thoughts are clarified, does the body of a doctrine not form? If not, if the thoughts still leave a fuzzy view of the world, then the thoughts require further clarification. I obviously think this is possible since I've posted my own doctrine here for discussion and clarification, but I wish more philosophers would join in. Until they do, let's look at how Wittgenstein's works hold up against the doctrine I'm elaborating through my survival of the fittest philosophers series.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951 CE) was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. Wittgenstein is considered by many to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century.

Survives

After the completion of his first book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1918, Wittgenstein believed he had solved all the problems of philosophy and he abandoned his studies. However, in 1929 he returned to Cambridge and began the meditations that ultimately led him to renounce or revise much of his earlier work, rejecting the analytical fantasy that a philosophical language could be derived mathematically from first principles, in favor of a more descriptive linguistic philosophy. This change of mind culminated in his second magnum opus, the Philosophical Investigations, which was published posthumously. In it, Wittgenstein asks the reader to think of language as a multiplicity of language-games within which parts of language develop and function. He argues philosophical problems are bewitchments that arise from philosophers' misguided attempts to consider the meaning of words independently of their context, usage, and grammar, what he called "language gone on holiday.” According to Wittgenstein, philosophical problems arise when language is forced from its proper home into a metaphysical environment, where all the familiar and necessary landmarks and contextual clues are removed. He describes this metaphysical environment as like being on frictionless ice: where the conditions are apparently perfect for a philosophically and logically perfect language - the language of the Tractatus - where all philosophical problems can be solved without the muddying effects of everyday contexts; but where, precisely because of the lack of friction, language can in fact do no work at all. Wittgenstein argues that philosophers must leave the frictionless ice and return to the "rough ground" of ordinary language in use. Ordinary language is the easiest way to express penetrating insight. Abstruse language is the sign of an obtuse mind.

Needs to Adapt

Gone Extinct

Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is probably most well known for the logical atomism that Russell himself stressed in it: the picture theory of meaning. The world consists of independent atomic facts - existing states of affairs - out of which larger facts are built. Language consists of atomic, and then larger-scale, propositions that correspond to these facts by sharing the same logical form. Thought, expressed in language, "pictures" these facts. Wittgenstein himself later recanted these beliefs. This is more logical-grammatical acrobatics that ended up upside down.

The whole sense of the Wittgenstein’s first book might be summed up in the following words: what can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence. Those things that cannot be expressed in words make themselves manifest; Wittgenstein calls them the mystical. They include everything that is the traditional subject matter of philosophy, because what can be said is exhausted by the natural sciences. Philosophy is not one of the natural sciences. The word philosophy must mean something whose place is above or below the natural sciences, not beside them. Philosophy helps us guide, categorize, and understand the natural sciences. The natural sciences inform philosophers about the big questions they are asking. The two fields are intertwined and supportive of one another, just as all life supports and is intertwined with other life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Wittgenstein came from quite a unique background, and in many ways one wouldn't expect him to have become a philosopher known primarily for logic. Wittgenstein's father Karl was an industrial tycoon who, by the late 1880s, "was one of the richest men in Europe, with an effective monopoly on Austria's steel cartel. Thanks to Karl, the Wittgensteins became the second wealthiest family in Austria-Hungary, behind only the Rothschilds." Ludwig was one of nine children who "were raised in an exceptionally intense environment. The family was at the center of Vienna's cultural life. Karl was a leading patron of the arts, commissioning works by Auguste Rodin and financing the city's exhibition hall and art gallery—the famous Secession Building. Gustav Klimt painted Wittgenstein's sister for her wedding portrait, and Johannes Brahms and Gustav Mahler gave regular concerts in the family's numerous music rooms." Karl, though, aimed "to turn his sons into captains of industry; they were not sent to school lest they acquire bad habits, but were educated at home to prepare them for work in Karl's industrial empire. Three of the five brothers would later commit suicide. After the deaths of Hans and Rudi, Karl relented, and allowed Paul and Ludwig to be sent to school [though] it was too late for Wittgenstein to pass his exams for the more academic Gymnasium and only barely managed after extra tutoring to pass the exam for the more technically oriented Realschule."

As an interesting historical anecdote, Adolf Hitler was at that same school and although the two were born only six days apart, Wittgenstein skipped a year and Hitler was held back one so even though they almost certainly met each other, there's no indication they influenced one another. However, something must have been in the air there as later in life, Wittgenstein was described by a member of the Vienna Circle thusly:

"His point of view and his attitude toward people and problems, even theoretical problems, were much more similar to those of a creative artist than to those of a scientist; one might almost say, similar to those of a religious prophet or a seer... When finally, sometimes after a prolonged arduous effort, his answers came forth, his statement stood before us like a newly created piece of art or a divine revelation ... the impression he made on us was as if insight came to him as through divine inspiration, so that we could not help feeling that any sober rational comment of analysis of it would be a profanation."

This attitude helps explain another of Wittgenstein's quotes, which would otherwise seem out of place for the 20th century's premier logician.

So in the end when one is doing philosophy one gets to the point where one would like just to emit an inarticulate sound.

To this, I can only say....grrrrrgggghhhh.

But, in fact, I can say a bit more too. Because as Wittgenstein also said:

A philosopher who is not taking part in discussions is like a boxer who never goes into the ring.

To convince someone of the truth, it is not enough to state it, but rather one must find the path from error to truth.

Philosophical problems can be compared to locks on safes, which can be opened by dialing a certain word or number, so that no force can open the door until just this word has been hit upon, and once it is hit upon any child can open it.

So, if you can, please enter the ring with me. Help me find my path from error to truth. And let me know your thoughts about what combination I'm trying that isn't working for you. Because I do want philosophy to be alive again and more than just an act of clarification.