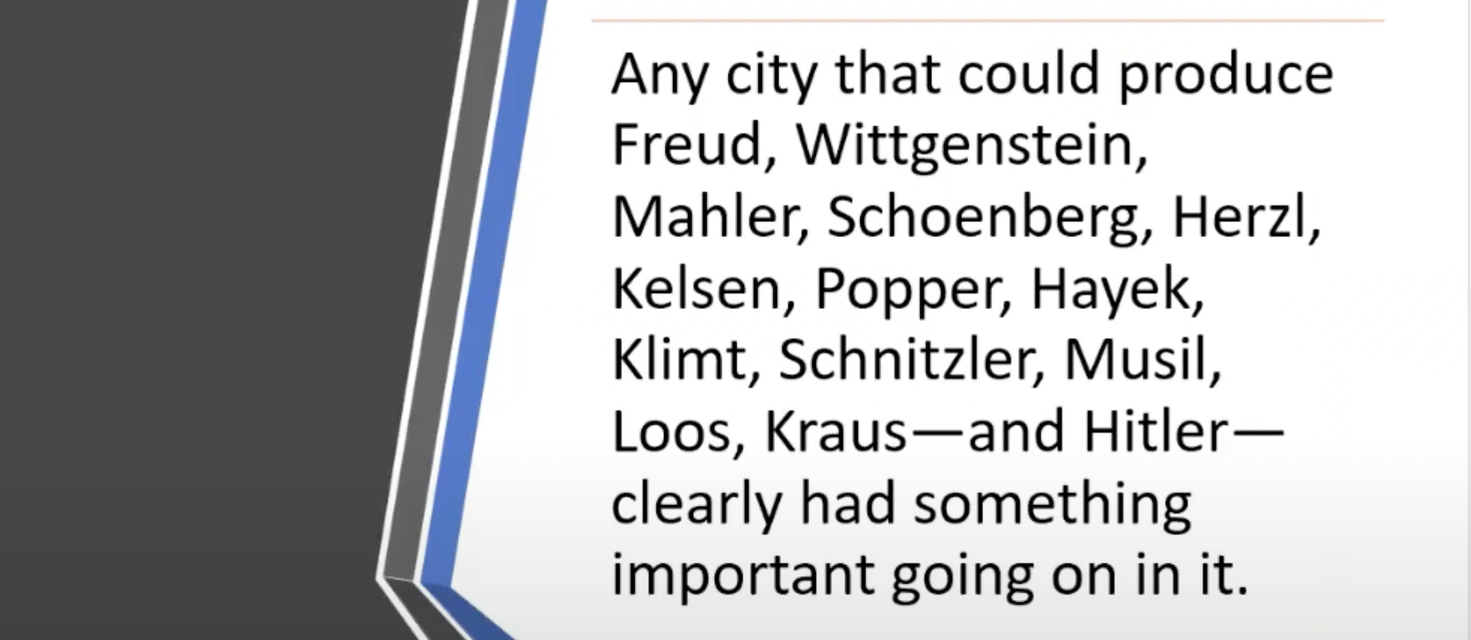

Since the Vienna Circle made for such an inspiring example of what a philosophy group could do, I thought I'd invite David Edmonds to speak to our new group about them. Not only did he accept, but he also ditched the usual talk that he gives about philosophy for this book, and instead, he shared with us a new theory he had for why Vienna was so unusually successful. The Vienna Circle may be rather famous among philosophers, but it was actually just one element of an extraordinary profusion of cultural and intellectual projects that occurred in Vienna during the first few decades of the 20th Century. Edmonds likened this to Edinburgh in the 18th century, Florence in the 14th & 15th centuries, and Athens in 400 BC.

- Money — Perhaps the most prominent member of the Vienna Circle was Ludwig Wittgenstein, who happened to also be one of the richest men in Austria. He didn't exactly fund the Vienna Circle, but he and his family were emblematic of the kind of wealth that had circulated around Vienna for centuries, giving patronage to so many cultural and intellectual pursuits. This long history of empire gave Vienna a lot of assets to work with.

- Politics — The Vienna Circle met regularly between 1924 and 1936 and it's no accident that this was during the interwar years between the fall of the Hapsburg Empire and the rise of National Socialism. Massive inflation wiped out much of Austria's wealth. The loss of the Great War had been a great humiliation. And these are the kinds of circumstances that bring out extremes. Nobody could be politically apathetic at a time like this.

