And there is where I had some real questions and potential differences with Andy. To try and resolve them, I followed up on several of the footnotes from the book after I finished reading it. In particular, I found Andy’s 1997 paper “Regress and the Doctrine of Epistemic Original Sin” to be very illuminating. Still, I had more questions, so I had an extensive back and forth with Andy over email. And I’ve thought about that exchange continually for a few months now while I’ve carried on with my other epistemology research. I’ll leave the details of my private exchange private, but I think I’ve hit upon some good ways to resolve any issues we left outstanding. (At least to my mind.)

A good place to start is with Andy’s humble pleas about his daring proposal for a “New Socratic model of reasonable belief.”

- (p.319) My philosopher friends will pick at it. That’s okay: it’s more a heuristic than a fully worked-out theory, and I welcome efforts to refine it.

- (p.342) By all means, explore the space of possible challenges, and give voice to those I’ve missed. Delve deeper than I have, and bring overlooked challenges to my attention. But don’t make sport of hoisting my petard; be a friend, and lead me away before it blows. Better yet, guide us all to a better alternative.

Those are wonderful words that should really be in the preface of all works of philosophy. (I’ve said something very similar on the Purpose page of my website.) And in that spirit, let me use this post to try to lay out a few of my personal alternatives for Mental Immunity. I’ll leave it to posterity to decide if these are “better” or not. In summary, I have found that there is one main concept that separates Andy and I, and one supporting concept that needs more consideration. Otherwise, we’re practically perfectly aligned.

First, the supporting concept. In order to claim that one infectious idea is good while another mind-parasite is bad, you really need a way to define good and bad. You could just go the amoral, instrumental route and say you’re only concerned with whether an idea is good or bad for its goal. For example, most of us would say it’s a morally bad idea to fly planes into an office tower, yet we may readily admit that it was a good tactic relative to the terrorists’ beliefs. That would be one way to deal with the issue of value judgments—by basically ducking them. However, Andy wants to do more than that. He wants to be able to judge which ideas are really good and which ones are really bad. And that requires an ethical judgment. What does he use for his criteria? In his discussion with Jamie Woodhouse at Sentientism, Andy said the fact-value distinction can be crystalised by one simple sentence — “Well-being matters.” — and this will be the topic of his next book. That’s great to hear about another book because this needs a lot of consideration. Well-being is a highly contested idea with a long history of philosophical attempts to define it, so it seems to me that Andy has merely kicked the can down the road until he can deal with that definition. Fine. In my recent paper about rebuilding the harm principle, I defined well-being as “that which makes the survival of life more robust” (with harm moving in the opposite direction towards fragility, death, and extinction). I believe this is the long-sought objective grounding for ethics, which I’m happy to discuss at another time. For now, let me just insert this into Andy’s work wherever I think he needs it and then I find much closer alignment with it.

Now for the main concept keeping us apart. Truth. In my work, I say we should drop all claims for it, whereas Andy is happy to keep using that word throughout his work. For a discussion about epistemology, that sure sounds like a big deal! As with so much in philosophy, however, this boils down to definitions. In the excellent Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on truth, there are several theories of truth that are considered — the Correspondence Theory, the Semantic Theory, the Deflationary Theory, the Coherence Theory, and the Pragmatic Theory. There’s no need to wade into that discussion right now since these deal with the ontology of truth—what is it?—whereas we’re presently concerned with its epistemology—can we know truth? For me, that answer is a resounding no, because, as the IEP article lays out, "most philosophers add the further constraint that a proposition never changes its truth-value in space or time.” In other words, the word truth in philosophy means an eternal and unchanging fact. But because we live in an evolving world where we cannot know what revelations the future will bring, that rules out certifying any proposition as true. And as the IEP article says in its section about knowledge, “For generations, discussions of truth have been bedevilled by the question, ‘How could a proposition be true unless we know it to be true?’” According to that a strict requirement, they cannot.

