Time to get back to the subject of free will. If you remember, I reviewed Just Deserts by Dan Dennett and Gregg Caruso for 3 Quarks Daily back in March. Then, I shared some passages that didn't make the final cut for that article. Next, while I was on this topic, I reviewed parts 1 and 2 of Scott Barry Kaufman's debate with Sam Harris about free will. And finally, I shared some thoughts on Sam Harris’ "Final Thoughts on Free Will" (that was the title of a podcast he posted in March). I finished that last post by saying:

"Okay, that’s enough from Sam. He has helped me see more issues that need to be discussed, but it’s time for me to put them all on the table in my next and final post in this short series about free will."

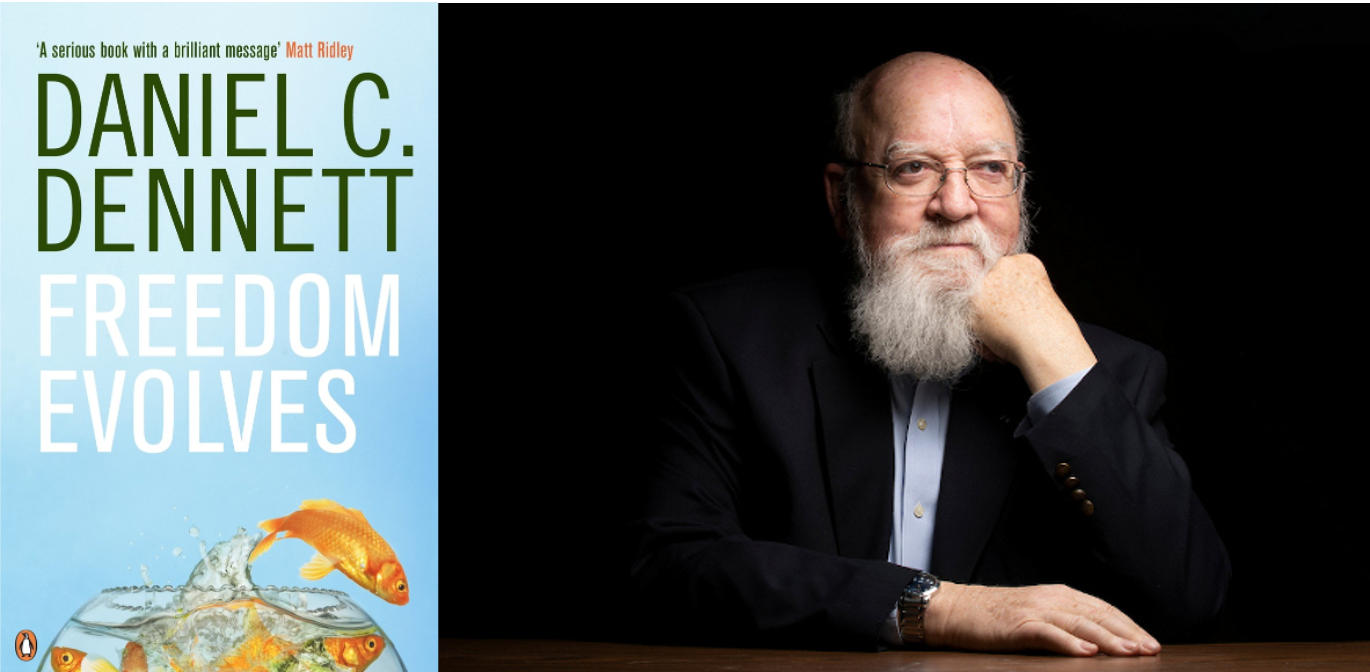

Well, as I began writing up that last post, I decided I really needed to go back and read Dan Dennett's full book from 2003, Freedom Evolves. I had read several of his papers on free will, and I'd read Just Deserts very closely (which Dan himself tweeted was his "latest and best defense" of his position on free will), and I basically found that I agreed with Dan that free will is not the magic libertarian thing that many ordinary folks believe in. But neither is it the fatalistic determinism that these folks see as the only other choice. Instead, there is something in between these extremes where more and more degrees of freedom have evolved into something that explains the phenomenology of what we experience, which Dan calls "the kind of free will worth wanting." I think I have a few things to add to Dan's position on this, some details which make it clearer, but I needed to go check Freedom Evolves to be sure. So, here are the main quotes (about free will) that I pulled from that book, along with just a few comments from me about them as well.

- p. 25 Determinism is the thesis that “there is at any instant exactly one physically possible future” (Van Inwagen 1983, p.3).