- Ethnicities — Over half of the Vienna Circle were Jews who, as a people, were only a few generations removed from ghettos. This had unleashed a tidal wave of energy and enthusiasm in people who were desperate to assimilate into a vibrant society. But it wasn't only Jews. As the center of a centuries-old empire, Vienna was a true melting pot filled with Hungarians, Czechs, Poles, Slovenes, Serbs, and native Austrians, all of whom brought a wide variety of ideas together.

- Circles — None of these assets, fervor, or diversity would create something new, however, if there wasn't an intermingling of communities. Ideas remain stuck in place if they only persist in monocultural ghettos (along any variable of culture you can imagine). So, where did this intermingling occur in Vienna? This is worth an extended quotation from David Edmonds' lecture:

"You might expect that a key institution in the spread of ideas in Vienna would be the University of Vienna — the pre-eminent university in Austria, and before that, the pre-eminent university in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But in fact, the University of Vienna was a bastion of conservativism and operated using rigid racial quotas. Professors were unapproachable and did not encourage interaction with students. So, no, the transmissibility of ideas took place elsewhere and there were two main routes. The first one is illustrated [in the picture at the top of this post]: circles! The Vienna Circle actually met around a long table; it really should have been called the Vienna rectangle. But a “circle” was a more or less formal group of people who met to discuss a particular topic. The Vienna Circle was only one of many such circles. And these circles flourished in Vienna precisely because the official lectures in the university did not lend themselves to free discussion. So, crucially, many people were members of more than one circle. Carnap, for example, went to a circle run by the philosopher Gomperz, which covered economics, politics, and psychoanalysis, as well as philosophy. That was held on a Saturday. He went to another one on a Wednesday night, a circle that was run by the psychologists Karl and Charlotte Bühler. And many members of the Vienna Circle also went to Karl Menges mathematical circle. Circles had very different ways of operating. Some were more formal than others. Some were right-wing, others were left-wing. Some were more welcoming than others. Some did not include women. As for the Vienna Circle, this was effectively run by the German-born Moritz Schlick and Schlick chose whom to invite. And if he took a dislike to you, you would be excluded, as Karl Popper was to find out to his cost." - Coffee — In addition to the formal and informal circles, the second mode of transmission for ideas was via the famous coffee houses of Vienna. Here you could play chess, read newspapers, eat pastries and strudel, or drink a cup of coffee all day long. The coffee houses acted as a sort of democratic club with an extremely cheap price of admittance. And there were heaps of them! There were possibly more than 1,000 in Vienna during the 1920’s and 30’s. This is not a sprawling city, either, so people were continually bumping into others they knew as they floated from cafe to cafe where different groups usually met. Many coffee houses even had the practice of reserving a “stammtisch” or "regular's table" for these welcoming discussions. And unlike in a university or other formal setting, the coffee shops offered a more relaxed environment where tentative views could be floated and wild theories could be exchanged.

These elements make a lot of sense to me. They remind me of the stories I often read about San Francisco and the unique success of Silicon Valley when I lived there in the 1990s. Could this theory be tested, however, as the Vienna Circle might insist? Well, David Edmonds cited the work of scholars from a variety of disciplines who have been studying the success of cities, and they have broadly reached the same conclusion: what is required for ideas and economies to flourish is interaction, interactivity. That’s clearly something that Vienna had in abundance, and something others would do well to copy.

For those of us that want to bring about a more Prosocial World, the question then becomes whether we can recreate this online. With an ability to draw people from all over the world, we can clearly meet the first three criteria in David Edmonds' hypothesis. There are a wealth of ideas out there from a diverse group of people who are all highly motivated to change the failing politics we see everywhere. The difficulty, then, is getting a profusion of circles going where people can intermingle in a relaxed and productive manner. How do you best encourage that?

I've mentioned before that the philosophy circle I'm leading is just one of many such groups establishing themselves on the Prosocial Commons. We've all just taken a slight break at the end of our first 12-week generation of activity (kind of like a semester break in between courses at a university), and a few of us have joined a "steering committee" to review what we have learned and help take the next steps ahead. David Edmonds' presentation — which you can watch in full below — will surely give us something to think about.

This is an enormously exciting opportunity to me, and one that's about to be informed by much more in-depth research on Vienna. I mentioned at the top of this post that I would say why I had been reading David Edmonds' book in the first place, and that is because my wife and I were considering a move to Vienna. Well, I'm very happy to report now that my wife was recently offered a job there with the United Nations, which she has accepted. So, we'll be heading to Vienna in early November. If any of you want to come for a visit, I'll do my best to get a stammtisch set up where we can have a great long chat about all of this. Prost!