I say "yet another attack from a potential ally" for three reasons. The first is that a recent book published by the team at The Philosopher--Philosophy in the Borders by Michael Bavidge—contained an essay titled "Humanism: What’s Not to Like?", which made pointed cases for four things not to like. My second reason is to refer to a recent exchange of letters between the historian (and author of Sapiens) Yuval Harari, and the philosopher (and prominent American Humanist) Andy Norman, which was published in Free Inqury under the title, "The Meaning And Legacy Of Humanism: A Sharp Challenge From A Potential Ally." And finally, I want to emphasize this point of potential allies because I too would critique fellow Humanists with several of these challenges if they were indeed accurate.

Therein lies the rub, however. All of these broadsides have been leveled at "humanism" as if it were one clear set of philosophical principles or beliefs. But that's just not the case. As one of North East Humanists' committee members said to me recently, "Trying to define humanism is like trying to nail jelly to a wall." Here, for example, are some of the attempts at this in the articles listed above:

- In Morgan's book review, he admits that, "Even after a fair amount of research, it remains unclear to me precisely what humanism is, and what it aspires to be."

- Bavidge begins his (purposefully short and provocative) polemic by saying far too broadly that, "Humanism is the default ideology of Western liberal democracies."

- Harari and Norman went much deeper in their exploration of the term. Norman began by saying, "Contemporary humanism, as articulated in several humanist 'manifestos,' is the product of decades of intellectual and social toil."

- To this, Harari said, "By the term humanism you seem to refer to the twentieth-century humanist movement that goes back to the Humanist Manifesto of 1933. In contrast, I use the term to refer to a much wider historical current, which goes back at least to the late medieval and early modern Italian humanists (for instance, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola’s “Oration on the Dignity of Man” from 1486). In this broader sense, “humanism” refers to the epochal shift in authority from God and scripture to humanity—and in particular to human reason and human feelings. I would succinctly define humanism as “the belief that human feelings are the supreme source of authority—whether in politics, economics, ethics or art. ... This broad understanding of humanism is not some new invention of mine, but something that is very common among historians in general."

- To this, Norman admitted: "I’m compelled to concede that you have grounds for using the term humanism as you do. It’s true that academics have used the term to designate a broad cultural current with roots in the Renaissance and antiquity, and I’ll grant that that is precedent enough to give you the right to use humanism in roughly the way you do." [But] "the term humanism has developed a new and salutary set of uses. ... Hundreds of thousands of well-meaning progressive reformers have since found a sustaining and motivating identity in humanism. And here’s the point: this too is part of the history of humanism. This new usage extends far beyond a small circle of academic historians—it’s out there in the world, shaping people, movements, and trends. Given that the term has acquired these uses, you can’t responsibly characterize humanists as advocating the blind worship of humanity. To do so is to caricature."

So, before responding to some of the particular critiques levelled against humanism, let's set out some definitions to make it clear what we are talking about here. First, there is a very basic distinction that can be made.

humanism vs. Humanism — Both Humanists International and the American Humanist Association have essays on their websites calling for any discussions of the Humanist movement to be capitalized, but this has not (yet) become a widespread convention. They say, "We use initial capitals for the religious life stances, Hinduism, Christianity etc; why discriminate against Humanism?" Also, we ought to "insist upon the distinction between Humanism (capital H), as developed by the organized Humanist movement, and humanism (small h), as professed by individuals and organizations outside of that movement." This helps set the usage of Humanism "against 'renaissance humanism', on the one hand, and a generalized 'concern for humanity’ on the other." To me, even though it's an open question whether Humanism is a religious life stance, we can also capitalize it in the way that citizens in a representatively-governed country are called democrats, while members of Barack Obama's political party are referred to as Democrats.

How does this track with the essays we are considering here? Morgan uses humanism (except when he invents a Cheerful Humanist to skewer), although he mixes his targets between the specific movement and the general idea. Tallis uses humanism in his writings but is a patron of a Humanist organization. Bavidge uses Humanism and purposefully tries to target the movement, although he too lumps it together with the older idea. Harari uses humanism for his critiques but says he finds the movement laudable. And Norman uses humanism although he is defending the Humanist movement.

For me, I have nothing more to say here about humanism. You can look to historians for more on that. As a trustee of North East Humanists, however, I have been exposed to more information than most about Humanism, and I would like to draw on this experience to defend it. To begin, a little history of Humanism helps. In a brochure I recently produced for NEH, I noted:

Humanist ideas and philosophies have been around pretty much since there were humans. From the beginning of recorded history, there have been people who believed that this life is all we have, and it is up to us to make the most of it, rather than waiting for any supernatural intervention to come along. ... Starting in the late 19th century, people who subscribed to this worldview began to form official groups to support one another and act for the betterment of society. This “ethical movement” (as it was called then) slowly evolved into the various Humanist organizations we see today at the local, national, and international levels. The United Kingdom was one of the earliest locations for this movement, and Humanists UK can trace its origins back to 1896. Later, in 1952, they were one of the first five groups to start Humanists International (as it is known today). At our local level, secularism was active in the north of England since the 1860’s but was officially organized in 1957 into what is today the North East Humanists. That makes NEH one of the oldest regional humanist groups in the United Kingdom, and it is currently the largest such group too.

