Writers may be classified as meteors, planets, and fixed stars. A meteor makes a striking effect for a moment. You look up and cry “There!” and it is gone forever. Planets last a much longer time. They often outshine the fixed stars and are confounded by them by the inexperienced; but this only because they are near. It is not long before they must yield their place; nay, the light they give is reflected only, and the sphere of their influence is confined to their orbit — their contemporaries. Their path is one of change and movement, and with the circuit of a few years their tale is told. Fixed stars are the only ones that are constant; their position in the firmament is secure; they shine with a light of their own; their effect today is the same as it was yesterday, because, having no parallax, their appearance does not alter with a difference in our standpoint. They belong not to one system, one nation only, but to the universe. And just because they are so very far away, it is usually many years before their light is visible to the inhabitants of this earth.

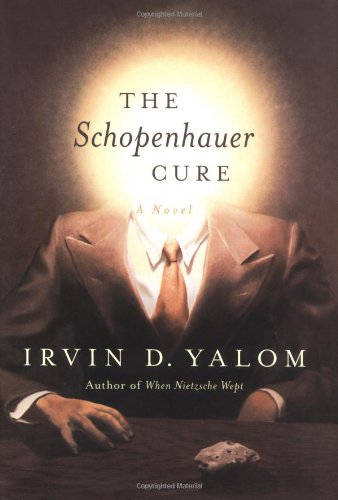

We'll see a little later whether Schopenhauer himself reached the status of a fixed star, but there's another writer alive today who's a real favorite of mine to become a star and who happens to have written a novel that does a fantastic job introducing readers to the philosophies of this 19th century German. That novel is The Schopenhauer Cure by Irvin Yalom. Yalom is an existential psychotherapist in San Francisco who wrote a wonderful non-fiction book about the kinds of cases he deals with in his practice (Love's Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy), as well as an astounding piece of historical fiction (When Nietzsche Wept) that imagined Nietzsche discussing his personal problems with Sigmund Freud's mentor, and a founder of psychotherapy, Joseph Breuer. Those two books are among my most influential, and although The Schopenhauer Cure didn't quite speak to me at the same height, it is still better than almost anything else being published these days. Re-reading the detailed description of the book below makes me want to try it again to see if maybe I've changed enough to get something more out of it. See if this grabs you too.

At one time or another, all of us have wondered what we'd do in the face of death. Suddenly confronted with his own mortality after a routine checkup, distinguished psychotherapist Julius Hertzfeld is forced to reexamine his life and work. Has he really made an enduring difference in the lives of his patients? And what about the patients he's failed? What has happened to them? Now that he is wiser and riper, can he rescue them yet?

Reaching beyond the safety of his thriving San Francisco practice, Julius feels compelled to seek out Philip Slate, whom he treated for sex addiction some twenty-three years earlier. At that time, Philip's only means of connecting to humans was through brief sexual interludes with countless women, and Julius's therapy did not change that. He meets with Philip, who claims to have cured himself -- by reading the pessimistic and misanthropic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer.

Much to Julius's surprise, Philip has become a philosophical counselor and requests that Julius provide him with the supervisory hours he needs to obtain a license to practice. In return, Philip offers to tutor Julius in the work of Schopenhauer. Julius hesitates. How can Philip possibly become a therapist? He is still the same arrogant, uncaring, self-absorbed person he had always been. In fact, in every way he resembles his mentor, Schopenhauer. But eventually they strike a Faustian bargain: Julius agrees to supervise Philip, provided that Philip first joins his therapy group. Julius is hoping that six months with the group will address Philip's misanthropy and that by being part of a circle of fellow patients, he will develop the relationship skills necessary to become a therapist.

Philip enters the group, but he is more interested in educating the members in Schopenhauer's philosophy -- which he claims is all the therapy anyone should need -- than he is in their individual problems. Soon Julius and Philip, using very different therapeutic approaches, are competing for the hearts and minds of the group members.

Is this going to be Julius's swan song -- a splintered group and years of good work down the drain? Or will all the members, including Philip, find a way to rise to the occasion that brings with it the potential for extraordinary change? In The Schopenhauer Cure, Irvin Yalom elegantly weaves the true story of Schopenhauer's psychological life throughout the narrative, knitting together fact and fiction to form a compellingly readable tale.

Talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see.

Life is short and truth works far and lives long: let us speak the truth.

It is the courage to make a clean breast of it in the face of every question that makes the philosopher.

