- The concept of free will touches nearly everything we care about: morality, law, politics, religion, public policy, intimate relationships, feelings of guilt and personal accomplishment. But the illusion of free will is itself an illusion. It is built on two things: the ability to choose otherwise and being the source of conscious awareness. But these are both wrong.

There are more things bound up in "free will" than just these two points. In particular, there's the question of avoiding external coercion, as well as the ability to carry out actions and plans that were made using conscious considerations. Both of those do a lot of work in building up feelings about the term free will. But even leaving those points aside for now, Sam's discussion of "the ability to choose otherwise" is a flawed repetition of ideas that have already been debunked. Dan Dennett knocked these down in his review of Sam's book, when he said:

"You can't assess any ability by 'replaying the tape.' ... This is as true of the abilities of automobiles as of people. Suppose I am driving along at 60 MPH and am asked if my car can also go 80 MPH. Yes, I reply, but not in precisely the same conditions; I have to press harder on the accelerator. In fact, I add, it can also go 40 MPH, but not with conditions precisely as they are. Replay the tape till eternity, and it will never go 40MPH in just these conditions."

So, looking backwards at decisions that were made just doesn't tell you everything you need to know about the ability to make decisions going forward. As for what Sam means about "being the source of conscious awareness", I'll have to hear more to understand his claims.

- There’s no place for you to stand outside of the causal structure of the universe.

Agreed. But my unique genetic and environmental history forms its own cause. We witness that from the inside as we act. That is consistent with the embodied view of consciousness. As I said in my review of Just Deserts, we may not have free will, as that makes it sound like free will is a possession that could be separated from our selves. But we are a will that has degrees of freedom.

- You aren’t a self. You’re not a subject in the middle of experience. You’re not on the riverbank watching the stream of consciousness. As a matter of experience, there is only the stream, and you are identical to it.

That’s right that we aren’t a homunculus watching the Cartesian theatre unspool before us in some ethereal mind space. But that stream that we are identical to is something. It exists. And I don’t see why we can’t call that an ever-changing, unique, and personal self.

- [Sam asks for you to choose a film. Any film.] We can’t see how those choices are made. If free will isn’t there, then it’s not anywhere.

Bollocks! This is just like the point I made in my last post about looking for a decisive moment in the random noise of choosing when to drink water. Sam is stacking the deck in his favor by asking for a random film choice, but there are no identifiable interior mechanisms to make random choices. If, instead, I asked you to choose the top 20 films of all time in terms of their return on investment, you would immediately be flooded with ideas on how to act to solve that problem. (And if you are JT Velikovsky, you will have already written a PhD thesis on this subject!) Where did those thoughts come from? From some mysterious darkness that we have no access to? No! They would come from learned experience that I myself have experienced, plus maybe some creativity at putting together bits of experiences that I haven’t thought about putting together before. This type of problem solving is one of the 13 types of cognition that we have evolved to have. And that feels very much like a self acting in its own self-interest.

- Everything is springing to mind. What could free will possibly refer to?

To the ability to hold onto a train of thought rather than pinging among these random upsurges?

- Letting go of free will is the only thing that cuts through the desire to retributively punish people.

Not so! The fact that you can’t change the past is another perfectly good reason to get rid of the desire to retributively punish people. From a consequentialist point of view, retributivism makes no sense.

- People ask, “if there’s no free will, then why are you trying to convince anyone of anything? … Your very effort to convince people that they don’t have free will is proof that you think they have it.” Again, this is confusion between determinism and fatalism. Reasoning is possible. Not because you are free to think however you want, but because you are not free. Reason makes slaves of us all. To be convinced by an argument is to be subjugated by it. It’s to be forced to believe it, regardless of your preferences.

Well, this certainly doesn’t track with the history of reasoning with people about their beliefs. Sam hasn’t responded to any of Dan Dennett’s very good arguments. Why not? Because people have their own unique personal histories, which drive their passions and their reasoning. These people are selves who act for their own self-determination.