This is the succinct definition that Dan lays out at the beginning of the book which all naturalist / physicalist / materialist philosophers must recon with. This is really the crux of the free will issue. We humans feel that we have alternatives and that we make choices, but if there is only one physically possible future, then how real are these choices? If they are not real, then is free will really just an illusion?

- p. 59 [Dennett's imaginary foil Conrad says,] “Determined avoiding isn’t real avoiding because it doesn’t actually change the outcome.” [Dennett replies:] From what to what? The very idea of changing an outcome, common though it is, is incoherent—unless it means changing the anticipated outcome. ... The real outcome, the actual outcome, is whatever happens, and nothing can change that in a determined world—or in an undetermined world!

Dan is making the point here that we cannot change the past, and we cannot accurately anticipate the future. So, a determined world feels exactly the same as an undetermined world and we shouldn't get so worked up about which one we are in. But what struck me from this passage was the question of whose prediction are we talking about here? If no one is actually able to anticipate the future (more on this later), then the determined outcome is literally non-determined. Ahead of time, no one has actually determined it. Therefore, to worry about determinism is like worrying about someone who never reveals their guesses about the future but still annoyingly insists on repeating after the fact, "I knew you were going to do that. I knew you were going to do that."

- p. 75 Now that we have a clearer understanding of possible worlds, we can expose three major confusions about possibility and causation that have bedeviled the quest for an account of free will. First is the fear that determinism reduces our possibilities.

That's right. Determinism doesn't remove any of the possibilities that have been opened up by previous actions in the universe.

- p. 84 Philosophers who assert that under determinism S* “causes” or “explains” C miss the main point of causal inquiry, and this is the second major error. In fact, determinism is perfectly compatible with the notion that some events have no cause at all.

What Dan really means here is that some events have no known singular cause. He uses some examples like stock market fluctuations or legal cases where there are multiple attempted murderers to show that many events are simply overdetermined by several various things, which makes it impossible for us to say that any one thing caused the event.

- p. 88 Consider a man falling down an elevator shaft. Although he doesn’t know exactly which possible world he in fact occupies, he does know one thing: He is in a set of worlds all of which have him landing shortly at the bottom of the shaft. Gravity will see to that. Landing is, then, inevitable because it happens in every world consistent with what he knows. But perhaps dying is not inevitable. Perhaps in some of the worlds in which he lands headfirst or spread-eagled, say, but there may be worlds in which he lands in a toes-first crouch and lives. There is some elbow room.

That last sentence is, of course, a reference to Dan’s 1984 book Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting, which argues that our human-specific evolutionary history has carved out quite a lot of (elbow room) space for decisions to be made beyond the determinable knee-jerk reactions of simpler animals. This sounds great, but what doesn’t get emphasized from Dennett is that this perceived freedom is perhaps just due to ignorance. Could a super-intelligent being from another world scan the entire life history of the man in the falling elevator and know for sure that he will try a toes-first crouch because he once saw it in a movie as a teenager? Sure. I guess that’s possible. Does that matter to the choice the man is trying to make as he is falling towards his potential death? It shouldn’t, because that man cannot possibly know about it.

- p. 89 At last, we are ready to confront the third major error in thinking about determinism. Some thinkers have suggested that the truth of determinism might imply one or more of the following disheartening claims: All trends are permanent, character is by and large immutable, and it is unlikely that one will change one’s ways, one’s fortunes, or one’s basic nature in the future.

Well, those thinkers are just making an obvious error. A fixed future doesn’t mean an unchanging future. It just means that the changes are conceivably all knowable ahead of time. So, no one should have a fixed mindset vs. a growth mindset.

- p. 91 Every finite information-user has an epistemic horizon; it knows less than everything about the world it inhabits, and this unavoidable ignorance guarantees that it has a subjectively open future. Suspense is a necessary condition of life for any such agent.

Coming back to the point made above, Dan is showing how our ignorance about the future is always guaranteed.

- p. 91 Footnote 6 Laplace’s demon instantiates an interesting problem first pointed out by Turing, and discussed by Ryle (1949), Popper (1951), and McKay (1961). No information-processing system can have a complete description of itself—it’s Tristram Shandy’s problem of how to represent the representing of the representing of…the last little bits. So even Laplace’s demon has an epistemic horizon and, as a result, cannot predict its own actions the way it can predict the next state of the universe (which it must be outside).

