David Hume introduced this experiment during his effort to fully describe the features of Empiricism. From my Philosophy 101 page:

Empiricism - is a theory of knowledge that asserts that knowledge comes only or primarily via sensory experience. Empiricism emphasizes evidence, especially as discovered in experiments. It is a fundamental part of the scientific method that all hypotheses and theories must be tested against observations of the natural world rather than resting solely on a priori reasoning, intuition, or revelation.

With that in mind—especially the part about knowledge coming only via sensory experience—let's look at the particulars of this week's experiment.

---------------------------------------------------

Imagine living your whole life in a complex of apartments, shops, and offices with no access to the outdoors. That pretty much sums up life for inhabitants of the massive space stations Muddy and Waters.

The creators of the stations had introduced some interesting design features in order to test our dependence on experience for learning. On Muddy, they ensured that there was nothing sky-blue on the whole of the ship; on Waters, there was nothing blue at all. Even the inhabitants were chosen so that none carried the recessive gene responsible for blue eyes. To avoid anything blue being seen (such as veins) the lighting in the station was such that blue was never reflected, so veins actually appeared black.

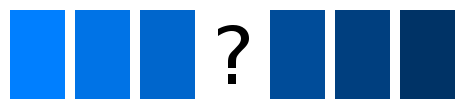

When those born on the stations reached eighteen, they would be tested. Those on Muddy would be shown a chart with all the shades of blue, with sky-blue missing. The subjects would be asked if they could imagine what the missing shade looked like. They would then be shown a sample of the color and asked if this is what they had imagined.

Those on Waters would be asked if they could imagine a new color, and then if they could imagine what color needs to be added to yellow to produce green. They too would then be shown a sample and asked if they had imagined that. The results would be intriguing...

Source: Book two of An Essay (sic) Concerning Human Understanding by David Hume (1748)

Baggini, J., The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten, 2005, p. 121.

---------------------------------------------------

It's funny that Baggini (or his publishers) made a mistake in the source reference here, citing the title of John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding when wikipedia explicitly points out that "it should not to be confused with" David Hume's Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, but nonetheless Baggini adds an intriguing step to the original experiment, which I'll get to a bit later. First, I must tackle what Hume wrote, which has come to be known as The Missing Shade of Blue. He argued "that all perceptions of the mind can be classed as either 'Impressions' or 'Ideas'. He further argues that:

"We shall always find, that every idea which we examine is copied from a similar impression. Those who would assert, that this position is not universally true nor without exception, have only one, and at that an easy method of refuting it; by producing that idea, which, in their opinion, is not derived from this source."

Just two paragraphs later though, Hume seems to provide just such a destructive idea that arises without a sense impression. He says:

"There is, however, one contradictory phenomenon, which may prove, that it is not absolutely impossible for ideas to arise, independent of their correspondent impressions. I believe it will readily be allowed that the several distinct ideas of colour, which enter by the eye...are really different from each other; though, at the same time, resembling. Now if this be true of different colours, it must be no less so of the different shades of the same colour; and each shade produces a distinct idea, independent of the rest. ... Suppose, therefore, a person to have enjoyed his sight for thirty years, and to have become perfectly acquainted with colours of all kinds, except one particular shade of blue, for instance, which it never has been his fortune to meet with. Let all the different shades of that colour, except that single one, be placed before him, descending gradually from the deepest to the lightest; it is plain, that he will perceive a blank, where that shade is wanting, and will be sensible, that there is a greater distance in that place between the contiguous colours than in any other. Now I ask, whether it be possible for him, from his own imagination, to supply this deficiency, and raise up to himself the idea of that particular shade, though it had never been conveyed to him by his senses? I believe there are few but will be of opinion that he can: And this may serve as a proof, that the simple ideas are not always, in every instance, derived from the correspondent impressions; though this instance is so singular, that it is scarcely worth our observing, and does not merit, that for it alone we should alter our general maxim."

Surprisingly, this has remained a stubborn problem. On wikipedia, there are currently six ways listed that people have attempted to deal with it, all of which suffer from problems.

- There is no problem - Hume was wrong when he claimed that it was possible to form an idea of the missing shade. (This is clearly wrong as new shades can be imagined and invented all the time. Think of recent introductions of high-viz products.)

- Mental mixing - just as paint cans can be mixed in a store, our brain can mix the idea of colours. (This is clearly wrong as we can't deduce things like blue + yellow = green.)

- Colours as complex ideas - colours are already mixed up so we can imagine their components like we can imagine the different properties of an apple = crunchy + juicy + red + sweet, etc. (This is mostly wrong as you can't deduce yellow = green - blue.)

- It doesn't undermine Hume's main concern - he doesn't claim to be perfect, but his principles are still useful for metaphysical debates. (This is clearly wrong as Hume himself states that any single instance of an idea from outside a sense impression would admit dualism, rationalism, or idealism into any argument.)

- The exception really is singular - colours and their shades can be organised together in a way that other things can't be. (This is also wrong because any singular example can be extended to others, which collectively undermine the general claim that ideas depend on impressions.)

- Hume needs an exception - he later makes larger claims that empirical discoveries are only ever probable so he must have found it good to find possible exceptions that prove we aren't certain. (This is nonsense as this particular possibility—imagining things with no basis for getting there—would destroy all the rest of his assumptions.)