There are literally hundreds of Humanist organizations now at local, national, and international levels. Many of them form partnerships and support one another, but there is no universal governing body or controlling hierarchy. As you might expect from such a situation, there are, therefore, many and diverse definitions of Humanism. The fullest definition to have a measure of international agreement, however, is contained in the Amsterdam Declaration of 2002 from Humanists International. That is worth a quick read, and I will cite from it later, but for now, here are some other more concise definitions:

- Humanism is a democratic and ethical life stance that affirms that human beings have the right and responsibility to give meaning and shape to their own lives. Humanism stands for the building of a more humane society through an ethics based on human and other natural values in a spirit of reason and free inquiry through human capabilities. Humanism is not theistic, and it does not accept supernatural views of reality. —The Minimum Statement on Humanism, Humanists International

- Humanism is the belief that we can live good lives without religious or superstitious belief. Humanists make sense of life using reason, experience, and shared human values. We seek to make the best of the one life we have by creating meaning and purpose for ourselves. We take responsibility for our own actions and work with others for the common good. —Humanists UK, 2003

- Humanism is a progressive philosophy of life that, without theism or other supernatural beliefs, affirms our ability and responsibility to lead ethical lives of personal fulfillment that aspire to the greater good. —American Humanist Association

Humanists UK have produced a free 6-week online course called Introducing Humanism that goes into much more detail about all of this. I'll be citing from that—and from the plentiful amounts of other Humanist information out there—when I respond to individual critiques of Humanism, but there is one more important point to make about Humanism before I get to that. As you may have noticed in the definitions above, Humanism has a very decentralized view of morality, meaning, and purpose. It tends to emphasize democracy, personal responsibility for one's own life, and an ever-changing progressive view of the world. This is radically different than the unchanging dogma of religious worldviews, but it is also what makes finding a precise philosophical definition for Humanism so difficult—there just isn't any precision there. Humanists recognize they don't have all the answers that would give them what the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss called an Ultimate Philosophy. (No one has these answers, by the way. To think you do is like claiming you can blow a balloon up from the inside.)

Næss, the founder of the Deep Ecology movement, described four levels of organization for the questioning and articulation of total views: 1) Ultimate Philosophies; 2) Platform Principles of Movements; 3) Policies; and 4) Practical Actions. Næss put his Deep Ecology at level 2, which allows followers of many different level 1 philosophies (e.g. Christians, Buddhists, etc., or his own personal worldview called Ecosophy T) to all still join the Deep Ecology movement. I would say that Humanism fits in level 2 in this conception too. Humanism creates a big tent for people to join by agreeing to a broad methodology or approach to life. But there are still many different ultimate conclusions that can be drawn from this approach, and Humanists are humble enough to recognize this.

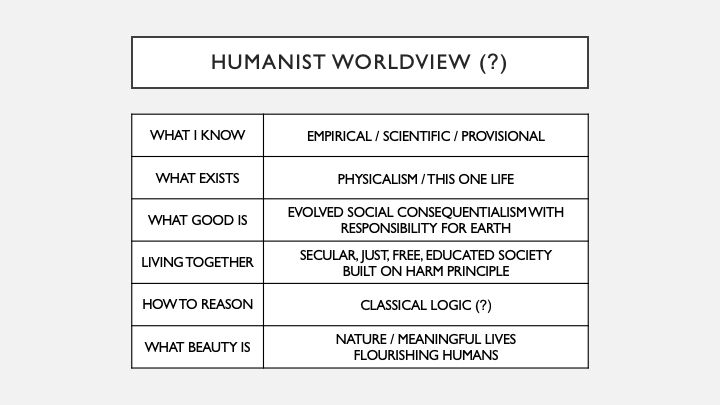

To get more philosophically precise about this, I have defined worldviews in my work as the sum total of one's positions in the six major branches of philosophy. In a talk I gave to North East Humanists last year, I said a Humanist worldview might, therefore, look something like this:

With all of that work done to define Humanism generally, it becomes much easier to address specific criticisms of humanism. To do that, let's go from the oldest to the newest. This also takes us from the easiest to respond to (Harari in 2018) to the one that takes the most work (Morgan/Tallis in 2020). Let the defense begin!

***

As discussed above, Yuval Harari leveled many claims against humanism in his 2015 book Sapiens. He said that the crimes of genocidal Nazism, Stalinist communism, and environmental destruction could all be traced to the central tenets of humanism. This is already a very poorly argued claim against humanism (which Norman did well to point out), but it has no bearing whatsoever on Humanism, so I won't address that here. Harari does, however, raise two important questions for Humanism in his exchange with Norman, so let me summarize them and offer my responses.

Question 1 from Harari

Just as theism thinks authority comes from theos (god), and nationalism thinks authority comes from the nation, so humanism believes that authority comes from humanity. That’s why it is called humanism. Perhaps secular humanism does not sanctify humanity at all and instead sees authority as inherent in science, in which case, why call it humanism and not scientism?

Response to Question 1

Harari is trying to infer something about Humanism that isn't there. Theism and nationalism may define themselves in relation to the authority of their nominal leading entities, but Humanism rejects such authority. Humanists literally see no author who could philosophically give orders, make decisions, and enforce obedience. Norman notes that science deals with facts and not values, so the name scientism doesn't work for this. He prefers rationalism but notes that it's hard to rebrand a movement mid-stream. I would argue that rationalism has a specific meaning in philosophy that is opposed to empiricism so that brand name doesn't work either. I agree it's hard for many people to get past the first two syllables of Humanism when trying to understand it, but I think the name works to acknowledge the real limitations we have as human beings. We can't know or feel what (if anything) other natural or supernatural beings know or feel. So, what else could we subscribe to? To me, the name has a "humanism, all too humanism" ring to it. That leads directly to Harari's next challenge.

