Before this week's thought experiment send us off to explore this enormous question, I thought it might be helpful to read a few basic definitions. Querying Google today gave me:

Art - (noun) the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.

Over on the wikipedia entry for art, we see:

Art is a diverse range of human activities and the products of those activities, usually involving imaginative or technical skill.

These broad generalizations sound simple enough, but among philosophers, artists, and critics throughout history, there have been many details to quibble over concerning this subject. After a day spent reading widely-varying thoughts on the definition of art, perhaps the one that makes the most sense came from Theodor Adorno who claimed in 1969:

It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident.

Let's take a look at the thought experiment now though, and then try to decide what might be evident to an evolutionary philosopher.

---------------------------------------------------

Daphne Stone could not decide what to do with her favorite exhibit. As curator of the art gallery, she had always adored an untitled piece by Henry Moore, only posthumously discovered. She admired the combination of its sensuous contours and geometric balance, which together captured the mathematical and spiritual aspects of nature.

At least, that's what she thought up until last week, when it was revealed that it wasn't a Moore at all. Worse, it wasn't shaped by human hand but by wind and rain. Moore had bought the stone to work on, only to conclude that he couldn't improve on nature. But when it was found, everyone assumed that Moore must have carved it.

Stone was stunned by the discovery and her immediate reaction was to remove the 'work' from display. But then she realized that this revelation had not changed the stone itself, which still had the qualities she had admired. Why should her new knowledge of how the stone came to be change her opinion of what it is now, in itself?

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 109.

---------------------------------------------------

Seeing this, one would assume that philosophers must have something profound to say about this thought experiment, but they have actually had quite a thin and terrible track record. At least among the 60 major philosophers I profiled in my series on the Survival of the Fittest Philosophers. During all those posts, I found:

- Plato only listed a threefold division of philosophy: metaphysics, ethics, and physics.

- Muhammad decreed a prohibition against creating images of sentient living beings, which is particularly strictly observed with respect to God and the Prophet. Islamic religious art is focused only on words.

- Descartes doesn't mention aesthetics in his view of the nature of philosophy. He thought: Philosophy is like a tree, of which Metaphysics is the root, Physics the trunk, and all the other sciences the branches that grow out of this trunk. By the science of Morals, I understand the highest and most perfect, which, presupposing an entire knowledge of the other sciences, is the last degree of wisdom.

- Rousseau actively disparaged the field. He thought: The arts and sciences have not been beneficial to humankind, because they arose not from authentic human needs but rather as a result of pride and vanity. Moreover, the opportunities they create for idleness and luxury have contributed to the corruption of man.

- Kant marked a slight change in this with his Critique of Judgment, which investigated aesthetics and teleology, but his view was quite clinical. Kant divided the feeling of the sublime into two distinct modes - the mathematical sublime and the dynamical sublime. The mathematical sublime is situated in the failure of the imagination to comprehend natural objects that appear boundless and formless, or that appear absolutely great. This imaginative failure is then recuperated through the pleasure taken in reason's assertion of the concept of infinity. In the dynamical sublime, there is the sense of annihilation of the sensible self as the imagination tries to comprehend a vast might. This power of nature threatens us but through the resistance of reason to such sensible annihilation, the subject feels a pleasure and a sense of the human moral vocation. This appreciation of moral feeling through exposure to the sublime helps to develop moral character.

- With Schopenhauer, we got a very dour purpose for art. He thought: A temporary way to escape the pain of life is through aesthetic contemplation since art diverts the spectator's attention from the grave everyday world and lifts him or her into a world that consists of mere play of images. This is the next best way, short of not willing at all, which is the best way.

- Even Sartre, an extremely successful novelist and playwright, was not immune to dismissing art. Originally, Sartre believed that our ideas are the product of experiences of real-life situations, and novels and plays can well describe such fundamental experiences, having equal value to discursive essays for the elaboration of philosophical theories such as existentialism. Later, Sartre concluded that literature functioned ultimately as a bourgeois substitute for real commitment in the world, and thus turned down a Nobel Prize for literature.

