- My Review of Just Deserts by Daniel Dennett and Gregg Caruso

- A Few Further Thoughts on Just Deserts

- Another Free Will Debate — Kaufman v. Harris (Part 1/2)

- Another Free Will Debate — Kaufman v. Harris (Part 2/2)

- Some Thoughts on Sam Harris' Final Thoughts on Free Will

- Summary of Freedom Evolves

If you read the 17,500 words in all those posts, you’ll have seen that there is already a large zone of agreement on this issue between hard incompatibilists like Caruso and Harris and compatibilists like Dennett, Kaufman, and myself. From my review of Just Deserts:

- Both are naturalists (JD p.171) who see no supernatural interference in the workings of the world. That leaves both [sides] accepting general determinism in the universe (JD p.33), which simply means all events and behaviors have prior causes. Therefore, the libertarian version of free will is out. Any hope that humans can generate an uncaused action is deemed a “non-starter” by Gregg (JD p.41) and “panicky metaphysics” by Dan (JD p.53). Nonetheless, both agree that “determinism does not prevent you from making choices” (JD p.36), and some of those choices are hotly debated because of “the importance of morality” (JD p.104). Laws are written to define which choices are criminal offenses. But both acknowledge that “criminal behavior is often the result of social determinants” (JD p.110) and “among human beings, many are extremely unlucky in their initial circumstances, to say nothing of the plights that befall them later in life” (JD p.111). Therefore “our current system of punishment is obscenely cruel and unjust” (JD p.113), and both [sides] share “concern for social justice and attention to the well-being of criminals” (JD p.131).

My previous six posts also led to this conclusion in my summary of Freedom Evolves:

- I basically found that I agreed with Dan that free will is not the magic libertarian thing that many ordinary folks believe in. But neither is it the fatalistic determinism that these folks see as the only other choice. Instead, there is something in between these extremes where more and more degrees of freedom have evolved into something that explains the phenomenology of what we experience, which Dan calls "the kind of free will worth wanting." [And] I think I have a few things to add to Dan's position on this, some details which make it clearer.

Another way to see the need for this compatibilist conclusion would be to look at a word cloud for all of the issues that get discussed during free will debates. I don’t have the time or resources to put lots of relevant texts into a computer program that would generate such a cloud showing the frequency with which each idea is used, but I did at least gather a list of many of the relevant concepts while I was going through the books and papers and interviews I’ve covered in this series. Please don’t read this entire list, but a quick scan is helpful:

- “In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation.” (Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species)

- “Neither Mayr nor Tinbergen provide a detailed account of how to integrate different areas of biological inquiry, but both provide enough discussion to make it clear that they have in mind a general practice that philosophers of science have characterized in some detail under the label ‘functional analysis’. The canonical account of this practice among philosophers of science is Robert Cummins’ (1975, 1983) account, according to which functional analysis consists in breaking down some capacity or disposition of interest into simpler dispositions or capacities, organized in a particular way.” (Conley)

- “Reduction, unlike analysis, ignores a system’s organization (1982), which Mayr characterizes as the interaction between components (Mayr 2004). Organization explains the emergence of new characteristics that could not be predicted from knowledge of the isolated components of a system, but analysis provides a middle ground between reductionism and holism (Mayr 1982). Mayr claims that ‘all problems of biology, particularly those relating to emergence, are ultimately problems of hierarchical organization’ (Mayr, 1982, p. 64).” (Conley)

So, for free will, we need a deep “functional analysis” where elements of that emerging property are listed out for separate consideration. In this way, nuances can be captured and lassoed into an evolving understanding of all the issues. Now, where have we seen a hierarchical organization of a complicated emergent biological process before?? Hmmm. This quote from one of Dan Dennett’s papers should help you remember:

- “It is no mere coincidence that the philosophical problems of consciousness and free will are, together, the most intensely debated and (to some thinkers) ineluctably mysterious phenomena of all. As the author of five books on consciousness, two books on free will, and dozens of articles on both, I can attest to the generalization that you cannot explain consciousness without tackling free will, and vice versa.”

