BBC: Richard, can you read us a passage from the beginning of your book to get us started?

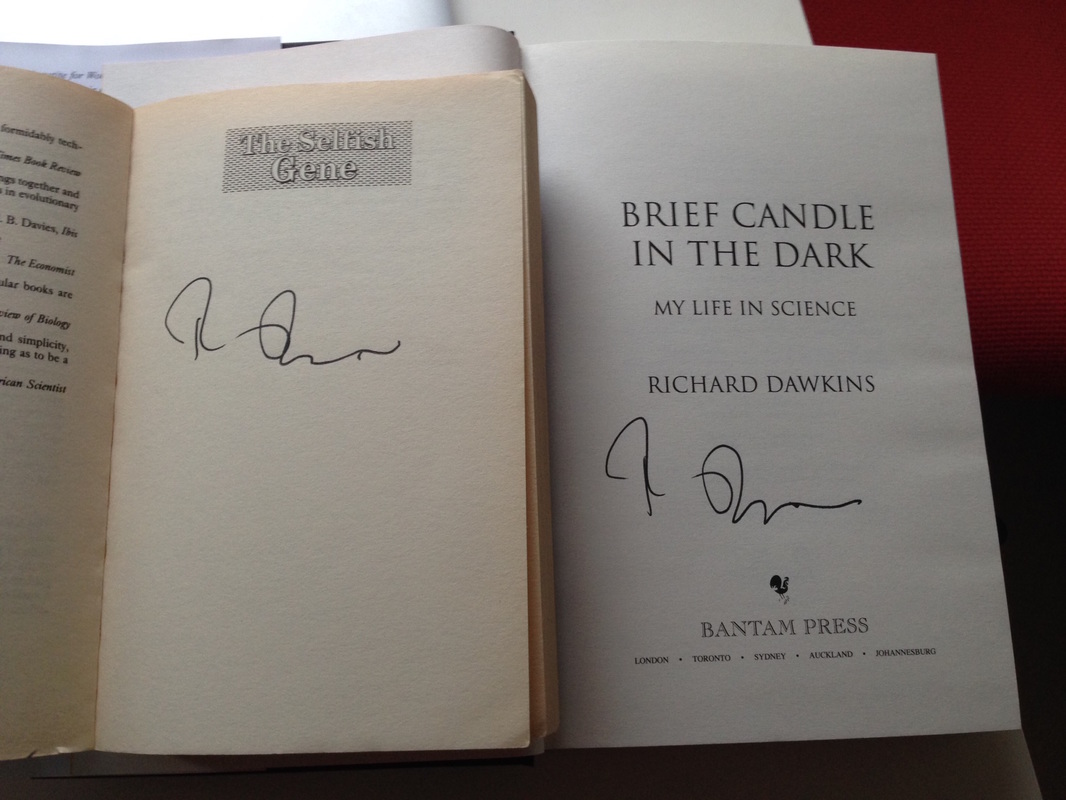

RD: (reading) What am I doing here, in New College Hall, about to read my poem to a hundred dinner guests? How did I get here - a subjective 25-year-old, objectively bewildered to find himself celebrating his 70th circuit of the sun? Looking around the long, candlelit table with its polished silver and sparkling wineglasses, reflecting flashes of wit and sparkling sentences, I indulge my mind in a series of quick-firing flashbacks. Back to childhood in colonial Africa amid big, lazy butterflies; the peppery taste of nasturtium leaves stolen from the lost Lilongwe garden; the taste of mango, more than sweet, spiced by a whiff of turpentine and sulphur; boarding school in the pine-scented Vumba mountains of Zimbabwe, and then, back 'home' in England, beneath the heavenward spires of Salisbury and Oundle; undergraduate days damsel-dreaming among Oxford's punts and spires, and the dawning of an interest in science and the deep philosophical questions which only science can answer; early forays into research and teaching at Oxford and Berkeley; the return to Oxford as an eager young lecturer; more research (mostly collaborating with my first wife Marian, whom I can see at the table near here), and then my first book, The Selfish Gene. Those swift memories take me to the age of thirty-five, halfway to today's landmark birthday. They milestone the years covered by my first book of memoirs, An Appetite for Wonder.