Question 2 from Harari

How does humanism relate to post-humanism? Given the emphasis on science, reason, and human enhancement, what does humanism think about the possibility of using biotechnology to create superhumans or using computer science to create super-intelligent AI? What possible objections could humanism have to the creation of superhumans and AI and to transferring authority to such entities?

Response to Question 2

Again, Humanism rejects cosmic authority, so there's no worry about ceding it or transferring it. Transhumans or AI may someday offer more perspectives on what exists and how we ought to live, but the path there is fraught with existential risk that needs to be navigated first. If a world with beyond-human-intelligent beings ever comes, maybe they'll be smart enough to finally give us a better name to run with than Humanism.

***

Our next witness to cross-examine is Michael Bavidge whose book Philosophy in the Borders contained an essay titled "Humanism: What’s Not to Like?" Bavidge is now a retired philosophy teacher from Newcastle University who tells us elsewhere in his book that he left a seminary decades ago but is now an atheist. From those brief personal facts, he seems a likely candidate to be a Humanist, but his essay lists four things not to like about the group which must be keeping him away.

Dislike 1 from Bavidge

Humanism puts humanity at the centre of things; but we are not up to it. ... The Enlightenment shift from a theocentric to an anthropocentric view of life takes God out of the picture and put humanity in his place. ... One place where the poverty of this attitude emerges is in Humanism's species-selfishness, in the failure of Humanism to give a plausible account of ecological values and animal welfare. In recent years, Humanist literature has tacked on a concern for the natural world but it is a jerry-built lean-to on the side of the Humanist 18th century country house.

Response to Dislike 1

This is a common misconception about Humanism—that it worships humans and puts them above all else—but it is absolutely wrong. This is something that even some Humanists get wrong, though, so I understand where Bavidge is coming from and I would join him in disliking any individual examples of it. In fact, Humanist magazine published a long essay I wrote about this called When the Human in Humanism Isn't Enough. The editor thought enough of it to make it a cover story for one of its issues. Don't just take my word on this topic though. In section §1.13 of the Humanist UK MOOC, there was this:

Humanism does not seek to glorify humanity. It makes no claims about our essential goodness, or about the inevitability of progress and the triumph of reason. Human beings are capable of great ignorance and cruelty, and one does not have to look hard to find examples of humanity at its worst. Humanism involves a realistic recognition of both our flaws and limitations, and our capacities, and asks us then to consider how we can make the best of our potential.

And as Norman said in his exchange with Harari:

Please look up any of the humanist manifestos and see if you can find any reference to the worship of humanity. You won’t find it because it isn’t there. I invite you to immerse yourself in the humanist literature. Humanists have been extremely clear: we think it’s a really bad idea to declare anything sacred and then harbor worshipful attitudes toward it. ... We want to tear down the pedestal, not climb atop it.

As for the supposed lack of ecological values, Bavidge just hasn't seen it, or he is too quick to dismiss it as something "built on the side of 18th Century humanism," which fails to recognize the fact that Humanism holds its changing nature as central to its identity. Once again, the Humanist UK MOOC rebuts Bavidge; this time with section §4.17, which notes:

Most humanists believe that our choices about how to act must take into account the impact on non-human animals. ... A humanist might argue that a morality that attempts to prioritize welfare, and tries to base itself on reason, evidence, experience, and empathy, will include an unwillingness to cause animals unnecessary suffering. ... The relevant question, for many humanists, is the one raised by Jeremy Bentham: Can non-human animals suffer?

The Amsterdam Declaration of 2002 has also moved Humanism in this direction with its fourth article:

4. Humanism insists that personal liberty must be combined with social responsibility. Humanism ventures to build a world on the idea of the free person responsible to society, and recognizes our dependence on and responsibility for the natural world.

Norman takes this even further in his exchange with Harari by noting:

Humanistic thinkers such as Jeremy Bentham and Peter Singer laid the foundations for the animal-rights and environmental movements. ... The industrial farming of animals, for example, is better explained as a consequence of population growth, greed, and unfettered markets. ... Exploitative attitudes toward the environment and convenient excuses for pillaging predate humanism by tens of thousands of years. Humanity didn’t need the philosophy of humanism to begin privileging itself. ... Early Humanist Manifestos contain some unfortunate, species-centric language. ... But here’s the neat thing about humanism: it’s self-revising. As a rule, humanists take critical challenges seriously and revise their thinking. We don’t treat our manifestoes as gospel; we work and re-work them. ... Humanist manifestos get superseded every few decades. (Compare that to the way religions cling to sacred scripture for millennia!) ... The most recent manifesto--Humanist Manifesto III—hints that we need to extend our moral concern “to the global ecosystem and beyond.”

Dislike 2 from Bavidge

Humanism is closely connected to Secularism which misunderstands religious belief and misrepresents its social impact. ... Secularism is the rejection of religious ways of life. It rejects appeals to religious or transcendent realities as explanations of anything, or as any sort of authority in moral political matters.

