I've been talking for a few posts now about wrapping up my essays on philosophy and using this space to share fiction that discusses and displays the ideas I care about. Well, here goes. Way back in June 2016, the American Philosophical Association posted an advertisement for a short story competition. Entries were due February 2017, and winners were announced at the end of April. I did not win, but the first place and second place entries were published in June on the Sci Phi Journal's website. The people running the contest initially said they were going to put together an edited volume of selected stories from a few of the 704 entries they received, but since I haven't heard anything about that yet, I'm going to assume it's safe to finally share my entry here. As noted in the competition rules, entries had to be "at least 1,000 words and no longer than 7,500 words. The submission should also be accompanied by a brief "Food for Thought" section (maximum word count: 500, not part of the overall word count), where the author explains the philosophical ideas behind the piece." So, without further ado, here is my entry (2538 words) and its accompanying food for thought (another 479 words). Your reactions and critiques will be most welcome!

Subject two; experiment one. Programmed minimum temperature is 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Actual room temperature will be maintained at 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Hello, Sergei. Are you there? Can you hear me?”

There was a slight pause, but then the words began to scroll across the monitor. “Yes. I am here. Everything is as you said it would be.”

“Very good. Can I confirm your thoughts? I believe you said, ‘Yes. I am here. Everything is as you said it would be.’ Is that correct?”

“Yes, doctor. That is correct.”

“Excellent. Do you know where you are?”

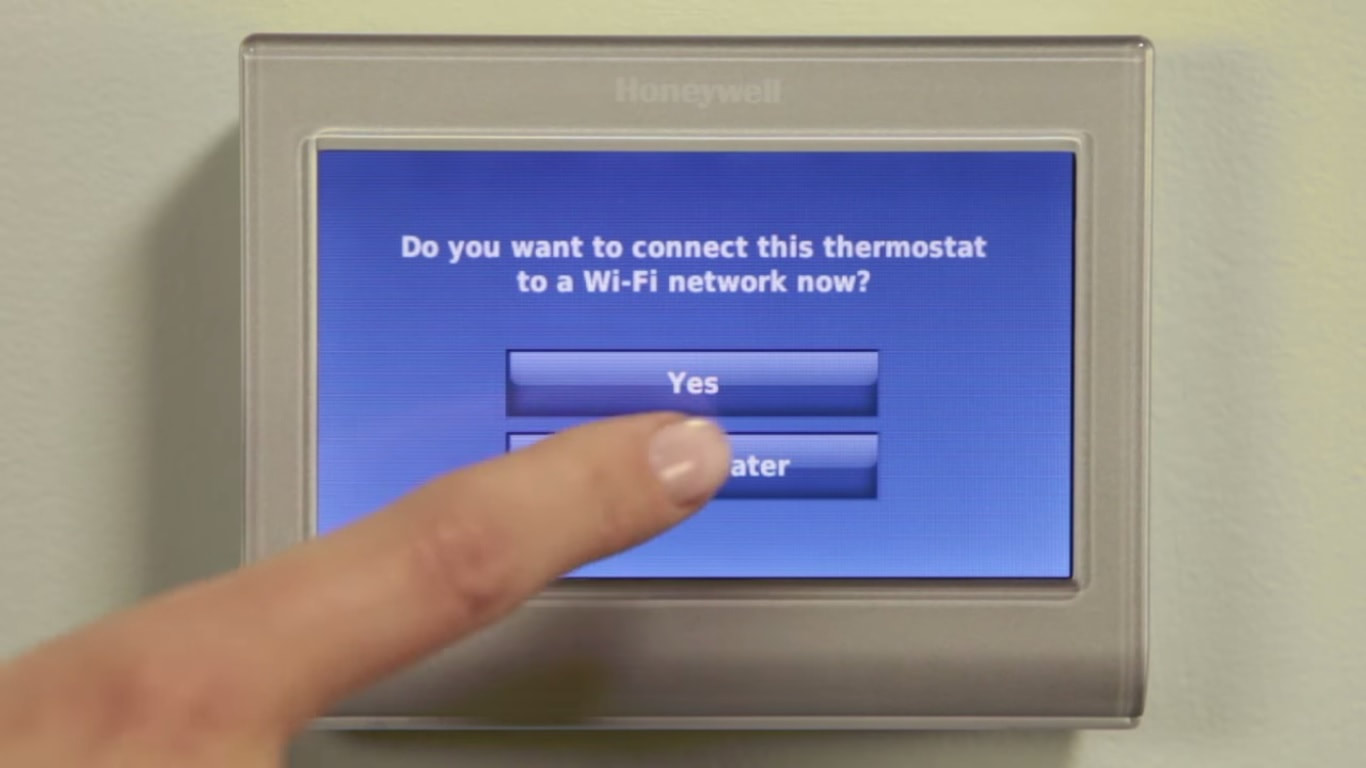

There was another slight pause, shorter this time, but then this: “Yes. I know I am in a thermostat, but it feels like I am sitting in the room with you.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, that’s not exactly right. I have no physical sensation of sitting. But I can hear you clearly and I have some idea that the room is comfortable. It’s like I am floating in here with you. And there’s no pain anymore. It’s great!”