BBC: We all start somewhere and end somewhere. Your journey was a very long one. Looking back, does it make sense? Or does it feel like something strange and rather unlikely?

RD: (laughs) It feels pretty strange.

BBC: As I read this book, I was aware of your Englishness. You grew up in colonial Africa, were raised in the Anglican church, spent a lot of time at Oxford, love English poetry, and cricket. You are profoundly English.

RD: I fear I am.

BBC: There's a real sense of melancholia in the title of this memoir: Brief Candle in the Dark.

RD: Well the title is a combination of two things. Brief candle comes from Macbeth: "Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more." That part is melancholy. But the second half of the title comes from Carl Sagan's book The Demon Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, which is a marvellous book. So there's an uplift at the end of the title.

BBC: You became very famous writing about the selfish gene, which takes the stance that our bodies are very provisional. You were even quite poetical about this.

RD: Yes, I call them survival machines. I even wrote a little poem about it. I think it goes something like this:

An itinerant selfish gene,

Said bodies aplenty I've seen

You think you're so clever

But I'll live forever

You're Just a survival machine

(applause)

And then I also wrote the body's reply as a parody of Kipling:

What is a body that first you take her

Grow her up and then forsake her

To go with the old blind watchmaker

BBC: You're a melancholy, late-19th century englishman. (laughter)

RD: I'm actually quite cheerful. (big laughter) And Brief Candle in the Dark is not a melancholy book. I think it's actually a funny book. Though I was invited to a symposium titled Poetry that Makes a Grown Man Cry and I read something by A.E. Housman who is very melancholy. Did you know he never went to Shropshire?

BBC: You were part of a movement of behavioural evolutionists, that was very important. What did that feel like?

RD: I thought I was merely portraying neo-darwinism that had arrived in 1930's, but in a new way. I didn't realise it would be so controversial, but it was. I was 35 or so though and was up for that fight.

BBC: Science is a collaborative field, much more so than the humanities. But as you became famous you've had to pull into more solitary efforts. Would you have liked to have been more collaborative?

RD: I would have. But it just didn't work out, and I don't plan my life. I've just drifted. It was luck that I fell into biology and then I was lucky to get into an important animal behaviour group. I almost became a biochemist, which would have changed everything.

BBC: Do you really drift?

RD: I don't plan. I don't, for example, know the next book I'm writing but one. They just sort of arrive and then I write them.

BBC: In the part of your life covered by this book, you've become much more of a celebrity. How have you handled that? I'm a Methodist and my view of Anglicans is that they are not very self-reflective.

RD: I'm not really an Anglican. (laughter)

BBC: I know that, but you were brought up as one, and it's left its mark on you. I'm interested in the way the celebrity has allowed you to forsake your inner self and look outwards more.

RD: I'm not really a celebrity. I don't get recognised in the street. But it is vaguely irritating that I can't make a casual remark without it being picked up in the papers and blown out of proportion. It's an irritation though, not a great pain.

BBC: If you were in the humanities, you would certainly by now be a Sir. Does that tell us something about our culture that scientists are less likely to be knighted?

RD: My lips are sealed. (laughter)

Audience: (referencing his intro) What are the deep philosophical things that science can answer?

RD: The meaning of life. How did it all start. Why are we here. What is life.

BBC: And the things that science can't answer?

RD: What is right and what is wrong. (My note: I obviously don't think this is true anymore, but I haven't been able to get in touch with Dawkins to talk to him about this.)

Audience (a child of about 10): Are religious blokes crazy or are they just brought up like that?