Response to Dislike 2

Bavidge is right that almost all Humanists are secularists, but he misunderstands what that means for religious belief in society. For example, I attended the Humanist UK annual conference in 2018 where a Muslim woman gave a talk saying she was grateful for the UK's secular laws which allowed her to worship her god in this legally Christian nation. Secularism does not try to stamp out religion; it carves out space where otherwise irreconcilable religions can coexist. As sections §5.3, §5.7, and §5.8 of the Humanist UK MOOC say:

Secularism is the idea that religious institutions should be separate from state institutions; that if we are to have equal citizenship in a shared society then we need a state that treats us neutrally. ... Secularism as an approach is one that tries to maximize people's freedom of belief. ... Not everyone can be free to do exactly what they want at all times, however. It’s important to draw a limit around freedom of religion and belief. For example, when it starts interfering with other people's rights and freedoms. ... The case for secularism is quite simple, and is built on three main pillars: the argument for freedom; the argument for fairness; and the pragmatic argument, or peace argument. ... Only in a secular state, in a state that doesn’t try to tell you what to believe or what to do or how you have to live, can people really have the freedom that they need.

Bavidge is right that this means "appeals to religious or transcendent realities as explanations of anything" are rejected. But this is true wherever evidence for something is lacking. Removing that requirement for argumentation would mean it is no longer argumentation.

Dislike 3 from Bavidge

Humanism has a problem with diversity. ... [For example, the Yanomami] Society has survived for thousands of years in the Amazonian jungle. It is built around a culture which is at odds with articles 2 and 5 of the North East Humanist’s manifesto. ... To bring it closer to home: how does protection of the Yanomami fit with opposition to faith schools? The danger is that Humanists end up intolerant of dissidents within their own societies, and paternalistic (at best) to societies with a radically different form of life. … Religious tolerance needs to be defended against Humanist intolerance.

Response to Dislike 3

Once again, Humanism and secularism are not trying to stamp out religions. Certainly not with force anyway. Humanist opposition to faith schools is not an opposition to faiths themselves, but to the public funding of discriminatory schools, and to schools that do not adhere to the existing laws for safeguarding and instructing children. Humanists have no issue with well run privately-funded faith schools. This is described in the fourth article of the Amsterdam Declaration of 2002:

4. Humanism insists that personal liberty must be combined with social responsibility. Humanism ventures to build a world on the idea of the free person responsible to society, and recognizes our dependence on and responsibility for the natural world. Humanism is undogmatic, imposing no creed upon its adherents. It is thus committed to education free from indoctrination.

Humanists may themselves not believe in religion, but Humanism's emphasis on freedom and personal responsibility for one's own life are completely in line with religious tolerance. But only up to the point where religious beliefs become intolerant themselves. This is the "intolerance of intolerance" that is required of all cosmopolitan societies. It is described in the first article of the Amsterdam Declaration of 2002:

1. Humanism is ethical. It affirms the worth, dignity and autonomy of the individual and the right of every human being to the greatest possible freedom compatible with the rights of others.

Section §5.11 of the Humanist UK MOOC also discusses this explicitly:

What do humanists think about religion? Drawing a distinction between the people who identify with a religion (e.g. Catholics), the religion itself (Catholicism), and the associated institutions (the Catholic Church) can help us when considering this question. ... Respecting the person doesn’t necessarily require a respect for the religion itself. ... Tolerance and respect also do not mean one cannot challenge and criticize opposing belief. ... Many humanists, however, are less hostile towards religion. Some may feel a cultural affinity towards it, or a fondness for its art, music, rituals, or its sense of community. Others may find it of historical and anthropological interest. Many will, while believing religious beliefs are mistaken, accept that there are many good people who are religious and many who can be motivated by their faith to do good things.

Since Bavidge named articles 2 and 5 from the North East Humanists' "manifesto" (in scare-quotes because we don't actually call it that and no one made me swear to it when I joined), let's see what they are and whether they are actually objectionable in regards to the Yanomami.

2. The universe has evolved over eons, without a creator or a plan. Humanists believe that human beings are part of an evolutionary process that began billions of years ago, and that there is no god or gods behind this process.

5. Democratic values take precedence over ideologies. Humanists are committed to a secular society. Whilst generally respecting the right of others to have different beliefs, Humanists challenge those beliefs and ideas which threaten the freedom of the individual.

These articles are defensible in every realm where scientific facts are admitted, and in all but the most relative or nihilist conceptions of morality. As long as the Yanomami do not infringe on the freedoms of those in secular societies, they may believe whatever they want and not be at odds with Humanists.

Dislike 4 from Bavidge

Humanism has an unhealthy relationship with the sciences. ... The underlying idea that ought to be resisted is that science is co-extensive with knowledge; that scientific methodologies are the only roads to knowledge, and that we can hope for a comprehensive view of the world and ourselves from the development of the sciences which supplant earlier attempts to understand in terms of religions, myth, and common sense.

Response to Dislike 4

The scientific method—broadly construed as a cycle of observations, hypotheses, and testing—does generate views of the world that have supplanted all sorts of "religions, myths, and common sense." Even so, Humanists do not as a rule have an unhealthy obsession with this. Section §2.16 of the Humanist UK MOOC explains:

Some critics accuse Humanists of scientism. Scientism can be defined in a number of ways, but it is often described as something like a ‘worship of science’, a belief that science can answer all our questions, or that science provides the only way to understand human beings and the world. Typically, however, humanists will not go so far. ... Many humanists accept that there are meaningful questions that lie beyond the remit of science. ... Firstly there are those questions that look for meanings or purposes behind things, e.g. questions around why the universe exists, or why it is the way it is, or questions about the purpose of our existence. Some people describe these as ‘ultimate’ questions, beyond the realm of science. ... Then there are moral questions: questions about how we should behave and how we should treat other people.

Humanists recognize the need for philosophy. And that brings us to the criticisms in The Philosopher.