To drive this point home, I discovered a striking fact in Julian Baggini’s recent book How the World Thinks: A Global History of Philosophy. While discussing the recent problems with Russia and its campaigns of misinformation, Baggini noted on p.355 that, “Even the Russian language helps to maintain the elasticity of truth, for which it has two words. Istina is natural truth, the truth of the universe, and is immutable. Pravda, in contrast, describes the human world and is a human construction.” I studied Russian for a few years, and there is some debate about these definitions, but wouldn’t it be helpful here for philosophers to actually make this distinction and nominate a word for the specific meaning of istina in the sense given here? As it stands, philosophers mix these up all the time and it creates real unsolvable problems. For example, there is this passage from elsewhere in Baggini’s book when he is talking about the pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce:

- (Baggini, pp.84-5) Given that most convergence on truth is in a hypothetical future, in practice this means what we now call truth is somewhat provisional and relative. “We have to live today by what truth we can get today, and be ready tomorrow to call it falsehood,” wrote Peirce. The worry is that if we take this seriously, we are left with a dangerous relativism in which anyone can claim as true whatever they happen to find useful. Truth becomes a matter of expediency and it is then impossible to dispute the truth claims of others, no matter how wild.

Such wild relativism is exactly what Andy wants to fight in Mental Immunity, and he comes up with a novel way to defend his own truth claims. But I think a clearer definition of the word truth, and an avoidance of any connotation of istina, would help to finish the fight even better. Unfortunately, the word truth doesn’t even make it into Andy’s otherwise very extensive 17-page index. The deeper concept of truth is just not something he’s considering here.

So, what’s the right approach for defining truth? Do we deflate truth to mean pravda so it’s compatible with reality, or do we insist that it is istina, and then eliminate it from our usage as an illusion that’s incompatible with reality? This is the kind of choice that Dan Dennett has faced with both consciousness and free will. For the former, as it is widely used, Dan says consciousness is an illusion and we can eliminate it. For the latter, he considers the concept of free will to be so important that we need to deflate it into “the free will worth wanting” in order to keep it in use. Dan spelled that out explicitly in his paper “Some Observations on the Psychology of Thinking About Free Will” while he reacted to Daniel Wegner’s book The Illusion of Conscious Will. He wrote:

- I saw Wegner as the killjoy scientist who shows that Cupid doesn't shoot arrows and then entitles his book The Illusion of Romantic Love. Wegner does go on to soften the blow by arguing that "conscious will may be an illusion, but responsible, moral action is quite real" (p. 224). Our disagreement was really a matter of expository tactics, not theory. Should one insist that free, conscious will is real without being magic, without being what people traditionally thought it was (my line)? Or should one concede that traditional free will is an illusion—but not to worry: Life still has meaning and people can and should be responsible (Wegner's line)? The answer to this question is still not obvious.

Similarly, should the word truth only be used for the unerring eternal truths of what really, truly, actually exists (my line) or should the word truth be used for what we think is correct right now while remaining open to revising it later (Andy’s line)? Based on Dan Dennett’s two examples, the correct answer may depend upon the situation. Both choices have their advantages and drawbacks. But to me, religious believers are going to hang on to their usage of the word "true" as unerring and eternal. So, we who see that that is not tenable need to be the ones to avoid its usage. We have plenty of other options at our disposal — accurate, correct, verifiable, factual — and this gives us plenty of opportunities to be loud about admitting we simply can never get to the unerring certainty of truth. And that instils the humility necessary to ensure continued inquiry and dialogue, which is so important for building shared consensus.

I didn’t arrive at this explicit conclusion until after my email exchange with Andy, but I think it fits in with the two big fundamental positions that he and I did agree upon: 1) knowledge is provisional; but 2) we still can establish reasonable beliefs. It remains to be seen whether my "truth" is the right one to insist upon.

Now that I’ve laid out my own definitions for truth and goodness, I can now go over the last part of Andy’s book and interpret it in a way that I think is satisfying to us both and builds upon our two foundations of agreement. As before, I'm not going to provide a formal review of this book. I'll just share some selected excerpts that I jotted down and insert a few of my own thoughts and interpretations where necessary. All page numbers are from the 2021 first edition from HarperCollins.