RD: Oh gosh, what can I say? Brought up that way. The great majority of people have the same religion as their parents, and that really gives the game away. The fact that children inherit the religion of their parents and the fact that we as a society label them as such is what drives this. We call a child of two a Catholic child, as if they had the faintest idea of what that means. A midwife will hold a newborn baby up and ask, "What religion is he?" It's shocking if you think about it. It's just as absurd as asking, "Is he a logical positivist? Is he an existentialist? Is he a Marxist?"

BBC: Did Oxford prepare you to be such a controversialist?

RD: There's nothing controversial about what I just said. (laughter)

BBC: I mean generally, did Oxford prepare you?

RD: Any university ought to prepare you to value truth, and to want to speak truth, and to want to stick up for it. Not in a belligerent way, but in a clear and unambiguous way.

BBC: Most academics don't do what you do.

RD: True, but that's because they're too busy doing other things. After 35 I stopped devoting my spare time to laboratory research, so I've had more time to do what I think other people in university ought to do more of.

BBC: You've turned outwards. What made you different than your colleagues?

RD: I don't think I'm that different. Oxford and others have long traditions of looking outward.

BBC: But the people who do so are largely the exception.

RD: Okay, but there is a large minority of exceptions.

BBC: You're wonderfully refusing to look inwards, but there must be a reason you've become one of those exceptions.

RD: I am passionate about truth. I am passionate about clarity. I despise wanton obscurantism. I often find myself bewildered. I struggle to understand, but once I do understand, I want to help others understand. There's a cartoon I've seen which could be me, where a husband is telling his wife, "I can't come to bed. Someone's made a mistake on the internet!"

BBC: At what point did you decide to turn your fire against religion?

RD: I think I've always had to because my subject of evolution is in the front line. The last chapter of The Selfish Gene referred to religion as "viruses of the mind."

BBC: What triggered that? Arguing with your own bringing up?

RD: Not at all. Certainly not by anything from my parents. Maybe from Chrisitan schools though. I refused, with a few friends, to kneel down in chapel once, but the school was okay with that. There were none of the horror stories you hear from Catholics or other religions.

BBC: Do you regret giving up laboratory work to do television and media about these things?

RD: Not really. I don't think I was particularly good at it so I'm probably better employed doing what I have been doing.

Audience: You've been talking about religion for a long time now. What changes in society have you observed in regards to religion during your time talking about it?

RD: There's been a steady downtrend in opinion polls. Even Americans have 20% of the population now who profess no religion. A charity of mine, the Richard Dawkins Foundation, is doing research about this and drawing attention to this. Non-believers now outnumber any one religion in America. In Britain, the foundation did an interesting survey. The 2001 census here reported 73% people labeled themselves as Christian. The 2011 census reported only 54%. That's great, but we were even skeptical of that. So we commissioned an opinion poll to be done the same week of the census to ask people who identified as "Christian" a bunch of supplementary questions to see just how Christian they really were. Do you believe Jesus is your lord and saviour? Do you believe Jesus was born of a virgin? Do you believe Jesus rose from the dead? The number of people who responded yes to these dropped dramatically. Name the first book of the new testament, out of the following four: Matthew, Acts, Psalms, or Genesis. Only 37% of the people who call themselves Christians were able to pick Matthew out of that list. Why did you tick Chrisitan? The greatest answer by far was 'because I like to think of myself as a good person'. When faced with a moral dilemma, what do you appeal to? Only 10% appealed to their religion when making a moral decision. The number of Christians is actually far lower than the census reports.

BBC: Did you cause this?

RD: Oh no. My foundation gets letters from people who say I've helped change their lives about religion, but I've certainly got no real data on this. Sadly, I fear some people are leaving religion but picking up other irrational thinking.

Audience: (long rambling question about truths and religious truths)

RD: I have to say Brief Candle in the Dark is not about religion. (laughter) We're getting a lot of questions about religion, which this has nothing to do with.

(Audience member off-mike: But that's what we're interested in!)

RD: Well then read The God Delusion. This book is a reflective, humorous, affectionate, gentle book. I just want to get that out there. (laughter)

Audience: (Another long question about dismissing religion...)