- Many philosophers wrote works of art to illustrate their beliefs—Plato's Republic, Erasmus' In Praise of Folly, Bacon's New Atlantis, Voltaire's Candide, Rousseau's Emile, Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Sartre's No Exit and Nausea, Rand's The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, de Beauvoir's All Men Are Mortal. But only Ayn Rand seemed totally at ease with the role of art in her work (although her credibility as a philosopher is much less comfortably assured). Rand's aesthetics defined art as a "selective re-creation of reality according to an artist's metaphysical value-judgments.” According to Rand, art allows philosophical concepts to be presented in a concrete form that can be easily grasped, thereby fulfilling a need of human consciousness.

I suppose this is to be expected from a field that rewards logic above emotion and draws people to it whose personalities are dominated by reason. Aristotle, who was known as "The Philosopher" for almost 2000 years, thought that the universal elements of beauty were order, symmetry, and definiteness. Logical, logical, and logical.

From the late 17th to the early 20th century, Western aesthetics continued on this rational path as it "underwent a slow revolution into what is often called modernism." Artists began to emphasize beauty as the key component of art and the more analytic theorists among them tried to reduce beauty to some list of attributes. Famed painter and social critic William Hogarth, for example, thought that beauty consisted of:

- fitness of the parts to some design;

- variety in as many ways as possible;

- uniformity, regularity or symmetry, which is only beautiful when it helps to preserve the character of fitness;

- simplicity or distinctness, which gives pleasure not in itself, but through its enabling the eye to enjoy variety with ease;

- intricacy, which provides employment for our active energies, leading the eye on "a wanton kind of chase"; and

- quantity or magnitude, which draws our attention and produces admiration and awe.

None of these logical or objective definitions of art and beauty so far would have considered the stone in this week's thought experiment to properly be art. It was only during the first half of the twentieth century that a significant shift to a more relaxed aesthetic theory would have allowed that. At the end of the First World War, Dadaists came on the scene who "believed that the 'reason' and 'logic' of bourgeois capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expressions that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality." Found object art is perfectly illustrative of this belief, and Marcel Duchamp is thought "to have perfected the concept when he made a series of ready-mades, consisting of completely unaltered everyday objects selected by Duchamp and designated as art. The most famous example is Fountain (1917), a standard urinal purchased from a hardware store and displayed on a pedestal, resting on its side."

Duchamp once proposed that art is any activity of any kind—it is everything. So for him, there would be no question of whether the stone in this thought experiment would be art. I tend to agree with a contemporary critic though who stated that "Dada philosophy is the sickest, most paralyzing, and most destructive thing that has ever originated from the brain of man." Duchamp's stance reminds me of the old adage, if you don't stand for something, you'll fall for anything. And so it is only the people with no definition for art who fall for Duchamp.

But perhaps no definition for art is possible. Another approach "is to say that art is basically a sociological category, that whatever art schools and museums and artists define as art is considered art regardless of formal definitions." This is known as the "institutional definition of art." But can we really listen to art authorities? Who gets to choose who gets to decide?

As influential critics Wimsatt and Beardsley wrote in their highly influential 1954 essay The Intentional Fallacy: "the design or intention of the artist is neither available nor desirable as a standard for judging the success of a work of art." This basis for postmodern frameworks places the reader's interpretation ahead of any authorial intent. It makes the reader or consumer of the art the only authority on its meaning. Of course, to finish off the confusion, Wimsatt and Beardsley wrote another essay called The Affective Fallacy, which discounted the viewer's personal/emotional reaction as a valid means of analysing art too.

So what are we left with? Definitions for art and aesthetics have swung wildly from rigid, numbered rules, to absolutely no rules at all. Postmoderns don't listen to artists or their audience for any judgements. In my post What is Beautiful is What is Good, I described this confusing state of affairs thusly:

The longstanding and pervasive view that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder" seems to suggest that aesthetics isn't objective, that aesthetics is a subjective field filled with personal judgments from sensitive souls inside a landscape of cultural relativism. When you travel around the world or look at the development of art through history, you see very different representations of beauty: Vogue's rail thin models, Gauguin's plump Polynesians, Japanese Zen gardens, Jackson Pollock's paint drippings, a delicate rose, a powerful stallion, a touching novel, an elegant spreadsheet. (Or am I the only one who has ever exclaimed, "That's beautiful!" during an annual budget meeting?) The obvious question arises - how can these beautiful things have anything in common?

