For a little over two years, I’ve been heavily involved with an online community run by the non-profit organization ProSocial World. That’s where I led the creation and day-to-day running of the Evolutionary Philosophy Circle and I was also asked to be on the Stewardship Circle (a kind of advisory board) for the ProSocial Commons in general, which hosts lots of events and oversees the platform that is used by many other prosocial groups. These have all been run while focusing on two intellectual principles—Elinor Ostrom’s Nobel prizewinning research on the core design principles of groups that oversee common resources, and the scientifically validated Acceptance and Commitment Therapy used to foster psychological flexibility in individuals and groups. It’s been a fascinating and highly educational experience!

But….this has all been led by evolutionary biologists and psychologists who don’t have a strong track record or focus on building businesses. As such, the growing pains we’ve experienced would probably not surprise any entrepreneur. Recently, I started looking around for other examples of community building organizations to see what we could learn from them and the pop-up ad in the picture above splashed onto my screen. It’s from Gina Bianchini, who is the CEO and founder of Mighty Networks, which is currently “trusted by 900,000+ creators, entrepreneurs, and brands.” Bianchini grew up in Cupertino, California, graduated with honors from Stanford University, started her career in the High Technology Group at Goldman Sachs, and received her MBA from Stanford Business School. The front page of the Mighty website asks, “What makes Mighty different? Our obsession with member engagement.” This sounded exactly like the kind of business experience that ProSocial World needs, so I ordered my free copy of Purpose: Design a Community & Change Your Life and I raced through it when it arrived, dog-earing many of the pages and taking lots of notes.

Since Bianchini is giving her book away for free, I feel safe in sharing so many good details from it. But really, if you have any interest in joining or creating a community group, and these details pique your interest in the slightest, get yourself a copy and spend a bit more time with these ideas. (I think of this blog post as the “snack”. Go get the book for the full “meal”.)

First, what’s in it? Here is the table of contents. This is all covered in bite-size chunks totaling just under 180 pages. You can easily read it in a day or two.