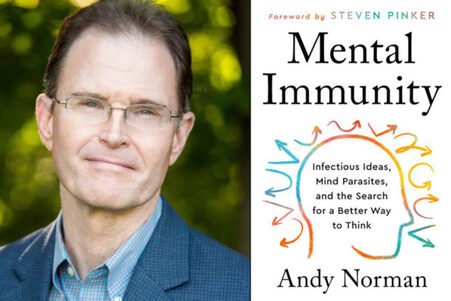

Mental Immunity by Andy Norman

- (p.258) When I speak of a “better” understanding of reason’s requirements, I mean one that is clear, explicit, vetted, defensible, well functioning, and shared. What makes these the right qualities to focus on? Well, look at the way reasoning works, and think about ways to improve that functioning. Do this, and it quickly becomes apparent what “better” ought to mean in this context.

Andy starts with this bare instrumental usage of the term better. Unfortunately, terrorists could probably use these criteria to say they are thinking well too. They provide clear, explicit, defensible, shared, and well functioning arguments for how to apply sharia law for the salvation of human souls. We need some more criteria if we want to judge their beliefs as mind-parasites. I think my definitions of good and harm make this very clear they fall in the bad category.

- (p.262) When [Socrates] wanted to determine the worthiness of a claim, he’d test it with questions and see how it fared. The implied standard in such an approach is this: judgments that can survive critical questioning might merit acceptance, but those that can’t don’t.

I love to see the use of the word “survive” in these descriptions of epistemology. That's a key term in evolution and it fits right in with my JBS theory of knowledge.

- (p.268) While useful for combatting confused and mistaken judgments, the Socratic picture is less than ideal for building common knowledge. Actually, this understates the problem. The Socratic conception turns out to be profoundly corrosive of the very possibility of positive knowledge.

Andy thinks this is a problem, but to me this is okay because positive knowledge is not possible. As I wrote in my review of Why Trust Science? by Naomi Oreskes, “Oreskes jumps into this story…with Auguste Comte—the father of positivism—and what she calls ‘The Dream of Positive Knowledge.’ If anything could be trusted, it would be a scientific finding that had been absolutely positively proven to be true. Unfortunately, as Oreskes makes clear with her retelling of the history of science, such dreams have proven fruitless.” We have to accept this situation with humility and move on with the best we can get…which can still be very good.

- (pp.276-81) 300 BC to 1500 CE … During this extended period, three basic epistemologies gained and lost influence: Aristotle’s, that of the Academic skeptics, and that of Christian philosophers. Each made an uneasy accommodation to the Platonic picture of reason. Each developed an influential standard of reasonable belief—one that gave rise to a distinctive set of reason-giving practices. And each of these epistemologies—initially a “solution” to the quandary of basic belief—went on to shape Western civilization in ways both subtle and profound. … Aristotle’s answer was clever but evasive: our apprehension of first principles is “immediate”—that is, direct and unmediated. In other words, we simply behold them and know them to be true. We know this answer to be problematic. … Aristotle was playing a kind of shell game, hiding his lack of a deep solution to the regress problem. … According to leading scholars, Academy philosophers employed a skeptical strategy that “…attempted to show that all claims are groundless.” “For over two hundred years,” writes one of them, “’Why do you believe that?’ became the leading question in philosophical discussion. ‘You can have no reason to believe that’ became the skeptical refrain.” … We’re talking now about a radical skepticism, one that obliterates the distinction between reasonable and unreasonable belief, thereby undermining healthy mental immune function. … Epistemology had painted itself into a corner and made itself all but irrelevant to practical thinkers. … This led early Christian thinkers to try a different tack…we must accept some things on faith. In the same way that God can halt the regress of causes (by being the Creator, or Prime Mover), faith in God can halt the regress of reasons. Just as God provides the true basis for existence, faith provides the true basis for knowledge. This faith-based understanding…helped entrench an orthodoxy that discouraged challenges to church teaching. It excused stubbornly dogmatic thinking and compromised mental immune systems across Europe. … For centuries thereafter, academic skepticism made it hard for the well educated to have the courage of their convictions. [An] option…to try and steer a middle path between skepticism and dogmatism…is to argue that certain beliefs really are properly and objectively basic, or foundational, for us all. … When pressed…foundationalists have tended to wave their hands and employ techniques of distraction. This has diminished rationalism and prevented it from becoming an influential movement.