***

The final defense of Humanism that I'll offer here is against the 6-pronged attack that Morgan leveled with the help of Tallis in his article "The Future of Humanism." Far from describing a future for the movement, this article misrepresents its past and present, while suggesting patently non-Humanist ideas are a requirement to go forward. Unfortunately, this prolonged attack is over 5,000 words so it requires a lengthy defense. Let's take Morgan's critiques one at a time though, starting with each headline, considering its justification, and then following with my response.

Critique 1 from Morgan / Tallis

1. Humanism lacks profundity.

On the opening page of Seeing Ourselves, secular humanist and patron of Humanists UK Raymond Tallis writes: “Humanism, for all its virtues, still lacks a philosophy that can compete in profundity with the religious beliefs it aims to displace.”

Humanism could thus be defined as the ethical wing of naturalism. The main problem with this, however, is that when naturalism extends its focus to that most perverse of natural objects, the human, the results are rather dispiriting.

Even in his analysis of gratitude, love, art, and philosophy as “secular sources of salvation” through which “we might palliate secular despair”, Tallis frequently finds humanist options falling short of their religious counterparts.

Tallis considers the respective virtues of romantic love and parental love, but ultimately concludes that they are both inadequate substitutes for the love of God that is “not only absolute but unchanging.”

The humanist attempt to recreate the traditional Christian Sunday service testifies to their desire for community. However, it is unclear that there are many things less appealing than sitting in a chilly community centre listening to sermons extracted from Grayling’s The Good Book and singing along to Oasis songs in a room full of spiritually malnourished humanists.

Response to Critique 1

First, it is not clear that religions are actually profound. Believers are racked with doubts. The descriptions of their gods have changed throughout history, and divine love is often questioned in times of pain and suffering. People leave religions all the time after contemplating the contradictions within them. This is all evidence of the fact that religions are full of myths and stories invented by changing humans. Imagining some perfect believer warmly ensconced in a perfect religion is imagining a profundity that isn't actually there. And wishing for such profundity is wishing for something that has so far not been available to us.

Secondly, Humanists don't have to see this as dispiriting. (Except that they literally de-spirit the world.) Many Humanists would say they are spiritually satisfied just fine thank you. Anyone who continues to go to Sunday Assembly meetings (founded by stand-up comedians and not affiliated with any Humanist organizations, by the way) may not find such meetings unappealing either, no matter how badly Morgan tries to caricature them. If it works for you, and it doesn't harm the world, then do it. That's the Humanist motto for finding your own profundity. And many of us do. (See, for example, my own version of meaning in life as being part of cosmic evolution, as discussed by the philosopher, and author of The Meaning of Life, John Messerly.)

Section §2.17 of the Humanist UK MOOC touches on this:

When it comes to so-called ‘ultimate’ questions about meanings and purposes, such questions are only important or meaningful if you believe such meanings and purposes really exist. For a Humanist, some of these questions can simply be dissolved.

Section §3.8 of the Humanist UK MOOC takes this further:

Humanists do not see that there is any obvious purpose to the universe, but that it is a natural phenomenon with no design behind it. Meaning is not something out there waiting to be discovered, but something that we create in our own lives. ... Every person will have many different meanings in their life. Each one of us is unique and our different personalities depend on a complex mixture of influences from our parents, our environment, and our connections.

For example, Morgan observes that we (social primates) have a desire for community, and that is right. Section §3.4 of the Humanist UK MOOC confirms this:

At the end of life people do reflect on what their contribution has been to society, to their family, and really start to try and think. ... Our connections between one another is one of the most potent things, and that is actually, for many of us who don't have a religion, really the most joyous and significant thing about life.

Section §3.17 of the Humanist UK MOOC (titled "Humanist Spirituality") addresses the question of profundity explicitly:

Critics claim that a humanist conception of a good life lacks a whole dimension, they say it leaves little room for depth or wonder. ... Many humanists argue that spirituality can be understood as referring to a set of natural human characteristics which are as vital to those who are not religious as to those who are. If we use the language of spirituality to refer to a natural dimension of human life, then non-religious people can be included in the discussion. ... Humanists believe that each of us constructs spiritual meaning for ourselves; we are responsible for our own spirituality. ... We feel a deep need to connect with something greater than ourselves. ... Non-religious people might equally connect with nature, the earth, or the universe; or with family, friends, or a political party; or with all of these, or something else. Humanists can achieve a sense of awe and wonder through the observations of science, which offer awe-inspiring insights into the natural world and the universe.

And in his exchange with Harari, Norman shows the truly profound inspirations and outcomes that have come from such a Humanist approach to living. He noted:

Progressive thinkers in the early twentieth century recognized the need for a broad social movement emphasizing human rights, reason, and freedom of inquiry. They admired all of the works you mention—those of Bacon, Locke, Hume, and Rousseau, the Declaration of Independence, and the Declaration of the Rights of Man. They also admired the works of Plato and Aristotle, Da Vinci and Spinoza, Kant and Paine, Bentham and Mill. They needed a word to designate central features of the philosophical orientation that had done so much to enlighten the world. For better or worse, they settled on humanism and began building a movement to spread these comparatively enlightened values. They authored the manifestos, pressed for a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, supported civil rights movements, and helped make women’s suffrage the rule rather than the exception. They helped inspire Gandhi’s efforts to throw off British colonial rule, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s efforts to end segregation. (King himself explicitly thanked the “thousands of humanists,” many of them white, who helped his civil rights movement.) Arguably, humanism’s emphasis on self-determination helped to dismantle European colonialism.