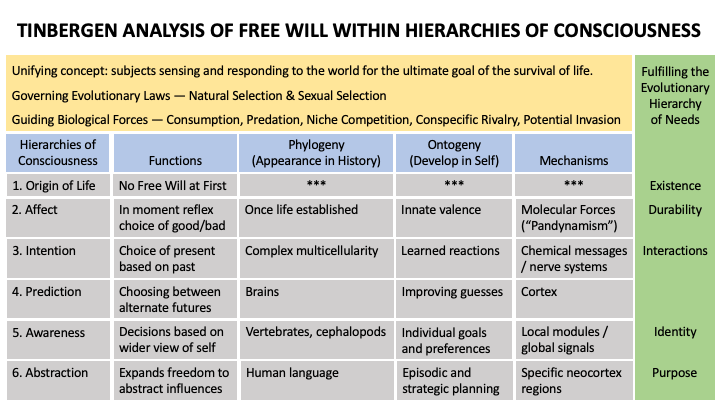

In my nearly finished series on consciousness (summarized here), I explained how a Tinbergen analysis is the proper way to explore and explain that complex emergent phenomenon. And since free will and consciousness are so tied together, a Tinbergen analysis is useful here too. This is the extra detail I would add to the free will debate beyond Dan Dennett’s generally excellent contributions that I have discussed so far. I hinted at this in my review of Just Deserts with the following passages:

- [M]ost philosophers [rely] on classical logic, which says A is A, not-A is not-A, and the law of the excluded middle says there is nothing else possible in between. Such rigid definitions work well in the precise worlds of mathematics and Newtonian physics, but not in the fuzzy world of biology. In that realm, the ethologist Nikolaas Tinbergen gave us his Four Questions which are now the generally accepted framework of analysis for all biological phenomena. To understand anything there, Tinbergen says you have to understand its function, mechanism, personal history (ontogeny), and evolutionary history (phylogeny). As a very simple example, philosophers could tie themselves in knots trying to define ‘a frog’ such that this or that characteristic is A or not-A, but it’s just so much clearer and more informative to include the stories of tadpole development and the slow historical diversion from salamanders. So, is free will more like a geometry proof or a frog?

- Tinbergen’s perspective gives us a few additional tricks. It isn’t luck that I grew up to be a person rather than a horse. Once I was conceived, the evolutionary history (phylogeny) that led up to me put a lot of constraints on my personal development (ontogeny). Luck may explain all the differences between me and every other person out there, but we needn’t worry about luck when describing all the things we have in common. There are hordes of characteristics that all humans share, but the one that is most important for this debate is our capacity to learn. The extreme neuroplasticity we have (a mechanism of free will) is what enables all but the most unfortunate humans to sense and respond to their environments (a function for free will) to the point where they slowly, slowly become a unique self.

For details on how I developed answers to Tinbergen’s four questions for consciousness, you need to see posts 18 (Tinbergen), 19 (Functions), 20 (Mechanisms), 21 (Ontogeny), and 22 (Phylogeny). Luckily, there’s no need to go into so much depth for free will now. Since the groundwork has been laid for consciousness, a quick sketch will suffice to show how free will folds very neatly into this view and then expands perfectly logically during the developments of consciousness. Essentially, it is clear that degrees of freedom only open up for living organisms, and they expand along as more and more levels of consciousness are developed. I don’t expect that to sound controversial, but the details are hopefully helpful to the discussion.

I think it’s easiest to grasp this table by focusing on the Functions column. Going from top to bottom, there is (1) no free will before the emergence of life. Once (2) life is established, the phenomenon of affect provides innate valences for making in the moment reflex choices between good or bad options for life. As (3) complex multicellularity develops mechanisms to learn and act on (unconscious at first) intentions, then life gains the freedom for choosing different actions in the present based on things it has learned in the past. Continuing on, the (4) development of brains enables modelling predictions of the world, which gives life freedom to choose between alternate futures. As all of these abilities lead to (5) the dawning of self-awareness, living organisms can begin to develop autobiographical narratives that inform choices over longer and longer time horizons depending on the quantity and quality of memories and predictions that have been developed. Finally, in the (6) realm of human language, we Homo sapiens have gained the freedom to be influenced by an infinite array of abstract representations. At this level, we can now see strategic planning of actions for decades of a life, which clearly drives the feelings of free will that exist in folk psychology.

This brief rundown does not begin to address all of the items in the word cloud shown above for the free will debate. But I’ve already touched on most or all of those in my other posts, so hopefully this final summary just provides a “hierarchical organisation of capacities” (a la Mayr via Conley above), which helps us see the slow step-by-step emergence of degrees of freedom that starts from absolutely nothing but eventually grows to the enormous range that philosophers have contemplated for millennia. Slapping a line on this chart and declaring “here lies free will” or “you must be taller than this degree of freedom in order to be free” would seem to be a very silly exercise. Yet that appears to be what people do when they declare “free will” to absolutely exist or not. Taking all of the facts together, however, by using a “functional analysis” that is typical of the philosophy of science, there is hopefully now a bit more grandeur in the evolutionary view of the emergence of free will. If this brief summary prompts any questions about specific items in my word cloud above, please ask them in the comment section below. Otherwise, I’ll consider myself free to pursue some other topics for now.