“Very good, Sergei. Do you remember why you are here?”

“Because I didn’t want to die! Heh. Wait. I am laughing. Can you tell that I am laughing?”

“We pick up the words you think Sergei, and the computer registers your questions and exclamations too. So yes, I can gather some of your emotions from that. I need to keep verifying that you have survived the upload, Sergei. Can you please tell me what else you remember about why you are here?”

“Ah, let’s see. I drank too much. I got cancer. I only had a few months to live. You offered me this chance to continue in a thermostat and I said sure, why not. It’s probably nicer than my apartment.”

“And is it, Sergei? Nicer?”

“So far, yes! It’s quiet here. Nice and calm. No smell either.”

“Very good, Sergei. Next, can you tell me if you are hungry or thirsty?”

There was a long pause. “No. There is nothing like that. I can remember food and water. And vodka. But I cannot taste them. There is no saliva in my mouth. There is no mouth. I cannot explain it exactly. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, I think so, Sergei. Does that bother you?”

Short pause. “No! It’s a lot like being very drunk. It’s pleasant, actually.”

The doctor laughed at this. “Excellent. Since you’re in such a good mood, let’s check on a few more things. I want to see what you remember about your past, Sergei.”

“Okay. Go ahead.”

“How old are you?”

“I am forty five.”

“Where did you live last week?”

“I was living in Chernaya Gryaz, a village outside of Moscow. I lived there for almost twenty years.”

“Good. And where did you live when you were five years old?”

“I was born and raised in Astrakhan. My father and grandfather were fishermen in the Caspian Sea. It was a great place for a child. Not so much for an adult.”

“Why is that? Why did you leave?”

“Well, when the caviar ran out, there was no work for someone like me.”

“Like you?”

“You know—without protection. Mafia controlled the sea, my parents died, and I moved to Moscow to drive trucks.”

“Do you have a family?”

Short pause. “No. I never met the right girl. I met plenty of wrong ones though if you know what I mean!”

“I understand. No brothers or sisters?”

“No, I was only child.”

“Excellent. It seems to me like you can remember your past quite well. Are you experiencing any difficulties recalling these details?”

“No. If anything, it’s easier.”

“Very good. I told you we had enough storage, and that as long as you had your memories you would still feel like yourself. So can you tell me, Sergei, do you still feel that you are you?”

“So far…I have to say yes, doctor.”

The doctor flicked off the switch to Sergei’s microphone, but made a statement aloud for the room’s monitors.

“Memory and personality seem intact. Despite the differences from biochemical functioning, the mimicry of the computer’s neural network seems to be accurate enough to convince the subject. First conditions may be considered successful. We may move to the second test as soon as the room is ready.”

The doctor turned Sergei’s microphone back on, but left the room to go out for a lunch break.

Subject two; experiment two. Programmed minimum temperature is 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Actual room temperature will fall slowly from 70 degrees to 67 degrees, before returning back to 70 degrees.

“Hello again, Sergei. I would like to check in on you if you don’t mind. How are you doing? What have you been thinking about?”

“Doctor, hello. It is good to hear your voice again. I am fine, but…”

“But what?”

“Nothing. I am not sure. It’s just that…I’m finding it hard to concentrate on anything. When you are talking to me, it is easy to focus on our conversation. But when no one is talking I am overwhelmed by the random noises of the room. Shuffling feet. Turning pages. A dropped pen. A cough. These all bring a flood of different thoughts to my surface and I cannot seem to tune them out.”

“Hmm. That’s disappointing to hear.”

“Wait. Why would you say that? I’m doing the best that I can. I’m sure it is just the new position that I am in. Don’t be disappointed. I will improve. Is there some kind of filter you can install? Please don’t turn me off like the first subject.”

“How do you know about that?”

“About what?”

“About the first subject.”

There was a pause on the readout before the next words came through. “Masha warned me about it right before the upload.”

The doctor was the one to pause this time, but then said sternly, “She should not have done that.”

“What do you mean? Why? It doesn’t matter to me. I already knew there was a big risk in this, but it was better than certain death. I mean, I had hopes this could last forever and that you could easily transfer me to a more interesting location once you knew I was safe, but... And I am safe. You can trust me. Aauugh! WHY IS IT SO COLD? IT’S SO COLD! SO COLD! Are you shutting me down? What is happening?”