- Not thinking about this clearly has consequences. In the United States, there are 13-year-olds serving life sentences in prison. Not because we have determined that they can’t be rehabilitated, but because some judge or jury felt that they truly deserved this punishment as retribution because they were the true independent cause of their actions.

This is an abhorrent shame and it definitely needs to be corrected. It’s possible that making the argument that “we don’t have free will” could actually open many people’s eyes to the problems with their retributivist thinking. But it’s also possible that such arguments close off many people’s minds because they think they definitely are autonomous agents, so free will skeptics must be out of touch with reality.

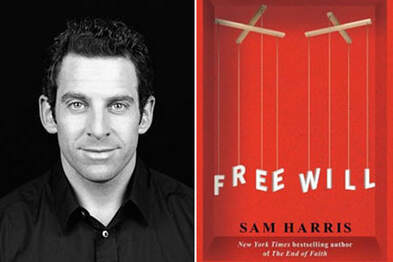

- At the moment, the only philosophically respectable way to defend free will is to endorse a view known as compatibilism and argue, in essence, that free will is compatible with the truth of determinism. Compatibilists like my friend the philosopher Dan Dennett generally claim that a person is free as long as he is free from any outer or inner compulsion that would prevent him from acting on his actual desires and intentions. So, if a man wants to commit murder, and does so because of this desire, then that’s all the free will you need. But from both a moral and scientific perspective, this seems to miss the point. Where is the freedom in doing what one wants, when one's very desires are the product of prior events that one had absolutely no hand in creating? From my point of view, compatibilism is just a way of saying that a puppet is free as long as he loves his strings.

Well, there are definitely strings from our evolutionary history. And natural selection has generally produced beings who love them. The ones that don’t tend to go extinct. In fact, in Just Deserts, Dan agrees with this and says, “I have adopted [this] sentence and reinterpreted it as indeed a pretty good definition of free will. … If you are lucky enough to be a responsible agent, you have an obligation to love your strings, protecting them from would-be puppeteers.”

- Compatibilists tend to push back here. They say even if our thoughts and actions are the products of unconscious causes, they are still our thoughts and actions. Anything that your brain does or decides, consciously or not, is something that you have done or decided. So, on this account, the fact that we can’t always be aware of the causes of our actions does not negate free will. Our unconscious neurophysiology is just as much us as our conscious thoughts are. But this seems like a bait and switch that trades a psychological fact, the subjective experience of being a conscious agent, for an abstract idea of ourselves as persons. The psychological truth is that most of us feel identical to or in control of a certain channel of information in our conscious minds, but we are wrong about this. The you that you take yourself to be isn’t in control of anything.

This is not a bait and switch by compatibilists. It’s a holistic understanding of our evolved and embodied selves. What’s wrong with that? Sam is the one who insists on fighting a straw man by merely picking on the worst kind of dualist, Cartesian, libertarian free will.

- Compatibilists try to save free will by asserting that you are more than your conscious self. You’re identical to the totality of what goes on inside your body, whether you are conscious of it or not. But you can’t honestly take credit for your unconscious mental life. In fact, you are making countless decisions at this moment with organs other than your brain, but you don’t feel responsible for these decisions. Are you producing red blood cells right now? If your body decided to stop doing this, you would be the victim of this change, not its cause. To say that you are responsible for everything that goes on inside your skin because it’s all “you” is to make a claim that bears absolutely no relationship to the feelings of agency and moral responsibility that have made the idea of free will a problem for philosophy in the first place.

And to treat red blood cell production the exact same way you treat conscious deliberation by human beings is (as I said in my last post) to sink to a level of dehumanization that is truly troubling. To say no one is responsible for anything that goes on inside your skin also bears absolutely no relationship to the feelings and facts that have made free will a problem for philosophy. Guess what. We aren't responsible for it all. And we aren't responsible for nothing. Let the hard work of philosophy begin.

Okay, that’s enough from Sam. He has helped me see more issues that need to be discussed, but it’s time for me to put them all on the table in my next and final post in this short series about free will.