To be a philosopher, that is to say, a lover of wisdom (for wisdom is nothing but truth), it is not enough for a man to love truth, in so far as it is compatible with his own interest, with the will of his superiors, with the dogmas of the church, or with the prejudices and tastes of his contemporaries; so long as he rests content with this position, he is only a philantos, not a philosophos [a lover of ego, not a lover of wisdom].

No doubt, when modesty was made a virtue, it was a very advantageous thing for the fools, for everybody is expected to speak of himself as if he were one.

A reproach can only hurt if it hits the mark. Whoever knows that he does not deserve a reproach can treat it with contempt.

The chief sign that a man has any nobility in his character is the little pleasure he takes in others’ company. What now on the other hand makes people sociable is their incapacity to endure solitude and thus themselves.

Wealth is like sea-water; the more we drink, the thirstier we become.

The chief objection that I have to Pantheism is that it says nothing. To call the world "God" is not to explain it; it is only to enrich our language with a superfluous synonym for the word "world".

The bad thing about religions is that instead of being able to confess their allegorical nature, they have to conceal it.

There are two kinds of authors: those who write for the subject’s sake, and those who write for writing’s sake. The first kind have had thoughts or experiences which seem to them worth communicating, while the second kind need money and consequently write for money.

For a work to become immortal it must possess so many excellences that it will not be easy to find a man who understands and values them all; so that there will be in all ages men who recognise and appreciate some of these excellences; by this means the credit of the work will be retained throughout the long course of centuries and ever-changing interests, for, as it is appreciated first in this sense, then in that, the interest is never exhausted.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860 CE) was a German philosopher known for his pessimism and philosophical clarity. Schopenhauer's metaphysical analysis of will, his views on human motivation and desire, and his aphoristic writing style influenced many well-known thinkers.

Survives

Schopenhauer refused to conceive of love as either trifling or accidental, but rather understood it to be an immensely powerful force lying unseen within man's psyche and dramatically shaping the world. These ideas foreshadowed Darwin’s discovery of evolution, Freud’s concepts of the libido and the unconscious mind, and evolutionary psychology in general. Love, in its many forms, is one of the primary emotions we use to propagate the species and cooperate with each other for its long-term survival. It is immensely powerful.

Needs to Adapt

Gone Extinct

Schopenhauer believed that humans were motivated only by their own basic desires, or Will to Live, which directed all of mankind. For Schopenhauer, human desire was futile, illogical, directionless, and, by extension, so was all human action in the world. For Schopenhauer, human desiring, willing, and craving cause suffering or pain. He therefore favored a lifestyle of negating human desires, similar to the teachings of ancient Greek Stoic philosophers, Buddhism, and Vedanta. But suppressing our desires leads to the death of the species! Striving for life is not futile. The direction is towards immortality for the species. We merely struggle with balancing short-term desires and long-term needs.

A temporary way to escape the pain of life is through aesthetic contemplation since art diverts the spectator's attention from the grave everyday world and lifts him or her into a world that consists of mere play of images. This is the next best way, short of not willing at all, which is the best way. Escapism leads to stagnation and the extinction of the species. Art should instead be used to motivate the species. It is most powerful when it does this.

Schopenhauer's moral theory proposed three primary moral incentives: compassion, malice and egoism. Compassion is the major motivator to moral expression. Malice and egoism are corrupt alternatives. Survival is the major motivator to moral expression. Egoism is feeling positive towards yourself. You are alive. This is worth celebrating and encouraging. Malice and compassion are negative and positive feelings towards others. They have their roles in a cooperative society that follows the tit for tat strategy to punish cheaters and remain stable over the long-term.

Schopenhauer described himself as a proponent of limited government. He shared the view of Thomas Hobbes on the necessity of the state, and of state violence, to check the destructive tendencies innate to our species, but what he thought was essential was that the state should "leave each man free to work out his own salvation.” And so long as government was thus limited, Schopenhauer preferred "to be ruled by a lion than one of his fellow rats" - i.e., by a monarch, rather than a democrat. An unelected monarchy is much more likely to produce a rat than a democratic election conducted by an educated population.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

For someone as pessimistic about humanity as Schopenhauer was, and who believed the universe to be a fundamentally irrational place, is it any wonder that his thoughts ended up different than mine? To me, observing the actions of life trying to stay alive make the world make sense. Sometimes, organisms make poor choices for the long term, but they are usually understood from the perspective of the individual or their narrow interests. Surrounded by nearsightedness, I admit I often give in to feelings of Schopenhauer's pessimism, but it usually only takes a few moments of gazing at the fixed stars of our best writers in human history to remind me of the progress we are making. For them, I say thanks, and I'll do my best to join your ranks some day.