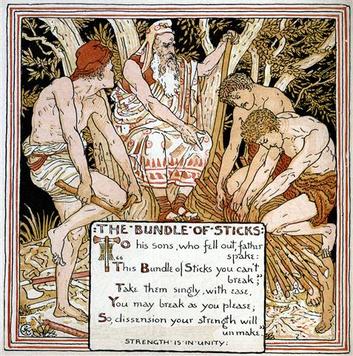

Aesop's Fable

The Father, His Sons, and the Bundle of Sticks

To his sons, who fell out, father spake:

“This Bundle of Sticks you can’t break;

Take them singly, with ease.

You may break as you please;

So, dissension your strength will unmake.”

Strength is in unity.

---------------------------------------------------

Here's something you can try at home. Or on the bus, for that matter. You can do it with your eyes closed or open, in a quiet room, or a noisy street. All you have to do is this: identify yourself.

I don't mean stand up and say your name. I mean catch hold of that which is you, rather than just the things that you do or experience. To do this, focus your attention on yourself. Try to locate in your own consciousness the "I" that is you, the person who is feeling hot or cold, thinking your thoughts, hearing the sounds around you and so on. I'm not asking you to locate your feelings, sensations, and thoughts, but the person, the self, who is having them.

It should be easy. After all, what is more certain in this world than that you exist? Even if everything around you is a dream or an illusion, you must exist to have the dream, to do the hallucinating. So if you turn your mind inwards and try to become aware only of yourself, it should not take long to find it. Go on. Have a go.

Any luck?

Source: Book I of A Treatise on Human Nature by David Hume, 1739-40.

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 160.

---------------------------------------------------

I was quite excited when I first saw that this experiment was taken from David Hume. He's the Scottish philosopher who finished second in my Survival Rankings of the 60 Fittest Philosophers, and whose property I once visited in order to walk in his footsteps right around the time I was publishing a paper that proposed a metaphorical bridge across his famous is-ought divide — moral philosophy's greatest conundrum. Hume's writings have sparked many a deep reflection for me, but unfortunately (for this post anyway), I've already blogged extensively about his writings on the topic of personal identity. Oh well, it shouldn't hurt to recap and extend a bit.

By my count, this continually questioned topic of personal identity has cropped up in 11 of the 54 thought experiments I've covered so far. In the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Personal Identity, we can see a little bit of why this is the case. According to that essay: "There is no single problem of personal identity, but rather a wide range of questions that are at best loosely connected. There is no consensus or even a dominant view on this question [but] here are some of the main proposed answers (Olson 2007):

- We are biological organisms (“animalism”: Snowdon 1990, 2014, van Inwagen 1990, Olson 1997, 2003).

- We are material things “constituted by” organisms: a person made of the same matter as a certain animal, but they are different things because what it takes for them to persist is different (Baker 2000, Johnston 2007, Shoemaker 2011).

- We are temporal parts of animals: each of us stands to an organism as the first set stands to a tennis match (Lewis 1976).

- We are spatial parts of animals: brains, perhaps, or parts of brains (Campbell and McMahan 2010, Parfit 2012; Hudson 2001 argues that we are temporal parts of brains).

- We are partless immaterial substances—souls—or compound things made up of an immaterial soul and a material body (Swinburne 1984).

- We are collections of mental states or events: “bundles of perceptions”, as Hume said (see also Quinton 1962 and Campbell 2006).

- There is nothing that we are: we don't really exist at all (Russell 1985, Wittgenstein 1922, Unger 1979).

I need to read more about these recent "animalism" proposals—they sound like they are related to my evolutionary worldview—but I also think Hume's "bundle theory" got a lot right when he used it to oppose Aristotle's, Descartes', and many other's concept of a single, immutable, immaterial soul as the eternal seat of our personal identity. As I wrote in my Response to Thought Experiment 38: I Am a Brain:

According to bundle theory, "an object consists of its properties and nothing more: thus neither can there be an object without properties nor can one even conceive of such an object; for example, bundle theory claims that thinking of an apple compels one also to think of its color, its shape, the fact that it is a kind of fruit, its cells, its taste, or at least one other of its properties. Thus, the theory asserts that the apple is no more than the collection of its properties." The clarity that bundle theory brings ... comes when you imagine taking away all the properties of an object one by one until all of them are gone. Once that is done, according to Hume, nothing of the object is left.

To make that even more relevant to this week's thought experiment, here are Hume's own words from A Treatise on Human Nature, where he applied his bundle theory to personal identity:

For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception. When my perceptions are removed for any time, as by sound sleep, so long am I insensible of myself, and may truly be said not to exist. And were all my perceptions removed by death, and could I neither think, nor feel, nor see, nor love, nor hate, after the dissolution of my body, I should be entirely annihilated, nor do I conceive what is further requisite to make me a perfect nonentity. ... Suppose the mind to be reduc'd even below the life of an oyster. Suppose it to have only one perception, as of thirst or hunger. Consider it in that situation. Do you conceive any thing but merely that perception? Have you any notion of self or substance? If not, the addition of other perceptions can never give you that notion.

I really appreciate this paring back of personal identity to that of the simplest organisms. It's all the more remarkable coming from Hume since he did this more than 100 years before Darwin's theory of natural selection explained evolution. As we now know for certain, we have evolved from these simple organisms with singular perceptions though, so whatever notions we have about our own identity must be tied to theirs as well. For me, I'm persuaded that all of our identities and consciousnesses are mere accretions of perceptions, one stick at a time, until the united bundle of them gives a strong, almost unbreakable, illusion of an underlying unity. Watch any individual slowly lose their perceptual abilities one-by-one as they age toward the grave, however, and you see their personal identity snap away one twig at a time. Likewise, looking at the personal identity of non-human animals, if you take away just a few of the higher-order brain functions that we homo sapiens have evolved of late, then you aren't left with a soulless zombie, you just get another animal with a slightly smaller bundle of abilities, thoughts, and emotions. So, this bundle theory view of the self may take away some personal, religious notion of a lonely, individual, immortal "I", but in return it binds us together with all of the rest of life who are in the same boat as "we" are. Isn't that a much stronger concept to adhere to?