This is an incredibly helpful summary of the historical problems and developments within epistemology. These are the efforts that Andy is trying to reconcile and surpass. (As am I.) Framing this issue as the need to find the middle path between skepticism and dogmatism is extremely clarifying.

- (p.283) If we hope to establish anything “firm and lasting in the sciences,” Descartes wrote, we must first raze the foundations of received opinion, and build all of knowledge afresh upon beliefs that cannot be doubted.

This, of course, is an impossible goal now that we see how life arose in the middle of the evolution of the universe, which leaves us in a position where we cannot actually gain the type of knowledge “that cannot be doubted.” The cosmological revolutions that Darwin wrought need to trickle down to our epistemology as well.

- (p.283) Descartes’ architectural metaphor gave modern thinkers a convenient way to cast the central philosophical problem of the age: On what foundation does true knowledge rest? But it also did something more subtle and far-reaching—something that has, until now, escaped notice: it projected a gravitational field onto the space of reasons.

This is a very interesting observation from Andy! He’s right that knowledge is spoken about as having gravity and requiring a foundation. But actually, it is only ever free-floating, using sets of hypotheses that we continue to test and refine. There is just no “bedrock of truth” down there.

- (p.286) In sum, the Platonic picture not only survived the Enlightenment, it traversed it in grand style. It was borne along by the foundations metaphor and its attendant assumption of epistemic gravity. It helped generate one of the defining problems of the age, a difficulty that modern philosophers ultimately failed to solve. Only now can we see why: the Platonic picture has long created cognitive immune problems. It leads us down the garden path to an extreme and impractical skepticism, which again and again compels reactionaries to embrace a ferocious dogmatism. In this way, it renders some mental immune systems hyperactive, and others underactive.

This is a good summary of Andy’s diagnosis of the problem with epistemology. The framework he set up earlier—as needing to thread the needle between skepticism and dogmatism—lines up perfectly with a cognitive immune system that is dysfunctional at either end of the spectrum. The middle path is the way forward. I would only add that acknowledging the merits of skepticism doesn’t necessarily lead all the way to extreme and impractical skepticism. I think it keeps one from ever contemplating the temptations of dogmatism. Therefore, my methods of defining knowledge as justified beliefs surviving our best tests also results in a mental immune system that is neither underactive nor hyperactive.

- (p.288) Empiricism, it turns out, is more problematic than it appears. For one thing, it’s often appropriate to question perceptual judgments. … More generally, our senses can deceive us. … Perceptual judgments can, but need not, bring reasoning to a close. How are we to know when they do and when they don’t? Second, perceptual beliefs seem an inadequate basis for the full breadth of our knowledge—a corpus that includes not just matters of empirical fact, but also mathematical truths (e.g. the Pythagorean theorem), counterfactuals (“If average global temperatures rise two degrees, sea levels will rise”), causal laws (“Smoking causes cancer”), things about the near future (“I will go to the store tomorrow”), ethical knowledge (“Honesty is the best policy”), basic things about other people’s minds (“Joe is happy”), and so on. Indeed, it is exceedingly difficult to give a convincing account of how causal knowledge, knowledge of the future, knowledge of right and wrong, and knowledge of other minds are grounded in empirical evidence.

I actually found this criticism of empiricism difficult to follow. Where else can knowledge come from but our senses? There isn’t another natural possibility. I personally found it easy to link these examples of the full breadth of our knowledge to perceptual beliefs. Even logical rules and mathematical truths are shown to work over and over again by empirical evidence. If gods intervened regularly with supernatural interruptions to reality, how would we ever develop theories about the laws of nature? Perhaps I’m missing something about the claims of empiricism, but I think it holds together.