Preface

Part I: Find Your Purpose

1. How I Found My Purpose, and You Can Too

2. Purpose in Modern Life

3. Purpose in Practice

4. Your Future Story

5. Your Future Story is Your New North Star

Part II: Turn Your Purpose into Action

6. From Hero to Host

7. Your First Host Skill: The Power of a Great Question

Interlude: Where We Go From Here—Onward to Digital

Part III: Take Your Purpose Digital

8. The Power of Digital is Creating Culture at Scale

9. What to Expect When You Create a Digital Community

10. Who Needs Your Community the Most Right Now?

11. From Purpose to Big Purpose

12. Launch Your Community to Your Ideal Members with Community DesignTM

13. Your First Digital Members Come from Your Core Community

14. Take Your Members on Quests

15. Conclusion

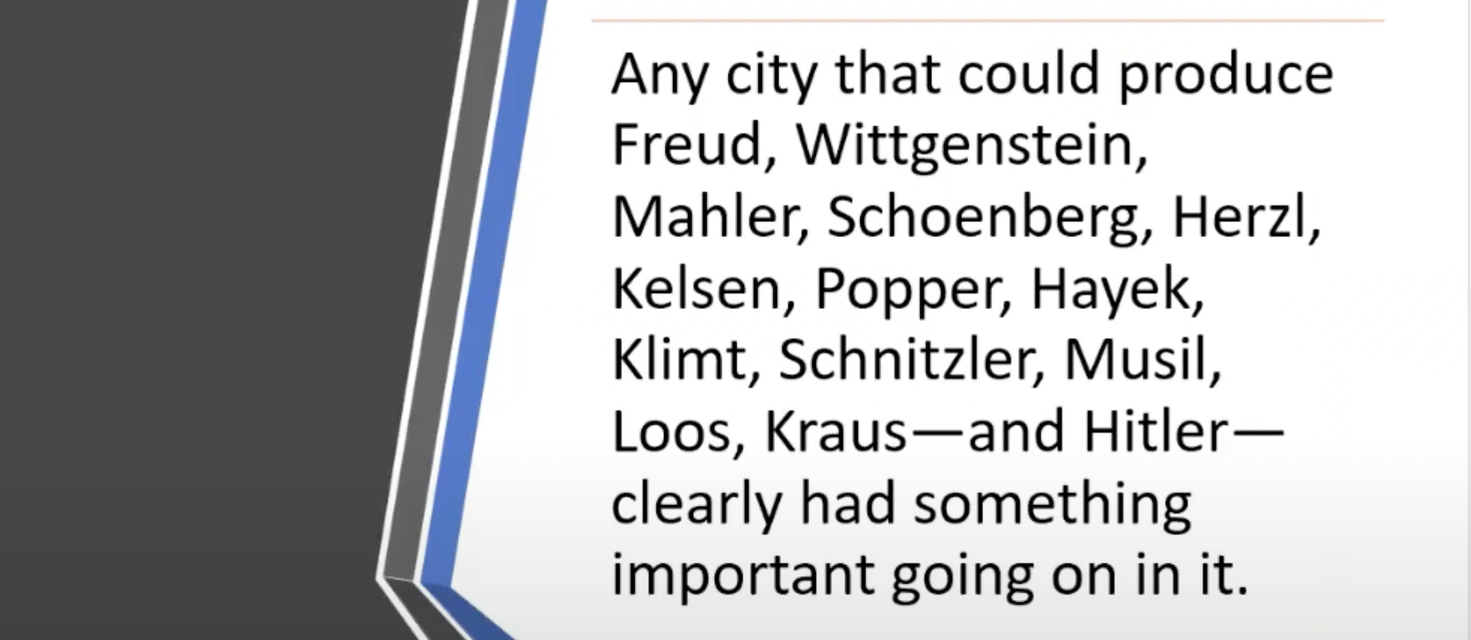

Because of the timing of her upbringing in Silicon Valley, Bianchini’s interests led her to cross paths with a lot of the major players in the development of the internet. I found her comments about “social media” particularly enlightening.

- (p.24) Facebook was defining what social networks would become. First, they quietly and subtly shifted from calling it a social network to referring to it as social media. While to the outside world this wasn’t a major shift, I saw it as ominous.

- (p.24) The true value of Facebook and any social network is the connections made between people. The power of social networks, then, is they become more useful to everyone with each new person who joins and contributes.

- (p.24) Facebook would keep the network hidden and replace it with social media operated mainly in a single “newsfeed” and controlled by a complex algorithm.

- (p.24) In Facebook groups, an administrator could no longer message the members of their groups, control which posts their members would see in their feed, or prevent the marketing of other groups to their members.

- (p.24) Where groups or interest pages once enjoyed in their own space, now individual group posts were stripped of all context and shown next to every other post surfaced by the algorithm. In the name of removing friction, Facebook was setting up a single (and fragile) “monoculture”. … The system was much more easily manipulated by outrage and extreme emotion.

Bianchini was keeping close tabs on all this as the co-founder of Ning.

- (p.26) I pictured a different future, one where creators owned their own communities and could design the cultures, experiences, and relationships they sparked between their own members.

- (p.26) There was content to inspire and influence, but unlike social media that stopped at content, a creator or brand could do something more powerful with cultural software. They could use native courses to educate and apply, enabling people to go deeper around new ideas and begin to apply new frameworks to their lives. Commerce was there not just to ensure creators, entrepreneurs, or brands could charge for access but to help members focus and prioritize. It turns out, people pay attention to what they pay for. Therefore, the fastest way to build a loyal, tightly knit set of early adopters or brand loyalists was by making the community paid, charging for events, or offering paid course communities. Perhaps counterintuitively, the easiest way to move people off social media was to charge for access to people, conversations, writings, and experiences outside of it.

Now that the world has experienced all the decay and harm from Facebook’s model of social media, doesn’t this “cultural software” sound like a breath of fresh air? It can’t grow as big or come to dominate the world, but that’s kinda the point. And it’s the right way to build robust diversity. Fragile monocultures all go extinct much more easily.

But how do we build all of these online communities? After working on thousands of them, Bianchini has developed some best practices.

- (p.27) People who hosted successful networks approached their communities with an openness and their own curiosity. They embraced a “growth mindset”. They also took specific steps to make their communities happen in pursuit of a shared purpose. … I called it Community DesignTM.

- (p.27) Our promise with Community DesignTM? Create a community so valuable you can charge for it, and so well-designed it essentially runs itself.

- (p.28) A course didn’t need to be sterile videos and guides alone. Rather, I could treat it as a living, breathing, and forgiving community of fellow travelers, equally interested in how to unlock the power and potential of bringing people together with intention.

- (p.28) The most successful communities online and in the real world started with a clear purpose. They not only had a clear intention, but the way they stated that intention followed a specific formula that worked time and time again to draw the right people to a new idea, join a community, or sign up for a course or membership, and then contribute in ways that would get them results and transformation in a specific area of their life.

But what specific community should you start or join? Bianchini has a plan to help you find out.

- (p.40) If you want anything to have a tangible, real impact in your life you need to make it a practice. Daily.

