Perhaps a better question...

Perhaps a better question... Okay, so let's see what he's come up with.

--------------------------------------------------

The humanoids of Galafray are in many ways just like us. Their sense perception, however, is very different.

For example, light reflected in the frequency range of the spectrum visible to humans is smelled by the Galafrains. What we see as blue, they sniff as citrus. Also, what we hear, they see. Beethoven's Ninth Symphony is for them a silent psychedelic light show of breathtaking beauty. The only things they hear are thoughts: their own and those of others. Taste is the preserve of the eyes. Their best art galleries are praised for their deliciousness.

They do not have the sense of touch, but they do have another sense we lack, called mulst. It detects movement and is perceived through the joints. It is as impossible for us to imagine mulst as it is for Galafrains to imagine touch.

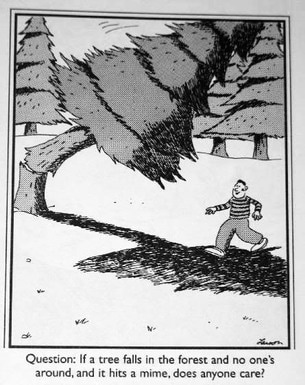

When humans first heard about this strange race, it did not take long for someone to ask: when a tree falls in a forest on Galafray, does it make a noise? At the same time, on Galafray they were asking: when a film is shown on Earth, does it make a smell?

Source: A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge by George Berkeley, 1710.

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 241.

---------------------------------------------------

So, Baggini has replaced a question about how one sense responds to the world with a question about how multiple senses might make sense of the same universe. That seems simple enough to solve for anyone with a perspective informed by evolutionary philosophy. But before we get to that, let's trace the history of this problem so we understand the context first.

As noted in the source citation above, the tree in the forest problem was first mentioned by the philosopher George Berkeley in A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge. In that book, he "largely seeks to refute the claims made by Berkeley's contemporary John Locke about the nature of human perception. Whilst, like all the Empiricist philosophers, both Locke and Berkeley agreed that we are having experiences, Berkeley sought to prove that the outside world (the world which causes the ideas one has within one's mind) is also composed solely of ideas."

In my brief blog post about George Berkeley, I noted that this strange view of the world was an inevitable attempt to solve the unsolved mind-body problem in a new way. Descartes had said the mind and the body were two separate and distinct types of things—i.e. dualism. Spinoza (and others) said these were both one material thing—i.e. monism. But Berkeley said these were all one thing, and they were all mind—i.e. idealism. To Berkeley, things only exist when they are perceived. This may sound ludicrous, but in section 23 of his Treatise, Berkeley preempted objections to this idea when he wrote:

‘But’, you say, ‘surely there is nothing easier than to imagine trees in a park, for instance, or books on a shelf, with nobody there to perceive them.’ I reply that this is indeed easy to imagine; but let us look into what happens when you imagine it. You form in your mind certain ideas that you call ‘books’ and ‘trees’, and at the same time you omit to form the idea of anyone who might perceive them. But while you are doing this, you perceive or think of them! So your thought-experiment misses the point; it shows only that you have the power of imagining or forming ideas in your mind; but it doesn’t show that you can conceive it possible for the objects of your thought to exist outside the mind. To show that, you would have to conceive them existing unconceived or unthought-of, which is an obvious contradiction. However hard we try to conceive the existence of external bodies, all we achieve is to contemplate our own ideas. The mind is misled into thinking that it can and does conceive bodies existing outside the mind or unthought-of because it pays no attention to itself, and so doesn’t notice that it contains or thinks of the things that it conceives. Think about it a little and you will see that what I am saying is plainly true; there is really no need for any of the other disproofs of the existence of material substance.

This is clever, which is why Berkeley has a place in history at all, but really he's just saying that you can never know what is happening when we aren't looking at something. When discussing the phantom possibilities of such trees in forests, Albert Einstein is reported to have asked his fellow physicist and friend Niels Bohr "whether he realistically believed that 'the moon does not exist if nobody is looking at it.' To this Bohr replied that however hard he (Einstein) may try, he would not be able to prove that it does, thus giving the entire riddle the status of a kind of an infallible conjecture—one that cannot be either proved or disproved."

Infallible? Yes. But only because it is completely unscientific by being unfalsifiable. There are, however, infinite such nonsenses, like Bertrand Russell's teapot orbiting the sun, the flying spaghetti monster, or all historical notions of God for that matter. As with all such cases, the burden of proof for such strange ideas must fall on the person advocating the notion, since such things cannot be disproven. But of course, Berkeley's tree winking in and out of existence has never received such proof. His disproof of materialism fails.

Later—once the original intention of this "hackneyed conundrum" was confined to the dustbin of fictional inventions—the problem of the tree in a forest morphed into a question that is easily answered by having clear definitions. For example, the word 'sound' historically referred "exclusively to an effect in the mind. Webster's 1947 dictionary defined sound as: "that which is heard; the effect which is produced by the vibration of a body affecting the ear." This meant (at least in 1947) the correct response to the question: "if a tree falls in the forest with no one to hear it fall, does it make a sound?" was "no". However, owing to contemporary usage, definitions of sound as a physical effect are prevalent in most dictionaries. Consequently, the answer to the same question is now "yes, a tree falling in the forest with no one to hear it fall does make a sound".

So, the same scientific definitions of cause and effect can be referred to for all possible senses, and they must take into account the evolutionary history of any creature sensing its environment. If some long-ago, proto-Galafrain, multi-celled organism first produced chemical reactions in response to light waves, and that eventually led to blue light "tasting" the same to them as the organic compounds that exist in our citrus fruits, then yes, things that we humans "see" could be "smelled" by Galafrains, as long as we are clear whose senses we are talking about. From our current perspective, such Galafrains may seem to have an odd and overly complicated way of adapting to one's environment, but maybe our own sensory perceptions are more strange than we realise. We won't really know that until we can travel somewhere like the seven new exo-planets discovered this week and find new forms of life that do not share our evolutionary history. Until then, we'll just have to confine these sci-fi imaginings to the material world of our minds.

What do you think? Can you hear what I'm saying?