--------

DSW: If we want to eliminate suffering from the whole word, we need to turn the whole world into a single organism. So that is something which is entirely within the bounds of hard science, methodological naturalism, no mythic, no nothing. There is actually an agenda which we can pursue. I think that’s a pretty big deal. Not just in the novel, but in the real world. This motivates a whole earth ethic and a path for expanding what we mean by organism to larger and larger scales.

MS: Just to put a pin on that, you are doing what I have been trying to do, and Sam Harris, and to a slightly lesser degree Steven Pinker, and that is bridging the is-ought barrier. As you know, Hume famously said you can’t go from an is to an ought. But in a way, that sounds exactly like what you are doing. Like, “We ought to structure society based on some way nature is (in this case, human nature).” And you’re comfortable doing that?

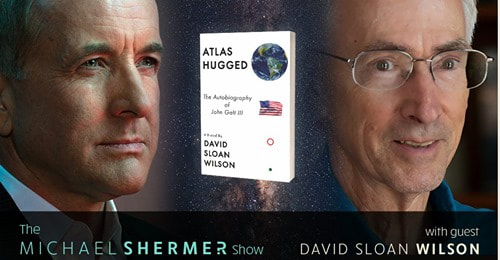

DSW: Yeah, I am. I’ve been having a wonderful conversation with an evolutionary philosopher named Ed Gibney. It’s actually on Letter Wiki. If your audience doesn’t know about Letter.Wiki, it’s a wonderful forum for respectful conversations where two people get together and they write letters to each other which are available to the public, but it has the respectful quality of two friends communicating with each other in a respectful fashion as they would if they were writing letters to each other. And Ed I think did something brilliant. I don’t think it was necessarily something original, and he wouldn’t say that it was, but he says let’s add a third word to is and ought. That third word is want. And so although ought cannot be derived from is, it can be derived from is plus want. So if I want a glass of water and the only water is available in a spring a mile up the road, I ought to go to that spring to satisfy my want. This is what Hume meant perhaps when he said reason is the slave of the passions. We can’t really employ reason unless we want something. And so I think that that really is brilliant given all of the press that’s given to the so-called naturalistic fallacy. To think that all we need to do is to add a third component, the desire component, and it’s at that point, if we want to do something, we need to consult the world as it is in order to achieve that want. Have you encountered that? Don’t you think that’s kinda good?

MS: Yeah, I like that. I like that a lot. But I don’t have any trouble going from is to ought because if you study human nature and social science it seems like it’s pretty clear, at least in the general form of things, it’s better to be free than enslaved, it’s better to be satiated than hungry, it’s better not to be tortured, it’s better to be healthy rather than diseased and so on. And once you recognize that that’s human nature, that’s a universal, then we ought to strive for that. I think that’s what the liberal tradition ever since the Enlightenment has been moving toward: this kind of more universal ethic that borders more on utilitarianism and consequentialism than say a Kantian rule-based deontology.

--------

How cool is that! It's great to see philosophy make it into real world discussions. (Particularly for me, my own little independent philosophy!) To follow up on this, I told Michael and David on Twitter that using any old wants to get from any old is to some specific oughts is not my invention, but trying to find the right wants that give us moral oughts does seem to be my unique contribution (as far as I know). To illustrate this using David's example, if you want a glass of water, and the only water is in a spring up the road, then yes, you ought to go to the spring. This is just a simple logical argument using a conditional premise (i.e. if x, then y). But the real question is how do you justify that first premise? In this case, how do you know it's okay for you to want water? We surely don't think all of our wants justify oughts as good ones to fulfill.

Readers of my original paper on this will know that I trace it all back to the survival of life. That's the most fundamental want that exists, which turns it into a need. Without life, there are no oughts at all. And so just as Darwin flipped the design of life on its head in a strange inversion, which replaced a designer from on high with a relentless bottom-up blind process, I believe morality should be looked at the same way. Moral oughts grow more and more complex for life as more and more knowledge and choices become available and more and more robustness becomes possible. As I told Michael and David on Twitter, I believe the next trick is to recognize that these wants and needs are being selected for and have grown over time. I believe they have grown into something like my evolutionary hierarchy of needs, which replaces Maslow's needs that were narrowly focused on human individuals alone.

All of this is stands on much firmer ground than Michael Shermer's proposed guidance that "It's better to be free than enslaved, it's better to be satiated than hungry...and so on." First of all, it's not always better to be satiated than hungry. If that rule were always followed, obesity would follow soon thereafter. Secondly, the "and so on" is where the rub lies. Morality is not about the easy choices; it's about the hard ones. And Shermer offers no guiding principles for that here. (Maybe he does elsewhere?) In fact, he sorta makes a bad blunder by saying "that's human nature, that's a universal...we ought to strive for that." Almost by definition, there's not that much of significance that is universal in human nature. If anything is truly universal, then there is no choice about it. But there are plenty of possible things in all of our natures, and some of those are grand some of the time, and some of those are abhorrent some of the time. We need a guiding principle to know which ones are which and why.

I go into this in some more detail in my 9th letter to David in our Wiki conversation, where I describe how to reconcile the three main traditions of moral philosophy—consequentialism, virtue ethics, and deontology—but I'll leave that discussion for another time as I'm working on turning that into a published paper later this year. For now, I just wanted to draw some attention to this discussion.

What do you think? Is David right that my is-want-ought formula is something "brilliant" in the struggle to decide what we ought to do? Let me know in the comments below.