- (p.40) Purpose is a throughline in your life. … We call this your Current Story and there are five questions to structure it. 1) What stands out for you about your upbringing and background? 2) What have been the top three most pivotal experiences in your life? 3) What are your top three proudest achievements? 4) What are three times you’ve taken a stand? 5) When you think of the people you’ve been drawn to help, who are they?

- (p.41) To most effectively crystalize your purpose, the most potent and powerful place to find a clear intention for your time, talents, energy, and focus is in the future.

- (p.43) Create a ritual around [spending] thirty minutes. … Spend them imagining the future and asking yourself the same six questions every day. The ritual and repetition are key to unlocking something new and forcing yourself into a different headspace.

- (pp.43-47) These seven steps make up your Purpose 30. … Step 1: Take your phone, computer, iPad, and TV. Turn them off and slowly walk away. … Step 2: Make your favorite beverage. … Step 3: Have blank paper and a pen ready. … Step 4: Start by clearing out everything that’s on your mind. … Just write down everything you woke up thinking about. Drop all of it on its own blank piece of paper. … Step 5: Set the clearinghouse aside and establish context for your Purpose 30. … Start in the future and picture yourself looking backward. … It’s ten years from now, and you’ve uncovered a secret formula that lets you create the future you want. Your future state is positive, exciting, and unexpected. More than helping you alone, it’s a future where your impact is felt by others. You have a community, are surrounded by exciting challenges and unexpected opportunities, and you have the confidence to put your talents, time, energy, and focus towards anything you want to accomplish. … Step 6: Reflect on your Purpose 30 questions. … Now tackle these questions: 1) What are three things you’re able to do in the future that you’re not able to do today? 2) What are three things you’ve accomplished? 3) What are three things you have taken a stand for? 4) What has changed in your world for the better in the most unexpected and surprising way? 5) Who are the people you have brought together? 6) What are three things they are able to do in the future that they aren’t able to do today? … Step 7: Celebrate when your Purpose 30 is up. … After thirty days you willhave cultivated a picture that allows you—no one else—to define a positive intention and direction for your time, talents, energy, and focus. And you’ll have the blueprint for your next step. Your future story.

Great! But why are we building a community exactly?

- (p.69) If you take one concept away from this book, let it be this: The quickest and simplest way to translate your purpose into action is through community. Community not in the faux sense of an audience or fans who may talk to you but aren’t talking to each other. A true community is where connections are made, relationships are built, quests are undertaken, challenges are overcome, opportunities are seized, and people are transformed.

Okay. But “leading a community” sounds scary. Can I really do that?

- (p.72) A host is the most powerful role any of us can take on as we turn our purpose into action. A host can take many forms—gatherer, facilitator, guide, teacher, coach, mentor, or a warm, welcoming friend—but a host does something the rest of us increasingly don’t. They bring people together with intention. The intention to discover, explore, comfort, belong, teach, learn, solve problems, take on challenges, collaborate, celebrate, grieve, and so much more.

- (p.90) The single greatest way to start attracting people to your purpose isn’t to make a video espousing your views or expect someone to do exactly what you say to do. … It is easier and more effective to learn the art and science of asking great questions. They are going to do more to share your purpose with people than anything you can read, consume, or produce yourself.

- (p.90) I’m talking about questions that evoke meaningful responses and spark a connection between people. I call them community questions, and once you get the hang of them, they make nearly every interaction you have twice as much fun.

- (p.92) What makes a great question? Chances are it contains one or more of these four ingredients. 1) It taps into universal, human phenomena and common experiences a majority of people can relate to. 2) It is structured in such a way that it’s almost impossible to give a boring answer. 3) It ignites a domino effect of entertaining answers. Answers spur more answers. 4) It gives people an opportunity to share a part of themselves that they want to be seen.

- (p.93) Now that you have the ingredients, you need the recipe. … I finally landed on the idea of a question generator with two distinct elements—an unlocking phrase and a topic. An unlocking phrase is what your question starts with—it’s the frame and helps you focus in on one aspect of a broad topic. There are thousands of options, but here are my Top 10.

- What is your favorite…

- If you could…

- What do you value most in a…

- Name one thing…

- How do you know when…

- When was the last time…

- Where would you…

- What’s an unusual…

- As a child…

- What’s the first…

- (p.93) Then you combine your topic—your purpose—with the unlocking phrase. One unlocking phrase could generate endless amounts of questions, based on different topics and variations.

Being a “host” and asking questions doesn’t sound so bad. But who do I ask?