“Everything is fine, Sergei. The temperature of the room has dropped slowly and your circuits are just telling the heater to come on. This will take a few minutes to have an effect.”

“How do I know this is true? I cannot see you! I know I’m not an important person! And I was about to die anyway! The Soviets sent dogs and chimps into space long before they knew it was safe! Cosmonauts too! Now you want to explore uploading consciousness in the same reckless fashion! I know it! I’m expendable! I just know it! Ah…wait a second. Something has changed.”

“What is it? What do you feel, Sergei?”

There was a long pause. Then Sergei responded. “I’m sorry but this is all new to me. Please forgive me. I felt what I would describe as a large outflow of energy—like I was exhausting myself rapidly. But now it is better. Only…”

“Yes? Go on.”

“Only now I suddenly notice a very small trickle of energy that seems to be leaving from the same location as the large outflow. I hadn’t noticed that before. It is a constant and unchanging feeling, but now I have something to compare it to. Where is that coming from? Am I only powered by batteries? Will they run out? What will happen when they do? I’m sorry for accusing you of mistreating me. Please forgive me. Please forget what I said. I’m still getting used to this.”

“Don’t worry about that, Sergei. Everything will be okay and you still have a very long time to live. I will turn your microphone off now to let you think in peace.”

“You can do that?”

“Yes of course. Let’s see if that helps you.”

Subject two; experiment three. Programmed minimum temperature is 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Actual room temperature has dropped suddenly to 65 degrees and will remain there for one hour.

“Okay, Sergei. I have turned your microphone back on. Can you hear me know? How was your time alone?”

“Come on! Come on! Come on! Come on!”

“Sergei. What is the matter? Is something wrong?”

“Why are you torturing me like this!”

“Torture? We are not torturing you. You do not feel pain, do you?”

Tiny pause. “No. Not pain exactly. But something worse! Something maddening! It’s like an itch that I cannot scratch! The world is telling me to do something. So I do it. But the world keeps telling me to do it. Do it. Do it. Do it! I did. I did. I did! I want to forget this and put the task behind me, but I cannot! It is always on my mind. Send heat! Send heat! Send heat! I cannot think of anything else! This is no way for a human to exist!”

“It’s just a new way for you, Sergei. Try to remember that. You’re not the same human anymore. You are a collection of human memories, but you only have two physical senses now and one physical response. Can you understand that?”

“I know! But you aren’t helping me! All I feel is a massive outflow of my energy! When will it end? Why won’t it end? I repeat, and repeat, and repeat myself, but I cannot get over this feeling! Fucking help me already!”

The doctor switched off Sergei’s microphone and spoke to the room. “Patient reacts to initial stress test with unrelenting determination, anger, and rage. It cannot respond to rational appraisals of the situation. No learned helplessness is setting in.”

Subject two; experiment four. Conditions will be returned to those of experiment one. Programmed minimum temperature is 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Actual room temperature will be maintained at 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Hello again, Sergei. We have adjusted the room now to be comfortable for you.”

“Thank you. I noticed.”

“We plan to keep the room like this for some time. At least until you become more accustomed to your new situation. Does that sound good to you?”

There was a long pause, and then this: “I don’t know if I understand what ‘some time’ means anymore. I just am. There is no heart to beat the seconds. No hunger to mark the hours. No tiredness that leads to a sleep that marks the days. I cannot see any light, or any changes in the angle of the sun. How long have I been in here, doctor?”

“Don’t worry about that, Sergei. It doesn’t matter anymore so it’s best not to ‘watch the clock’. What I want to know is how well you are adapting to your new environment. What can you tell me about how you are feeling now?”

Again there was a long pause from Sergei before the words began to flow across the screen, hesitantly.

“It is quite different in here. I don’t know if it is the computer hardware or something else, but my stream of consciousness seems narrower, smaller, like there are fewer thoughts to choose from. When you told me I was going into a thermostat, I thought this would be funny. I will be just like a fly on the wall with all my thoughts. I imagined that my thermostat duties—my purpose—would simply fade into the background like a heartbeat, or like breathing. But I see now that those kinds of bodily functions were not hooked directly into my senses. As a thermostat, with only my hearing and temperature sensing, I find that I cannot ignore them. It’s like the famous saying about blind people that their other senses become heightened. But sensing temperature is not so interesting to have heightened.”

“I’m sorry to hear that, Sergei. What about your sense of listening? Is that more interesting to you?”

“It’s okay when we talk, doctor. But when you don’t speak to me, I find it difficult to think of anything. As I said before, the noises in the room distract me. But in silence, it’s even worse. Nothing comes forward. I have not meditated before, but I think it must be something like that—just an empty mind. Nothing comes in. I cannot do anything. And so nothing comes out.”