Profound indeed.

Critique 2 from Morgan / Tallis

2. Humanism has an unhealthy relationship with the sciences that serves to distort who we actually are.

As Tallis puts it early on in Seeing Ourselves: "Rejecting a supernatural account of humanity does not oblige us to embrace naturalism, as if this were the only alternative. It does not follow from the truth that we are not hand-made by God that we are simply organisms shaped by the forces of evolution; that, since we are not angels, we must be merely gifted chimps."

If the naturalist picture wishes us to endorse a seamless line from the Big Bang to Beyoncé (to use Michael Bavidge’s phrase), Tallis is keen to show that such a picture is implausible: “Evolutionary theory... cannot explain the emergence of consciousness out of insentience or the conscious subject out of sentience.” ... For Tallis, this is a “profound mystery” as the “machinery of the flesh, however exquisite, seems stony ground for the human subject.” ... For Tallis, we are neither natural nor supernatural, but extranatural.

It is important to note that naturalism is not an empirical scientific position so much as a philosophical position with clear epistemological and metaphysical theses:

- Epistemological: The standpoint and method(s) of the empirical sciences are the best way to acquire knowledge of every aspect of the world, including ourselves.

- Metaphysical: The world is comprised solely of the kinds of objects, properties and causal relations posited by scientific theories.

For Tallis, those in thrall to a naturalistic metaphysics fail to see ourselves, and thus diminish humanity

Response to Critique 2

The issue of scientism was covered above in the 4th dislike from Bavidge, but Morgan/Tallis are challenging the limits of science and the naturalist interpretation of what it has so far discovered. First of all, being a "gifted chimp" is no mere thing. We are amazing products of billions of years of genetic evolution, and tens of thousands of years of cultural evolution. Claiming anything beyond that natural history, however, relies on "a divine skyhook" as Dan Dennett would call it. Just because science has not YET explained the emergence of consciousness, does not mean that it cannot ever do so. Psychological studies of consciousness were verboten until the late 1980’s. Give it some time. See episodes 160-163 of the Brain Science Podcast for Ginger Campbell’s amazing four-part series on the latest books and findings from neuroscientists about studies of consciousness. I personally don't find it so mysterious anymore.

More broadly, sections §1.10 and §2.15 of the Humanist UK MOOC advise:

The history of science has taught us that in the absence of an existing scientific explanation we should be wary of turning to non-scientific or supernatural conclusions. ... The fact that science has solved so many of the mysteries of the past means we should be wary of leaping to supernatural explanations for things we do not currently understand. ... History has shown us that the rational position is to be patient, rather than to jump to non-scientific conclusions.

With his lack of patience, combined with a trepidation of announcing any supernatural beliefs, Tallis makes the move to call his idea extranatural, but according to the classical rules of logic this is an error that is literally nonsense as it refers to nothing. The law of the excluded middle says there is nothing between naturalism and supernaturalism. What Morgan calls "a hypothetically enriched naturalism" is either supernaturalism or just more naturalism.

As for Morgan's depiction of the epistemological and metaphysical stances of naturalism, this too is in error. In science, we deal with hypotheses, not theses. In fact, I call naturalism the first hypothesis, and, as yet, it has not been disproven. Thus, two important additions need to be added to Morgan's two points:

The empirical sciences are the best way….SO FAR...to acquire knowledge.

The world is comprised…AS FAR AS WE CAN TELL...solely of the kinds of [things] posited by scientific theories.

These are important caveats that naturalists are happy to hold and they make our position defensible. Thus, to claim that we are the ones who diminish humanity is backwards. Tallis is the one who doesn’t see us as enough, so he diminishes us by insisting there must be something else to explain us.

Critique 3 from Morgan / Tallis

3. Humanism is anti-Humanist

A consequence of the second critique is an ethical and political one, namely that the naturalistic tendency to show up central aspects of our subjective experience (e.g. consciousness, selfhood, free will etc.) as illusions is anti-humanist.

Tallis' focus is on grounding a future humanism in a particular attitude towards ourselves, one rooted in awe and celebration. Religion, after all, is not simply a response to human suffering but also a celebration of the greatness of God. Similarly, Tallis wishes us to focus on the greatness of the Human.

Tallis, in line with someone like Roger Scruton, is keen to emphasize incommensurability, e.g. humans and non-human animals are incommensurable.

Response to Critique 3

The naturalistic stance is not anti-Humanist, it is anti-angelic. Tallis' stance of worshiping humans is exactly what led to Bavidge's first dislike of some Humanists. However, as we saw above, the Humanist movement does not share these sacralizing views. It is not Humanism that is anti-Humanist, it is Tallis' views that are not in line with Humanism. Morgan's article ends by saying "Tallis is the best of the humanists, a thinker of undeniable profundity and sensitivity," but based on the definitions and analysis I've done here, the things that Morgan seems to admire about Tallis are actually the things that aren't Humanist.

As for the incommensurability between humans and non-human animals, the evolutionist in me asks....when did this split occur exactly? Are we modern people incommensurable with Homo habilis, erectus, neanderthalensis, or ancient Babylonians? No of course we aren't. Sorry, but there are no joints in nature. The differences we see between humans and non-human animals were built up over very long stretches of time by very small increments of cultural evolution, which were built on the back of even longer stretches of time for genetic evolution.