So, in fact, that ignorance is a logical fact of every enclosed system. Nothing can get outside of everything it knows in order to truly know everything that might affect it. Therefore, not even Laplace’s demon could determine the future of its determined universe. And that kind of ignorance is vital to our feelings of freedom. This ends up being similar to something I said in my article “Mortality Doesn’t Make Us Free Either”:

“If there is any hope for the kind of spiritual freedom that Hägglund longs for, it could only be in the epistemological uncertainty that exists between certain mortality and certain immortality.”

- p. 92 Do fish have free will, then? Not in a morally important sense, but they do have control systems that make life-or-death “decisions,” which is at least a necessary condition for free will.

This hints at the evolutionary development of free will, which I intend to expand upon in my next post in a way that also aligns it with my summary of the development of consciousness. Furthermore, according to my view of evolutionary ethics, these “morally important” decisions are all life-or-death decisions. We humans are just able to consider longer time horizons and wider circles of moral concern. But the decisions we make are still moral or immoral if they lead to more robust or more fragile survival. (That’s my argument anyway. Lots of moralizers can be mistaken about what they think is moral or immoral.)

- p. 94 The question that interests me: Could Austin have made that very putt? And the answer to that question must be “no” in a deterministic world.

Correct. But no one knows which putts will be missed ahead of time, so we still plan and try to make them. And we learn from misses about what to do differently the next time we are in similar situations.

- p. 122 If you make yourself really small, you can externalize virtually everything. [See Footnote 6]

- p. 122 Footnote 6 This was probably the most important sentence in Elbow Room (Dennett 1984, p. 143), and I made the stupid mistake of putting it in parentheses. I’ve been correcting that mistake in my work ever since, drawing out the many implications of abandoning the idea of a punctate self.

Great point. This is exactly the trap that Sam Harris falls into when he refuses to see consciousness as embedded in our entire bodies with lots of unconscious processing. He has a very tiny (dualistic?) view of the self.

- p. 125 The idea that someone who has been tested by serious dilemmas of practical reasoning, who has wrestled with temptations and quandaries, is more likely to be “his own man” or “her own woman,” a more responsible moral agent than someone who has just floated happily along down life’s river taking things as they come, is an attractive and familiar point, but one that has largely eluded philosophers’ attention.

This is a great point that philosophers would not miss if they used the evolutionary framework of a Tinbergen analysis. The personal development of every individual (their ontogeny) is a vital part of the whole story of the development of free will.

- p. 127 We should quell our desire to draw lines. We don’t need to draw lines. We can live with the quite unshocking and unmysterious fact that, you see, there were all these gradual changes that accumulated over many millions of years and eventually produced undeniable mammals. Philosophers tend to take the idea of stopping a threatened infinite regress by identifying something that is—must be--the regress-stopper: the Prime Mammal, in this case. It often lands them in doctrines that wallow in mystery, or at least puzzlement, and, of course, it commits them to essentialism in most instances.

Great passage! This is drawn out much further in Dan’s paper about Darwinism and the overdue demise of essentialism.

- p. 135 Where is the misstep that excuses us from accepting the [incompatibilist’s] conclusion? We can now recognize that it commits the same error as the fallacious argument about the impossibility of mammals. Events in the distant past were indeed not “up to me,” but my choice now to Go or Stay is up to me because its “parents”—some events in the recent past, such as choices I have recently made—were up to me (because their “parents” were up to me), and so on, not to infinity, but far enough back to give my self enough spread in space and time so that there is a me for my decision to be up to! The reality of a moral me is no more put in doubt by the incompatibilist argument than is the reality of mammals.

This points out how incompatibilists attempt to rely on a version of the Sorites paradox to make their case, but that is an unsolved paradox for a reason! Imagine if I tried to start with the claim that I am responsible for my decisions, and then went back and back and back and back, claiming my responsibility continued to hold for each small step along the way, until eventually I took responsibility for the Big Bang. That is of course nuts. But that is essentially the exact same logic that incompatibilists are using on their side of the argument. They are just using it in the opposite direction. But if that trick doesn’t work for me, then it doesn’t work for them either. A new approach to the problem must be used. (Read the link above on the Sorites paradox to see a glimpse into an approach informed by evolutionary logic.)

- p. 223 Love is quite real, and so is falling in love. It just isn’t what people used to think it is. It’s just as good—maybe even better. True love doesn’t involve any flying gods. The issue of free will is like this. If you are one of those who think that free will is only really free will if it springs from an immaterial soul that hovers happily in your brain, shooting arrows of decision into your motor cortex, then, given what you mean by free will, my view is that there is no free will at all. If, on the other hand, you think free will might be morally important without being supernatural, then my view is that free will is indeed real, but just not quite what you probably thought it was.