- (p.109) People who are new to hosting carefully plan their new community guided by perfection. In contrast, those who are ultimately successful accept the beauty of communities as decidedly imperfect and ultimately forgiving. They quickly get to the core questions they need to answer to start inviting folks in. Who is going to want or need my community the most right now? What results or experiences do they want to get? What kinds of activities will they do together? What new things will my members get or be able to do as part of my community? How am I going to make it exciting and awesome? The folks who thrive in this phase are those who realize quickly, “This is so much easier than people think.”

- (p.114) Your ideal member is the person who needs your community right now. They are the people who you want to attract first to help you bring your Future Story to Life.

- (p.115) The number one mistake I see with communities is not getting clear or specific enough at this stage with their Ideal Member. … Your Ideal Member, instead, needs to be brought to life with a story.

- (p.119) Write your Ideal Member’s story. First, start with the questions below… What transition is your Ideal Member navigating right now? Are they experiencing a loss or figuring out how to add something new to their lives? Are they starting something or ending something? What’s on their vision board for the life they’re living five years from now? What’s holding them back? Is it practical? Is it mental? A bit of both? What are they Googling late at night? What’s the biggest question they have right now? What are they losing sleep over? What does a typical day in their life look like? What emotions do they cycle though each day? Where have they looked for support already? Their spouse? Books? A therapist? A coach? Social media? A spiritual advisor?

Got it. But what are we going to talk about exactly?

- (p.126) Your Big Purpose is the motivation for your community—not just yours, but your members’ motivation. Why they’ll join, why they’ll contribute, and why they’ll walk arm in arm with you toward your Future Story.

- (p.127) Community builders tend to fall into two camps: 1) They try to create an elegant, almost “tag-line” like Big Purpose…something they can fit on a bumper sticker. Or 2) They write an essay combining their Future Story, their Ideal Member Story, and even their diary entries into a novel-like experience. Like most things, there is a middle path. It’s where the most successful Big Purposes end up.

- (pp.127-9) I’ve developed a simple, three-part formula that gives you enough room to be expansive and add the details. … Step 1: Identify the Transition. … The transitions in our lives are when we need community the most. It’s when we may find ourselves more isolated, because the people we need to go to are a part of our old life, and we don’t yet have any connections in our new life. … Step 2: Define the Results. … Be specific. … Be ambitious. … Step 3: Build a Bridge. … Describe how your Ideal Member will move from A to B, from their moment of transition to the results and transformation.

- (pp.129-130) Put it all together. “I / We bring together ____(your Ideal Members with a transition)____ to ____(the bridge, or the activities your members will do together)____, so that we can ____{achieve the results we want)____.

That’s a very clear and inspiring start. Then what?

- (pp.140-1) Your Community Design PlanTM is…a structure that guides your Ideal Members to your community—that gets them to answer the call—and takes them to a new future, a year from now, where they’ve achieved results and transformation they couldn’t imagine today. It has five elements. … 1) Your Big Purpose. 2) A Year in the Life. 3) Monthly Themes. 4) A Weekly Calendar. 5) Daily Polls and Questions. They start wider, with the overall motivation for your community, and then break it down by time period.

- (p.149) Your first digital members come from your core community.

- (p.152) Your superpower right now is that you know these people.

- (pp.158-60) Create a magical first experience. … The Enemy of Magic is the Expected. … Purpose + Connection + Surprise = Magic.

- (p.161) Instead of focusing on the mechanics and what not to do, focus on how someone can contribute, what they’re going to get out of it, and who’s there in it with them. It’s focused on joy and assumes the best of everyone who’s walking through the door. A community built on that foundation is going to be more focused and powerful than anything you’ve encountered before.

- (p.164) Your people and your people’s people are gathering around your Big Purpose. Energy is building. Ideal Members are joining, and you’re delighting them with a magical first experience. … How do you take all this emerging promise and potential and turn it into deeper impact, results, and transformations? … Quests!

- (p.164) Quests are the activities in your community designed to connect your members to each other and the results they want to achieve. Human beings are built for Quests, which help us belong to something bigger than ourselves, make connections to people on our same path, and master something interesting or important together.

- (pp.165) Quests can loosely be categorized into four types: courses, challenges, experiences, and collabs.

How fun. But not everything is done in a community. And not all of us can host a community, right?

- (p.172) If I haven’t made you a true community believer yet, that’s all right. You still have the potential to turn your purpose into a practice and develop more energy and resilience with any action you choose to take with just the Purpose 30 and your Future Story.

Amazing. This book really landed with me at a time I needed it most. I’ll write more on my own purpose and future story soon, but I wanted to share this first as a gift to all the ProSocial communities I’ve been involved with over the last 2+ years and to anyone else who’s still looking for more communities to join. Please get Bianchini’s book for more!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed