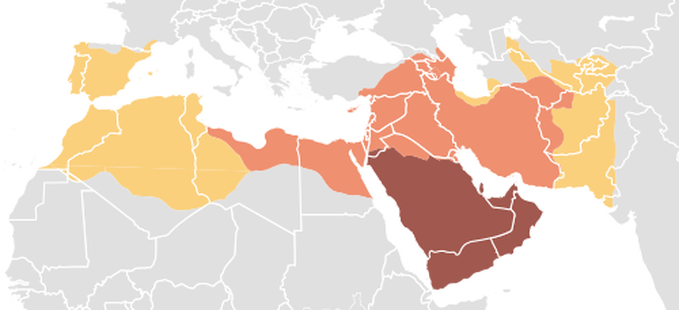

Last week, I looked at the soundness of Muhammad's teachings and found them severely lacking. What cannot be argued, however, is that they were effective. After his death in 632, proceeding leaders of the Islamic faith spread the word of their prophet and were unafraid to use the method of jihad to "struggle in the way of Allah" and build larger and larger caliphates, expanding first throughout the Arabian Peninsula, then along the Persian Gulf as well as the Mediterranean, Red, and Caspian Seas, before stretching out all the way from Portugal to India. While the collapse of Rome left Europe groping in the dark ages, this new empire to the south enjoyed several hundred years known as Islam's Golden Age during which time the extensive texts of the Greco-Roman, Persian, and Indian civilisations were encountered, translated into arabic, and studied extensively. The spread of this knowledge was aided tremendously by the concurrent spread of the invention of paper. While the Chinese had been using paper since they invented it in 105 CE, it did not move to the West until the defeat of the Chinese in the Battle of Talas in 751CE in present day Kyrgyzstan at the border between these two major empires. In the Muslim world, with a "new, easier writing system and the introduction of paper, information was democratized to the extent that, probably for the first time in history, it became possible to make a living from simply writing and selling books." (I wish that were easier today!) The whole of the Middle East along the silk road came to provide a thriving atmosphere for scholarly and cultural development. Into this world, in 980 CE, near the centre of present day Uzbekistan, in the city of Bukhara (which rivalled Baghdad as a cultural capital of the Islamic world), the great Avicenna was born—the most famous philosopher of the Islamic Golden Age.

| Avicenna's father was a respected Islamic scholar and he had his son very carefully educated at Bukhara where "his independent thought was served by an extraordinary intelligence and memory, which allowed him to overtake his teachers at the age of fourteen. As he said in his autobiography, there was nothing that he had not learned when he reached eighteen" (which is a bit modern in its teenage know-it-all-ness, isn't it). Fortunately, Avicenna didn't stop learning at 18 and went on to create an extensive body of work. He wrote almost 450 works on a wide | The great city of Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Birthplace of Avicenna. |

An ignorant doctor is the aide-de-camp of death.

Unfortunately, so is an ignorant philosopher, as we have seen repeatedly throughout this series in my examination of the Survival of the Fittest Philosophers. Avicenna was less destructive than most medieval philosophers, and although that's not saying much, let's see exactly what he had to say.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Avicenna (980-1037 CE) was a Persian polymath who wrote almost 450 treatises on a wide range of subjects. His corpus includes writing on philosophy, astronomy, alchemy, geology, psychology, Islamic theology, logic, mathematics, physics, as well as poetry. He is regarded as the most famous and influential polymath of the Islamic Golden Age in which the translations of Greco-Roman, Persian, and Indian texts were studied extensively.

Survives

His 14-volume Canon of Medicine was a standard medical text in Europe and the Islamic world until the 18th century. The book is known for its description of contagious diseases and sexually transmitted diseases, quarantine to limit the spread of infectious diseases, and testing of medicines. Some nice contributions to the long lineage of medical science.

Needs to Adapt

Avicenna inquired into the question of being (metaphysics), in which he distinguished between essence and existence. He argued that the fact of existence cannot be inferred from or accounted for by the essence of existing things, and that form and matter by themselves cannot interact and originate the movement of the universe or the progressive actualization of existing things. Existence must, therefore, be due to an agent-cause that necessitates, imparts, gives, or adds existence to an essence. It is still not known what caused the origin of the universe or why matter exists at all. However, it is well known how form and matter interacted to create the progressive actualization of existing things—this is evolution. The infinite regression of the agent-cause argument (who created the first agent?) leads only to the same questions. It does not lead to an all-seeing god.

Gone Extinct

Avicenna wrote his famous "Floating Man" thought experiment to demonstrate human self-awareness and the substantiality and immateriality of the soul. He told readers to imagine themselves created all at once while suspended in the air, isolated from all sensations, which includes no sensory contact with even their own bodies. He argued that, in this scenario, one would still have self-consciousness. The first knowledge of the flying person would be “I am,” affirming his or her essence. That essence could not be the body, obviously, as the flying person has no sensation. Avicenna thus concluded that the idea of the self is not logically dependent on any physical thing, and that the soul should not be seen in relative terms. The body is unnecessary; the soul is an immaterial substance. But bodies cannot just appear all at once suspended in air and isolated from all sensations. The argument is false right from the start. Our bodies are grounded in reality and there are no souls.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Not a particularly big contribution to the progress of philosophy, but we are indebted to Avicenna for his role in keeping inquiry alive during the dark ages. It won't be surprising in a few weeks to see the Islamic Golden Age come to an end though, moving on through one more bright light before the torch is passed to a revived Western Europe. Unfortunately, we haven't reached the light at the end of this dark tunnel just yet.