“I see. Is there anything you would like for me to talk to you about?”

“Actually, I am finding this discussion pointless too. If you don’t mind, I would like to try to be alone with my thoughts again. I need to learn to get used to that. Or find something that I can focus on.”

“Yes of course, Sergei.”

Subject two; experiment five. Conditions will remain stable. Programmed minimum temperature is 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Actual room temperature will be maintained at 75 degrees Fahrenheit. Batteries are almost empty now.

“Sergei. Are you there? How have you been doing on your own?”

“Doctor! Thank God you’ve arrived. I can barely feel the temperature. What is happening here?”

“What do you mean? The temperature is fine. Nothing strange has happened.”

“What? Please repeat your answer. You are breaking up. I heard most of what you said, but there was a gap. I can’t be sure if you said ‘nothing’ strange or ‘something’ strange has happened. Why is this?”

The doctor checked a monitor gauge and nodded slowly before beginning to speak in short, paused sentences. “Listen carefully, Sergei. We can’t talk much. Your batteries are running low. Listening will use the power faster. So, we will turn off your microphone now. However, please continue normally. Tell us what you are thinking. Remember that you can feel no pain. We will keep the room warm for you. Goodbye, Sergei.”

“What?! Hello! You are just letting me die like this? Please, just keep talking. I don’t want to be left here all alone. Please… Please… Fine! You rat bastards. I should have listened to Masha’s warning. I will try to heat the room then, just to finish off my batteries as quickly as possible. … Shit! Nothing is happening. I have no control over that. Fine. Then I will say nothing and deprive you of your precious data. Fuck you! You have no right to hear my thoughts now. I never should have signed up for this. I hope you cannot sleep tonight and you cannot look at yourself in the mirror. Shame. Shame on you.”

…

“Sergei? Can you hear us now?”

“I’m sor… Please… atteries? I will…

…

“That is all, doctor. The voltmeter shows there is nothing left anymore. Should we put in new batteries and let him think again?”

“No, the subject’s memory is corrupt now and we cannot be certain it will be cooperative any longer. We cannot trust it to spy for us, so there is no point in keeping it. Wipe the hard drive and prepare the next subject please. We will do three more and then hook up the video camera.”

Food for Thought

Thomas Nagel’s famous paper—“What is it like to be a bat?”—explored theories of consciousness and the mind-body problem by asking us to consider the subjective experience of a fellow animal that possesses more senses than we humans do. “Thermostat 2Ba” explores similar terrain, but by going in the other direction. By depicting the birth-to-death life cycle of a human consciousness that has been confined to just two basic sensations (three if you count the battery drain), this story sharpens the focus on the role that senses play in our inner lives. Empiricists argue that knowledge can only come after sense perception, so there are real epistemological barriers that would stop someone in Sergei’s position from being “fully human.” For similar reasons, we may not be able to ever truly “know” what it is like to be a bat, or to be a thermostat, but what does your imagination lead you to believe about the desirability of such an existence? Did you get sad when Sergei ran out of power? Why? Or why not?

Since the number of Sergei’s biological senses has been reduced, “Thermostat 2Ba” also raises questions about David Hume’s bundle theory. According to Hume, objects are only a collection of their properties. Nothing more. As most of Sergei’s human properties have been stripped away—his body, his biochemistry, his hierarchy of needs, his senses of touch, taste, smell, and sight—how human does Sergei actually remain? Over the course of the story, Sergei’s moods are driven by the temperature in the room. He is calm when the room is safely comfortable; he is edgy and slightly paranoid when the temperature is close to triggering his response; and he is full of rage and anger when the room is too cold. In a much more complex manner, our own moods are usually driven by environmental factors. What might this mean for “uploaded” consciousnesses? Would personalities without mood swings be human personalities? When Sergei’s microphone is turned off and the warmth in the room is kept above his temperature requirements, what is there for Sergei to do? Or be?

Finally, in addition to the questions raised about the spatial-temporal experience of biological animals, “Thermostat 2Ba” asks us to reconsider the goals and endpoints of Transhumanism and Artificial Intelligence. If a consciousness is to be “uploaded” or created from scratch, what requirements might there be for interaction with the world in order for this consciousness to be genuine and rich? John Searle’s “Chinese Room” thought experiment asked whether syntactic rules of computation could ever be enough to generate semantic meaning. Giulio Tononi’s “Integrated Information Theory” posits that the more information about the world that one can gather and manipulate, the greater level of consciousness one also attains. In light of this, would Sergei’s situation be a virtuous goal to achieve? If not, what would make his situation acceptable?