- (pp.291-2) The ethic of belief that prevails across much of the world today is a variant of empiricism. It centers on the notion of evidence, so philosophers call it “evidentialism.” The core idea is simple: to be genuinely reasonable, a belief or claim must be backed by sufficient evidence. … (This is the same idea W.K. Clifford defended, so the Western tradition’s “Big 4” pictures of reasonable belief are, on my telling: the Socratic, the Platonic, the Humean, and the Cliffordian.) … Where did evidentialism come from? Empiricism, I think, matured into evidentialism. In a way, it’s just empiricism generalized.

This distinction was new to me, so maybe there is indeed some hair-splitting work to be done on definitions here.

- (p.294) Evidentialism entails the illegitimacy of beliefs not supported by sufficient evidence. It’s not hard to imagine this standard working well to sort responsible from irresponsible claims about what is. Indeed, it has a long and distinguished track record of doing just that. Unfortunately, we can’t say the same about its treatment of claims about what ought to be. In fact, it’s quite hard to see how evidence alone can license any claim about right or wrong, good or bad.

Actually, my paper on the bridge between is and ought would solve this. To me, the right way to derive oughts are by looking at how life must act in order to stay alive. That is the only context in which oughts make sense. There just aren't any oughts for rocks. Oughts only apply to living things. And we have gained all sorts of natural evidence for what promotes more and more robust survival for life (i.e. well-being).

- (pp.296-7) Reason can have nothing to say about our most basic ends and values. Our core ends and values, it seems, must be determined by something utterly nonrational: preferences, desire, faith, or the like.

This is a common position among philosophers who steer clear of Hume’s guillotine, but this is an example of where I might try to improve Andy’s arguments. First of all, I don’t know of anything that is utterly nonrational. That sounds like something supernatural to me. Reasons and emotions are not mutually exclusive things. I’m not a dualist about them. Instead, it’s clear that reasons and emotions are related to one another. They feed off one another in a bi-directional manner. There are reasons we feel emotions, and, as Hume said, reasons are the slave of the passions.

- (p.299) For some years, the philosopher Alvin Plantinga has been arguing that, in many cases, rational belief simply doesn’t require evidence. Or, for that matter, any supporting argument. … If arguments like this go unanswered, the evidentialist ethos will eventually wither and die. Plantinga’s case, though, is presently gaining influence: it’s anthologized in popular introduction to philosophy textbooks, and is routinely taught to thousands of undergraduates.

WTF?! That sure is a sorry state of affairs for philosophy. And Andy is right to dedicate a book to fighting it.

- (p.301) Plantinga then points out (correctly, in my view) that “no one has yet developed and articulated…necessary and sufficient conditions for proper basicality.” His point, stripped of jargon, is simple: no one has yet spelled out what may properly be deployed as an unargued premise. Rationalists seem to owe us such an account, for they propose an argument-centred standard of rational permissibility. To function capably as rational beings, we need to know when it’s okay to treat a claim as admissible, yet not in need of further argument. Rationalists, though, have yet to provide such an account. … Can evidentialism be repaired? Can we resolve the quandary of basic belief, and revive the rationalist project? The answer, it turns out, is yes. But only if we make a clean break from the Platonic picture of reason.

That’s a bold claim! In my main post to date about knowledge, I said that a free-floating hypothesis that has yet to be disproven is the best we can do to start building our knowledge, and that has proven to be awfully good. But let’s see what Andy has in mind.

- (p.306) I took the Socratic standard and plugged in the concept of challenges. That yielded what we might call the “New Socratic standard" — The true test of a good idea is its ability to withstand challenges.

This is very good. I’d say it’s the equivalent of Oreskes’ description of science arriving at broad consensus after debates from all manner of people, but, as Andy has done, we can extend this from scientific knowledge to all of knowledge. That aligns very well with my own conception of knowledge as justified beliefs that are surviving.

- (pp.309-10) How do we know whether a given challenge arises? … The solution involves distinguishing two kinds of challenge. One kind seeks to invalidate a claim by presenting reasons against the claim at issue…I call them “onus-bearing” challenges. … The other sort of challenge is simpler. Sometimes, a challenger offers no reasons against but instead just asks the claimant to provide reasons for. … These simpler challenges are naked grounds for doubt, so I call them bare.