As the conclusion to the wikipedia entry states, "None of the suggested solutions are without difficulty." You don't say! Even Massimo Pigliucci tried to tackle this a few years ago in a blog post and just ended up saying Hume found a "hypothetical" hole in his argument. Big deal. Pragmatically it doesn't matter so "philosophers should just relax about it." What an embarrassment! Hume had no access to modern scientific knowledge so he can be forgiven, but Pigliucci, who has PhD's in philosophy AND biology, should have seen right through all this. For us to do so, we'll need a brief detour into the way our eyes function and see colour.

Over on science presenter Steve Mould's blog, he made a really nice post about our eyes that tells us what we need to know, so I'll just quote that at length:

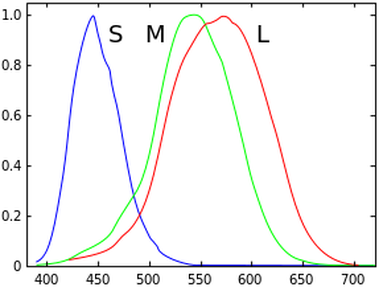

"At the back of our eyes there are little cones that collect light. When light falls on one of these cones it sends a message to the brain to let it know. The more light that falls, the stronger the signal that is sent to the brain. But what about colour? It turns out that there are three types of cone that correspond to red, green and blue. So if you're looking at something blue, it's the blue-sensitive cones that react and tell the brain there's something blue out there and so on. What happens when you look at something yellow? Yellow is inbetween red and green on the spectrum. Because it's not quite red and not quite green it excites both the red-sensitive cones and green-sensitive cones but only a bit! The brain gets a signal from both cones and deduces that it must be looking at something in the middle. Something yellow! Correct."

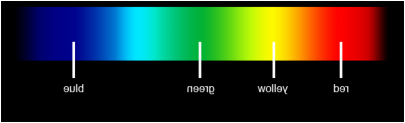

A couple of pictures help add some clarity to this. Here is a picture of the colour spectrum flipped around to (sort of) line up with a chart of the overlapping spectral sensitivities of our three cones as plotted against wavelengths of light:

This answers Hume's missing shade of blue, and it answers Baggini's experiment on the space station Muddy where only sky-blue was missing. But what about on Waters where no blue has ever been seen?

This is akin to Mary's Knowledge Problem, which I answered in my reply to thought experiment 13. In that thought experiment, Mary "knows everything" there is to know about red but has never seen red. Once she does, she learns something new, which supposedly shows there must be something beyond the physical world. As I said, this is hogwash "because Mary does not have 'all the physical information' and cannot know 'all there is to know' about this subject without having experienced it firsthand. Why? Precisely because we live in a physical universe where mental imaginings are not enough to move the physical atoms that make up the nerves in our eyes and the synapses in our brains. In philosophical terms, there is a real epistemic barrier to what we can learn no matter how much we sit in our rooms and read and think."

Looking at the colour charts above, we see that in Mary's case, her red cone has never fired so she cannot imagine what that sense organ feels like. On the spaceship Waters, it would be the blue cone that had never fired. This is a difference in kind, rather than a difference in degree, as compared to the case of the missing shade of blue. Mary, or the people on Waters, would feel the same impotence as we do when we try to imagine what birds can see with their fourth cone, which enables them to see ultraviolet light and magnetic fields. (How cool is bird vision!)

That would seem to be that, but In Baggini's writeup to this thought experiment, he raised another intriguing question that is worth examining. He said:

"Even if those born on Waters could imagine blue, that still leaves one question unanswered. Can they do this because, as humans, they are born with some kind of innate sensitivity to blue, or could they imagine any colour?"

As I said, the fact that their blue cones have never been activated would leave the people on Waters unable to imagine blue, but in Richard Dawkins' latest memoir Brief Candle in the Dark, he made an interesting point about our innate sensitivity to things, which, even if unfelt to date, could be discovered to exist, but only for colours our ancestors have experienced (barring the existence of a recent or dormant mutation). He said:

"There is a sense in which the DNA of a species could, in principle, be read out as a kind of description of the way of life at which the species excels. I have mentioned this idea of 'the Genetic Book of the Dead' in several of my book, but I argued it most fully in the chapter of that name in Unweaving the Rainbow. Here's one of the ways I introduced it:

' ... If you find an animal's body, a new species previously unknown to science, a knowledgeable zoologist allowed to examine and dissect its every detail should be able to 'read' its body and tell you what kind of environment its ancestors inhabited: desert, rain forest, arctic tundra, temperate woodland, or coral reef. The zoologist should be able to tell you, by reading its teeth and guts, what it fed on. Flat, millstone teeth and long intestines with complicated blind alleys indicate it was a herbivore; sharp, shearing teeth and short, uncomplicated guts indicate a carnivore. The animal's feet, and its eyes and other sense organs spell out the way it moved and how it found its food. Its stripes or flashes, its horns, antlers, or crests provide a readout, for the knowledgable, of its social and sex life." (my emphasis added)

Fascinating. And with that, I'll finish up with a short video of another fascinating colour fact I learned about while writing this. It's about the curious case of magenta. That's a colour that is not found in the visible spectrum of light, yet we all see it, and it's actually rather common in nature. Intrigued? Watch this 5-minute video from the Royal Institute.

It's always surprising to me to find philosophical problems like this that haven't been solved yet when it seems they easily could have been with the benefits of an evolutionary science perspective. But maybe that's to be expected from thinkers who haven't had the right parts of their brain tickled yet. Next!