Critique 4 from Morgan

4. Humanism is uncomfortable with mystery.

The humanist belief that there are only problems, not mysteries, is well captured by the humanist Richard Dawkins who insists that we live in a universe in which “everything has an explanation”, and that if we have yet to discover one, then “we’re working on it”. Such is the expectant mastery of the contemporary humanist.

The Russian philosopher Leo Shestov contrasts two ways of doing philosophy, the first placatory, and the second – using Blaise Pascal as exemplar – inflammatory: "Philosophy sees the supreme good in a sleep which nothing can trouble... That is why it is so careful to get rid of the incomprehensible, the enigmatic, and the mysterious; and avoids so anxiously those questions to which it has already made answer. Pascal, on the other hand, sees in the inexplicable and incomprehensible nature of our surroundings the promise of a better existence, and every effort to reduce the unknown to the known seems to him blasphemy."

William James is very sympathetic to this kind of contrast, referring approvingly to how the latter inflammatory mode of thinking rebukes “a certain stagnancy and smugness in the manner in which the ordinary philistine feels his security.” In contrast to the placatory humanist orthodoxy, Tallis is consistently inflammatory, not just in his unsettling of the pretensions of materialism but in his willingness to acknowledge genuine mysteries that are in principle beyond the reach of the scientific worldview.

Response to Critique 4

This is profoundly wrong! Humanists are full of wonder and love to explore the mysteries of the universe as opposed to just saying “it’s God.” Humanists see that religions are the placatory philosophies: serve God; do as scripture says; all will be revealed and rewarded in heaven; sit in meditation until all desire is lost and nirvana is achieved. In contrast to this, Humanists are forever seeking and challenging knowledge. That is precisely why Humanism is not precisely defined and it continues to evolve. Humanists are very comfortable living lives without certainty. That is the definition of an inflammatory philosophy.

I would characterize Dawkins' position not as one of "expectant mastery," but as the logical conclusion of living in a causal universe, which so far has not shown us supernatural interventions. It’s not a "pretension of materialism" to hold onto this hypothesis until it is disproven. It is instead a pretension to insist on something else that hasn't been seen. There are many mysteries we may not now or ever master, but that doesn’t mean we ought to give up and worship them. Who knows? I may be surprised by what hard work and imagination may uncover someday about one or many of these mysteries. In contrast, Pascal's reticence to reduce the unknown to the known is mightily anti-Humanist. That is longing for the nasty, brutish, short, unenlightened “state of nature” that predated the sapiens of our species.

For more evidence of this, see sections §2.1 and §2.20 of the Humanist UK MOOC which say:

Socrates instructed us that ‘wisdom begins in wonder. If we are not prepared to consider the possibility that we might be wrong, then we are closing down the potential for, and the pleasures of, exploration, discovery, and progress. Humanists place great value on curiosity.

Humanists will recognize that science does not give us certainty. The truths of science are provisional. ... This means we can never be absolutely certain of anything. ... A consequence, then, of the humanist approach to knowledge is that humanists have to be prepared to live with uncertainty. To embrace the scientific method is to embrace skepticism and doubt. ... The belief that we can accept propositions of knowledge even though they cannot be proved with absolute certainty is called fallibilism. ... Uncertainty need not be something to be feared. The absence of certainty, and the recognition of our epistemic frailties, opens the door to one of life’s great pleasures...curiosity!

Critique 5 from Morgan / Tallis

5. Humanism cannot accept humans as they are, only as it would like them to be.

As a tough-minded humanist, Dennett sees his role as to persuade us to accept that which we don’t want—and to be grateful for it. ... It is all too easy for humanists to dismiss the desire for cosmic meaning as anything from “infantile” to “irrational” to “megalomaniacal” to “narcissistic” to “embarrassing” to “indefensible” etc., ... Yet the fact remains that such yearnings persist, and are rooted in basic facts about the kinds of beings we are. As Benatar puts it: “People, quite reasonably, want to matter. They do not want to be insignificant or pointless. Life is tough. It is full of striving and struggle; there is much suffering and then we die. It is entirely reasonable to want there to be some point to the entire saga.”

Tallis remains a humanist in the sense that he would not wish to frame deep forms of human yearning or longing for the absolute in supernatural terms: “The transcendence that enables humanity to live a life backlit by the supernatural is not at a distance from the human world and our humanity but within that world and within our humanity.” However, he parts from humanist orthodoxy in his recognition of the depths of such aspirations and the extent to which abandoning them would be experienced as a profound loss. For example, he raises the question of what humanism has yet to do “to fill the voids opened up in those who have lost their faith”.

Elsewhere, in a sentence that would surely horrify your average tough-minded humanist, Tallis writes that “we may need to learn how to reinsert our wishes into our thinking.” In this he mirrors Alexander Douglas’ questioning of the dominance of “hard-headed” naturalist philosophical attitudes: “Suppose a philosopher’s motivation in striving to glimpse an ultimate reality beyond appearance is to find comfort in the vision. I don’t see what’s so wrong with that.” Finally, Tallis notes that: “Lived meaning is not propositional,” which legitimizes the believer’s unwillingness to submit their belief to rational scrutiny of the kind favored by humanists.

Response to Critique 5

I feel sadness at all of the philosophical errors committed here, for they come from a place of expansive searching, rather than from any narrow-mindedness or dogmatic malice. However, it would be a naturalistic fallacy to accept humans only for what they have been. It would be illogical and anti-Humanist not to see the evidence that humans can and have changed for the better, that moral progress happens, and that we would do well to encourage more of that. Insisting that humans are a specific "kind of being" would be holding onto a Platonic essentialism that evolutionary history and modern psychology has shown us isn't there. Motivated reasoning is no reasoning at all. And an unwillingness to submit beliefs to rational scrutiny is the definition of an irrational and unexamined life.