RD: I don't want to dismiss it. I'm happy to discuss it, though maybe not now while we're in front of a large audience. But I value evidence. In terms of your own beliefs, I would want to know what supernatural beliefs you have and what evidence you think you have for those.

BBC: You say science wasn't your greatest métier. But you're a very interesting writer, literary even. How much is writing now your primary skill?

RD: I suppose it is. I love language, the sound of it, hearing it read aloud, the cadence, poetry, prose that verges on poetry.

BBC: In soundcheck, we asked you the boring question "What did you have for breakfast?" You quoted a passage from victorian literature. Can you give us a moment from that?

RD: Oh it's not worth it! (laughter)

BBC: Yes it is actually!

RD: Well okay.

(reciting very quickly) So she went into the garden to pick a cabbage leaf to make an apple pie. And passing through the street, the great she-bear popped it's head into the shop window. What no soap? So he died. And she very imprudently married the barber. (laughter)

BBC: You love clarity, but some poetry gives you nonsense, deliberately gives you nonsense. Keats, who you love, doesn't give you clarity, nothing like the evidence-based clarity from your scientific work.

RD: It's funny you should mention Keats. Unweaving the Rainbow comes from Keats' criticism of Newton who he says has spoiled the poetry of the rainbow.

BBC: What does poetry give you?

RD: Well, my favourite poet is Y.B. Yeats who was a rampant mystic. But something about his language just bores into my brain.

BBC: So the man who likes reason and clarity likes Yeats? There's something odd about you.

RD: No, I'm just complex! (laughter)

BBC: There must be something in poetry that gives you what science doesn't.

RD: It's the language, the imagery, the rhythm. It's like music for me.

BBC: Never the content?

RD: No, sometimes the content, like Shakespeare.

BBC: And how does the scientist deal with the content of "And the rain that raineth every day and a hey ho and the wind and the rain," as said by Shakespeare at the end of the Twelfth Night?

RD: The rain that raineth. Ah the rain that raineth actually comes from the Bible of course. "The rain that raineth every day upon the just and the unjust." There's a lovely, I think, Victorian rhyme that goes:

The rain that raineth every day, upon the just and the unjust fella.

But more upon the just because the unjust hath the just's umbrella.

(big laughter)

BBC: The Bible. Poetry. Literature. You're always tough on religionists, although you're a gentle, kind man, and my experience with you says this is so. But you're drawn to a use of language, to content, to melancholia, and mysticism of poets that speaks to a part of you that largely you hide from the public.

RD: I don't hide it. The poetry's there in all the books. I can't explain the Yeats thing.

BBC: Yeats is a great poet of older age. He has an acute sense, as you do, of the body being here but passing away. Is it that that draws you, because...?

RD: No I don't think so. (laughter)

BBC: (shrugs, and moves on) If we could conjure up your mother and father, what would your parents say of their son's fame?

RD: Well my mother's about to celebrate her 99th birthday so we could ask her. (laughter)

BBC: What *does* she say?

RD: She says things like, "You're being interviewed in Newcastle? What do they want to interview you for? (laughter)

BBC: And your father?

RD: I think he was quite pleased.

BBC: I love "quite pleased." If we go back to England and Englishness, "quite pleased" is a very good way of ending.

-----------------------------------------

As a brief postscript, I really enjoyed hearing Dawkins speak, and this was by far the softest, kindest Dawkins I've heard. Perhaps only the confrontational Dawkins came out in the past because he had written confrontational books and was forced to discuss and defend them. But now that it's time to just tell his life's story, his much softer side comes through. His wit and recall about poetry, the Bible, Shakespeare, and even silly old rhymes was extraordinary. He seems to genuinely believe that he really isn't any different than most of his colleagues in terms of speaking out on behalf of science, but I have to think his passion for literature is what made him the great communicator that he is, and that is why he *has* stood out from everyone else. He is a shining example of the need for a well-rounded education in us all and I'm inspired to continue my own efforts towards that. Hopefully I've now helped him reach a few more people with this message too.