This is a key move for Andy in his attempt to stop the infinite regression of asking why, which otherwise leads to radical skepticism. It's a nice distinction to make about challenges to beliefs.

- (p.311) Entire schools of ancient philosophy managed to convince themselves that iterated bare challenges undermine all claims to knowledge. They became indiscriminate critics and lost the support of more pragmatic thinkers.

This may be an accurate representation of history, but I don’t think iterated bare challenges are the only way that skepticism arises. There are Descartes’ evil demons, sci-fi speculations that we are in the matrix, Baggini’s thought experiment about hypnotists, Arne Naess’s description of efforts to claim truth as “trying to blow a bag up from the inside,” or Fitch’s paradox of knowability which concludes that in order to know any truth you must know all truths (which we cannot). Andy claims in a footnote to have dealt with these objections in an earlier paper, but I could not find it. I believe that skepticism still holds for any claims of unarguable truth. And that's how I stop any moves towards dogmatism.

- (p.312) For example, “We should treat each other kindly” is by no stretch of the imagination a “fact present to the senses.” Nor is it a “fact present to memory.” (Most philosophers don’t even consider it a fact.) It’s plainly true, though, and those who assert it are under no obligation to prove the point.

This is representative of the kind of passages in Mental Immunity that I think could be strengthened by the two arguments I made in the beginning of this post about goodness and truth. First of all, it seems to me that we have lots of evidence from our senses that treating each other kindly leads to good outcomes. (Except when we are enabling bad behaviour and then we may need to be cruel to be kind.) So, this is where my supporting definition of good and harm can be put into play. Secondly, saying “it’s plainly true” does not make it so. To me, that sounds like Plantinga’s derided argument above that “rational belief simply doesn’t require evidence.” It’s also a signal to consider one of Dan Dennett’s 12 best tools for critical thinking —the ‘surely’ operator. As Dan says, “Not always, not even most of the time, but often the world ‘surely’ is as good as a blinking light in locating a weak point in the argument.” Surely, that applies in this case to the word "plainly" as well. Instead, I would have found it much better for Andy to simply avoid the use of the word true here, and say “treating each other kindly is a very well supported guide for most behaviour.”

- (p.317) There’s wisdom embedded in our pre-theoretical grasp of how reasoning should go, and any theory that hopes to strengthen mental immune systems must take account of it.

Andy doesn’t say what a “pre-theoretical grasp” is, but I can strengthen this by defining it as an innate valuation of survival. In my series on consciousness, I found the most basic level of consciousness to be built using “affect” or the valance of what is good or bad for life to remain alive. If that’s the wisdom Andy meant to tap into, then I can get on board with that.

- (p.319) I can now deliver the long-awaited mind vaccine: A belief is reasonable if it can withstand the challenges to it that genuinely arise.

This is intended to come as a big crescendo in the book. Presented here in such a short format, that may sound like question-begging. But when you dig into Andy’s book and learn what he really means for challenges to genuinely arise, this is essentially equivalent to my JBS theory that knowledge can only ever be justified beliefs that are currently surviving our best tests. Therefore, I’m happy to accept this end point for Andy’s argument. (Even if I quibble with how he got there.)

- (p.319) My philosopher friends will pick at it. That’s okay: it’s more a heuristic than a fully worked-out theory, and I welcome efforts to refine it.

I’m repeating this plea from above to put it in better context. When I first read this, it came across to me as a bit of a backtrack after an entire book filled with very bold claims. But yes, we can refine and strengthen this heuristic into a full theory. I would call that a theory of evolutionary epistemology, but that may just be me. No matter what we call it, Andy is on to something really big here.