In contrast to the position expressed here, Dan Dennett seems tender to me. He is not forcing us to accept dregs; he is helping us to accept that which we can’t have and to be amazed by what we do. The serenity prayer, for example, is not tough-minded. (Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.) Humans do want to matter. And we can. We can matter to all of the profound things discussed above. And we can get there by grappling with things like Abraham Maslow's humanist psychology (e.g. his pyramid of needs and later adaptations to it), or Irvin Yalom's existential psychology (e.g. his four ultimate concerns of life—death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness).

This is perhaps more difficult than Marx's opiates for the masses, but it works at least as well. Many, many Humanists left their religions with no exposure to Humanism at all. The religions just stopped making sense to them. Consigning oneself to the lack of any religious replacement would result in nihilistic atheism, but people rarely do this. They get on with their lives. And Humanism offers a positive vision of well-being that helps with this and is being extended all the time through additional rational research (e.g. the entire field of positive psychology).

Critique 6 from Morgan

6. Humanism is spiritually blinded by an excess of optimism.

The humanist sees any kind of pessimism as clear evidence of unruliness, a sure sign of intellectual weakness or resignation (“Pessimism is too easy...” muses an unborn baby in the humanist Ian McEwan’s novel Nutshell).

We are an aggressive, violent, anxiety-ridden, acquisitive, cruel, and lustful species. These destructive and self-destructive tendencies cohabit with ideals of fairness and fellow-feeling in the human psyche. Guilt is a deep part of the human personality. Many of us feel utterly condemned, bad beyond belief, fatally flawed at the centre of our personalities. Religion gives expression to these feelings of guilt (see, for example, Psalm 130); it expresses moral horror.

Cheerful Humanism, of the kind exemplified by a thinker even of Tallis’ undeniable depth, has no time for what Hume dismisses as “the monkish virtues”: repentance, contrition, the ascetic life etc. It sees them as pathological, backward-looking obstacles to personal and social progress. ... Humanists are consistently guilty of responding dismissively – and even callously – to what Benatar has called “the reasonable sensitivities of the pessimists”. Humanism, as a cheerful voice of reason, progress, and optimism simply lacks the resources to make sense of this darker side of human life.

Response to Critique 6

This critique evokes more sadness (and perhaps a recommendation for Maybe You Should Talk to Someone by Lori Gottlieb, who is another fan of Irvin Yalom). Regardless of whether these feelings of darkness were personal or hypothetical, however, they are easily addressed with Humanist resources. We humans have evolved a wide range of plasticity in our actions that enable us to respond effectively to all sorts of environments. The negative traits that Morgan listed are actually helpful in some instances. Feelings of guilt and remorse over previous actions are precisely there to help motivate us to change for the better. The "monkish virtues" can absolutely be virtuous, but all things in moderation. Humanist psychologists would see wallowing in them as dysfunctional, but their mere existence is perfectly normal. It would, instead, be wrongfully essentialist to claim utter condemnation for a person and ignore the role that growth and adaptation can play within one lifetime. Religion is wrong (and anti-Humanist) to give expression to such condemnations. They are founded on the view of an eternal unchanging soul, but we do not appear to be made of such stuff.

If Humanists were truly blind to the darker side of humanity, they would do nothing to improve things. That is demonstrably false, however. The North East Humanists have raised over £25,000 in the last five years for charitable organizations that help the less fortunate. Pessimists don’t insist the world remain bad; they see the bad clearly in order to improve it. And Humanists clearly do this too. If anything, cheerful, blissful monkish types removed from society are much more dismissive and callous.

For more evidence of this, section §5.16 of the Humanist UK MOOC also makes this plain:

Humanists view practical action as important in order to give everybody the opportunity to live lives that are well lived, enjoyable, and happy. ... Humanists UK, in its campaigning work, tends to focus on issues where there is disagreement between Humanists and non-religious people, and the position taken by many religious groups. ... Faith without works is not Christianity, and unbelief without any effort to help shoulder the consequences for humankind is not Humanism.

***

So as we can see, Humanism has developed a full and robust set of ideas behind it, and it is always continuing to work on them. The lists of questions, dislikes, and critiques of Humanism from its potential allies above have all been able to be answered. The fact that it takes much work to do so is perhaps a fault of the non-evangelical side of Humanism, but it is also down to the fact that Humanism is a kind of thing perhaps not seen in the world before. As I said above, Humanism isn't an "ultimate philosophy" providing ultimate answers for all its devotees. Humanism is more of a big tent movement asking for broad agreement about the rational limits of trial and error that we should be exposing ourselves to as we try to make sense of this knowable, yet perhaps forever mysterious, existence we find ourselves in.

With that, I'll end with a plea to join this big movement. If you've read this far and aren't yet a member of a Humanist organization, please consider it. We need all the help we can get, and your small contributions enable a lot of great things to happen. In a recent brochure I produced for the North East Humanists, I noted the benefits that membership at the local or national level provide. They are:

| Local NEH membership supports:

Join North East Humanists Today Memberships start at just £6 per year | National HUK (or AHA) membership supports:

Join Humanists UK Today Memberships start at £48 per year Join American Humanist Association Today Memberships start at just $1 per year |