This is an excellent synopsis of Dan’s argument. And it is basically consistent with his strategy for consciousness too. He says folk notions of consciousness are an illusion, just as folk notions of free will are an illusion. I believe he’s right that our definitions of these terms must evolve.

- p. 223 In my book Brainstorms, one of the questions discussed was whether such things as beliefs and pains were “real,” so I made up a little fable about people who speak a language in which they talk about being beset by “fatigues” where you and I would talk about being tired, exhausted. When we arrive on the scene with our sophisticated science, they ask us which of the little things in the bloodstream are the fatigues. We resist the question, which leads them to ask, in disbelief: “Are you denying that fatigues are real?” Given their tradition, this is an awkward question for us to answer, calling for diplomacy (not metaphysics).

This is a great example of the confusion that arises when Western languages use too many nouns. As I said in my review of Just Deserts, “We may not have free will, but we are a will with an infinite degree of freedom (subject to certain restrictions).” It may help somewhat to consider this issue as the act of a verb.

- p. 225 I claim that the varieties of free will I am defending are worth wanting precisely because they play all the valuable roles free will has been traditionally invoked to play. But I cannot deny that the tradition also assigns properties to free will that my varieties lack. So much the worse for tradition, say I.

Yep! The tradition must evolve.

- p. 237 The conclusion Libet and others should draw is that the 300-millisecond “gap” has not been demonstrated at all. After all, we know that in normal circumstances the brain begins its discriminative and evaluative work as soon as stimuli are received, and works on many concurrent projects at once, enabling us to respond intelligently just in time for many deadlines, without having to stack them up in a queue waiting to get through the turnstile of consciousness before evaluation begins.

Yep again! I was very glad to see this as I independently arrived at the same conclusion in my post about Libet. Good evolutionary thinking leads to the same places.

- p. 238-9 Conscious decision-making takes time. If you have to make a series of conscious decisions, you’d better budget half a second, roughly, for each one, and if you need to control things faster than that, you’ll have to compile your decision-making into a device that can leave out much of the processing that goes into a stand-alone conscious decision.

I thought this was an interesting precursor to Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- p. 243 As David Hume pointed out so vigorously several centuries ago, you can’t perceive causation. You can’t see it when it happens outside, and you can’t introspect it when it happens inside.

Excellent observation.

- p. 273 A proper human self is the largely unwitting creation of an interpersonal design process in which we encourage small children to become communicators and, in particular, to join our practice of asking for and giving reasons, and then reasoning about what to do and why.

This is a nice point to make about our ontogeny. Morality concerns others. It is built by them too. We could not develop selves or morality in isolation.

- p. 279 The hard determinists say that our world would be a better place if we could somehow talk ourselves out of feeling guilty when we cause harm and angry when harm is done to us. But it isn’t clear that any feasible “cure” along these lines wouldn’t be worse than the “disease.” Anger and guilt have their rationales, and they are deeply embedded in our psychology.

My analysis of what causes our emotions adds a lot of details to clarify this. Emotions (when they are working properly) do arise from reasons and we would be wise to recognize and hold on to the good reasons while discarding any poorly driven emotional responses. Properly aimed anger and guilt help shape individuals and societies to act towards more robust survival. Determinists think we can eliminate these and other emotions tied to notions of free will, but it is only the mistaken supernatural beliefs that need to go.

- p. 287 The self is a system that is given responsibility, over time, so that it can reliably be there to take responsibility, so that there is somebody home to answer when questions of accountability arise. Kane and the others are right to look for a place where the buck stops.

This is a nice description of how free will and moral responsibility are socially constructed in a bi-directional manner.

- p. 290 We now uncontroversially exculpate or mitigate in many cases that our ancestors would have dealt with much more harshly. Is this progress or are we all going soft on sin? To the fearful, this revision looks like erosion, and to the hopeful it looks like growing enlightenment, but there is also a neutral perspective from which to view the process. It looks to an evolutionist like a rolling equilibrium, never quiet for long, the relatively stable outcome of a series of innovations and counter-innovations, adjustments and meta-adjustments, an arms race that generates at least one sort of progress: growing self-knowledge, growing sophistication about who we are and what we are, and what we can and cannot do.

Yes! This makes for a good summary of the evolutionary steps that both free will and our understanding of it take. Next time, I’ll do my best to help grow that knowledge and sophistication just a tiny bit further.