- (pp.320-24) Where the Platonic picture nudges us into the “How do I validate this?” mindset of those prone to confirmation bias, the Socratic nudges us into the “What should we make of this?” mindset of the genuinely curious. … I see this as the model’s primary virtue [number one]. … The shift to a Socratic conception of reasonable belief, then, could mitigate, not just confirmation bias, but our proneness to ideological derangement. Let’s call this virtue 2. Virtue 3: The New Socratic model also implies that it’s not enough to mindlessly repeat the question “Why?” … Virtue 4: Notice next that the model directs us to consider both upstream and downstream implications. … Virtue 5: The model modulates mental immune response. In fact, it’s carefully designed to temper the impulse to question and criticize. … Virtue 6: The New Socratic Model promotes the growth mindset. For it primes us to learn from challenges. … Virtue 7: The model sanctions open-mindedness and scientific humility. For no matter how well you understand an issue—no matter how familiar you become with the challenges that arise in a domain—it’s always possible that a new challenge will arise and upset the applecart. … Virtue 8: The model also tells us what we must do to merit the courage of our convictions: become intimately familiar with the challenges to a claim that arise in a domain, and make sure that you can successfully address them. … Virtue 9: The model points to more effective ways to teach critical thinking. … Virtue 10: The model expands the purview of science. For the machinery of challenge-and-response allows us to treat any claim as a hypothesis.

Yes! I love all these virtues and agree they are present and helpful. I would even go so far as to call all of these changes, challenges, and growth to be evolutionary. : )

- (p.337) Still others object that the account deploys unexplained normative language, and thereby fails to fully explicate the concept.

I’m not surprised he’s faced these objections without a better explanation of what “better” actually means. I really think my evolutionary ethics can help here.

- (p.337) I insist that all claims are, and forever remain, open to onus-bearing challenges. We should never close our minds to the possibility that telling grounds for doubt might come along and invalidate a belief.

Agreed! And that’s why I drop truth from my criteria for knowledge. But I admit that entirely depends on your definition of truth.

- (pp.344-5) This story—the one our descendants might someday tell—might continue: In short order, our understanding coalesced into know-how. We learned to test claims with a certain kind of question: to seed minds with ideas that can withstand such questioning and weed minds of those that can’t. In effect, our forebears modified an ancient inoculant, produced a mind vaccine, and administered it widely. In this way, they curtailed the outbreaks of unreason that once terrorized our ancestors. They learned how to cultivate mental immune health, and transformed humanity’s prospects.

What an inspiring vision! Imagining a future with a healthy mental immune system modulating back and forth between more and less validated claims is much easier to see take hold in a society than any utopian visions for "perfecting man’s rationality." This really may prove to be a major conceptual breakthrough.

- (pp.346-50) Here, then, is a kind of “12-Step Program” to cognitive immune health. … Step 1: Play with ideas. … Step 2: Understand that minds are not passive knowledge receptacles. … Step 3: Get past the self-indulgent idea that you’re entitled to your opinions. … Step 4: Distinguish between good and bad faith. … Step 5: Give up the idea that learning is merely a matter of adding to the mind’s knowledge stockpile. … Step 6: New information is like a puzzle piece; you must find where it fits and how it connects. True wisdom requires you to clarify and order your thoughts. … Step 7: Don’t use “Who’s to say?” to cut short unsettling inquiries. … Step 8: Let go of the idea that value judgments can’t be objective. … Step 9: Treat challenges to your beliefs as opportunities rather than threats. … Step 10: Satisfy your need for belonging with a community of inquiry rather than a community of belief. … Step 11: Upgrade your understanding of reasonable belief. … Step 12: Don’t underestimate the value of ideas that have survived scrutiny.

Fabulous. Once again, I’d modify these ever so slightly with my additional points about truth and goodness, but I love to see the final emphasis being placed on ideas that survive scrutiny.

So, there you have it. As a nit-picking philosopher, I had a few issues with minor pieces of Andy’s arguments. It turns out that he, like every other philosopher so far, hasn’t solved all of the deepest problems in our field. But Andy still ends up in a very good place and he gives us incredibly helpful information along the way. As such, I highly recommend reading Mental Immunity on your own to get the full experience of actually improving your own mental hygiene.

And with that, it's time for me to get going on my own paper about evolutionary epistemology. I've got several projects in the pipeline right now so give me some time for that. In the meantime, have a great 2022. May you maintain or gain your full mental health.