In my own philosophical writings on aesthetics, however, I offered the following answer (starting from my definition of good that arises from nature):

What promotes the long-term survival of life? Knowledge. Health. Progress. Stability. Exploration. Efficiency. Brightness. Abundance. Comfort. Security. Fecundity. Clarity. These are beautiful and good. What threatens the long-term survival of life? Ignorance. Disease. Stagnation. Conflict. Chaos. Isolation. Waste. Darkness. Scarcity. Discomfort. Vulnerability. Barrenness. Obscurity. These are ugly and bad. Objects have many qualities. Depending on the context, focus, and cognitive appraisal of the observer, objects can be either beautiful or ugly. This is why the idea of beauty is objective to general reality, but the beauty of an object is subjective to the specific observer.

Science is the root method of gathering knowledge. Engineering is knowledge applied to the physical world. Business is knowledge applied to the economic world. Politics is knowledge applied to the realm of government. Medicine is knowledge applied to the body. Art is knowledge applied to the emotions. Science finds knowledge. Art uses knowledge to inspire. (It can also inspire scientists.) Art causes emotional responses so it often draws emotional people to it, but great art is created by rational processes, filled with knowledge, fueled by emotion, and executed with skill. Bad art is blind emotion that purports falsehoods for truth.

After doing my research for this post, I would add the following addenda to these thoughts now. I agree with those who believe that "if the skill of a creator is used for a functional object, that is considered a craft rather than art" (though this is disputed by many Contemporary Craft thinkers). Likewise, "if the skill is being used in a commercial or industrial way it may be considered design instead of art" (although these may be defended as art forms or called applied art). I find these to be useful distinctions, though I'm sure they are not always easy to apply.

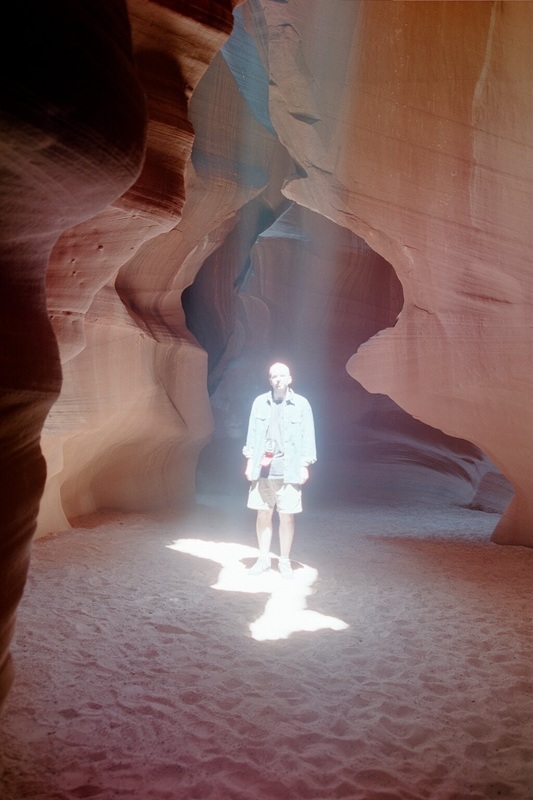

As far as applying all of this to the thought experiment at hand, I would judge the untouched stone as art, but only a very weak piece of art. It's not a functional object useful for another purpose. It was a found object, selected by two humans (the sculptor and the curator) whose eye for beauty is well trained, but their full creative skills have not been put to much use. I imagine the smooth patterns of erosion hewn from such a solid piece of material would put me in touch with Kant's definition of the sublime, and inspire me to think a little more about the long-term impact I have on this world, but probably less so than any observant walk in nature would do for me.

What do you think? You probably wish you'd gone on that inspiring walk rather than read through such nitpicking. I feel like such a boring philosopher.